Guardianship of the Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Basics of the Muslim's Prayer

The Basics of the Muslim’s Prayer Darulmashari^ For Printing, Publishing and Distribution 1st Edition 1423-2002 Contents 1 ............................................................................ The Basics of the Muslim’s Prayer 1 ................................. Darulmashari^ For Printing, Publishing and Distribution 3 ......................................................................................................... Introduction 3 .............................................................. Chapter 1: Preparations Before Praying 4 ........................................................................................ Taharah (Purification) 4 ................................................................ Removal of Najas (Filthy substances) 4 ................................................................................................ Wudu' (Ablution) 5 ...................................................................................... How to Perform Wudu’ 7 ................................................................................................................... Benefit 8 ......................................................................................... Invalidators of Wudu' 8 ............................................................................................ Ghusl (Full Shower) 8 ........................................................................................ How to Perform Ghusl 9 .......................................................................... Tayammum (Dry Purification) -

Prayer and Science (Research on the Main Prayer Movement)

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 9 , No. 11, November, 2019, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2019 HRMARS Prayer and Science (Research on the Main Prayer Movement) Siti Suhailah Binti Hamdan, Wan Khairul Aiman Wan Mokhtar, Mohd Mustaffami Imas To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i11/6581 DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i11/6581 Received: 25 September 2019, Revised: 21 October 2019, Accepted: 01 November 2019 Published Online: 24 November 2019 In-Text Citation: (Hamdan, Mokhtar, Imas, 2019) To Cite this Article: Hamdan, S. S. B., Mokhtar, W. K. A. W., Imas, M. M. (2019). Prayer and Science (Research on the Main Prayer Movement). International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(11), 607–614. Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 9, No. 11, 2019, Pg. 607 - 614 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 607 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 9 , No. 11, November, 2019, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2019 HRMARS Prayer and Science (Research on the Main Prayer Movement) Siti Suhailah Binti Hamdan, Wan Khairul Aiman Wan Mokhtar, Mohd Mustaffami Imas Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA), Gong Badak Campus, 21300, Kuala Nerus, Terengganu, Malaysia Abstract Prayer is very important, special and unique for Muslims. -

Studi Komparasi Tentang Pemahaman Hadis-Hadis Tawassul Menurut Nahdlatul Ulama' Dan Wahabi

STUDI KOMPARASI TENTANG PEMAHAMAN HADIS-HADIS TAWASSUL MENURUT NAHDLATUL ULAMA’ DAN WAHABI TESIS Diajukan untuk Memenuhi Sebagian Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Magister dalam Program Studi Ilmu Hadis Oleh M. Ja’far Asshodiq NIM. F0.8.21.41.04 PASCASARJANA UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI SUNAN AMPEL SURABAYA 2018 ABSTRAK “STUDI KOMPARASI TENTANG PEMAHAMAN HADIS-HADIS TAWASSUL MENURUT NAHDLATUL ULAMA’ DAN WAHABI”, THESIS Pascasarjana UIN Sunan Ampel Surabaya, 2018. Problematika yang diangkat dalam penelitian ini adalah tentang pemahaman hadis-hadis tawassul menurut nahdlatul ulama’ dan wahabi, lantaran tradisi tawassul sudah menjadi tradisi bahkan budaya yang berkembang di belahan dunia utamanya di Indonesia. Secara spesifik kajian ini akan membahas tentang bagaimana pemahaman hadis-hadis tawassul pespektif NU dan wahabi, kemudian membandingkan keduanya serta bagaimana implikasinya. Penelitian ini adalah kajian pustaka atas pemahaman hadis-hadis tawassul menurut NU dan wahabi yang dikaji dengan metode kualitatif, dan dianalisa dengan menggunakan teknik analisis isi (content analysis) yaitu dengan membuat kesimpulan tentang pemahaman hadis-hadis tawassul menurut NU dan wahabi dari premis-premis umum (deduksi) dan data faktual (induksi) secara objektif dan sistematis dengan mengidentifikasi karakteristik spesifikasinya dari pesan-pesan yang termuat dalam karya-karya para tokoh NU dan wahabi yang dilakukan menggunakan pendekatan sosio-historis. Hasil penelitian mengungkap bahwa Pemahaman hadis-hadis tawassul menurut NU terdapat empat macam yaitu; a) bertawassul dengan asma>’ al- h}usna>; b) bertawassul dengan amal sholeh; c) bertawassul dengan orang sholeh yang masih hidup; d) bertawassul dengan orang sholeh yang sudah wafat. Dan pemahaman hadis-hadis tawassul menurut Wahabi ada tiga macam yaitu; a) bertawassul dengan asma>’ al-h}usna>; b) bertawassul dengan amal sholeh; c) bertawassul dengan doa orang sholeh yang masih hidup. -

