The Fragile Status Quo in Northeast Syria | the Washington Institute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC North East Syria Displacement 28 October 2019

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC North East Syria displacement 28 October 2019 OVERVIEW 105,574 The onset of military operations in Northeast Syria by the Turkish army and allied non-state groups on 9 October has forced huge People currently displaced numbers of people to flee their homes. Around 105,574 remain displaced as of 28 October, and an additional 96,855 people were displaced and have since returned. Of those currently displaced, 98,798 are from Al Hassakeh and Ar Raqqa, and 6,776 are from 96,855 Aleppo. Displaced people are finding shelter with friends and family and also in informal settlements and collective shelters. People reported to have returned There are 69 such shelters in Al Hasakeh Governorate alone. Over 12,200 people have reportedly been displaced into neighboring Iraq. Prior to 9 October, Northeast Syria already hosted a total of 710,000 people displaced from earlier phases of the conflict, around 91,000 of whom remain in Al Hol, Areesha, Mahmoudi, Newroz and Roj camps. North East Syria Newroz Roj Jawadiyah 4 ] ] 5 1,808 Qahtaniyyeh TURKEY Darbasiyah Amuda Ain al Arab Jarablus Tell Ras Al Ain Abiad 2 To Iraq Mabroka * Menbij Al-Hasakeh Tal Hmis 12,238 Suluk 2 Ein Issa Tal Tamer Ar-Raqqa 51 Areesha Al-Hol Legend To Aleppo Camp AlKalta Alzahira Tal Alsamn Janoby Almazuneh Abu 8,475 68,577 IDP collective shelters / No. Hatash Jurneyyeh Abu Kubry Royan Khashab Informal IDP settlments Alajaj Jarwah Alrasheed Tawaiheneh Alasdyah-Alfqubour Road (M4) AlGhaba Al Fateh Rabeah Mazraat Yareb Tal AlBayah Al-Hasakeh Lake/river Mahmoudli AlSalhabeh AlKhatonyeh Population movement Alqarbia Abu Kubea 7,321 Alhamam 6,290 Empty Camp Henedeh Ath-Thawra Displaced TO Deir-ez-Zor 35k Sur 600 74k The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Syria Drought Response Plan

SYRIA DROUGHT RESPONSE PLAN A Syrian farmer shows a photo of his tomato-producing field before the drought (June 2009) (Photo Paolo Scaliaroma, WFP / Surendra Beniwal, FAO) UNITED NATIONS SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC - Reference Map Elbistan Silvan Siirt Diyarbakir Batman Adiyaman Sivarek Kahramanmaras Kozan Kadirli TURKEY Viransehir Mardin Sanliurfa Kiziltepe Nusaybin Dayrik Zakhu Osmaniye Ceyhan Gaziantep Adana Al Qamishli Nizip Tarsus Dortyol Midan Ikbis Yahacik Kilis Tall Tamir AL HASAKAH Iskenderun A'zaz Manbij Saluq Afrin Mare Al Hasakah Tall 'Afar Reyhanli Aleppo Al Bab Sinjar Antioch Dayr Hafir Buhayrat AR RAQQA As Safirah al Asad Idlib Ar Raqqah Ash Shaddadah ALEPPO Hamrat Ariha r bu AAbubu a add D Duhuruhur Madinat a LATAKIA IDLIB Ath Thawrah h Resafa K l Ma'arat a Haffe r Ann Nu'man h Latakia a Jableh Dayr az Zawr N El Aatabe Baniyas Hama HAMA Busayrah a e S As Saiamiyah TARTU S Masyaf n DAYR AZ ZAWR a e n Ta rtus Safita a Dablan r r e Tall Kalakh t Homs i Al Hamidiyah d Tadmur E e uphrates Anah M (Palmyra) Tripoli Al Qusayr Abu Kamal Sadad Al Qa’im HOMS LEBANON Al Qaryatayn Hadithah BEYRUT An Nabk Duma Dumayr DAMASCUS Tyre DAMASCUS QQuneitrauneitra Ar Rutbah QUNEITRA Haifa Tiberias AS SUWAIDA IRAQ DAR’A Trebil ISRAELI S R A E L DDarar'a As Suwayda Irbid Jenin Mahattat al Jufur Jarash Nabulus Al Mafraq West JORDAN Bank AMMAN JERUSALEM Bayt Lahm Madaba SAUDI ARABIA Legend Elevation (meters) National capital 5,000 and above First administrative level capital 4,000 - 5,000 Populated place 3,000 - 4,000 International boundary 2,500 - 3,000 First administrative level boundary 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 050100150 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 km 600 - 800 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material 400 - 600 on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal 200 - 400 status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Study the Democratic Union Party's Political Project for Syria 0

