Running Head: FAN PRACTICES and DOCTOR WHO 1 FAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cons & Confusion

Cons & Confusion The almost accurate convention listing of the B.T.C.! We try to list every WHO event, and any SF event near Buffalo. updated: July 19, 2019 to add an SF/DW/Trek/Anime/etc. event; send information to: [email protected] 2019 DATE local EVENT NAME WHERE TYPE WEBSITE LINK JULY 18-21 NYS MISTI CON Doubletree/Hilton, Tarrytown, NY limited size Harry Potter event http://connecticon.org/ JULY 18-21 CA SAN DIEGO COMIC CON S.D. Conv. Ctr, San Diego, CA HUGE media & comics show NO DW GUESTS YET! Neal Adams, Sergio Aragones, David Brin, Greg Bear, Todd McFarlane, Craig Miller, Frank Miller, Audrey Niffenegger, Larry Niven, Wendy & Richard Pini, Kevin Smith, (Jim?) Steranko, J Michael Straczynski, Marv Wolfman, (most big-name media guests added in last two weeks or so) JULY 19-21 OH TROT CON 2019 Crowne Plaza Htl, Columbus, OH My Little Pony' & other equestrials http://trotcon.net/ Foal Papers, Elley-Ray, Katrina Salisbury, Bill Newton, Heather Breckel, Riff Ponies, Pixel Kitties, The Brony Critic, The Traveling Pony Museum JULY 19-21 KY KEN TOKYO CON Lexington Conv. Ctr, Lexington, KY anime & gaming con https://www.kentokyocon.com/ JULY 20 ONT ELMVALE SCI-FI FANTASY STREET PARTY Queen St, Elmvale, Ont (North of Lake Simcoe!) http://www.scififestival.ca/ Stephanie Bardy, Vanya Yount, Loc Nguyen, Christina & Martn Carr Hunger, Julie Campbell, Amanda Giasson JULY 20 PA WEST PA BOOK FEST Mercer High School, Mercer, PA all about books http://www.westpabookfestival.com/ Patricia Miller, Michael Prelee, Linda M Au, Joseph Max Lewis, D R Sanchez, Judy Sharer, Arlon K Stubbe, Ruth Ochs Webster, Robert Woodley, Kimberly Miller JULY 20-21 Buf WILD RENN FEST Hawk Creek Wildlife Ctr, East Aurora, NY Renn fest w/ live animals https://www.hawkcreek.org/wp/ "Immerse yourself in Hawk Creek’s unique renaissance-themed celebration of wildlife diversity! Exciting entertainment and activities for all ages includes live wildlife presentations, bird of prey flight demonstrations, medieval reenactments, educational exhibits, food, music, art, and much more! JULY 20-21 T.O. -

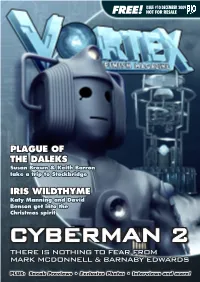

Plague of the Daleks Iris Wildthyme

ISSUE #10 DECEMBER 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE PLAGUE OF THE DALEKS Susan Brown & Keith Barron take a trip to Stockbridge IRIS WILDTHYME Katy Manning and David Benson get into the Christmas spirit CYBERMAN 2 THERE IS NOTHING TO FEAR FROM MARK MCDONNELL & barnaby EDWARDS PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL THE BIG FINISH SALE Hello! This month’s editorial comes to you direct Now, this month, we have Sherlock Holmes: The from Chicago. I know it’s impossible to tell if that’s Death and Life, which has a really surreal quality true, but it is, honest! I’ve just got into my hotel to it. Conan Doyle actually comes to blows with Prices slashed from 1st December 2009 until 9th January 2010 room and before I’m dragged off to meet and his characters. Brilliant stuff by Holmes expert greet lovely fans at the Doctor Who convention and author David Stuart Davies. going on here (Chicago TARDIS, of course), I And as for Rob’s book... well, you may notice on thought I’d better write this. One of the main the back cover that we’ll be launching it to the public reasons we’re here is to promote our Sherlock at an open event on December 19th, at the Corner Holmes range and Rob Shearman’s book Love Store in London, near Covent Garden. The book will Songs for the Shy and Cynical. Have you bought be on sale and Rob will be signing and giving a either of those yet? Come on, there’s no excuse! couple of readings too. -

