Willie Nelson and the Mom and Pop Grocery Aid Concert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Farm Aid: a Case Study of a Charity Rock Organization Andrew Palen University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 Farm Aid: a Case Study of a Charity Rock Organization Andrew Palen University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Palen, Andrew, "Farm Aid: a Case Study of a Charity Rock Organization" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1399. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1399 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FARM AID: A CASE STUDY OF A CHARITY ROCK ORGANIZATION by Andrew M. Palen A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee December 2016 ABSTRACT FARM AID: A CASE STUDY ON THE IMPACT OF A CHARITY ROCK ORGANIZATION by Andrew M. Palen The University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor David Pritchard This study examines the impact that the non-profit organization Farm Aid has had on the farming industry, policy, and the concert realm known as charity rock. This study also examines how the organization has maintained its longevity. By conducting an evaluation on Farm Aid and its history, the organization’s messaging and means to communicate, a detailed analysis of the past media coverage on Farm Aid from 1985-2010, and a phone interview with Executive Director Carolyn Mugar, I have determined that Farm Aid’s impact is complex and not clear. -

An All Day Music and Homegrown Festival from Noon to 11 Pm

AN ALL DAY MUSIC AND HOMEGROWN FESTIVAL FROM NOON TO 11 PM. THIS YEAR’S LINEUP INCLUDES: WILLIE NELSON & FAMILY, NEIL YOUNG, JOHN MELLENCAMP, DAVE MATTHEWS AND MORE TO BE ANNOUNCED. About Farm Aid FARM AID IS AMERICA’S LONGEST RUNNING CONCERTFORACAUSE. SINCE 1985, FARM AID CONCERTS HAVE CELEBRATED FAMILY FARMERS AND GOOD FOOD. KEY NUMBERS FOR FARM AID 2017 22k 16 22k Concert Goers Artist Performances People eating HOMEGROWN Concessions® 30 1,903,194,905 HOMEGROWN Media Impressions Village Experiences 3 About Farm Aid CONCERTGOER DEMOGRAPHICS FARM AID 2017 SURVEY Age Group 30% 20% 10% Gender 0% Age 18 -34 Age 35-44 Age 45-54 Age 55-64 Under Age 18 Above Age 65+ 40% Male Household Income 30% 20% 58% Female 10% 0% 150k+ Under $20k 75k - $99.9k $20k - $49.9k $50k - $74.9k 100k - 149.9k 4 About Farm Aid LOYALTY Willingness to Purchase from Farm Aid Sponsors 89% 5 About Farm Aid YOU’RE IN GOOD COMPANY WITH PAST FARM AID SPONSORS 6 About Farm Aid OUR ARTISTS Farm Aid board members Willie Nelson, Neil Young, John Mellencamp and Dave Matthews, joined by more than a dozen artists each year, all generously donate their performances for a full day of music. Farm Aid artists speak up with farmers at the press event on stage just before the concert, attended by 200+ members of the media. Farm Aid artists join farmers throughout the day on the FarmYard stage to discuss food and farming. 7 The Concert Marketing Benefits & Reach FARM AID PROVIDES AN EXCELLENT OPPORTUNITY FOR SPONSORS TO ASSOCIATE WITH ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT MISSIONS IN AMERICA: TO BUILD A VIBRANT, FAMILY FARMCENTERED SYSTEM OF AGRICULTURE AND PROMOTE GOOD FOOD FROM FAMILY FARMS. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. September 21, 2020 to Sun. September 27, 2020

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. September 21, 2020 to Sun. September 27, 2020 Monday September 21, 2020 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Plain Spoken: John Mellencamp TrunkFest with Eddie Trunk This stunning, cinematic concert film captures John with his full band, along with special guest Sturgis Motorycycle Rally - Eddie heads to South Dakota for the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally at the Carlene Carter, performing his most cherished songs. “Small Town,” “Minutes to Memories,” “Pop Buffalo Chip. Special guests George Thorogood and Jesse James Dupree join Eddie as he explores Singer,” “Longest Days,” “The Full Catastrophe,” “Rain on the Scarecrow,” “Paper in Fire,” “Authority one of America’s largest gatherings of motorcycle enthusiasts. Song,” “Pink Houses” and “Cherry Bomb” are some of the gems found on this spectacular concert film. 8:30 AM ET / 5:30 AM PT Rock & Roll Road Trip With Sammy Hagar 6:40 PM ET / 3:40 PM PT Livin’ Live - The season 2 Best of Rock and Roll Road Trip with Sammy Hagar brings you never- AXS TV Insider before-seen performances featuring Sammy and various season 2 guests. Featuring highlights and interviews with the biggest names in music. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT 6:50 PM ET / 3:50 PM PT The Big Interview Cat Stevens: A Cat’s Attic Joan Baez - Dan Rather sits down with folk trailblazer and human rights activist Joan Baez to Filmed in London, “A Cat’s Attic” celebrates the illustrious career of one of the most important discuss her music, past loves, and recent decision to step away from the stage. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Farm Security Administation Photographs in Indiana

