COMMUNICATION PATTERNS in PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARIES 1912-2000: Knowing the Rules of the Game By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1996 Republican Party Primary Election March 12, 1996

Texas Secretary of State Antonio O. Garza, Jr. Race Summary Report Unofficial Election Tabulation 1996 Republican Party Primary Election March 12, 1996 President/Vice President Precincts Reporting 8,179 Total Precincts 8,179 Percent Reporting100.0% Vote Total % of Vote Early Voting % of Early Vote Delegates Lamar Alexander 18,615 1.8% 11,432 5.0% Patrick J. 'Pat' Buchanan 217,778 21.4% 45,954 20.2% Charles E. Collins 628 0.1% 153 0.1% Bob Dole 566,658 55.6% 126,645 55.8% Susan Ducey 1,123 0.1% 295 0.1% Steve Forbes 130,787 12.8% 27,206 12.0% Phil Gramm 19,176 1.9% 4,094 1.8% Alan L. Keyes 41,697 4.1% 5,192 2.3% Mary 'France' LeTulle 651 0.1% 196 0.1% Richard G. Lugar 2,219 0.2% 866 0.4% Morry Taylor 454 0.0% 124 0.1% Uncommitted 18,903 1.9% 4,963 2.2% Vote Total 1,018,689 227,120 Voter Registration 9,698,506 % VR Voting 10.5 % % Voting Early 2.3 % U. S. Senator Precincts Reporting 8,179 Total Precincts 8,179 Percent Reporting100.0% Vote Total % of Vote Early Voting % of Early Vote Phil Gramm - Incumbent 837,417 85.0% 185,875 83.9% Henry C. (Hank) Grover 71,780 7.3% 17,312 7.8% David Young 75,976 7.7% 18,392 8.3% Vote Total 985,173 221,579 Voter Registration 9,698,506 % VR Voting 10.2 % % Voting Early 2.3 % 02/03/1998 04:16 pm Page 1 of 45 Texas Secretary of State Antonio O. -

Governor Brown's Transportation Funding Plan

Governor Brown’s Transportation Funding Plan This proposal is a balance of new revenue and reasonable reforms to ensure efficiency, accountability and performance from each dollar invested to improve California’s transportation system. Governor Brown’s Transportation Funding Plan Frequently Asked Questions This proposal is a combination of new revenue and reform with measurable targets for improvements including regular reporting, streamlined projects with exemptions for infrastructure repairs and flexibility on hiring for new workload. How much does this program provide overall for transportation improvements? • Over the next decade, the Governor’s Transportation Funding Plan provides an estimated $36 billion in funding for transportation, with an emphasis on repairing and maintaining existing transportation infrastructure and a commitment to repay an additional $879 million in outstanding loans. How much does it require the average vehicle owner in California to pay? • The proposal equates to roughly 25-cents per motorist per day according to the Department of Finance. The latest TRIP* study released, and subsequent article in the Washington Post, showed that Californians spend on average $762 annually on vehicle repair costs due to wear and tear / road conditions, etc. http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonkblog/ wp/2015/06/25/why-driving-on-americas-roads-can-be-more-expensive-than-you-think/ A figure that should go down significantly with improved road conditions. How will the program improve transportation in California over the next decade? • Within 10 years, with this plan, the state has made a commitment to get our roadways up to 90% good condition. Today, 41% of our pavement is either distressed or needs preventative maintenance. -

President - Telephone Calls (2)” of the Richard B

The original documents are located in Box 17, folder “President - Telephone Calls (2)” of the Richard B. Cheney Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 17 of the Richard B. Cheney Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library ,;.._.. ~~;·.~·- .·.· ~-.. .· ..·. ~- . •.-:..:,.:·-. .-~-:-} ·· ~·--· :·~·-.... ~.-.: -~ ·":~· :~.·:::--!{;.~·~ ._,::,.~~~:::·~=~:~;.;;:.;~.;~i8JitA~w~;ri~r·•v:&;·~ ·e--.:.:,;,·.~ .. ~;...:,.~~,·-;;;:,:_ ..• THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON K~ t.l T ..u:. \(. y l\,~~;'"Y # 3 < . ~OTt.~ ~~~ -"P1ltS.tDI!'-'l' ~t&.. c. -y"Ro"&At.&.y vasir Ke'-',.uc..~ty .. ,... -f.le.. tL>e.e..te.NI) 0 ~ Mf'\y l'i, IS. Th\.s will he ~t.\ oF' ~ 3 ' . $ T _,.-c... &~• u~ +~ \\.)t.lvct t. Te~t.>~s••• ,..,.~ fh:.""'''". ORIGINAL . •· . SPECIAL Do RETIRED· TO . · CUMENTS Ftf. .E . ~- .~ ·. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON RECOMMENDED TELEPHONE CALL TO Congressman Tim Lee Carter {Kentucky, 5th District) 225-4601 DATE Prior to May 25 primary in Kentucky RECOMMENDED BY Rog Morton, Stu Spencer PURPOSE To thank the Congressman for his April 5th endorsement and for the assistance of his organization. -

