Captain Hook's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Yorker

Kindle Edition, 2015 © The New Yorker COMMENT SEARCH AND RESCUE BY PHILIP GOUREVITCH On the evening of May 22, 1988, a hundred and ten Vietnamese men, women, and children huddled aboard a leaky forty-five-foot junk bound for Malaysia. For the price of an ounce of gold each—the traffickers’ fee for orchestrating the escape—they became boat people, joining the million or so others who had taken their chances on the South China Sea to flee Vietnam after the Communist takeover. No one knows how many of them died, but estimates rose as high as one in three. The group on the junk were told that their voyage would take four or five days, but on the third day the engine quit working. For the next two weeks, they drifted, while dozens of ships passed them by. They ran out of food and potable water, and some of them died. Then an American warship appeared, the U.S.S. Dubuque, under the command of Captain Alexander Balian, who stopped to inspect the boat and to give its occupants tinned meat, water, and a map. The rations didn’t last long. The nearest land was the Philippines, more than two hundred miles away, and it took eighteen days to get there. By then, only fifty-two of the boat people were left alive to tell how they had made it—by eating their dead shipmates. It was an extraordinary story, and it had an extraordinary consequence: Captain Balian, a much decorated Vietnam War veteran, was relieved of his command and court- martialled, for failing to offer adequate assistance to the passengers. -

Facultad De Filosofía Y Letras Título Del

CURSO 2018-2019 Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Grado en Periodismo Título del TFG LA PERSONALIDAD DEL PETER PAN ORIGINAL EN LA LITERATURA Y LA CONCEPCIÓN SIMPLIFICADA DEL PERSONAJE EN EL IMAGINARIO COLECTIVO Alumno: Juan Eguren Paredes Tutora: Nereida López Vidales 1 2 RESUMEN Arrastrados por la cultura multimedia, generaciones enteras han disfrutado y mitificado iconos de la gran pantalla sin conocer las verdaderas intenciones de su autor original. Peter Pan es un ejemplo de ello y su personalidad fue fruto de su época, en el Londres de principios del siglo XX. Sus rasgos influenciados por personajes mitológicos y experiencias de su creador, James M. Barrie, se perdieron con la adaptación que lo hizo mundialmente famoso. Disney le dio el éxito y blanqueó aspectos de Pan que, aun así, han trascendido al imaginario colectivo llegando a considerar a “Peter Pan” como un adulto que no quiere afrontar responsabilidades. Este estudio pretende analizar la personalidad escogida por Barrie así como sus diferentes obras con él como protagonista y el poso cultural restante a día de hoy pasando por el “síndrome” tan frecuentemente mencionado. Esto supondrá no sólo el análisis de las tres obras escritas por el escocés que le mencionan explícitamente, sino también la contextualización de Neverland o El País de Nunca Jamás, la descripción de un “Peter Pan” hoy en día, tal y como lo presentan estudios en psicología, y un resumen final como comparativa de las diferentes cualidades atribuidas al personaje. Además, se incluirán algunas referencias a alguna adaptación cinematográfica y la historia que llevó a Barrie al diseño del personaje tal y como se puede disfrutar en su literatura. -