Web Version Please Subscribe to the Relative Times For

Volume XVI Number 2 November/December 2004 Inside: Fast Forward, Part 3 Blake’s 7 Spinoffs All I Want for Dalekmas MTL’s 15th Anniversary Celebration And More WEB VERSION PLEASE SUBSCRIBE TO THE RELATIVE TIMES FOR THE FULL VERSION Milwaukee Time The Relative Times Lords Officers Logo Design Published 8 times a year by — Jay Badenhoop, Marti (2004-2005 term) The Milwaukee Time Lords Madsen, Linda Kelly c/o Lloyd Brown President th Contributors (Who to Blame): 2446 N. 69 Street Howard Weintrob . Wauwatosa, WI 53213-1314 Barbara Brown, John Brown, Andy DeGaetano, Debbie Frey, Dean Gustin, Jay Editor: ............. Barbara Brown Harber, Ed Hochman, and Marti Madsen. Vice President Art Editor ............ Marti Madsen Andy DeGaetano . News Editor .......... Mark Hansen And thanks to anyone whose name I may Newsletter Staff: have neglected to include. Treasurer Ellen Brown, Lloyd Brown Julie Fry.................... Secretary Ross Cannizzo............... Sergeant-at-Arms Contents Items in RED not included in web version Dean Gustin................. Meeting Schedule 3 Dalekmas Wishes 14 Chancellory 5 Fast Forward, pt. 3 17 Videos SF Databank 6 Blake’s 7 Spinoffs 24 Dean Gustin................. MTL 15th Anniversary 11 The Gallifrey Ragsheet 26 Fundraising From Beyond the Vortex Position open Newsletter Back to 28 pages again! I can breathe. Our cover is part of a much larger Barbara Brown............... drawing by Jay Harber. He did several versions of the same drawing – this one is of just the background. There are several versions with a rather nude Romana I, which are very good drawings, but which I can’t print in the Events newsletter. -

• New Audio Adventures Www

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES PAUL SPRAGG 1975 – 2014 ISSUE 64 • JUNE 2014 VORTEX PAGE 1 VORTEX PAGE 2 WELCOME TO BIG FINISH! WE LOVE STORIES AND WE MAKE GREAT FULL-CAST AUDIO DRAMA AND AUDIOBOOKS YOU CAN BUY ON CD AND/OR DOWNLOAD Our audio productions are based on much- You can access a video guide to the site by loved TV series like Doctor Who, Dark Shadows, clicking here. Blake’s 7, Stargate and Highlander as well as classic characters such as Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless and The SUBSCRIBERS GET MORE AT Adventures of Bernice Summerfield. BIGFINISH.COM! If you subscribe, depending on the range you We publish a growing number of books (non- subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs fiction, novels and short stories) from new and of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a established authors. bonus release and discounts. WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH /THEBIGFINISH VORTEX PAGE 3 VORTEX PAGE 4 EDITORIAL ’ve no idea when Big Finish became a big family. CHARITY FUNDRAISER Certainly it wasn’t a cynical, conscious decision on IN MEMORY OF PAUL I anyone’s part - and I’m sure if someone set out to make something similar, it would fail massively. I have a SPRAGG theory that the sense of family comes from a boss (Jason Haigh-Ellery) who is kind, considerate and a thoroughly decent human being, from an executive producer (Nick) who osing Paul Spragg on the 8th May this just trusts and leaves people to revel in being creative, from year has hit everyone who knew him L terribly. -

Technologies Journal of Research Into New Media

Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies http://con.sagepub.com Doctor Who and the Convergence of Media: A Case Study in `Transmedia Storytelling' Neil Perryman Convergence 2008; 14; 21 DOI: 10.1177/1354856507084417 The online version of this article can be found at: http://con.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/14/1/21 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies can be found at: Email Alerts: http://con.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://con.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://con.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/14/1/21 Downloaded from http://con.sagepub.com by Roberto Igarza on December 6, 2008 021-039 084417 Perryman (D) 11/1/08 09:58 Page 21 Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies Copyright © 2008 Sage Publications London, Los Angeles, New Delhi and Singapore Vol 14(1): 21–39 ARTICLE DOI: 10.1177/1354856507084417 http://cvg.sagepub.com Doctor Who and the Convergence of Media A Case Study in ‘Transmedia Storytelling’ Neil Perryman University of Sunderland, UK Abstract / The British science fiction series Doctor Who embraces convergence culture on an unprecedented scale, with the BBC currently using the series to trial a plethora of new technol- ogies, including: mini-episodes on mobile phones, podcast commentaries, interactive red-button adventures, video blogs, companion programming, and ‘fake’ metatextual websites. In 2006 the BBC launched two spin-off series, Torchwood (aimed at an exclusively adult audience) and The Sarah Jane Smith Adventures (for 11–15-year-olds), and what was once regarded as an embarrass- ment to the Corporation now spans the media landscape as a multi-format colossus. -

