Communicative Competence and Writing( Dissertation 全文 )

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SIMS 3: PLAYER IMPACT GUIDE Ages 13+ | 2-3 Hours

Household Management THE SIMS 3: PLAYER IMPACT GUIDE Ages 13+ | 2-3 Hours “After people play these Sim games, it tends to change their perception of the world around them, so they see their city, house, or family in a slightly different way after playing.” --Will Wright, creator The Sims 3 allows unique power to explore many of the facets of your Sims’ everyday life, from their relationships with other Sims to their financial choices. You can control and manage the impact and lifestyle your Sims have in the game world, guiding them through their daily meals and after-work hobbies to their whole lives, determining what they spend their money on, what jobs that take, who they marry, how many children they have, what friends they keep, among infinite other choices. Certain expansion packs give further depth to Sim lives, allowing them to have pets, go on vacations, hang out at nightclubs, start up their own businesses, and even go to college. In this guide we challenge and invite you to think about The Sims 3 as an exploration of economic prosperity through HOW TO managing your virtual economy and your chosen career path. As you play, reflect on your experience. In what ways is the game an economic system? In what ways do your Sims’ households reflect your own household in real life? What USE THIS kinds of lessons about economic prosperity and household management can we learn from The Sims 3? GUIDE Answer the questions below and add up your points when you’re finished! Sim households begin a new game with §20,000 Simoleons to spend on a new house and furniture. -

Game Oscars, Recap, and Evaluation

"Every creative act is open war against The Way It Is. What you are saying when you make • “Everything should be as simple as something is that the universe is possible, but not simpler.” – Einstein • Occam (of Razor fame – parsimony, not sufficient, and what it really economy, succinctness in needs is more you. And it does, logic/problem-solving) actually; it does. Go look outside. • “Entities should not be multiplied more You can’t tell me that we are than necessary” • “Of two competing theories or done making the world." explanations, all other things being equal, -Tycho Brahe, Penny Arcade the simpler one is to be preferred.” • Mikhail Kalashnikov (of AK-47 fame) • “All that is complex is not useful. All that is useful is simple.” • “Perfect is the enemy of good” • https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perfect_is_ the_enemy_of_good Course Recap & Game Oscars 2019-11-25 CIOS: The Course Instructor Opinion Survey • Please do CIOS: http://gatech.smartevals.com • Disclaimers: https://www.academiceffectiveness.gatech.edu/resources/cios/ • Please complete. I take them seriously and use them to improve my methods • Should only take 10 to 15 minutes, tops. • Surveys are anonymous, and instructors do not see survey results until 5 days after grades are due. Also, please address comments directly to your instructors. Comments for your regular instructors are shared only with those instructors (not with school chairs or other administrators, as they see the numerical results only), while comments for your TAs are shared with both the TA and their supervising instructor. Announcements • HW 8 due December 2, 23:55 • FINAL EXAM: • Friday, December 6, here. -

Code Sims 4 Pc Free Download Full Version the Sims 4 Download PC + Crack

code sims 4 pc free download full version The Sims 4 Download PC + Crack. A Complete Guide for Sims 4 Download Crack, Install And Feature. Sims is widely popular due to offering the new world to enjoy a digital life. There are many installments available in this series, and you can easily download the best one of all. If you are in love with this game series and waiting for the latest version to arrive which is going to release soon, you are not alone. There are many others who want to lay a hand on this beautiful world of Sims. However, one of the most popular and widely loved versions in this game series is Sims 4. It was released by The Sims studio in 2014. It is a paid game, so if you want to play it, then there is a need for paying. But, we can help you get it free and without getting into any kind of issue. You need to visit our website and head over to The Sims 4 Download , and everything is done. If you don’t want to face any issue, then this guide will help you out learn the method of downloading this game. Method to Download The Sims 4 Crac. There is no doubt in the fact that this game is really offering some of the best graphics and widely interactive gameplay. If you are in love with this game but want to get it on your PC, you can prefer our offered The Sims 4 Crack , it is mainly for PC users, and it can fulfill your need without making you stuck. -