Stassen Farmers Agreed and Stassen Making Life Career

124 So. St. Paul/lnver Grove Heights,West St. PauyMendota Heights Sun.CurrenWVednesday, March 14, 2001 www.mnSun.com buyers to pay higher prices. The Glen said. "I think his peace- Stassen farmers agreed and Stassen making life career ... came out was successful in negotiating of his hometown labor strife." higher milk prices. The lessons learned as a From Page 1A Another life-changing mo- young man in Dakota County ment in Stassen's life as county would remain with Stassen into For instance, while serving attorney occurred during a his later years as governor, and as county attorney, Stassen strike at South St. Paul's stock- later as foreign diplomat. helped to settle a dispute be- yards, Glen said. The National While governor, Stassen tween local dairy farmers and Guard surrounded the stock- helped pass legislation requir- St. Paui merchants. The dairy yards with bayonets and forced ing workers to wait 30 days be- farmers had threatened to block the striking meat packers away fore being allowed to strike. a local highway and dump milk from the building so non-union "He cut down the number of in protest o[ low milk prices. workers could get in. strikes by about one-third with "Dad said to them, 'If you do Glen said his father always this law," Glen said. that, we will need to arrest you, remembered that scene because In L943, Stassen left Min- and there will probably be vio- of the unjust treatment of work- nesota to fight in World War II. lence and other farmers will get CIS. -

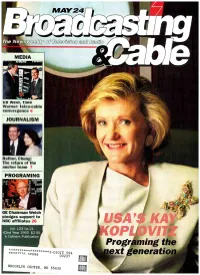

Ext Generatio

MAY24 The News MEDIA nuo11011 .....,1 US West, Time Warner: telco-cable convergence 6 JOURNALISM Rather, Chung: The return of the anchor team PROGRAMING GE Chairman Welch pledges support to NBC affiliates 26 U N!'K; Vol. 123 No.21 62nd Year 1993 $2.95 A Cahners Publication OP Progr : ing the no^o/71G,*******************3-DIGIT APR94 554 00237 ext generatio BROOKLYN CENTER, MN 55430 Air .. .r,. = . ,,, aju+0141.0110 m,.., SHOWCASE H80 is a re9KSered trademark of None Box ice Inc. P 1593 Warner Bros. Inc. M ROW Reserve 5H:.. WGAS E ALE DEMOS. MEN 18 -49 MEN 18 -49 AUDIENCE AUDIENCE PROGRAM COMPOSITION PROGRAM COMPOSITION STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE 9 37% WKRP IN CINCINNATI 25% HBO COMEDY SHOWCASE 35% IT'S SHOWTIME AT APOLLO 24% SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE 35% SOUL TRAIN 24% G. MICHAEL SPORTS MACHINE 34% BAYWATCH 24% WHOOP! WEEKEND 31% PRIME SUSPECT 24% UPTOWN COMEDY CLUB 31% CURRENT AFFAIR EXTRA 23% COMIC STRIP LIVE 31% STREET JUSTICE 23% APOLLO COMEDY HOUR 310/0 EBONY JET SHOWCASE 23% HIGHLANDER 30% WARRIORS 23% AMERICAN GLADIATORS 28% CATWALK 23% RENEGADE 28% ED SULLIVAN SHOW 23% ROGGIN'S HEROES 28% RUNAWAY RICH & FAMOUS 22% ON SCENE 27% HOLLYWOOD BABYLON 22% EMERGENCY CALL 26% SWEATING BULLETS 21% UNTOUCHABLES 26% HARRY & THE HENDERSONS 21% KIDS IN THE HALL 26% ARSENIO WEEKEND JAM 20% ABC'S IN CONCERT 26% STAR SEARCH 20% WHY DIDN'T I THINK OF THAT 26% ENTERTAINMENT THIS WEEK 20% SISKEL & EBERT 25% LIFESTYLES OF RICH & FAMOUS 19% FIREFIGHTERS 25% WHEEL OF FORTUNE - WEEKEND 10% SOURCE. NTI, FEBRUARY NAD DATES In today's tough marketplace, no one has money to burn. -