The Fourth Doctor

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES AWARD WINNING AUDIO DRAMA! THE FOURTH DOCTOR ADVENTURESLOUISE JAMESON ON WRITING AND STARRING IN THE THIRD SERIES PLUS! BLAKE’S 7: MICHAEL KEATING DOCTOR WHO: ANJLI MOHINDRA SPOOKY GOINGS-ON IN DARK SHADOWS! ISSUE 61 • MARCH 2014 VORTEX PAGE 1 VORTEX PAGE 2 WELCOME TO BIG FINISH! WE LOVE STORIES AND WE MAKE GREAT FULL-CAST AUDIO DRAMA AND AUDIOBOOKS YOU CAN BUY ON CD AND/OR DOWNLOAD Our audio productions are based on much- You can access a video guide to the site by loved TV series like Doctor Who, Dark Shadows, clicking here. Blake’s 7, Stargate and Highlander as well as classic characters such as Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless and The SUBSCRIBERS GET MORE AT Adventures of Bernice Summerfield. BIGFINISH.COM! If you subscribe, depending on the range you We publish a growing number of books (non- subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs fiction, novels and short stories) from new and of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a established authors. bonus release and discounts. WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH /THEBIGFINISH VORTEX PAGE 3 VORTEX PAGE 4 SNEAK PREVIEWS EDITORIAL AND WHISPERS CONTACT HAS BEEN MADE! ometimes, little things just strike you. I’ve always loved being a bit of an insider, ever since my previous job, as editor of Cult S Times magazine, gave me opportunities to meet the stars of he catchphrase from the 1977 Doctor my favourite series. And they were my favourite series; I went into Who story The Invisible Enemy is back, every interview totally familiar with my subject because I was T along with the fearsome Nucleus, in chatting to the stars of shows of which I’d watched every single Jonny Morris’s sequel Revenge of the Swarm episode. -

Dr Who Dvd Set

Dr who dvd set : Doctor Who - Complete Collection, DVD (Series Seasons , 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 Bundle) USA Format Region 1: Movies & TV. Your Doctor Who DVD Collection. There are currently Classic Doctor Who DVDs that have been announced/released with 37 box sets. You have a total of 0. Shop for doctor who dvd collection online at Target. Free shipping on purchases over $35 and save 5% every day with your Target REDcard. Find great deals on eBay for Doctor Who DVD Collection in Doctor Who DVDs and Videos. Shop with confidence. Find great deals on eBay for Doctor Who Box Set in DVDs and Movies for DVD and Blu-ray Disc Players. Shop with confidence. The Fall: Complete Collection. Quick View Doctor Who: Twice Upon a Time ( Christmas Special). Quick View . Big Pacific DVD. As David Tennant bids a fond farewell to his pinstripe suit and trainers, The Doctor Who Specials Boxset unites the final five thrilling episodes:Do. Having just received in the mail the last two Classic Series Doctor Who DVDs required to complete my collection, it's probably an appropriate. DOCTOR WHO: The Complete Series Seasons NEW DVD Set Includes: Season 1 through 9 Region: 1 (DVD): US, Canada. Added on. Most Doctor Who DVDs have been released first in the United Kingdom with Remembrance of the Daleks, Complete Series Two box set). A look at my Doctor Who DVD Collection. And yes folks since this was shot both The Web of Fear and the. The latest Doctor Who eps are now available on DVD and Bluray on two Series 10 sets. -