Prayer for Young and New Muslims

Prayer For Young and New Muslims Imam Yahya M. Al-Hussein 2 Prayer For Young and New Muslims By Imam Yahya M. Al-Hussein Published by: The Islamic Foundation of Ireland 163, South Circular Road, Dublin 8, Ireland. Tel. 01-4533242 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.islaminireland.com 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 7 CHAPTER ONE: PREPARATION FOR THE PRAYER–STAGE 1 9 1.1. THE PRE-CONDITIONS OF PRAYER 11 1.2. WUDU -ABLUTION 12 1.3. THINGS THAT BREAK WUDU -ABLUTION 14 CHAPTER TWO : PRAYER – STAGE 1 2.1. NAMES AND RAK'ATS OF PRAYERS 17 2.2. TIMES OF PRAYER 18 2.3. IQAMAH 20 2.4. SHORT SURAS (QUR’ANIC CHAPTERS) FOR PRAYER 21 2.5. AT-TASHAHUD 24 2.6. HOW THE PRAYER IS PERFORMED 25 2.7. HOW THE FIVE DAILY PRAYERS ARE PERFORMED 28 CHAPTER THREE: PREPARATION FOR THE PRAYER – STAGE 2 3.1. TYPES OF WATER 33 3.2. GHUSL 35 3.3. TAYAMMUM 38 3.4. WIPING OVER THE SOCKS 40 3.5. RULES OF THE TOILET ROOM 42 CHAPTER FOUR : PRAYER – STAGE 2 4.1. AS-SALATU 'ALA AN-NABBI 45 4.2. FARD ACTS OF THE PRAYER 46 5 4.3. SUNNAH ACTS OF THE PRAYER 47 4.4. DHIKR AND DU'AS AFTER SALAM (END OF PRAYER) 49 4.5. DISLIKED ACTS DURING THE PRAYER 50 4.6. THINGS THAT BREAK THE PRAYER 51 4.7. FORBIDDEN TIMES FOR PRAYER 52 4.8. THE PRAYER OF A TRAVELLER 54 4.9. SUJUD AS-SAHW (PROSTRATION OF FORGETFULNESS) 57 4.10. -