www.jusoor.co Study 0 The Democratic Union Party’s Political Project for Syria www.jusoor.co Study 1 The Democratic Union Party’s Political Project for Syria www.jusoor.co Study 2 Contents Preface ........................................................................................................ 3 PYD’s Ideology towards Syria ................................................................... 4 PYD’s Project ......................................................................................... 4 The Decisions Related to the Founding Conference .............................. 6 2007 Amendments .................................................................................. 7 Amendments of 2012 .............................................................................. 9 Amendments of 2015 ............................................................................ 10 Amendments of 2017 ............................................................................ 10 Indications of Changes in the PYD’s Ideology .................................... 11 The PYD’s Policy and Activities towards Syria ...................................... 12 The Media Discourse ............................................................................ 12 Mass Demonstrations............................................................................ 16 The Possible New Trend of the PYD ....................................................... 17 The Outcomes .......................................................................................... -

Understanding Market Drivers in Syria 2 Table of Contents

Prepared by the Syria Independent Monitoring (SIM) team, January 2018 Understanding Market Drivers in Syria 2 Table of Contents Abbreviations 4 1. Executive summary 5 2. Introduction 7 2.1. Background.......................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Scope................................................................................................................... 7 2.3. Methodology........................................................................................................ 7 .. 3. Macroeconomic environment 9 4. Market and trade in the northern areas of Idleb, Aleppo and Hasakeh 11 4.1. Main market fows: supply and demand of food commodities .............................. 11 4.2. Price fuctuations ................................................................................................ 11 4.3. Market performance and competitiveness .......................................................... 13 4.4. Processing capacity ............................................................................................ 14 5. Mapping of olives/olive oil and herb/spice market systems 15 5.1. Overview of the spice and olive market systems in northern Syria ....................... 16 5.2. Current market structure ..................................................................................... 19 5.2.1. Market environment ................................................................................ 19 5.2.2. Trade routes from/into the areas of study ............................................ -

Assyrians Under Kurdish Rule: The

Assyrians Under Kurdish Rule e Situation in Northeastern Syria Assyrians Under Kurdish Rule The Situation in Northeastern Syria Silvia Ulloa Assyrian Confederation of Europe January 2017 www.assyrianconfederation.com [email protected] The Assyrian Confederation of Europe (ACE) represents the Assyrian European community and is made up of Assyrian national federations in European countries. The objective of ACE is to promote Assyrian culture and interests in Europe and to be a voice for deprived Assyrians in historical Assyria. The organization has its headquarters in Brussels, Belgium. Cover photo: Press TV Contents Introduction 4 Double Burdens 6 Threats to Property and Private Ownership 7 Occupation of facilities Kurdification attempts with school system reform Forced payments for reconstruction of Turkish cities Intimidation and Violent Reprisals for Self-Determination 9 Assassination of David Jendo Wusta gunfight Arrest of Assyrian Priest Kidnapping of GPF Fighters Attacks against Assyrians Violent Incidents 11 Bombings Provocations Amuda case ‘Divide and Rule’ Strategy: Parallel Organizations 13 Sources 16 4 Introduction Syria’s disintegration as a result of the Syrian rights organizations. Among them is Amnesty Civil War created the conditions for the rise of International, whose October 2015 publica- Kurdish autonomy in northern Syria, specifi- tion outlines destructive campaigns against the cally in the governorates of Al-Hasakah and Arab population living in the region. Aleppo. This region, known by Kurds as ‘Ro- Assyrians have experienced similar abuses. java’ (‘West’, in West Kurdistan), came under This ethnic group resides mainly in Al-Ha- the control of the Kurdish socialist Democratic sakah governorate (‘Jazire‘ canton under the Union Party (abbreviated PYD) in 2012, after PYD, known by Assyrians as Gozarto). -