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who This article is about the television series. For other uses, see Doctor Who (disambiguation). Doctor Who Genre Science fiction drama Created by • Sydney Newman • C. E. Webber • Donald Wilson Written by Various Directed by Various Starring Various Doctors (as of 2014, Peter Capaldi) Various companions (as of 2014, Jenna Coleman) Theme music composer • Ron Grainer • Delia Derbyshire Opening theme Doctor Who theme music Composer(s) Various composers (as of 2005, Murray Gold) Country of origin United Kingdom No. of seasons 26 (1963–89) plus one TV film (1996) No. of series 7 (2005–present) No. of episodes 800 (97 missing) (List of episodes) Production Executive producer(s) Various (as of 2014, Steven Moffat and Brian Minchin) Camera setup Single/multiple-camera hybrid Running time Regular episodes: • 25 minutes (1963–84, 1986–89) • 45 minutes (1985, 2005–present) Specials: Various: 50–75 minutes Broadcast Original channel BBC One (1963–1989, 1996, 2005–present) BBC One HD (2010–present) BBC HD (2007–10) Picture format • 405-line Black-and-white (1963–67) • 625-line Black-and-white (1968–69) • 625-line PAL (1970–89) • 525-line NTSC (1996) • 576i 16:9 DTV (2005–08) • 1080i HDTV (2009–present) Doctor Who 2 Audio format Monaural (1963–87) Stereo (1988–89; 1996; 2005–08) 5.1 Surround Sound (2009–present) Original run Classic series: 23 November 1963 – 6 December 1989 Television film: 12 May 1996 Revived series: 26 March 2005 – present Chronology Related shows • K-9 and Company (1981) • Torchwood (2006–11) • The Sarah Jane Adventures (2007–11) • K-9 (2009–10) • Doctor Who Confidential (2005–11) • Totally Doctor Who (2006–07) External links [1] Doctor Who at the BBC Doctor Who is a British science-fiction television programme produced by the BBC. -

119 Starfleet Remembers Ben Kokochak and Ed

REGION 4 TOSSES A RINGER! 119 OCT/NOV 2003 REGION 4 HAS A CONFERENCE... ...and promptly started tossing their shoes. Horseshoes, that is. Top Row: Left: Charles Flowers of the USS Highroller demonstrates his pitching technique. Center: The clash of the titans! Charles Flowers and Charles Werner of the USS Peacekeeper get ready to rumble! Right: Charles Werner keeps his eyes on the prize. Center Left: Adam Bernay watches as Larry Barnes of the Shuttle Gallant gives it his best shot. Center Right: Region 5’s Jolynn Brown goes for the gold as Jennifer Cole of the USS Angeles watches on. Photos courtesy of: Pete Briggs and Glenda Werner REGION 7 HAS ONE, TOO! Meanwhile, back on the east coast of the United States, the fi ne art of Conferencing was practiced sans the pitching of equine footwear. Rain gear (thanks to hurricane Isabel) was much prefered. Left: RC R7 Alex Rosenzweig and Michael Klufas pose with STARFLEET Academies’ Blue Squadron Leader, Raven Avery. Right: Jon Slavin, Martin Lessem and Larry Neigut during the SFMC panel at the R7 Conference. Photos courtesy of: Mark H. Anbinder USPS 017-671 STARFLEET REMEMBERS BEN KOKOCHAK AND ED DeRUGGERIO FOR MORE, TURN TO PAGE 14. CONTENTS STARFLEET Communiqué Volume I, No. 119 Region 4 Tosses a Ringer!.....................1 From the Center Seat..............................3 Published by: Off-Center Viewpoint...............................4 STARFLEET: The International From the FDP Youth................................4 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. EC/AB News............................................4 3212 Mark Circle Remembering Those Who Came Before..4 Independence, MO 64055 Ops Center..............................................5 SFI Morale Offi ce Help Neeeded...............5 Chrissy Killian and Larry Barnes congratulate one another for Publisher: Greg Trotter COMM As You Are..................................6 Editor in Chief: Dixie Halber The Return of SFI Memory Alpha.............6 surviving one more Region 4 Conference. -

Docton Whoco$Tuwvl~

50 yetl rs of DOCTon WHO Co$tuWvL~ By Jean Martin and Christopher Erickson "Doctor Who" is a classic, long-running British science also been sighted at Renaissance Faires in California and fiction show that began in 1963 about a time-traveling alien The Great Dickens Christmas Fair in San Francisco. There who regenerates, has adventures, saves the universe and has have also been events inspired by "Doctor Who" such as the affection for the human race. "Doctor Who" has become recent PEERS The Doctor Dances Ball, which was set even more popular since its re-launch in 2005, and you can during the London Blitz. Lastly, fans can just get together see fans in costumes from its 50-year run at numerous and party to watch the episodes in costumes. For the 50th conventions and events. anniversary simulcast screening in movie theatres last Examples of places you can go to wear these costumes November 23, some attendees came in costume. are "Doctor Who" conventions such as Gallifrey One in With 50 years of episodes to choose from, fans have a Los Angeles, Chicago TARDIS, Hurricane Who in Florida wealth of costume inspirations from the 11 Doctors (so far) and L.I. Who in New York. Regular science fiction, fantasy, who mostly wear suits that are either based on various time comic book and pop culture conventions are also good periods or are whimsical creations. As for the Doctors' places to go for "Doctor Who" costuming especially when companions, who are mostly female, their costumes some of the actors in the show are guests. -