Prayer, Come to Success َح َّي َعلَى ال َّصَلة، َح َّي َعلَى اْلفَََلح

ِ ِ ِ َِِّ ِِ َحافظُوا َعلَى ال َّصلََوات َوال َّصََلة اْلُو ْسطَى َوقُوُموا لله قَانت ني ََ )سورة البقرة 238( Come to Prayer, Come to Success َح َّي َعلَى ال َّصَلة، َح َّي َعلَى اْلفَََلح Written by: Dr. Maulana Mohammad Najeeb Qasmi Edited by: Adnan Mahmood Usmani www.najeebqasmi.com i © All rights reserved Come to Prayer, Come to Success َح َّي َع َلى ال َّصﻻة، َح َّي َع َلى ا ْل َف َﻻح By Dr. Muhammad Najeeb Qasmi Edited by: Adnan Mahmood Usmani, Researcher, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Website http://www.najeebqasmi.com/ Facebook MNajeeb Qasmi YouTube Najeeb Qasmi Email [email protected] WhatsApp +966508237446 First Urdu Edition: December 2005 Second Urdu Edition: June 2007 Third Urdu Edition: September 2011 First English Edition: March 2016 Published by: Freedom Fighter Maulana Ismail Sambhali Welfare Society, Deepa Sarai, Sambhal, UP, India Address for Gratis Distribution: Dr. Muhammad Mujeeb, Deepa Sarai, P.O. Sambhal, UP (Pin Code 2044302) India ii Contents Preface .................................................................................. ix Foreword ............................................................................... xi Reflections ........................................................................xiii Reflections ........................................................................ xv Reflections ....................................................................... xvii 1. Importance of Salah (Prayer) ............................................ 1 Verses from the Holy Qur’an -

Fiqh-Of-Salah-Notes-Madinatayn.Pdf

COURSE NOTES All that is good and correct is from Allah (subhanahu wa-ta‘ala) alone – the compilers are solely responsible for any mistakes and errors. Divine Link – Fiqh of Salah Shaykh Yaser Birjas 2 Bismillah al-Rahman al-Rahim 01 | Introduction Five days before the Prophet (sal Allahu alayhi wa sallam) passed away, he was on his deathbed. When you are on your deathbed and talk, you will be saying the most important things in your life. These are the last moments of you life. Think about that time and imagine that you were told that you would be dying in a few days. As you talk to people, what message would you deliver to people? It would be the most important things to you. The Prophet (sal Allahu alayhi wa sallam) five days before he passed away was suffering from the pains of death, and he was suffering for more than fourteen days. One of the companions came and saw him (sal Allahu alayhi wa sallam) aching so much. He said, “Ya Rasulullah, you are suffering so much pain. Why is that?” He (sal Allahu alayhi wa sallam) said, “I suffer double the pain any of you will suffer.” He said, “Is it because you are getting double reward?” He (sal Allahu alayhi wa sallam) said, “I hope so.” At that time, he (sal Allahu alayhi wa sallam) would feel the pain and cover his face, and then when it would stop, he would uncover his face and say, “La ilaha ilAllah. Death has its agonies and pains.” He used to fall unconscious and recover and fall unconscious and recover. -

The World Federation of Ksimc T a R B I Y

TARBIYAH DRAFT THE WORLD FEDERATION OF KSIMC 1 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available fromthe British Library ISBN 978 1 9092851 8 7 © Copyright 2013 The World Federation of KSIMC Published by: The World Federation of Khoja Shia Ithna-Asheri Muslim Communities Registered Charity in the UK No. 282303 The World Federation is an NGO in Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) of the United Nations Islamic Centre,Wood Lane, Stanmore, Middlesex, HA7 4LQ United Kingdom www.world-federation.org First Edition 2013 - 3000 Copies All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations quoted in articles or reviews. THE WORLD FEDERATION OF KHOJA SHIA ITHNA-ASHERI MUSLIM COMMUNITIES TARBIYAH DRAFT THE WORLD FEDERATION OF KSIMC 3 Surah al Baqara (2:177) 4 TARBIYAH Contents SECTION A: INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND i. MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT ......................................................................................................... 9 ii. PREAMBLE ........................................................................................................................................... 10 iii. THE MCE CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT TEAM ................................................................................ 13 -