Vitale Not Just Dry Bones Provides Scholarship

_ I OBSERVER Friday, November 10, 1995* Vol. XXVII No. 54 INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY'S ■ F aculty S enate Last summer, Notre Dame student Jenny Malloy: Future Richtsmeier assisted Professor Susan S h erid a n in th e unearthing of ancient looks bright for bones in Israel as part of the Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program. The ND programs remains were studied By GWENDOLYN NORGLE and for information on the cultural profile of the Assistant News Editor Byzantine civilization. RUSSELL WILLIAMS The program was News Writer founded by Sheridan to provide undergrad University President Father Edward Malloy uates with experience addressed the Faculty Senate Wednesday in the anthropological night, and a number of issues topped his field of study. Photos provided by Jenny discussion. Richtsmeier Malloy responded to a number of questions concerning the progress of the Colloquy, the selection of the Provost, financial aid, staff salaries, and graduate education that were submitted to him by the Senate prior to the meeting. In his opening remarks to this discussion, Malloy said, “There are reasons to be opti mistic in looking toward our future.” Although he pointed out a number of these reasons for optimism, Malloy described the lack of financial aid as a significant problem. Not just dry bones “Financial aid looms very, very large to me,” he said. “We hope to be able to build our financial aid resources. We have a dual strat Research program allows ND student egy to continue as aggressively as we can to solicit funds." to spend summer in Israel studying Malloy mentioned tuition increases as another one of the main financial issues that the remains of a Byzantine culture the University must confront. -

Mcmahon EC.Pdf

1992 Junior Bird Tournament Extra Credit Questions by · Col.l.een McMahon 46. 25 points By now everyone should be somewhat familiar with the crop of presidential hopefuls who went stumping in New Hampshire. All together, 62 candidates filed for this primary. See how many of these lesser-known politicos you can identify, for 5 points each: a. She is the candidate for the New Alliance Party, as she was in 1988. Lenora Fulani b. This tv comedian has run several times and is doing so again this year in spite of bankruptcy. Pat Paulsen c. The "wild-eyed libertarian" sent his form in from the federal prison where he is serving a term for mail fraud. Lyndon LaRouche d. He played Billy Jack in the 1970s movies; now he wants to follow in the footsteps of another movie star-turned-president. Tom Laughlin e. It just wouldn't be an election year without this candidate, the 84-year-old former governor of Minnesota, who has been running unsuccessfully since 1944. Harold Stassen 47. 20 points Identify these famous mythological wives, given the names of their husbands, for 5 points each: a. Agamemnon Clytemnestra b. Odysseus Penelope c. Oedipus Jocasta d. Priam Hecuba 48. 30 points Art Nouveau was an early 20th Century movement whose influences spread from painting to jewelry and furniture design. For 10 points each, identify these artists associated with Art Nouveau: a. Austrian, foremost practitioner of Art Nouveau in Vienna, works include The Kiss: Gustav Klimt b. His New York City studios specialized in favrile glasswork, characterized by iridescent colors. -

Jeff Greenfield

Jeff Greenfield Political Analyst One of America’s most respected political analysts, Jeff Greenfield has spent more than 30 years on network television, including CNN, ABC News, CBS, and as an anchor on PBS’ Need to Know. A five-time Emmy Award-winner, he is known for his quick wit and savvy insight into politics, history, the media and current events. Twice he was named to TV Guide‘s All-Star News “Dream Team” as best political commentator and was cited by the Washington Journalism Review as “the best in the business” for his media analysis. Greenfield has served as anchor booth analyst or floor reporter for every national political convention since 1988 and reported on virtually every important domestic political story in recent decades. He looks at American political history "through a fictional looking glass" in his national bestseller, Then Everything Changed: Stunning Alternate Histories of American Politics -- JFK, RFK, Carter, Ford, Reagan, released to great acclaim in March 2011. The New York Times called it "shrewdly written, often riveting." A follow-up e-book, 43*: When Gore Beat Bush—A Political Fable, was published in September 2012, and his latest, If Kennedy Lived: The First and Second Terms of President John F. Kennedy: An Alternate History, was released in October 2013. A former speechwriter for Robert F. Kennedy, Greenfield has authored or co-authored 12 books including national bestselling novel The People’s Choice, The Real Campaign, and Oh, Waiter! One Order of Crow!, an insider account of the contested 2000 presidential election. From 1998-2007 Greenfield was a senior analyst for CNN, serving as lead analyst for its coverage of the primaries, conventions, presidential debates and election nights. -

Remarks at a Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee Dinner in Cambridge, Massachusetts July 28, 2000