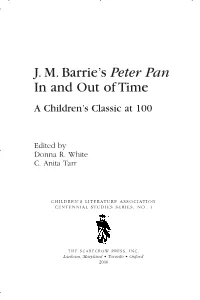

J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan in and out of Time

06-063 01 Front.qxd 3/1/06 7:36 AM Page iii J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan In and Out of Time A Children’s Classic at 100 Edited by Donna R. White C. Anita Tarr CHILDREN’S LITERATURE ASSOCIATION CENTENNIAL STUDIES SERIES, NO. 4 THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Oxford 2006 06-063 01 Front.qxd 3/1/06 7:36 AM Page v Contents Introduction vii Donna R. White and C. Anita Tarr Part I: In His Own Time 1 Child-Hating: Peter Pan in the Context of Victorian Hatred 3 Karen Coats 2 The Time of His Life: Peter Pan and the Decadent Nineties 23 Paul Fox 3 Babes in Boy-Land: J. M. Barrie and the Edwardian Girl 47 Christine Roth 4 James Barrie’s Pirates: Peter Pan’s Place in Pirate History and Lore 69 Jill P. May 5 More Darkly down the Left Arm: The Duplicity of Fairyland in the Plays of J. M. Barrie 79 Kayla McKinney Wiggins Part II: In and Out of Time—Peter Pan in America 6 Problematizing Piccaninnies, or How J. M. Barrie Uses Graphemes to Counter Racism in Peter Pan 107 Clay Kinchen Smith v 06-063 01 Front.qxd 3/1/06 7:36 AM Page vi vi Contents 7 The Birth of a Lost Boy: Traces of J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan in Willa Cather’s The Professor’s House 127 Rosanna West Walker Part III: Timelessness and Timeliness of Peter Pan 8 The Pang of Stone Words 155 Irene Hsiao 9 Playing in Neverland: Peter Pan Video Game Revisions 173 Cathlena Martin and Laurie Taylor 10 The Riddle of His Being: An Exploration of Peter Pan’s Perpetually Altering State 195 Karen McGavock 11 Getting Peter’s Goat: Hybridity, Androgyny, and Terror in Peter Pan 217 Carrie Wasinger 12 Peter Pan, Pullman, and Potter: Anxieties of Growing Up 237 John Pennington 13 The Blot of Peter Pan 263 David Rudd Part IV: Women’s Time 14 The Kiss: Female Sexuality and Power in J. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

Study Guide for Educators

Study Guide for Educators A Musical Based on the Play by Sir James M. Barrie Music by Mark Charlap Additional Music by Jule Styne Lyrics by Carolyn Leigh Additional Lyrics by Betty Comden and Adolph Green Originally Adapted and Directed by Jerome Robbins 1 This production of Peter Pan is generously sponsored by: Ng & Ng Dental and Eye Care Joan Gellert-Sargen Jerry & Sharon Melson Ron Tindall, RN Welcome to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre A NOTE TO THE TEACHER Thank you for bringing your students to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre at Allan Hancock College. Here are some helpful hints for your visit to the Marian Theatre. The top priority of our staff is to provide an enjoyable day of live theatre for you and your students. We offer you this study guide as a tool to prepare your students prior to the performance. SUGGESTIONS FOR STUDENT ETIQUETTE Note-able behavior is a vital part of theater for youth. Going to the theater is not a casual event. It is a special occasion. If students are prepared properly, it will be a memorable, educational experience they will remember for years. 1. Have students enter the theater in a single file. Chaperones should be one adult for every ten students. Our ushers will assist you with locating your seats. Please wait until the usher has seated your party before any rearranging of seats to avoid injury and confusion. While seated, teachers should space themselves so they are visible, between every groups of ten students. Teachers and adults must remain with their group during the entire performance. -

Playful Subversions: Hollywood Pirates Plunder Spanish America NINA GERASSI-NAVARRO

Playful Subversions: Hollywood Pirates Plunder Spanish America NINA GERASSI-NAVARRO The figure of the pirate evokes a number of distinct and contrasting images: from a fearless daredevil seeking adventure on the high seas to a dangerous and cruel plunderer moved by greed. Owing obedience to no one and loyal only to those sharing his way of life, the pirate knows no limits other than the sea and respects no laws other than his own. His portrait is both fascinating and frightening. As a hero, he is independent, audacious, intrepid and rebellious. Defying society's rules and authority, sailing off to the unknown in search of treasures, fearing nothing, the pirate is the ultimate symbol of freedom. But he is also a dangerous outlaw, known for his violent tactics and ruthless assaults. The social code he lives by inspires enormous fear, for it is extremely rigid and anyone daring to disobey the rules will suffer severe punishments. These polarized images have captured the imagination of historians and fiction writers alike. Sword in hand, eye-patch, with a hyperbolic mustache and lascivious smile, Captain Hook is perhaps the most obvious image-though burlesque- of the dangerous fictional pirate. His greedy hook destroys everything that crosses his hungry path, even children. On a more serious level, we might think of the tortures the cruel and violent Captain Morgan inflicted upon his enemies, hanging them by their testicles, cutting their ears or tongues off; or of Jean David Nau, the French pirate known as L 'Ollonais (el Olonés in Spanish), who would rip the heart out of his victims if they did not comply with his requests; 1 or even the terrible Blackbeard who enjoyed locking himself up with a few of his men and shooting at them in the dark: «If I don't kill someone every two or three days I will lose their respect» he is said to have claimed justifyingly. -

