In Current Debates About Regional Australia, Many Observers Point to A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1)

Australian Capital Territory Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Disallowable instrument DI2013-228 made under the Public Place Names Act 1989 — section 3 (Minister to determine names) I DETERMINE the names of the public places that are Territory land as specified in the attached schedule and as indicated on the associated plan. Ben Ponton Delegate of the Minister 04 September 2013 Page 1 of 7 Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au SCHEDULE Public Place Names (Lawson) Determination 2013 (No 1) Division of Lawson: Henry Lawson’s Australia NAME ORIGIN SIGNIFICANCE Bellbird Loop Crested Bellbird ‘Bellbird’ is a name given in Australia to two endemic (Oreoica gutturalis) species of birds, the Crested Bellbird and the Bell-Miner. The distinctive call of the birds suggests Bell- Miner the chiming of a bell. Henry Kendall’s poem Bell Birds (Manorina was first published in Leaves from Australian Forests in melanophrys) 1869: And, softer than slumber, and sweeter than singing, The notes of the bell-birds are running and ringing. The silver-voiced bell-birds, the darlings of day-time! They sing in September their songs of the May-time; Billabong Street Word A ‘billabong’ is a pool or lagoon left behind in a river or in a branch of a river when the water flow ceases. The Billabong word is believed to have derived from the Indigenous Wiradjuri language from south-western New South Wales. The word occurs frequently in Australian folk songs, ballads, poetry and fiction. -

Whatever Season Reigns

Whatever Season Reigns... Reflection Statement 24 Whatever Season Reigns... 25 In primary school I discovered “Land of the Rainbow Gold”, a collection of Classic Australian Bush Poetry compiled by Mildred M Fowler. As a child growing up in the homogenised landscape of suburban Australia I was captured by the romantic notion of Australia’s bush heritage. It was a national identity seeded in our rural beginnings; and much like Banjo Patterson wistful musings I always rather fancied I’d like to “change with Clancy, like to take a turn at droving where the seasons come and go”1; Many seasons later I returned to these poems for inspiration for my major work “Whatever Season Reigns...”2 On revisiting the works of writers such as Paterson and Lawson I was struck with how little I actually shared with these voices that were deemed to have forged Australia’s “literary legend” and our national identity3. The Australian narrative was one shaped by male experiences. There was no room for women. Only the token “drovers wife”4 or “army lass”5 proved anomalous to the trend but were not afforded the same complexity as their male counterparts. According to Kijas “Despite their invisibility in much nationalist and historical narrative, women in their diversity have been active historical protagonists across outback landscapes.” 6My work, appropriating the short 1 Paterson, AB. “Clancy of The Overflow.” Land Of The Rainbow Gold. Ed. Fowler, Mildred M. Melbourne: Thomas Nelson, 1967. Print. 2 Moore, JS. (1864) Spring Life - Lyrics. Sydney: Reading and Wellbank. 3 Simon, C. (2014). Banjo Paterson: is he still the bard of the bush?. -

Henry Lawson and the Salvation Army – Stuart Devenish

Vol. 2 No. 1 (November 2009) Henry Lawson and the Salvation Army – Stuart Devenish. On February 19, 2009 Salvation Army Major Bob Broadbere (retired) presented a lecture entitled 'Henry Lawson and his place in Salvation Army History' to an audience of approximately 70 people, mainly Salvation Army officers and soldiers at the Salvation Army’s Booth College campus at Bexley North, Sydney. The connection between Lawson and the Salvation Army has held an enduring fascination for Broadbere who has amassed a comprehensive personal library on Henry Lawson and his association with the Salvation Army. Having corresponded with the late Prof. Colin Roderick (editor of the 3 volume Henry Lawson, Collected Verse, A & R, Sydney, 1966-8) Broadbere is something of a specialist in the field. His interest in Henry Lawson sprang to life when Broadbere himself lived and worked in the St Leonards-North Sydney areas where Lawson had lived. Permission was obtained from Major Bob Broadbere to reproduce here some of his research as presented in his lecture. The ‘Army’ in Lawson’s Poetry The connection between Henry Lawson and the Salvation Army remains largely unknown in any of the contexts relevant to it, e.g., the Salvation Army, the Christian community, or the wider Australian population. In part this is because writers such as Banjo Paterson and Henry Lawson are not so well known nor so carefully read as they once were. Our understanding of the connection between Lawson and the Salvation Army is not helped by the oblique nature of Lawson’s writing about the Army. According to private correspondence between Roderick and Broadbere, Lawson never threw himself on the mercies of the Army despite his alcoholism and illness later in life. -

