Mending a Megabat P8 Amphibian Alarm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Are Mouse Lemurs? in the WILD in CAPTIVITY

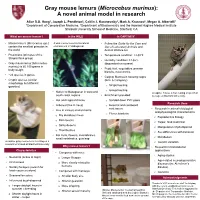

Gray mouse lemurs (Microcebus murinus): A novel animal model in research Alice S.O. Hong¹, Jozeph L. Pendleton², Caitlin J. Karanewsky², Mark A. Krasnow², Megan A. Albertelli¹ ¹Department of Comparative Medicine, ²Department of Biochemistry and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA What are mouse lemurs? In the WILD In CAPTIVITY • Mouse lemurs (Microcebus spp.) A wild mouse lemur in its natural • Follow the Guide for the Care and contain the smallest primates in environment in Madagascar. Use of Laboratory Animals and the world Animal Welfare Act • Prosimians (primates of the • Temperature condition: 74-80ºF Strepsirrhine group) • Humidity condition: 44-65% • Gray mouse lemur (Microcebus (dependent on season) murinus) is 80-100 grams in body weight. • Food: fruit, vegetables, primate biscuits, meal worms • ~24 species in genus • Caging: Marmoset housing cages • Cryptic species (similar (Britz & Company) morphology but different o genetics) Single housing o Group housing • Native to Madagascar in west and A captive mouse lemur resting on perch in south coast regions • Enrichment provided: its cage at Stanford University. • Hot and tropical climate o Sanded down PVC pipes Research Uses • Arboreal (live in trees) o External and cardboard nest boxes • Research in animal’s biological • Live in various environments: and physiological characteristics o Fleece blankets o Dry deciduous trees o Reproductive biology o Rain forests o Torpor, food restriction o Spiny deserts o Manipulation of photoperiod o Thornbushes o Sex differences with behavior • Eat fruits, flowers, invertebrates, o Metabolism small vertebrates, gum/sap A captive gray mouse lemur resting on a o Genetic variation researcher’s hand at Stanford University. -

Lemurs, Monkeys & Apes, Oh

Lemurs, Monkeys & Apes, Oh My! Audience Activity is designed for ages 12 and up Goal Students will be able to understand the differences between primate groups Objective • To use critical thinking skills to identify different primate groups • To learn what makes primates so unique. Conservation Message Many of the world’s primates live in habitats that are currently being threatened by human activities. Most of these species live in rainforests in Asia, South America and Africa, all these places share a similar threat; unstainable agriculture and climate change. In the last 20 years, chimpanzee and ring-tailed lemur populations have declined by 90%. There are some easy things we can do to help these animals! Buying sustainable wood and paper products, recycling any items you can, spreading the word about the issues and supporting local zoos and aquariums. Background Information There are over 300 species of primates. Primates are an extremely diverse group of animals and cover everything from marmosets to lorises to gorillas and chimpanzees. Many people believe that all primates are monkeys, however, this is incorrect. There are many differences between primate species. Primates are broken into prosimians (lemurs, tarsius, bushbabies and lorises), monkeys (Old and New World) and apes (gibbons, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos). Prosimians are primarily tree-dwellers. This group includes species such as lemurs, tarsius, bushbabies and lorises. They have longer snouts than other primates, a wet nose and a good sense of smell. They have smaller brains, large eyes that are adapted for night vision, and long tails that are not prehensile, meaning they are not able to grab onto items with their tails. -

Taxonomic Revision of Mouse Lemurs (Microcebus) in the Western Portions of Madagascar

