UK Support to Post- Earthquake Recovery in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2017-18-RIMS Nepal

2018-19 ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 1 Annual Report 2017-18 Citation: RIMS Nepal (2018), Annual Report 2017-2018, Kathmandu, Nepal: RIMS Nepal. Copyright © 2018 All rights reserved. RIMS-Nepal would appreciate receiving a copy of any material that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing to the publisher. Publisher Resource Identification and Management Society-Nepal (RIMS-Nepal) P.O. Box: 2464 (Kathmandu) Email: [email protected] Tel: +977-1-5224091, 5224094 (Kathmandu Office) Website: www.rimsnepal.org.np Editorial Team Bishnu Tripathi, Rabindra Shrestha, and Harihar Kafle Contributors Mahesh Chhetri (PAHAL), Khem Oli (ANUKULAN), Chetnath Tripathi (FOSTER/AREA), Dabal Bam (HOME GARDEN), Ram Raja Shahi (SWASTHA/EWASH), Laxmi Prasad Sharma (PRRO II and III) Front Cover Photos RIMS-Nepal Photo Archive Design & Print Production RIMS-Nepal Photo Archive Annual Report 2017-18 2 CONTENTS Message from The Chairperson and The Executive Director ........................................................ 5 Abbreviations & Acronyms ................................................................................................................... 6 RIMS Nepal at a glance ......................................................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... -

Gorkha, Dhading, Nuwakot And

VOLUME A: Detailed Study of Poverty and Vulnerability in Four Earthquake-Affected Districts in Nepal: Gorkha, Dhading, Nuwakot and Rasuwa Nepal Development Research Institute September, 2017 Project Team Members Team Leader Prof. Dr. Punya P. Regmi Poverty and Vulnerability Expert (Deputy Team Leader) Dr. Nirmal Kumar B.K. Livelihood & Disaster Risk Reduction Expert Mr. Dhanej Thapa Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Expert Dr. Manjeshwori Singh Anthropology Expert Dr. Rabita Mulmi Shrestha Migration Expert Mr. Kabin Maharjan GIS Expert Ms Anita Khadka Design and Layout Copyright © 2017 All rights reserved Nepal Development Research Institute (NDRI) Web: http://www.ndri.org.np Acknowledgements This report “A Detailed Study of Poverty and Vulnerability in Four Earthquake-Affected Districts: Dhading, Gorkha, Nuwakot and Rasuwa” was prepared by Nepal Development Research Institute (NDRI) in collaboration with the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS), Nepal Operations Center and Department for International Development (DFID), Nepal. On behalf of NDRI, I would like to express my gratitude to UNOPS for awarding us this important assignment. Similarly, I highly appreciate the support received from the entire DFID team, especially from Mr. Curtis Palmer, Team Leader Field Office and Ms Amita Thapa Magar, Field Officer, DFID for their persistent guidance in the study and critical comments and suggestions in the report. I extend my hearty gratitude to the field researchers for their dedicated efforts and for working in such challenging situations. The effective coordination facilitated by local agencies and DFID field officers during field work in the study districts was also praiseworthy, without which the field work would not have been possible. -

Rural Municipality Transport Master Plan(RMTMP)

Local Government Gangajamuna Rural Municipality Office of the Rural Municipal Executive Phulkharka, Dhading Bagamati Province, Nepal Rural Municipality Transport Master Plan (RMTMP) Volume- I-Main Report Final Draft Submitted By Sarthak Engineering Consultancy Pvt. Ltd. Baneshwor, Kathmandu Gangajamuna Rural Municipality Office of the Rural Municipal Executive Bagmati Province, Dhading district This document is the draft report prepared for the project, “Rual Municipality Transport Master Plan (RMTMP)” undertaken by Gangajamuna Rural Municipal Office, Dhading district. This document has been prepared by Sarthak Engineering Consultancy Pvt. Ltd. for Gangajamuna Rural Municipality, Office of the Rural Municipal Executive, Dhading district. The opinions, findings and conclusions expressed herein are those of the Consultant and do not necessarily reflect those of the Rural Municipality. Data Sources and Credits Data sets, drawings and other miscellaneous data are produced/ developed by Sarthak Engineering Consultancy Pvt. Ltd. for the project during 2019/2020. These data are owned by Gangajamuna Rural Municipality, Office of the Rural Municipal Executive, Dhading. Authorization from the owner is required for the usage and/or publication of the data in part or whole. Name of the Project Rural Municipality Transport Master Plan (RMTMP) of Gangajamuna Rural Municipality Project Executing Agency Gangajamuna Rural Municipality Office of the Rural Municipal Executive Bagmati Province, Dhading district Implementing Agency Gangajamuna Rural Municipality -