FARM SECURITY ADMINISTRATION PHOTOGRAPHS IN INDIANA A STUDY GUIDE Roy Stryker Told the FSA Photographers “Show the city people what it is like to live on the farm.” TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 The FSA - OWI Photographic Collection at the Library of Congress 1 Great Depression and Farms 1 Roosevelt and Rural America 2 Creation of the Resettlement Administration 3 Creation of the Farm Security Administration 3 Organization of the FSA 5 Historical Section of the FSA 5 Criticisms of the FSA 8 The Indiana FSA Photographers 10 The Indiana FSA Photographs 13 City and Town 14 Erosion of the Land 16 River Floods 16 Tenant Farmers 18 Wartime Stories 19 New Deal Communities 19 Photographing Indiana Communities 22 Decatur Homesteads 23 Wabash Farms 23 Deshee Farms 24 Ideal of Agrarian Life 26 Faces and Character 27 Women, Work and the Hearth 28 Houses and Farm Buildings 29 Leisure and Relaxation Activities 30 Afro-Americans 30 The Changing Face of Rural America 31 Introduction This study guide is meant to provide an overall history of the Farm Security Administration and its photographic project in Indiana. It also provides background information, which can be used by students as they carry out the curriculum activities. Along with the curriculum resources, the study guide provides a basis for studying the history of the photos taken in Indiana by the FSA photographers. The FSA - OWI Photographic Collection at the Library of Congress The photographs of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) - Office of War Information (OWI) Photograph Collection at the Library of Congress form a large-scale photographic record of American life between 1935 and 1944. -

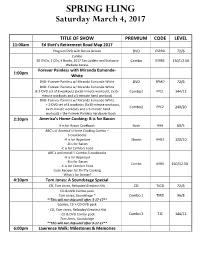

Spring Fling Saturday March 4, 2017

Spring Fling Saturday March 4, 2017 TITLE OF SHOW PREMIUM CODE LEVEL 11:00am Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map 2017 Program DVD with Bonus lecture DVD ESRRD 72/6 Combo -20 DVDs, 2 CDs, 4 Books, 2017 Tax Update and Exclusive Combo ESRRC 150/12.50 Website Access Forever Painless with Miranda Esmonde- 1:00pm White DVD- Forever Painless w/ Miranda Esmonde-White DVD FPMD 72/6 DVD- Forever Painless w/ Miranda Esmonde-White & 2-DVD set of 8 workouts (5x30-minute workouts, 2x15- Combo1 FPC1 144/12 minute workouts and a 5-minute hand workout) DVD- Forever Painless w/ Miranda Esmonde-White + 2-DVD set of 8 workouts (5x30-minute workouts, Combo2 FPC2 240/20 2x15-minute workouts and a 5-minute hand workout) + the Forever Painless hardcover book 2:30pm America’s Home CooKing: B is for Bacon B is for Bacon Cookbook Book AHB 60/5 ABC’s of America’s Home Cooking Combo – 3 Cookbooks -A is for AppetiZerE 3books AHB3 120/10 Eamonn McCrystal-B is for Bacon -C is for Comfort Food ABC’s and more!!! Combo-5 cookbooks -A is for AppetiZer -B is for Bacon Combo AHB5 150/12.50 -C is for Comfort Food -Easy Recipes for Thrifty Cooking -What’s for Dinner? 4:30pm Tom Jones: A Soundstage Special CD, Tom Jones, Reloaded Greatest Hits CD TJCD 72/6 CD & DVD Combo pack Tom Jones, Soundstage * Combo 1 TJRD 96/8 **This will not ship until after 3-17-17** Combo, CD + CD-DVD pack - CD, Tom Jones, Reloaded Greatest Hits - CD & DVD Combo pack Combo 2 TJC 144/12 Tom Jones, Soundstage **This will not ship until after 3-17-17** 6:00pm Lawrence Welk: Milestones & Memories Spring Fling -

Willie Nelson and the Dirt Behind the 'Country Image'