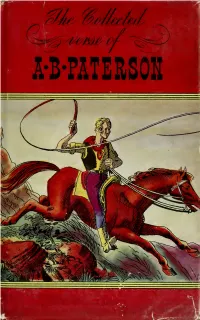

The Collected Verse of A.B. Paterson : Containing the Man from Snowy

The Collected Verse of A.B. ^^ Banjo^^ Paterson First published in 1921, The Collected Verse of A. B. Paterson has won and held a large and varied audience. Since the appearance of The Man from Snoiuy River in 1895, bushman and city dweller alike have made immediate response to the swinging rhythms of these inimitable tales in verse, tales that reflect the essential Australia. The bush ballad, brought to its perfection by Paterson, is the most characteristic feature of Australian literature. Even Gordon produced no better racing verse than "The Ama- teur Rider"' and "Old Pardon, the Son of Reprieve"; nor has the humour of "A Bush Christening" or "The Man from Ironbark" yet been out- shone. With their simplicity of form and flowing movement, their adventu- rous sparkle and careless vigour, Paterson's ballads stand for some- thing authentic and infinitely preci- ous in the Australian tradition. They stand for a cheerful and carefree attitude, a courageous sincerity that apart from is all too rare today. And, the humour and lifelikeness and ex- citement of his verse, Paterson sees kRNS and feels the beauty of the Australian landscape and interprets it so sponta- neously that no effort of art is ap- parent. In this he is the poet as well as the story-teller in verse. With their tales of bush life and adventure, their humour and irony "Banjo" Paterson's ballads are as fresh today as they ever were. (CoiUinued on back flap) "^il^ \v> C/H-tAM ) l/^c^ TUFTS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES nil 3 9090 014 556 118 THE COLLECTED VERSE of A. -

'Banjo' Paterson and an Irish Racing Connection

Australia’s Bard, ‘Banjo’ Paterson and an Irish Racing Connection By James Robinson M. Phil. Andrew Barton Paterson, through his writings, has come to symbolize the Australian outback. His poetry, ballads and novels reflect the spirit of rural Australia. The vast distances, the harsh climate and the beauty of the landscape are the background to his stories, which invariably reference horses. Paterson’s characters never give in, but endure with stoic determination and laconic humour to survive and often succeed. Banjo Paterson loved horses and horseracing and was himself an accomplished horseman and student of horse breeding. His best known works include ‘The Man from Snowy River’, ‘Clancy of the Overflow’ and inevitably ‘Waltzing Matilda’. The latter is known worldwide as the unofficial anthem of Australia. This paper references his life and times and an Irish racing connection - The Kennedys of Bishopscourt, Kill, Co. Kildare. Born on February 17 1864 at Narrambla, near Orange, New South Wales, A. B. Paterson was the eldest of seven children born to Andrew Bogle Paterson (1833-1889), a Scottish migrant who married Rose Isabella Barton (1844-1903), a native born Australian. ‘Barty’, as he was known to family and friends, enjoyed a bush upbringing. When he was seven, the family moved to Illalong in the Lachlan district. There, the family took over a farm on the death of his uncle, John Paterson, who had married his mother’s sister, Emily Susanna Barton. Here, near the main route between Sydney and Melbourne, the young Paterson saw the kaleidoscope of busy rural life. Coaches, drovers, gold escorts and bullock teams together with picnic race meetings and polo matches were experiences which formed the basis for his famous ballads. -

Saltbush Bill, JP, and Other Verses</H1>

Saltbush Bill, J.P., and Other Verses Saltbush Bill, J.P., and Other Verses Saltbush Bill, J.P., and Other Verses By A. B. Paterson [Andrew Barton ("Banjo") Paterson, Australian poet & journalist. 1864-1941.] [Note on text: Italicized lines and stanzas are marked by tildes (~). Italicized words or phrases are CAPITALISED. Lines longer than 78 characters are broken and the continuation is indented two spaces. Some obvious errors have been corrected (see Notes).] Saltbush Bill, J.P., and Other Verses By A. B. Paterson Author of "The Man from Snowy River, and Other Verses", "Rio Grande, and Other Verses", and "An Outback Marriage". Note page 1 / 122 Major A. B. Paterson has been on active service in Egypt for the past eighteen months. The publishers feel it incumbent on them to say that only a few of the pieces in this volume have been seen by him in proof; and that he is not responsible for the selection, the arrangement or the title of "Saltbush Bill, J.P., and Other Verses". Table of Contents Song of the Pen Not for the love of women toil we, we of the craft, Song of the Wheat We have sung the song of the droving days, Brumby's Run It lies beyond the Western Pines Saltbush Bill on the Patriarchs Come all you little rouseabouts and climb upon my knee; The Reverend Mullineux I'd reckon his weight at eight-stun-eight, page 2 / 122 The Wisdom of Hafiz My son, if you go to the races to battle with Ikey and Mo, Saltbush Bill, J.P. -