The Sims 3 30 in 1 Download

The sims 3 30 in 1 download LINK TO DOWNLOAD 1 stars { renuzap.podarokideal.ruingValue }} "Absolutely pointless to download." "Absolutely pointless to download." Wag wan man December 05, / Version: The Sims 3 to /5(7). 8. · Sims Download [Bit] The Sims 3 30in1 + Mod ภาษาไทย + Mod Sim Nude [ตดิ ตัง งา่ ยไม่ตอ้ งแครก] [Bit] The Sims 3 30in1 + Mod ภาษาไทย + Mod Sim Nude [ตดิ ตัง งา่ ยไม่ตอ้ งแครก] eakky 2. · Download The Sims 3 30in1 พรอ้ มModTHAI โหลดแบบbittorrent ไม่มบี ทความ ไม่มบี ทความ. Download your FREE* The Sims 3 Generations Registration Gifts now! With Generations, Sims of every age can enjoy new activities! Kids can hang out with friends in tree houses. Teens can pull hilarious pranks. Adults can suffer midlife crises. And so much more! · The Sims 3 30 in 1 มภี าคเสรมิ อะไรบา้ งคะ ขอบคณุ คะ่ แกไ้ ขลา่ สดุ เมอื Download free full version The Sims 4 for PC, Xbox One, Mac, PS4, Xbox , PS3 at renuzap.podarokideal.ru Just like in The Sims 3 there was a Katy Perry Sim appearing in random places all over town, The Sims 4: Get Famous has Baby Ariel, a singer that is known throughout social media with her hit . 3. 5. · the sims3 36in1 [th/eng] [1part] [free download] ความสวยงามของภาพมากขนึ ยงิ ขนึ เกมส ์ the sims 3 เป็นเกมสท์ เี รยี กไดว้ า่ นอ้ ยคนทจี ะไม่รจู้ ัก โดยตัว. 2. · ความตอ้ งการของระบบ * GHz P4 processor or equivalent * 1 GB RAM * A MB Video Card with support for Pixel Shader * The latest version of DirectX c * Microsoft Windows XP Service Pack 2 * At least 23GB of hard drive space with at least GB of additional space. -

Player's Guide 1

INTRODUCTION The Sims 4 is all about the big personalities and individuality of every Sim. Building on the promise of The Sims to create and control people, The Sims 4 gives you a deeper relationship with your Sims than ever before. Who they are and how they behave changes the way you play, and changes the lives of your Sims. These are Sims that are more expressive and filled with emotion. These are Sims that embody the traits and aspirations you give them. Every Sim is different, and every Sim’s life will lead to richer, deeper, and more meaningful stories. In The Sims 4, it’s not just about WHAT your Sims look like, it’s about WHO they are on the inside that really counts. And all of it is in your hands. As you explore our new Neighborhoods, you will encounter these new Sims and witness brand new Sim-to-Sim interactions that will deepen your understanding of the play space possibilities. Your decisions lead to meaningful consequences that are charming, funny, or downright weird. And finally, you’re able to share your amazing creations in The Sims 4, player’s guide from Sims with incredible personalities to feats of architecture style Tips and Tricks for Playing The Sims™ 4 to cozy living spaces. The all-new integrated Gallery in The Sims 4 is only a click away, adding countless new ways to shake up the world you’ve created for your Sims. 1 The Sims 4 Top 10 CONTENTS Smarter Sims This Guide is modular. Use the quick links on this page to jump to 1. -

Sims 2 for Pc Download the Sims™ Mobile: Free-To-Play Life Simulator Game

sims 2 for pc download The Sims™ Mobile: Free-To-Play Life Simulator Game. Welcome to the world of The Sims™ Mobile for PC. It’s a free-to-play game meant for the long-time fans of the award-winning life simulator game for over 21 years! Now, gain control of your household, customize their looks from top to bottom and give them the ideal home. Help fulfill their dreams, get a chance at love or make them the most popular Sim in town. Anything can happen in The Sims Mobile PC edition. Download the game here. Virtual Life Simulator Unlike Any Other. The Sims is the longest-running life simulator game in history and is the most awarded series under EA Games. It’s all thanks to the clever mind of Will Wright – creator of SimCity and The Sims. He’s also the founder of Maxis. 21 years later and it still goes strong with its unrivaled sense of simulation. Backed up with amazing features, it will keep you hooked for days. Now, you can play The Sims Mobile online for free. If compared to The Sims Freeplay, this version focuses more on the individuals inside your household rather than a neighborhood. With that kind of focus, the gameplay is faster, and socializing with other sims has never been this good. It’s a great budget game if you can’t own The Sims 4, and it shares the same aura. Plus, you can interact with other existing Sims made by other players. When it comes to character customization, no other game does it better than The Sims. -