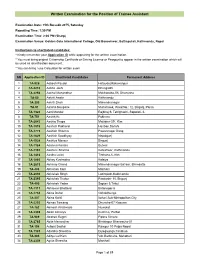

Written Examination for the Position of Trainee Assistant

Written Examination for the Position of Trainee Assistant Examination Date: 15th Baisakh 2075, Saturday Reporting Time: 1:30 PM Examination Time: 2:00 PM (Sharp) Examination Venue: Golden Gate International College, Old Baneshwor, Battisputali, Kathmandu, Nepal Instructions to shortlisted candidates: * Kindly remember your Application ID while appearing for the written examination. * You must bring original Citizenship Certificate or Driving License or Passport to appear in the written examination which will be used as identification document. * You can bring / use Calculator for written exam. SN Application ID Shortlisted Candidates Permanent Address 1 TA-926 Aabesh Paudel Hetauda,Makawanpur 2 TA-2210 Aabha Joshi Dhangadhi 3 TA-2254 Aachal Manandhar Makhanaha-08, Dhanusha 4 TA-60 Aakriti Awale Kathmandu 5 TA-303 Aakriti Shah Mahendranagar 6 TA-51 Aalisha Neupane Murlichowk, Ward No.: 12, Birgunj, Parsa 7 TA-1320 Aarti Mandal Rajbiraj-9, Tetrighachi, Sapatari- 6. 8 TA-751 Aashik Kc Pokhara 9 TA-2643 Aashiq Thapa Maitidevi-29 , Ktm 10 TA-1919 Aashish Pokharel Hariban,Sarlahi 11 TA-1775 Aashish Sharma Pawannagar Dang 12 TA-1629 Aashish Upadhyay Nepalgunj 13 TA-1924 Aashiya Mansur Birgunj 14 TA-1184 Aashma Koirala Butwal 15 TA-1191 Aashree Sharma Koteshwor, Kathmandu 16 TA-1416 Aastha Luitel Tinthana-6, Ktm 17 TA-1880 Abhay Kushwaha Kalaiya 18 TA-2619 Abhinay Chand Mahendranagar Bazaar, Bhimdatta 19 TA-408 Abhishek Karn Matihani 20 TA-2030 Abhishek Singh Lazimpath,Kathmandu 21 TA-2395 Abhishek Thakur Panitanki- 10, Birgunj 22 TA-490 Abhishek -

English Grammar & Composition

DYNAMIC ENGLISH GRAMMAR & COMPOSITION 10 Author Krishna Prasad Regmi Edited by Koushalya Gurung Publisher Shubharambha Publication Pvt. Ltd. Kathmandu, Nepal This book belongs to: Name: .............................................................................. Class: ............................................................................... Roll Number: ............................................................................... Address: .............................................................................. Contact Number: ............................................................................... Author : Krishna Prasad Regmi Layout Design : Ram Malakar Copyright © : Publisher New Edition : 2075 Revised Edition: 2077 Publication : Shubharambha Publication Pvt. Ltd. Kathmandu, Nepal Preface Dynamic English Grammar and Composition has been designed according to the new English Curriculum prescribed by the Curriculum Development Centre. The series comprises of ten textbooks from grade one to grade ten. The present book is an amalgamation of survey of rules, structures and forms presented in lucid modern English and illustrated with numerous examples. The aim of this book is to bring about a change in teaching and learning English grammar and composition-a change that will enable the learners to use grammar in context using both inductive and deductive approaches aiming to develop four language skills immensely. Practice in composition tasks will help to develop the learner’s writing skills. It will encourage to writing -

VOLUME A: Detailed Study of Poverty and Vulnerability in Four

VOLUME A: Detailed Study of Poverty and Vulnerability in Four Earthquake-Affected Districts in Nepal: Gorkha, Dhading, Nuwakot and Rasuwa Nepal Development Research Institute September, 2017 0 Project Team Members Team Leader Prof. Dr. Punya P. Regmi Poverty and Vulnerability Expert (Deputy Team Leader) Dr. Nirmal Kumar B.K. Livelihood & Disaster Risk Reducation Expert Dhanej Thapa Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Expert Dr. Manjeshwori Singh Anthropology Expert Dr. Rabita Mulmi Shrestha Migration Expert Kabin Maharjan GIS Expert Anita Khadka Edited by: Design and Layout Cover Photo: Copyright © 2017 All rights reserved Nepal Development Research Institute (NDRI) Web: http://www.ndri.org.np i Acknowledgements This report “A Detailed Study of Poverty and Vulnerability in Four Earthquake-Affected Districts: Dhading, Gorkha, Nuwakot and Rasuwa” was prepared by the Nepal Development Research Institute (NDRI) in collaboration with the United Nations Office for Project Offices (UNOPS), Nepal Operations Center and Department for International Development (DFID), Nepal. On behalf of NDRI, I would like to express my gratitude to UNOPS for awarding us this important assignment. Similarly, I highly appreciate the support received from the entire DFID team, especially from Mr. Curtis Palmer, Team Leader Field Office and Ms Amita Thapa Magar, Field Officer, DFID for their persistent guidance in the study and critical comments and suggestions in the report. I extend my hearty gratitude to the field researchers for their dedicated efforts and for working in such challenging situations. The effective coordination facilitated by local agencies and DFID field officers during field work in the study districts was also praiseworthy, without which the field work would not have been possible.