Governing Rojava Layers of Legitimacy in Syria Contents

Research Paper Rana Khalaf Middle East and North Africa Programme | December 2016 Governing Rojava Layers of Legitimacy in Syria Contents Summary 2 Acronyms and Overview of Key Listed Actors 3 Introduction 5 PYD Pragmatism and the Emergence of ‘Rojava’ 8 Smoke and Mirrors: The PYD’s Search for Legitimacy Through Governance 10 1. Provision of security 12 2. Effectiveness in the provision of services 16 3. Diplomacy and image management 21 Conclusion: The Importance of Local Trust and Representation 24 About the Author 26 Acknowledgments 27 1 | Chatham House Governing Rojava: Layers of Legitimacy in Syria Summary • Syria is without functioning government in many areas but not without governance. In the northeast, the Democratic Union Party (PYD) has announced its intent to establish the federal region of Rojava. The PYD took control of the region following the Syrian regime’s handover in some Kurdish-majority areas and as a consequence of its retreat from others. In doing so, the PYD has displayed pragmatism and strategic clarity, and has benefited from the experience and institutional development of its affiliate organization, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). The PYD now seeks to further consolidate its power and to legitimize itself through the provision of security, services and public diplomacy; yet its local legitimacy remains contested. • The provision of security is paramount to the PYD’s quest for legitimacy. Its People’s Defense Units (YPG/YPJ) have been an effective force against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), winning the support of the local population, particularly those closest to the front lines. -

In PDF Format, Please Click Here

Deprivatio of Existence The use of Disguised Legalization as a Policy to Seize Property by Successive Governments of Syria A special report sheds light on discrimination projects aiming at radical demographic changes in areas historically populated by Kurds Acknowledgment and Gratitude The present report is the result of a joint cooperation that extended from 2018’s second half until August 2020, and it could not have been produced without the invaluable assistance of witnesses and victims who had the courage to provide us with official doc- uments proving ownership of their seized property. This report is to be added to researches, books, articles and efforts made to address the subject therein over the past decades, by Syrian/Kurdish human rights organizations, Deprivatio of Existence individuals, male and female researchers and parties of the Kurdish movement in Syria. Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) would like to thank all researchers who contributed to documenting and recording testimonies together with the editors who worked hard to produce this first edition, which is open for amendments and updates if new credible information is made available. To give feedback or send corrections or any additional documents supporting any part of this report, please contact us on [email protected] About Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) STJ started as a humble project to tell the stories of Syrians experiencing enforced disap- pearances and torture, it grew into an established organization committed to unveiling human rights violations of all sorts committed by all parties to the conflict. Convinced that the diversity that has historically defined Syria is a wealth, our team of researchers and volunteers works with dedication at uncovering human rights violations committed in Syria, regardless of their perpetrator and victims, in order to promote inclusiveness and ensure that all Syrians are represented, and their rights fulfilled. -

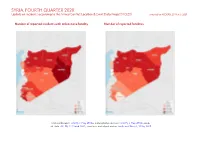

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 1539 195 615 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2018 to December 2020 2 Battles 650 308 1174 Violence against civilians 394 185 218 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 364 1 1 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 158 0 0 Riots 9 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 3114 689 2008 Disclaimer 7 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from December 2018 to December 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Empty Paper for the Cover Photo

Empty paper for the cover photo "How could you be a Foreigner with an Arabic Tongue?!" www.stj-sy.com "How could you be a Foreigner with an Arabic Tongue?!" Statement of Mahmoud al-Muhammad bin Ismail Page | 2 "How could you be a Foreigner with an Arabic Tongue?!" www.stj-sy.com Mahmoud always feels ashamed whenever he present his “ red card, that he considers worthless, since it is for stateless Syrian Kurds, who are deprived of all of his citizenship rights . Mahmoud al-Muhammad bin Ismail was born in the al-Qahtaniyah/Tarbassiyah town in al- Hasakah Governorate in 1960. He is now married with nine children. Most of Mahmoud’s family members are stateless, specifically ajanib1 including his father and children. Mahmoud spoke to STJ field researcher during an interview conducted in March 2018: "My father owned a small shop in Soufia village, al-Qahtaniyah, which was the only one of its kind there, and he was well known among villagers.He became an ajnabi as a result of the census, without knowing why and his status was transmitted to me and my siblings. However, in spite of this, my brother was forced to perform compulsory military service in the Syrian army, spending three years and a half in Ad Dumayr city-Damascus countryside, before he was discharged and given back his red card. After three months, his name was included in reserve military service lists, but he went to the Conscription Division and told the officials that he would not serve this time, even if they threatened to chop him to pieces. -