![Three Elephant Power and Other Stories by Andrew Barton `Banjo' Paterson [Australian Poet, Reporter -- 1864-1941.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1470/three-elephant-power-and-other-stories-by-andrew-barton-banjo-paterson-australian-poet-reporter-1864-1941-2441470.webp)

Three Elephant Power and Other Stories by Andrew Barton `Banjo' Paterson [Australian Poet, Reporter -- 1864-1941.]

Three Elephant Power and Other Stories by Andrew Barton `Banjo' Paterson [Australian Poet, Reporter -- 1864-1941.] Three Elephant Power and Other Stories By A. B. Paterson, Author of The Man from Snowy River, Rio Grande, Saltbush Bill, J.P., An Outback Marriage, Etc. Contents Three Elephant Power The Oracle The Cast-iron Canvasser The Merino Sheep The Bullock White-when-he's-wanted The Downfall of Mulligan's The Amateur Gardener Thirsty Island Dan Fitzgerald Explains The Cat Sitting in Judgment The Dog The Dog -- as a Sportsman Concerning a Steeplechase Rider Victor Second Concerning a Dog-fight His Masterpiece Done for the Double Three Elephant Power "Them things," said Alfred the chauffeur, tapping the speed indicator with his fingers, "them things are all right for the police. But, Lord, you can fix 'em up if you want to. Did you ever hear about Henery, that used to drive for old John Bull -- about Henery and the elephant?" Alfred was chauffeur to a friend of mine who owned a very powerful car. Alfred was part of that car. Weirdly intelligent, of poor physique, he might have been any age from fifteen to eighty. His education had been somewhat hurried, but there was no doubt as to his mechanical ability. He took to a car like a young duck to water. He talked motor, thought motor, and would have accepted -- I won't say with enthusiasm, for Alfred's motto was `Nil admirari' -- but without hesitation, an offer to drive in the greatest race in the world. He could drive really well, too; as for belief in himself, after six months' apprenticeship in a garage he was prepared to vivisect a six-cylinder engine with the confidence of a diplomaed bachelor of engineering. -

Henry Lawson at Bourke

35 JOHN BARNES The making of a legend: Henry Lawson at Bourke ‘If you know Bourke, you know Australia’, Henry Lawson wrote to Edward Garnett in February 1902, a few months before returning to Australia from England. He explained to Garnett that his new collection of stories, which he then called ‘The Heart of Australia’, was ‘centred at Bourke and all the Union leaders are in it’.1 (When published later that year it was entitled Children of the Bush – a title probably chosen by the London publisher.) A decade after he had been there, Lawson was revisiting in memory a place that had had a profound influence on him. It is no exaggeration to say that his one and only stay in what he and other Australians called the ‘Out Back’ was crucial to his development as a prose writer. Without the months that he spent in the north- west of New South Wales, it is unlikely that he would ever have achieved the legendary status that he did as an interpreter of ‘the real Australia’. II In September 1892, Henry Lawson travelled the 760-odd kilometres from Sydney to Bourke by train, his fare paid by JF Archibald, editor of the Bulletin, who also gave him £5 for living expenses. Some time after Lawson’s death, his friend and fellow writer, EJ Brady, described how this came about. Through his contributions to the Bulletin and several other journals, Lawson had become well known as a writer, primarily as a versifier; but he found it almost impossible to make a living by his writing. -

James Tyson, Millionaire

JAMES TYSON, MILLIONAIRE by Lady Fletcher Read at a Meeting of the Society on 28 October 1982 The story of James Tyson, is in its way a romance, and far more worthy of relating than many of the serials that clog our television screens. It would make a very interesting series, educational and excitmg. It begins in a village in Yorkshire - Pontefract; one of those villages so different from our own, where the houses crowd closely to each other and to the street, where ducks swim lazily on the village pond, the half-timbered inn is the centre of community life, and in this case, the court house looks over the vUIage green. On a sunny morning in April 1808 a worried-looking sergeant is striding down the street. In his white trousers, red jacket, black shiny boots and black shako. Sergeant William Tyson is an impressive figure. He is going to the Court House, to which scattered groups of people are also making their way, for it is the time of the assizes. Among the prisoners in the dock is the Sergeant's handsome wife, Isabella. She stands, baby in arms, to answer the charge of petty larcency. This is described as "the theft of an article under the value of one shilling". Now we face a dilemma. Do we use the bald description of her crime found in the criminal list in the Mitchell Library - "stealing so many yards of gingham", or do we use the colorful story that is the family legend. If we choose the latter, we should have a flashback to the scene in the village street. -