International Journal of Primatology, Vol. 21, No. 6, 2000 Taxonomic Revision of Mouse Lemurs (Microcebus) in the Western Portions of Madagascar Rodin M. Rasoloarison,1 Steven M. Goodman,2 and Jo¨ rg U. Ganzhorn3 Received October 28, 1999; revised February 8, 2000; accepted April 17, 2000 The genus Microcebus (mouse lemurs) are the smallest extant primates. Until recently, they were considered to comprise two different species: Microcebus murinus, confined largely to dry forests on the western portion of Madagas- car, and M. rufus, occurring in humid forest formations of eastern Madagas- car. Specimens and recent field observations document rufous individuals in the west. However, the current taxonomy is entangled due to a lack of comparative material to quantify intrapopulation and intraspecific morpho- logical variation. On the basis of recently collected specimens of Microcebus from 12 localities in portions of western Madagascar, from Ankarana in the north to Beza Mahafaly in the south, we present a revision using external, cranial, and dental characters. We recognize seven species of Microcebus from western Madagascar. We name and describe 3 spp., resurrect a pre- viously synonymized species, and amend diagnoses for Microcebus murinus (J. F. Miller, 1777), M. myoxinus Peters, 1852, and M. ravelobensis Zimmer- mann et al., 1998. KEY WORDS: mouse lemurs; Microcebus; taxonomy; revision; new species. 1De´partement de Pale´ontologie et d’Anthropologie Biologique, B.P. 906, Universite´ d’Antana- narivo (101), Madagascar and Deutsches Primantenzentrum, Kellnerweg 4, D-37077 Go¨ t- tingen, Germany. 2To whom correspondence should be addressed at Field Museum of Natural History, Roosevelt Road at Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois 60605, USA and WWF, B.P. -

Lemurs Are a Very Special Group of Primates That Are Only Found on the Island of Madagascar

Lemurs are a very special group of primates that are only found on the island of Madagascar. There are over 100 different species of Lemur, many of them are endangered or critically endangered. Lemurs are found in many different habitats and have many different diets, but most are omnivores, eating mostly plants and some insects. Communicate with Smells Lemurs rely heavily on their sense of smell and leave scent markings to communicate. Male Ring-tailed Lemurs will have stink fights, waving their smelly tails at each other. The Little Rock Zoo supports Lemur Love, an organization that helps to protect these endangered species in the wild! Want to Learn more? Check out these links and activities! Lemur Love and Lemur Conservation Network http://www.lemurlove.org/lemurs.html https://www.lemurconservationnetwork.org/why-lemurs/ National Geographic: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/r/ring-tailed-lemur/ https://www.nationalgeographic.org/media/photo-ark-red-ruffed-lemur/ Other: Nat Geo - Lemurs Roam Free on This Ancient Island: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UjSiq53nJBo Duke Lemur Center: https://lemur.duke.edu/discover/meet-the-lemurs/ring-tailed-lemur/ San Diego Zoo: https://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/lemur Each lemur has a role to play in its ecosystem, an animals role, or job, is called its niche. One of the important jobs that Black and White Ruffed Lemurs do is to pollinate flowers! They go from flower to flower, sipping delicious nectar, and in return they spread the flowers pollen, helping to produce seeds and fruit! Cut out the puzzle pieces to make the picture of the Black and White Ruffed Lemur! . -

Population Analysis & Breeding and Transfer Plan Red Ruffed Lemur

Population Analysis & Breeding and Transfer Plan Red Ruffed Lemur (Varecia rubra) AZA Species Survival Plan® Yellow Program AZA Species Survival Plan® Coordinator Christie Eddie, Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo & Aquarium ([email protected]) AZA Studbook Keeper Mylisa Whipple, Saint Louis Zoo ([email protected]) AZA Adjunct Population Advisor Gina M. Ferrie, Disney’s Animal Kingdom® ([email protected]) 9 February 2017 Executive Summary Species Survival Plan® for Red Ruffed Lemur (Varecia rubra) The current SSP population of red ruffed lemurs is N = 187 animals (104 males; 83 females; 0 unknown sex) at 48 AZA institutions and 4 non-member participating institutions. This Population Analysis and Breeding and Transfer Plan was prepared November 2016 at Disney’s Animal Kingdom®. The last Breeding and Transfer Plan for this species was finalized 8 December 2015. Analyses were based on the North American data of the International Varecia rubra Studbook (current to 30 June 2016) and were performed using PopLink 2.4 and PMx 1.4.20160831. The target population size designated by the Prosimian Taxon Advisory Group 2014 Regional Collection Plan is 225. This population currently qualifies as a Yellow SSP. Genetic diversity in this population is currently 91.61%. When gene diversity falls below 90% of that in the founding population, it is expected that reproduction will be increasingly compromised by, among other factors, lower birth weights and greater infant mortality. Gene diversity in 100 years is projected to be 84.2% (based on current statistics, assuming a target population for projections of 225 and lambda = 1.05). Gene diversity in 10 generations (83 years) is projected to be 85.4%. -