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 30 March - 5 April 2020

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 30 March - 5 April 2020 SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST | Levels of Conflict in northwest Syria remained elevated for the second consecutive week, as Turkish military personnel and equipment continued to arrive to Idleb. Inside the Turkish-held areas of northern Aleppo Governorate, opposition armed groups continued their looting and extortion activity against civilians. An attack against an opposition affiliated National Police Officer highlighted the growing number of attacks against the entity in the previous month. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | Tensions over kidnapping and clashes continue between communal militias Dara’a and As-Sweida. Government of Syria (GoS)-aligned personal faced continuing attacks in Daraa Governorate. • NORTHEAST | Shelling exchanges around Turkish-held Operation Peace Spring areas increased, while Turkish-backed opposition armed groups and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) clashed on the ground. Jailed ISIS members staged a riot to escape a prison in Hassakah. ISIS also attacked SDF and pro-Iran forces in Deir-ez-Zor. Members of the Asayish (Kurdish Intelligence) and National Defense Forces (NDF) exchanged fire in Qamishli City. Figure 1: Dominant actors’ area of control and influence in Syria as of 5 April 2020. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. Also, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 5 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 30 March – 5 April 2020 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 For a second consecutive week, there were elevated levels of conflict activity in the northwest of Syria. The Government of Syria (GoS) shelled 14 locations, 26 times2 during the week, compared to 22 locations targeted 36 times by shelling and small arms fire the previous week. -

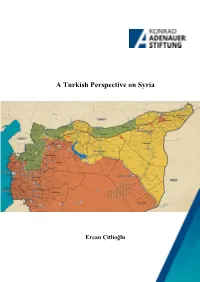

A Turkish Perspective on Syria

A Turkish Perspective on Syria Ercan Çitlioğlu Introduction The war is not over, but the overall military victory of the Assad forces in the Syrian conflict — securing the control of the two-thirds of the country by the Summer of 2020 — has meant a shift of attention on part of the regime onto areas controlled by the SDF/PYD and the resurfacing of a number of issues that had been temporarily taken off the agenda for various reasons. Diverging aims, visions and priorities of the key actors to the Syrian conflict (Russia, Turkey, Iran and the US) is making it increasingly difficult to find a common ground and the ongoing disagreements and rivalries over the post-conflict reconstruction of the country is indicative of new difficulties and disagreements. The Syrian regime’s priority seems to be a quick military resolution to Idlib which has emerged as the final stronghold of the armed opposition and jihadist groups and to then use that victory and boosted morale to move into areas controlled by the SDF/PYD with backing from Iran and Russia. While the east of the Euphrates controlled by the SDF/PYD has political significance with relation to the territorial integrity of the country, it also carries significant economic potential for the future viability of Syria in holding arable land, water and oil reserves. Seen in this context, the deal between the Delta Crescent Energy and the PYD which has extended the US-PYD relations from military collaboration onto oil exploitation can be regarded both as a pre-emptive move against a potential military operation by the Syrian regime in the region and a strategic shift toward reaching a political settlement with the SDF. -

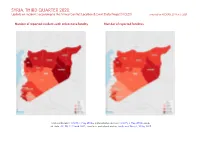

SYRIA, THIRD QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, THIRD QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, THIRD QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 1439 241 633 violence Development of conflict incidents from September 2018 to September Battles 543 232 747 2020 2 Violence against civilians 400 209 262 Strategic developments 394 0 0 Methodology 3 Protests 107 0 0 Conflict incidents per province 4 Riots 12 1 2 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 2895 683 1644 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Disclaimer 7 Development of conflict incidents from September 2018 to September 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, THIRD QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data.