July 28 / Administration of William J. Clinton, 2000 Remarks at a Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee Dinner in Cambridge, Massachusetts July 28, 2000 Well, Swanee, if I had a bell right now, I chusetts Members that are here are taking a would certainly ring it. [Laughter] You’ve been big chance on me tonight because I haven’t ringing my bell for years now. [Laughter] She’s been to bed in 16 days—[laughter]—and I, been very great for my personal maturity, frankly, don’t know what I’m saying. [Laughter] Swanee has, because I know every time I see And tomorrow I won’t remember it. her coming, she’s going to tell me about some- And the only thing I can think of that they thing else I haven’t done. [Laughter] And it allowed me to come here, after being up—you takes a certain amount of grown-upness to wel- know, I’ve been up in the Middle East peace come that sort of message—[laughter]—with the talks, and then I flew to Okinawa for 3 days consistency with which she has delivered it over and came back, over there and back in 3 days— the years. [Laughter] Actually, I love it. You and then I said, ‘‘Well, surely, you’re going to know, I mean, I sort of hired on to work, so let me rest.’’ And they said, ‘‘No, you missed somebody has to tell me what to do from time 2 weeks of work, and the Congress is fixing to time. It’s great. -

Candidates Prepare for Final Showdown

Matawan holds onto lead in Register Top Ten, 1B MONMOUTH COUNTY'S HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER SINCE 1878 ister )AY. NOV 8. 1988 VOL. 111 NO. .13 25 i Lawyer: Hunt Meet Candidates prepare not legal for final showdown By VIRGINIA KEMTDORRI8 bid to topple incumbent U.S. Sen. Frank Lautenberg. THE REGISTER BySEAMUSMcORAW The latest Eagleton poll, however, gives Lautenberg a THE REGISTER solid 12-point lead over the one-time Heisman Tro- phy winner and Rhodes scholar. MIDDLETOWN — The state On the congressional level, the race to fill How- Attorney General's Office will Politicians and campaign workers spent much of ard's seat — in which Libertarian Laura Stewart it look into whether the annual Hunt yesterday in a last-minute push before today's general also a candidate — has drawn national attention, in Race Meet operates legally be- election. pan because it is one of the few seats nationwide with cause of inquiries made by local "We've been out all weekend," said Wendy Do- no incumbent. attorney Larry S. Loigman. nath, a spokesman for 3rd Congressional District The picture is further complicated by the fact that Loigman, who has vowed to hopeful Joseph Azzolina. with Howard's death and the resignation of Demo- "make sure that this year's hunt is Azzolina is hoping to top Democratic state Sen. cratic Rep. Peter Rodino of Newark, the state's pres- the last one," last month contacted Frank Pallone in the race to fill the seat left vacant by tige level in Congress is reported to be on the decline. -

2006-2007 Impact Report

INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION The Global Network for Women in the News Media 2006–2007 Annual Report From the IWMF Executive Director and Co-Chairs March 2008 Dear Friends and Supporters, As a global network the IWMF supports women journalists throughout the world by honoring their courage, cultivating their leadership skills, and joining with them to pioneer change in the news media. Our global commitment is reflected in the activities documented in this annual report. In 2006-2007 we celebrated the bravery of Courage in Journalism honorees from China, the United States, Lebanon and Mexico. We sponsored an Iraqi journalist on a fellowship that placed her in newsrooms with American counterparts in Boston and New York City. In the summer we convened journalists and top media managers from 14 African countries in Johannesburg to examine best practices for increasing and improving reporting on HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria. On the other side of the world in Chicago we simultaneously operated our annual Leadership Institute for Women Journalists, training mid-career journlists in skills needed to advance in the newsroom. These initiatives were carried out in the belief that strong participation by women in the news media is a crucial part of creating and maintaining freedom of the press. Because our mission is as relevant as ever, we also prepared for the future. We welcomed a cohort of new international members to the IWMF’s governing board. We geared up for the launch of leadership training for women journalists from former Soviet republics. And we added a major new journalism training inititiative on agriculture and women in Africa to our agenda. -

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation Yueqin Yang, M.A. Mentor: Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D. This thesis commits to highlighting major stereotypes concerning Asians and Asian Americans found in the U.S. media, the “Yellow Peril,” the perpetual foreigner, the model minority, and problematic representations of gender and sexuality. In the U.S. media, Asians and Asian Americans are greatly underrepresented. Acting roles that are granted to them in television series, films, and shows usually consist of stereotyped characters. It is unacceptable to socialize such stereotypes, for the media play a significant role of education and social networking which help people understand themselves and their relation with others. Within the limited pages of the thesis, I devote to exploring such labels as the “Yellow Peril,” perpetual foreigner, the model minority, the emasculated Asian male and the hyper-sexualized Asian female in the U.S. media. In doing so I hope to promote awareness of such typecasts by white dominant culture and society to ethnic minorities in the U.S. Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation by Yueqin Yang, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of American Studies ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ James M. SoRelle, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Xin Wang, Ph.D.