Finding Neverland

BARRIE AND THE BOYS 0. BARRIE AND THE BOYS - Story Preface 1. J.M. BARRIE - EARLY LIFE 2. MARY ANSELL BARRIE 3. SYLVIA LLEWELYN DAVIES 4. PETER PAN IS BORN 5. OPENING NIGHT 6. TRAGEDY STRIKES 7. BARRIE AND THE BOYS 8. CHARLES FROHMAN 9. SCENES FROM LIFE 10. THE REST OF THE STORY Barrie and the Llewelyn-Davies boys visited Scourie Lodge, Sutherland—in northwestern Scotland—during August of 1911. In this group image we see Barrie with four of the boys together with their hostess. In the back row: George Llewelyn Davies (age 18), the Duchess of Sutherland and Peter Llewelyn Davies (age 14). In the front row: Nico Llewelyn Davies (age 7), J. M. Barrie (age 51) and Michael Llewelyn Davies (age 11). Online via Andrew Birkin and his J.M. Barrie website. After their mother's death, the five Llewelyn-Davies boys were alone. Who would take them in? Be a parent to them? Provide for their financial needs? Neither side of the family was really able to help. In 1976, Nico recalled the relief with which his uncles and aunts greeted Barrie's offer of assistance: ...none of them [the children's uncles and aunts] could really do anything approaching the amount that this little Scots wizard could do round the corner. He'd got more money than any of us and he's an awfully nice little man. He's a kind man. They all liked him a good deal. And he quite clearly had adored both my father and mother and was very fond of us boys. -

Peter Pan Jr - Full Synopsis Peter Pan and the Other Inhabitants of Neverland Open the Show by Introducing the Audience to Their World ("Neverland")

Peter Pan Jr - Full Synopsis Peter Pan and the other inhabitants of Neverland open the show by introducing the audience to their world ("Neverland"). Meanwhile, in the Darling Nursery ("Prologue"), Wendy, Michael, and John are playing before bed as Mrs.Darling and Mr.Darling get ready to go out. Nana, the family dog, and Liza encourage the children to go to bed. Before leaving, Mrs. Darling sings a lullaby with the children to say goodnight ("Tender Shepherd"). As soon as the parents have gone, Peter follows Tinker Bell into the room, searching for Peter’s shadow. Wendy is awakened by the commotion and quickly befriends the mysterious visitor. The Darling children soon set off to Neverland with Peter, travelling the only way possible ("I’m Flying"). Back in Neverland, the Pirates search for the Lost Boys ("Pirate March"). After discovering the Lost Boys’ underground home, Captain Hook and his first mate Smee devise a plan ("Hook’s Tango"), but is chased away by the Crocodile. The Lost Boys remain in peril as the Brave Girls, led by Tiger Lily, arrive on the scene ("Brave Girl Dance"). Peter and the Darlings reach Neverland, frightening the Brave Girls. Finally safe, the Lost Boys celebrate the arrival of their new “mother” ("Wendy"). Captain Hook’s first attempt to poison the Lost Boys is thwarted by their new guardian, and the pirates must devise a new plan ("Hook’s Tarantella"). The next day, the Lost Boys learn a lesson from Peter, their “father” ("I Won’t Grow Up"). When they discover that the pirates have captured Tiger Lily, the Lost Boys help to free her. -

Disney Junior Jake and the Never Land Pirates Magical Story Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DISNEY JUNIOR JAKE AND THE NEVER LAND PIRATES MAGICAL STORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK none | none | 30 Nov 2012 | Parragon Book Service Ltd | 9781781860366 | English | Bath, United Kingdom Disney Junior Jake and the Never Land Pirates Magical Story PDF Book We know that parent engagement in the media their young children consume can have a very important benefit in terms of learning as well as become a gateway for conversations with children around the storylines and themes that are presented. The series has received generally mixed reviews. Categories :. Jake and the Neverland Pirates Playsets. The launch of Disney Junior in the U. We create the underscore. No Preference. It is a television destination enjoyable for children and parents alike, including older children and siblings already engaged in our content, who we want to feel included in Disney Junior. In Disney Junior will debut as a hour basic cable and satellite channel in the U. PJ Masks Action Figures. A review in Variety called it "part video game, part interactive cartoon, part advertisement for 'Peter Pan' merchandise". Yo ho! Sofia is whisked off to the castle, where she learns what it means to be a real princess, discovering empowering lessons about kindness, forgiveness, generosity, courage and self-respect. All Auction Buy It Now. In this episode, the Princess's rainbow wand has run out of power. Disney Junior. Since forums and fan pages first started buzzing about the new Disney Junior brand, questions have been plentiful and answers not as much. Buying Format see all. Many episodes showcase Jake being a huge fan of Peter Pan. -