"Qabli" and "Baadi" in Salaat

Explanation to: "Qabli" and "Baadi" in Salaat As-Salaam 'Alaykum wa Rahmatullaahi wa Barakaatuh. Authubillah Minash-Sheatanirrajeem. Bissmillahi Rahmani Raheem Qabli: Is the SUJUD you make before SALAM when you "Mistakenly Omit Obligatory parts of Salaat". Baadi: Is the SUJUD you make after SALAM when you "mistakenly ADD during salaat". During salaat one may make a mistake and ADD something to his or her salaat or OMIT something in salaat. These two mistakes often confuse us on how to compensate for them. We need to understand the two terms because they are very important to complete our salaat properly. When you add anything: "like Rakaat, Sujuud etc in Salaat which makes the Salaat more than expected, we term it BAADI. To compensate for it, "You will add two sujuud after final Tashahhud and Tasleem then sit down to repeat tashahhud and Tasleem to complete your salaat". On the other hand, when you noticed you've shortened or omitted something in your salaat then compensate with QABLI. It is compensated with two sujuud after the final Tashahhud before final Tasleem". If you are wondering about omitting something whiles reciting Tashahhud then just do Qabli and try to increase your Sunnah salaat or Naflat salaat to help fix any unknown mistakes to your fard prayers. Note: Tashahhud is the ''Attahiiyaat to end'' and Tasleem is the final ''Assalaamu Alaikum Warahmatullah* we say by turning our head to the right then to the left''. May Allah keep guiding us alright and may He forgive our mistakes, Amin. . -

Crown Paper 2 July 2009

Brandeis University Crown Center for Middle East Studies Crown Paper 2 July 2009 From Visiting Graves to Their Destruction The Question of Ziyara through the Eyes of Salafis Ondrej Beranek and Pavel Tupek Crown Papers Editor Naghmeh Sohrabi Consulting Editor Robert L. Cohen Production Manager Benjamin Rostoker Editorial Board Abbas Milani Stanford University Marcus Noland Peterson Institute for International Economics William B. Quandt University of Virginia Philip Robins Oxford University Yezid Sayigh King’s College London Dror Ze’evi Ben Gurion University About the Crown Paper Series These article-length monographs provide a platform for Crown Center faculty, research staff and postdoctroal fellows to publish their long-term research in a peer-reviewed format. The opinions and findings expressed in these papers are those of the authors exclusively, and do not reflect the official positions or policies of the Crown Center for Middle East Studies or Brandeis University. Acknowledgement The authors wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, and Robert Cohen for his impeccable copy editing. Copyright © 2009 Crown Center for Middle East Studies, Brandeis University. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Contemporary Destruction of Graves and Its Legalization 3 Changing Views since Muhammad 6 Ibn Taymiyya and His Times 9 Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab and His Legacy 17 Visiting Graves and Its Implications for Islam: What Is the Connection? 24 About the Authors 35 1 Introduction A RESPECT FOR THE TERR A IN OF DE A TH , A LONG WITH THE INDIVIDU A L GR A VE SITE , SEEMS TO BE ONE OF THE CONTINUITIES OF HUM A N L A NDSC A PE A ND CULTURE , THOUGH THERE H A VE BEEN MONSTROUS EXCEPTIONS ON OCC A SION ...1 In a collection of fatwas, religious opinions, issued by a group of prominent Saudi legal scholars (ulama), we find the following question: “I live in a neighborhood that has a graveyard, and every day I walk along a path that passes beside it. -

The Independent

Support us Contribute Subscribe NEWS INDEPENDENT TV CLIMATE US POLITICS COVID-19 ADVICE FOOTBALL VOICES CULTURE PREMIUM INDY/LIFE INDYBEST INDY100 VOUCHERS Independent Premium > Long Reads Can we solve football’s hate problem? Take a look at the ‘Salah Effect’ When Mo Salah joined Liverpool, Merseyside saw a big fall in the hate-crime rate and a 50 per cent drop in anti-Muslim tweets posted by fans. What can we learn from this, asks Matthew Williams 15 hours ago | 1 comments ollowing the Liverpool-Manchester United game on 15 October 2011, Luis Suarez was accused of racially abusing Patrice Evra. F Despite both player and club maintaining his innocence, Suarez was found guilty by the FA and was punished with an eight- match ban and a £40,000 fine. Regardless of whether it was an intercultural misunderstanding or racism, 10 Liverpool’s unflinching defence of their star striker, especially after the FA’s decision, risked sending the wrong message to fans. During pre-match A no room for racism logo is seen on the shirt of Ademola Lookman civilities at their next meeting in January, Suarez refused to shake the hand (Getty) of Evra. As the game unfolded, a fan was caught on camera making monkey gestures, and at Evra’s every touch of the ball, a chorus of abuse reverberated around the stands of Anfield. A month before the game, I had begun an academic project on measuring online racial tensions. The Suarez-Evra incident soon became its focus. While not well documented in the press at the time, my team found Liverpool fans became increasingly hateful and abusive towards Evra on Twitter and last year, Evra revealed that the racism and death threats he received after the incident resulted in him hiring security at his home. -