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 17, Number 7, February 9, 1990 Willie Nelson and the dirt behind the 'Country image' by MarCia Merry Carter knew nothing about this and would not have condoned it-was pointing out to me the sights and the WUUe:An Autobiography layout of how the streets run in Washington. by Willie Nelson and Bud Shrake "That string of lights is Pennsylvania Avenue," my Pocket Books, New York, 1989 companion would say between drags on the joint and 334 pages, paperbound, $4.95 swallows of beer. .It was a good way to soak up a geography lesson, laid back on the roof of the White House.Nobody from the Secret Service was watching us-orif they were, it was with the intention of keeping Country:The Music andthe Musicians us out of trouble instead of getting us into it. .. I The Country Music Foundation guess the roof of the White House is the safest place I Abbeville Press, Inc., New York, 1988 can think of to smoke dope. 595 pages, illus., hardbound, $65 Hell, it had only been a couple of days ago that I was busted and locked in jail in the Bahamas for a handful of weed that I never even had a chance to set As of year-end 1989, you could still find the book Willie, the on fire.. .. autobiography of Willie Nelson, on the rack in the paper Marijuana is like sex.If I don't do it everyday, I backs section of most big supermarkets. To save yourself get a headache. -

“A Heart of Gold” Neil Young to Be Honoured with the 2011 Allan Waters Humanitarian Award

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE “A HEART OF GOLD” NEIL YOUNG TO BE HONOURED WITH THE 2011 ALLAN WATERS HUMANITARIAN AWARD Toronto, ON (January 26, 2011) – He is one of the most gifted and celebrated singer-songwriters in rock and roll history. The Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (CARAS) and CTV are pleased to announce Neil Young as the recipient of the 2011 Allan Waters Humanitarian Award. The Award, named after CHUM Ltd. founder Allan Waters, is made possible by funding from the CTV-CHUM benefits package. The Allan Waters Humanitarian Award recognizes an outstanding Canadian artist whose humanitarian contributions have positively enhanced the social fabric of Canada. The award will be presented to Mr. Young during CTV’s broadcast of THE 2011 JUNO AWARDS on Sunday, March 27. Nominations will be announced next Tuesday, February 1. The impact of Neil Young’s music as well as his philanthropy has touched millions of lives and spans generations. Young is a five-time JUNO Award winner and was inducted to the Canadian Music Hall of Fame in 1982. In 2009 he was made an Officer of the Order of Canada and in 2010 was named the MusiCares Person of the Year by The National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. ”We are thrilled to salute Neil Young’s committed and compassionate legacy. As a driving force behind one of music’s most successful fundraising events, Farm Aid, and a key participant in Live 8 right here at home, plus many other deserving causes and programs, his tenacity and spirit is highly regarded among his peers and serves as an inspiration to all of us,” said Melanie Berry, President & CEO of CARAS/The JUNO Awards & MusiCounts. -

THE NEW DEAL, RURAL POVERTY, and the SOUTH by CHARLES

THE NEW DEAL, RURAL POVERTY, AND THE SOUTH by CHARLES KENNETH ROBERTS KARI FREDERICKSON, COMMITTEE CHAIR GEORGE C. RABLE LISA LINDQUIST DORR ANDREW J. HUEBNER PETE DANIEL A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2012 Copyright Charles Kenneth Roberts 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the political and administrative history of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) and its predecessors, the New Deal agency most directly associated with eliminating rural poverty. In addition, it studies and describes the efforts to remedy rural poverty, with an emphasis on farm security efforts (particularly rural rehabilitation) in the South, by looking at how the FSA’s actual operating programs (rural rehabilitation, tenant-purchase, and resettlement) functioned. This dissertation demonstrates that it is impossible to understand either element of the FSA’s history – its political and administrative history or the successes and failures of its operating programs – without understanding the other. The important sources include archival collections, congressional records, newspapers, and published reports. This dissertation demonstrates that New Deal liberal thought (and action) about how to best address rural poverty evolved considerably throughout the 1930s. Starting with a wide variety of tactics (including resettlement, community creation, land use reform, and more), by 1937, the New Deal’s approach to rural poverty had settled on the idea of rural rehabilitation, a system of supervised credit and associated ideas that came to profoundly influence the entire FSA program. This proved to be the only significant effort in the New Deal to solve the problems of rural poverty. -