Subfossil Lemurs of Madagascar

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE Subfossil Lemurs of Madagascar LAURIE R. GODFREY, WILLIAM L. JUNGERS, AND DAVID A. BURNEY Madagascar’s living lemurs (order Primates) belong to a radia- on steady, gradual diversifi cation would suggest. We believe tion recently ravaged by extirpation and extinction. There that the latter scenario is more consistent with the fossil are three extinct and fi ve extant families (two with extinct record. members) of lemurs on an island of less than 600,000 km2. The question of how lemurs got to Madagascar is still far This level of familial diversity characterizes no other primate from resolved (Godinot, 2006; Masters et al., 2006; Stevens radiation. The remains of up to 17 species of recently extinct and Heesy, 2006; Tattersall, 2006a, 2006b). It is clear that (or subfossil lemurs) have been found alongside those of still Madagascar (with the Indian plate) separated from Africa extant lemurs at numerous Holocene and late Pleistocene long before primates evolved and that it arrived at its present sites in Madagascar (fi gure 21.1, table 21.1). The closest rela- position relative to Africa by 120–130 Ma (Krause et al., 1997; tives of the lemurs are the lorisiform primates of continental Roos et al., 2004; Masters et al., 2006; Rabinowitz and Woods, Africa and Asia; together with the lemurs, these comprise the 2006). Most scholars favor chance rafting of an ancestral suborder Strepsirrhini. lemur from continental Africa to Madagascar (Krause et al., Most researchers have defended an ancient Gondwanan 1997; Kappeler, 2000; Roos et al., 2004; Rabinowitz and (African or Indo-Madagascan) origin for lemurs. -

Ring-Tailed Lemur • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Lemur Catta

Ring-tailed Lemur • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Lemur catta through human understanding Classification What groups does this organism belong to based on characteristics shared with other organisms? Class: Mammalia (all mammals) Order: Primates (prosimians, monkeys, apes, humans) Family: Lemuridae (lemurs) Genus: Lemur (ring-tailed lemur) Species: catta (ring-tailed lemur) Distribution Where in the world does this species live? Ring-tailed lemurs are found in south and southwest Madagascar. Habitat What kinds of areas does this species live in? They prefer spiny forest, lowland gallery forest, dry scrub, dry deciduous forest and rock canyons. Physical Description How would this animal’s body shape and size be described? • The ring-tailed lemur has a very distinctive bushy tail with thirteen alternating black and white bands. • They are about the size of a house cat with a head and body length of 17 inches (42.5 cm) Their tail is 24 inches long (60cm). They weigh 4 ½ - 5 ½ pounds (2.0 – 2.4kg). • They have gray to rosy brown fun on the back, gray limbs and haunches and dark gray heads and necks. • Their undersides are white and their faces are white with dark triangular eye patches and a black pointed muzzle. Diet What does this species eat? In their historic range: This species of lemur eats fruit, leaves, flowers, bark, sap, large insects and sometimes small vertebrates like chameleons. They will occasionally consume soli to supplement their diet. At the zoo: The troop of lemurs is fed vegetables, greens, starches, a low starch gel, biscuits, and a small amount of dried fruit for training. Predators What eats this species? Their main natural predators are the Madagascar harrier-hawk, Madagascar buzzard and fossas. -