Cons & Confusion

Cons & Confusion The almost accurate convention listing of the B.T.C.! We try to list every WHO event, and any SF event near Buffalo. updated: Oct. 28, 2020 to add an SF/DW/Trek/Anime/etc. event; send information to: [email protected] PLEASE DOUBLECHECK ALL EVENTS, THINGS ARE STILL BE POSTPONED OR CANCELLED. SOMETIMES FACEBOOK WILL SAY CANCELLED YET WEBSITE STILL SHOWS REGULAR EVENT! JUNE 12-14 PA SCI-FI VALLEY CON 2020 POSTPONED TO JUNE 18-20, 2021 SF/Fantasy media https://www.scifivalleycon.com/ JUNE 12-14 Pitt THE LIVING DEAD WEEKEND POSTPONED TO NOV 6-8, 2020 Horror! http://www.thelivingdeadweekend.com/monroeville/ JUNE 12-14 NJ ANIME NEXT 2020 CANCELLED anime/manga/cosplay http://www.animenext.org/ JUNE 13-14 RI THE TERROR CON POSTPONED, no date set horror con https://www.theterrorcon.com/ JUNE 19-21 Phil WIZARD WORLD CANCELLED will return in 2021 media/comics/cosplay https://wizardworld.com/comiccon/philadelphia JUNE 19-21 T.O. INT'L FAN FESTIVAL TORONTO POSTPONED, no new date yet anime/gaming/comics https://toronto.ifanfes.com/ JUNE 19-21 Pitt MONSTER BASH CONFERENCE CANCELLED, see October event horror film/tv fans https://www.monsterbashnews.com/bash-June.html JUNE 20-21 Cinn SCI-CON 2020 CANCELLED will return in 2021 media/science/cosplay http://www.ctspromotions.com/currentshow/ JUNE 20-21 IN RAPTOR CON POSTPONED to Dec 12-13, 2020 anime/geek/media https://lind172.wixsite.com/rustyraptor/ JUNE 27-28 Buf LIL CON 7 POSTPONED, no new date announced yet http://lilconconvention.com/ JUNE 28 Buf PUNK ROCK FLEA MARKET & GEEK GARAGE -

Diary of the Doctor Who Role-Playing Games, Issue

VILLAINS ISSUE The fanzine devoted to Doctor Who Gaming ISSUE # 14 CONTINUITY„THIS IN GAMINGMACHINE - KILLSCH FASCISTS‰ ADVENTURE MODULE NEW FASA„MORE VILLAIN THAN STATS MONEY‰ - CREATING ADVENTURE GOOD VILLAINS MODULE and MORE...ICAGO TARDIS 2011 CON REPORT 1 EDITOR’S NOTES CONTENTS Hi there, Some of our issues feature a special theme, so we EDITOR’S NOTES 2 welcome you to our “Villains Issue”. This is a fanzine that REVIEW: The Brilliant Book 2012 3 concentrates on helping GMs create memorable and ef‐ Angus Abranson Leaving Cubicle 7 4 fective villains in their game. Villain motivations, villain Face to Face With Evil 5 tools and more can be found in these pages. Neil Riebe Not One, But Two, Episodes Recovered 11 even gives us retro FASA stats for Androgums, who can Why Are Your Doing This?! 12 be used as villains or standard characters. Hopefully Gamer Etiquette 105 14 there will be something fun for you to use in your next The Villain’s Toolkit 15 adventure. Continuity in Gaming 16 A review of the Chicago TARDIS 2012 convention New FASA Villain Stats: Androgums 18 is included in this issue, where our staff did a session on REVIEW: Everything I Need to Know I Learned From Doctor Who RPGs and also ran an adventure using the Dungeons & Dragons 23 Cubicle 7 DWAiTS rules as well. Staff member Eric Fettig MODULE: “This Machine Kills Fascists” 24 made it his first official Doctor Who convention (having EVENT REPORT: Chicago TARDIS 2011 Con 28 attended many gaming conventions before that) and Viewpoint of a First Time Who Con Attendee 43 gives us a look from his first timer’s perspective.