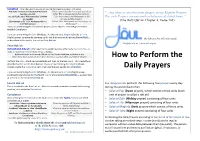

How to Perform the Daily Prayers.Pdf

Tashahhud : After the second prostration resume the kneeling position, and recite: Ash hadu al laa ilaaha illallaahu wahdahu I bear witness that there is no god apart from laa shareeka lah, Allah, Who is unique and without partners. “…but when ye are free from danger, set up Regular Prayers: wa ash hadu anna Muhammadan `abduhu I also bear witness that Muhammad is His For such Prayers are enjoined on believers at stated times.” wa rasuluh servant and His Prophet. Allaahumma salli `alaa Muhammadin wa O God, bless Muhammad and the progeny of (The Holy Qur'an: Chapter 4, Verse 103) Aali Muhammad Muhammad. If you are performing the Fajr (Dawn) prayer, please skip the rest and go to section entitled Completion. If you are performing the Zuhr (Midday), `Asr (Afternoon), Maghrib (Dusk), or `Isha (Night) prayer, continue by standing up for the third unit while reciting Bihawlillahi…. the library for all your needs as described at the end of the section First Rak`ah. [email protected] | www.qul.org.au Third Rak`ah At-Tasbihat al-Arba`ah : After regaining the upright posture, either recite Surat al-Fatiha, or recite al-Tasbihat al-Arba`ah three times, as follows: Subhaanallaahi wa’l hamdu lillaahi wa laa ilaaha illallaahu wallaahu akbar Glory be to God, and praise be to God; there is no god but Allah, and Allah is Greater How to Perform the Perform the ruku`, stand up momentarily and then do the two sujud. This is exactly as described under section First Rak`ah. If you are performing the Maghrib (Dusk) prayers, recite the Tashahhud next. -

The Positioning of Sayyidah Aisha's R.A. Views As the Qaul Mu'tamad Of

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2017, Vol. 7, No. 9 ISSN: 2222-6990 The Positioning of Sayyidah Aisha’s R.A. Views as the Qaul Mu'tamad of Syafi'i Mazhab in Issues related to Solah Syed Sultan Bee bt. Packeer Mohamed School of Languages, Civilization and Philosophy, College of Arts and Sciences, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 Sintok, Kedah *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i9/3349 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i9/3349 ABSTRACT This qualitative study is conducted to identify the extent to which Sayyidah Aisha’s r.a. views have been the qaul mu’tamad of the Shafi’i mazhab scholars regarding solah issues. Simultaneously, it is an effort to investigate how far the views are being practiced among the society these days. Comparative technique was used to compare between Sayyidah Aisha’s r.a. views and those of the Shafi’i mazhab scholars. Inductive technique was then used to analyse the collected data and come up with conclusion. 30 issues were analysed and the findings indicate that there are 21 issues (70%) which took into consideration on Sayyidah Aisha’s r.a. views to become the qaul mu’tamad of Shafi’i mazhab. On the other hand, her views on 3 issues (10%) are supported in certain scenarios and had been the qaul mu’tamad for that particular situations only. In addition, the findings also reveal that Sayyidah Aisha’s r.a. views had not been the qaul mu’tamad of Shafi’i mazhab for only 6 issues (20%).