Lemurs of Madagascar – a Strategy for Their

Cover photo: Diademed sifaka (Propithecus diadema), Critically Endangered. (Photo: Russell A. Mittermeier) Back cover photo: Indri (Indri indri), Critically Endangered. (Photo: Russell A. Mittermeier) Lemurs of Madagascar A Strategy for Their Conservation 2013–2016 Edited by Christoph Schwitzer, Russell A. Mittermeier, Nicola Davies, Steig Johnson, Jonah Ratsimbazafy, Josia Razafindramanana, Edward E. Louis Jr., and Serge Rajaobelina Illustrations and layout by Stephen D. Nash IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation Conservation International This publication was supported by the Conservation International/Margot Marsh Biodiversity Foundation Primate Action Fund, the Bristol, Clifton and West of England Zoological Society, Houston Zoo, the Institute for the Conservation of Tropical Environments, and Primate Conservation, Inc. Published by: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation, and Conservation International Copyright: © 2013 IUCN Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Inquiries to the publisher should be directed to the following address: Russell A. Mittermeier, Chair, IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22202, USA Citation: Schwitzer C, Mittermeier RA, Davies N, Johnson S, Ratsimbazafy J, Razafindramanana J, Louis Jr. EE, Rajaobelina S (eds). 2013. Lemurs of Madagascar: A Strategy for Their Conservation 2013–2016. Bristol, UK: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation, and Conservation International. 185 pp. ISBN: 978-1-934151-62-4 Illustrations: © Stephen D. -

Base Compositional Bias and Phylogenetic Analyses: a Test of the ‘‘Flying DNA’’ Hypothesis Ronald A

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Vol. 13, No. 3, December, pp. 408–416, 1998 ARTICLE NO. FY980531 Base Compositional Bias and Phylogenetic Analyses: A Test of the ‘‘Flying DNA’’ Hypothesis Ronald A. Van Den Bussche,*,1 Robert J. Baker,* John P. Huelsenbeck,†,2 and David M. Hillis† *Department of Biological Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409; and †Department of Zoology, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 78712 Received November 11, 1997; revised February 25, 1998 Debate over the origin of bats (Chiroptera) has Phylogenetic methods can produce biased estimates existed since Linnaeus (1758) placed bats within the of phylogeny when base composition varies along dif- order Primates. Even with sophisticated techniques for ferent lineages. Pettigrew (1994, Curr. Biol. 4:277–280) identifying character-state variation and methods for has suggested that base composition bias is respon- estimating phylogenetic relationships, this debate con- sible for the apparent support for the monophyly of tinues (Smith, 1977; Smith and Madkour, 1980; Wibble bats (Chiroptera: megabats and microbats) from sev- and Novacek, 1980; Pettigrew, 1986, 1991a,b; Bennet et eral different nuclear and mitochondrial genes. Petti- al., 1988; Pettigrew et al., 1989; Adkins and Honeycutt, grew’s ‘‘flying DNA’’ hypothesis makes several predic- tions: (1) that metabolic constraints associated with 1991; Baker et al., 1991a,b; Mindell et al., 1991; Thewis- flying result in elevated levels of adenine and thymine sen and Babcock, 1991; Simmons et al., 1991; Ammer- throughout the genome of both megabats and micro- man and Hillis, 1992; Bailey et al., 1992; Stanhope et bats, (2) that the resulting base compositional bias in al., 1992; Simmons, 1994). -