Farm Aid Artists 1985 – 2017

PHOTO CREDIT: PAUL NATKIN Pete Seeger performs with Farm Aid Board Members AUGUST 2018 FARM AID ARTISTS 1985 – 2017 • 40 Points • Mandy Barnett • Tony Caldwell Since 1985, Farm Aid concerts • Acoustic Syndicate • Roseanne Barr • Calhoun Twins have brought together the • The Avett Brothers • The Beach Boys • Campanas de America greatest artists in American • Bryan Adams • Gary Beaty • Glen Campbell music. Of all the concerts for • Kip Addotta • Beck • Mary Chapin Carpenter a cause that began in the mid- • Trace Adkins • Bellamy Brothers • Bill Carter • Alabama • Ray Benson • Carlene Carter 80s, Farm Aid remains the only • Alabama Shakes • Kendra Benward • Deana Carter one that has the unique and • Dr. Buzz Aldrin • Ryan Bingham & the Dead • John Carter Cash unwavering commitment of its • Dennis Alley & The Horses • Johnny Cash original founders. Nearly 500 Wisdom Indian Dancers • Black 47 • June Carter Cash artists have played on the Farm • Greg Allman • Blackhawk • Felix Cavaliere Aid stage to keep family farmers • The Allman Brothers Band • Nina Blackwood • Central Texas Posse on the land and inspire people to • ALO • Blackwood Quartet • Marshall Chapman choose family farm food. • Dave Alvin • The Blasters • Tracy Chapman • Dave Alvin & the • Billy Block • Beth Nielsen Chapman Allnighters • Blue Merle • Charlie Daniels Band PHOTO CREDIT: EBET ROBERTS • David Amram • Grant Boatwright • Kenny Chesney • John Anderson • BoDeans • Mark Chesnutt • Lynn Anderson • Suzy Bogguss • Dick Clark • Arc Angels • Bon Jovi • Guy Clark • Skeet Anglin -

Willie Hugh Nelson Est Né Le 29 Avril 1933 À Abbott, Périphérie De Fort Worth (Texas), Pendant La Grande Dépression

Willie Hugh Nelson est né le 29 avril 1933 à Abbott, périphérie de Fort Worth (Texas), pendant la Grande Dépression. Il sera élevé par ses Grands Parents (ses parents, sa mère Myrle Marie (née Greenhaw et son père Ira Doyle Nelson divorcent alors que Willie n’a que 6 mois). Son grand-père forgeron décèdera lorsque Willie à 6 ans. En dehors de l’école il va travailler dans les champs de coton ou de maïs pour s’acheter des fournitures scolaires. Sa Grand-mère, cantinière, gagne 18 $ par jour et s’occupe de sa famille. Autour de sa 5ème année Willie apprend la musique sur une guitare ’’ Harmony ‘’ que lui achète son grand père, à partir d’un catalogue de vente par correspondance ‘’ Sears and Roebuck ‘’. Sa grand-mère commence à lui montrer quelques accords ; sa sœur Bobbie, aînée de 2 ans, joue du piano. A 7 ans Willie écrit sa première chanson et à 9 ans il chante dans un groupe local, les ‘’Bohemian Polka’’. Après ses études secondaires Willie occupe plusieurs emplois : vendeur d’encyclopédies en faisant du porte-à-porte, puis représentant de machines à coudre Singer. Willie commence à jouer dans des orchestres puis intègre l'US Air Force en 1950. En 1956 Il reprend quelques études à l'université Baylor de Waco, mais abandonne rapidement celles-ci et une future carrière d’agriculteur pour devenir musicien et disc jockey et se destiner à la Country Music. S'installant à Vancouver, dans l'état de Washington, le jeune homme débute dans les clubs, tentant d'imposer son style folk sudiste traditionnel face à un public globalement indifférent à ce genre. -

Cultivate Your Thinking. Start Your Free Trial at Aei.Ag/Premium

Escaping 1980 Episode 4 – Bottoming Out David Widmar: We saw in 1972, they bought as much as they could as quickly as possible so that way no one knew how bad the situation was. Brent Gloy: This changed the tone from the “sky is the limit” to the “sky is falling overnight.” We had people walking into banks and shooting loan officers and bank presidents, because they'd lost their family. David Widmar: Every farm boom ends. It's how it ends that's the difficult part. Sarah Mock: Where the 1970s might've been a little before Brent's time. The 1980s were not. Brent Gloy: I grew up on the farm and, you know, Husker football is a big thing, of course, in Nebraska. So, in 1983, we should have won the national championship that was devastating. I always think of Journey and Van Halen, and that was kind of my era - Guns and Roses toward the end of the 80s. Wall Street – “Greed is good.” I don't remember when that movie came out [in 1987]. The original with Charlie Sheen and Gordon Gekko, “Greed is good.” Sarah Mock: Brent, as is clearly evidenced by the story, has been a documented econ and finance nerd since at least 1987. For the rest of his generation these years were about Ferris Bueller's Day Off and the Breakfast Club, Michael Jackson's We Are the World broadcast at Live Aid, and a lot of spandex, Doc Martins, and heavy metal. Even beyond the cultural milieu, Brent and David also have particular memories from the fallout of the Chernobyl disaster to the ongoing Cold War.