Published Version

PUBLISHED VERSION Maggie Tonkin From 'Peter Panic' to proto-modernism: the case of J.M. Barrie Changing the Victorian Subject, 2014 / Tonkin, M., Treagus, M., Seys, M., Crozier De Rosa, S. (ed./s), pp.259-281 © 2014 The Contributors This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This licence allows for the copying, distribution, display and performance of this work for non-commercial purposes providing the work is clearly attributed to the copyright holders. Address all inquiries to the Director at the above address. PERMISSIONS http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ http://hdl.handle.net/2440/84284 13 From ‘Peter Panic’ to proto-Modernism: the case of J.M. Barrie Maggie Tonkin The author may be dead as far as Roland Barthes is concerned, but the news is yet to hit the street. Probably nothing speaks more loudly of the gap between academic literary criticism and the culture of reading outside the academy than the latter’s continuing obsession with the author. Barthes’s claim that the author is neither the originator nor the final determiner of textual meaning has assumed the status of orthodoxy in scholarly poetics. Whilst the early austerity has faded somewhat, such that discussion of the historical specificity of the author is no longer scorned in literary studies, the Romantic privileging of the author as the ‘fully intentional, fully sentient source of the literary text, as authority for and limitation on the “proliferating” meanings of the text’, as Andrew Bennett puts it (55), has never regained its former currency. -

Tracy Wells Big Dog Publishing

Tracy Wells Adapted from the 1911 novel by J.M. Barrie Illustration by Alice B. Woodward Big Dog Publishing Peter Pan and Wendy 2 Copyright © 2013, Tracy Wells ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Peter Pan and Wendy is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and all of the countries covered by the Universal Copyright Convention and countries with which the United States has bilateral copyright relations including Canada, Mexico, Australia, and all nations of the United Kingdom. Copying or reproducing all or any part of this book in any manner is strictly forbidden by law. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or videotaping without written permission from the publisher. A royalty is due for every performance of this play whether admission is charged or not. A “performance” is any presentation in which an audience of any size is admitted. The name of the author must appear on all programs, printing, and advertising for the play and must also contain the following notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Big Dog/Norman Maine Publishing LLC, Rapid City, SD.” All rights including professional, amateur, radio broadcasting, television, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved by Big Dog/Norman Maine Publishing LLC, www.BigDogPlays.com, to whom all inquiries should be addressed. Big Dog Publishing P.O. Box 1401 Rapid City, SD 57709 Peter Pan and Wendy 3 For my children. -

Edition 4 | 2019-2020

Our 5-star rated nursing and rehab center delivers a recovery experience that will be remembered for the warmth we exude and the clinical excellence we provide. COME SEE OUR MILLION DOLLAR RENOVATION OF OUR ENTIRE FACILITY ONLY 5-STAR CMS RATED SKILLED NURSING & REHAB FACILITY IN WATERBURY 2019–2020 SEASON Letter from the Chairman 7 Letter from the CEO 9 Jersey Boys 12 Finding Neverland 26 Palace Theater Staff Directory 39 Program information for tonight’s presentation inside. The Palace would like to thank all of its Program advertisers for their support. ADVERTISING Onstage Publications Advertising Department 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 e-mail: [email protected] www.onstagepublications.com This program is published in association with Onstage Publications, 1612 Prosser Avenue, Dayton, Ohio 45409. This program may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher. Onstage Publications is a division of Just Business, Inc. Contents ©2020. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. 4 palace theater letter from the chairman n my role as Chairman of the Board of the Palace Theater, I I have the pleasure of presiding over this beautiful and valued performing arts center and watching it grow each year. This year is particularly exciting, as it is our 15th Anniversary year! Fifteen years ago, a group of dedicated local and state leaders organized to restore and reopen this historic facility. After an extensive renovation, we welcomed our first audience to take in the visual splendors of the theater—and the mellifluous tones of Tony Bennett’s voice.