Chitinase Expression in the Stomach of the Aye-Aye (Daubentonia

CHITINASE EXPRESSION IN THE STOMACH OF THE AYE-AYE (DAUBENTONIA MADAGASCARIENSIS). A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Melia G. Romine August 2020 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Melia G. Romine B.S., Kent State University, 2018 M.A., Kent State University, 2020 Approved by _______________________, Advisor Dr. Anthony J. Tosi _______________________, Chair, Department of Anthropology Dr. Mary Ann Raghanti _______________________, Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Dr. Mandy Munro-Stasiuk TABLE OF CONTENTS -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------iii LIST OF FIGURES ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------v LIST OF TABLES -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------vi DEDICATION ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------viii CHAPTERS I. INTRODUCTION ------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 FEEDING STRATEGIES ---------------------------------------------------------------------2 OPTIMAL FOOD SOURCES ----------------------------------------------------------------3 BODY SIZE -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 DAUBENTONIA -

Reconstruction of an Extraordinary Extinct Primate from Madagascar

COMMENTARY Reconstruction of an extraordinary extinct primate from Madagascar Ian Tattersall* Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024 he minicontinent of Madagas- cus and its close relative Archaeolemur car has been separated by 350 have been reported as pronograde ter- miles of ocean from its neigh- restrial quadrupeds (10, 11) (Fig. 1). bor Africa for at least the past These two last genera, and the ex- T120 million years, i.e., since long before tremely short-faced and deep-skulled the beginning of the Age of Mammals Hadropithecus in particular, were also (1). As a result, the island’s flora and exceptional in showing extended dental fauna show extremely elevated levels of development schedules that presumably endemicity overall (2), and its native reflected prolonged overall develop- mammals show a curious combination of mental periods (12); and compared low diversity at the ordinal level with with other members of the Malagasy extraordinarily high diversity at lower lemur fauna (living and extinct), they taxonomic levels (3). Today, for exam- were also highly encephalized (4, 9). Fig. 1. Reconstruction by the artist Stephen Nash ple, Madagascar harbors an astonishing The first subfossil remains of Hadro- of a Hadropithecus individual as it may have ap- 30% of all primate families and some pithecus were recovered at around the peared in life. Pelage coloration and distribution are, of course, conjectural. 21% of all primate genera (3), all of turn of the 20th century from the An- them represented nowhere else. Yet, drahomana cave, near the southern tip high as these figures are, they would of Madagascar. -

Microcebus Griseorufus) Conservation: Local Resource Utilization and Habitat Disturbance at Beza Mahafaly, Sw Madagascar

THE HUMAN FACTOR IN MOUSE LEMUR (MICROCEBUS GRISEORUFUS) CONSERVATION: LOCAL RESOURCE UTILIZATION AND HABITAT DISTURBANCE AT BEZA MAHAFALY, SW MADAGASCAR A Dissertation Presented by EMILIENNE RASOAZANABARY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2011 Anthropology © Copyright by Emilienne Rasoazanabary 2011 All Rights Reserved THE HUMAN FACTOR IN MOUSE LEMUR (MICROCEBUS GRISEORUFUS) CONSERVATION: LOCAL RESOURCE UTILIZATION AND HABITAT DISTURBANCE AT BEZA MAHAFALY, SW MADAGASCAR A Dissertation Presented By EMILIENNE RASOAZANABARY Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________ Laurie R. Godfrey, Chair _______________________________________ Lynnette L. Sievert, Member _______________________________________ Todd K. Fuller, Member ____________________________________ Elizabeth Chilton, Department Head Anthropology This dissertation is dedicated to the late Berthe Rakotosamimanana and Gisèle Ravololonarivo (Both Professors in the DPAB) Claire (Cook at Beza Mahafaly) Pex and Gyca (Both nephews) Guy and Edmond (Both brothers-in-law) Claudia and Alfred (My older sister and my older brother) All of my grandparents Rainilaifiringa (Grandpa) All of the fellow gray mouse lemurs ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation has been more a process than a document; its completion is long anticipated and ever-so-welcome. So many people participated in and brought to me the most precious and profoundly appreciated support – academic, physical, and emotional. I would not have been able to conduct this work without leaning on those people. I am very grateful to every single one of them. In case you read the dissertation and find your name unlisted, just remember that my gratitude extends to each one of you. I am extremely grateful to Dr.