Banjo Paterson Park Banjo Paterson Yass Ten Dollar Note

Banjo Paterson Park Banjo Paterson Yass Ten Dollar Note Banjo Paterson 1864 - 1941 Andrew Barton Paterson In the 1950’s Yass very proudly dedicated a My little collie pup works silently and wide park in the township to the memory of Banjo Paterson. As silent as a fox, you’ll see her come and go A shadow through the rocks, where ash and Yass Valley Information Centre You can wander around the rose garden and messmate grow 259 Comur Street , Yass admire his bust in bonze, excerpts from some Then list to sight and sound, behind some 1300 886 014 of his most well known poems as well as rugged steep, she works her way around and yassvalley.com.au information regarding his connection to the gathers up the sheep area about his life. Mountain Squatter Updated November 2018 Banjo Paterson Banjo Paterson Banjo Paterson Early Days School Days Coodravale Andrew Barton (Bartie) Paterson was the A governess was employed by the The love of the bush never left ‘Banjo’, a oldest of seven Paterson children. He was Paterson’s to teach Bartie to read and pen name he took from a horse, owned by five when his father moved to ‘Illalong write, as the Paterson household was his family. Station’ near Binalong. never lacking in an appreciation of the things of culture. After years in the city, he was ready to The station lay on the main route between return to his ‘Mountain Station’ and the Sydney & Melbourne, so there were Bartie started school in Binalng. The school opportunity came through an frequent travellers along the road from was four miles from his hone at Illalong, advertisement in the Town & Country bullockies to Cobb & Co coaches. -

Henry Lawson - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Henry Lawson - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Henry Lawson(17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) Henry Lawson was an Australian writer and poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial period and is often called Australia's "greatest writer". He was the son of the poet, publisher and feminist <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/louisa-lawson/">Louisa Lawson</a>. <b>Early Life</b> Henry Lawson was born in a town on the Grenfell goldfields of New South Wales. His father was Niels Herzberg Larsen, a Norwegian-born miner who went to sea at 21, arrived in Melbourne in 1855 to join the gold rush. Lawson's parents met at the goldfields of Pipeclay (now Eurunderee, New South Wales) Niels and Louisa married on 7 July 1866; he was 32 and she, 18. On Henry's birth, the family surname was anglicised and Niels became Peter Lawson. The newly- married couple were to have an unhappy marriage. Peter Larsen's grave (with headstone) is in the little private cemetery at Hartley Vale New South Wales a few minutes walk behind what was Collitt's Inn. Henry Lawson attended school at Eurunderee from 2 October 1876 but suffered an ear infection at around this time. It left him with partial deafness and by the age of fourteen he had lost his hearing entirely. He later attended a Catholic school at Mudgee, New South Wales around 8 km away; the master there, Mr. -

Teachers' Notes Banjo and Lawson

Teachers’ notes Banjo and Lawson Timeline 1831 to 1993 I developed this Timeline during my research and writing process. Like most of my research the majority of the information gathered never made it directly into the play, but I still think it will be of interest to students in their studies as it was for me. 1831 The HERALD (Sydney) later to become the Sydney Morning Herald Newspaper is first printed 1854 - The 1st Australian Telegraph line is erected and starts operations between Melbourne and Williamstown. It is 17 Kilometre long. This is only 10 years after the world’s first telegraph line operates in USA. 1860’s The life expectancy of Male Australians born in the 1860’s is 47. 1864 17th February Andrew Barton “Banjo” Paterson born near Orange, NSW. Died 1941 aged 77. 1867 The telegraph line now connects Brisbane, Melbourne, Adelaide and via the longest undersea cable in the world, at the time, Tasmania. 1867 7th June Henry Archibald Hertzberg Lawson born in Grenfell NSW. Died 1922 aged 55. 1872 the Telegraph line is completed between Adelaide and Darwin and is connected to an underwater cable that goes from Darwin to Java and from there all the way across Europe to England. 1880 30th January The Bulletin magazine is first published – it is a weekly publication and becomes known as the ‘bushman’s bible’. 1882 – 9th December Brisbane is the first town in Australia to turn on eight electric street lights in Queen Street -the main street. This is Australia’s first recorded use of electricity for public purposes.