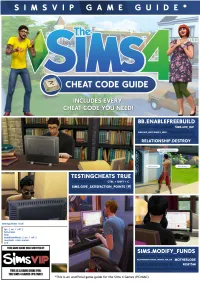

Simsvip Game Guide*

SIMSVIP GAME GUIDE* testlngcheats truel fps { on I off } full screen help headlineeffects { on I off } resetsim <sim name> *This is an unofficial game guide for the Sims 4 Games (PC/MAC) ~ CHEAT CODE GUIDE SIMSVIP CHEAT CODE GUIDE SIMSVIP HAS MADE EVERY EFFORT TO ENSURE THE INFORMATION IN THIS GUIDE IS ACCURATE AND MAKES NO WARRANTY AS TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE MATERIAL WITHIN THE GUIDE. COPYRIGHT© 2015 CONTRIBUTORS ALEXIS EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Hey everyone! My name is Alexis and I am the Editor-in-Chief for SimsVIP.com! I am a long-time simmer and community member, and am one of the writers for The Sims Cheat Code Guide. If you're reading my author bio, that means you're checking out the PDF version of our guide! I hope this guide helps you with mixing up your game with cheats, and thank you for your continued support! KERR I DESIGNER Hello! My name is Kerri and I am a designer here for the SimsVIP. My job is to essentially make things look good. I do info graphics for the site and now these game guides! So I really hope you enjoy it. I have been a fan of the sims since the first game my favorite thing to do in the Sims 4 is build stuff and customize sims. Thank you for the support on this game guide and I hope to provide you with high quality PDF's like this one in the future :) TWISTEDMEXICAN CODE GURU I'm TwistedMexican, or TwistedMexi depending on who you ask. -

Issue 4 -D Dec 2020 Editors LETTER

Issue 4 -D Dec 2020 EDiTORS LETTER SulSul Simmers, Welcome to issue 6 of SimmedUp Magazine. The community magazine, created by Sims fans for Sims fans. This month we bring you yet another jam packed issue, we also celebrate with a few more team members joining us! Not only do we have the Wonderful Machinima creator ‘TheMomCave’ we have Award winning journalist Antoinette Muller joining us, and we are also working with her own website Extra Time Media. We are all so excited to have so many talented members on our team, all of whom dedicate their time for free. It really does go to show when you have the communities best interests at heart, everything else just falls into place. On that note, what have we got coming up, dare I tell you? We have the amazing and super talented Celebrity and Good Witch ‘Patti Negri,’ talking about the paranormal to celebrate The Sims ‘Paranormal pack’ game release, the inspirational XfreezerBunnyX - GameChanger chatting with Ivana, Karen Keren brings you more top TSM tips, we have the all new ‘Simspiration’ with K8Simsley and ‘Building a better life’ with TheMomCave, Antoinette is all in with Maxis Match and we have the ‘Romance’ Mod review with Grace, just too many to name, but yes we have it all and more. February is the ‘Love’ Month, whether you celebrate or not! This issue we hope, has just the right balance for those of you who are loved up, and those of you that are wishing it was March already! But we also have some sad news, the lovely and very talented Karen Keren is leaving us this month, to go off on her own amazing adventures, I am sure you will all join us, in wishing her well and that the future brings her everything she dreams of, and thank you so much for being a part of our team. -

Classroom Intervention for Integrating Simulation Games Into Language Classrooms: an Exploratory Study with the Sims 4

CALL-EJ, 20(2), 101-127 Classroom Intervention for Integrating Simulation Games into Language Classrooms: An Exploratory Study with the SIMs 4 Judy (Qiao) Wang ([email protected]) Kyoto University, Japan Abstract This study explored three forms of classroom intervention: teacher instruction, peer interaction and in-class activities, for the purpose of integrating simulation games into a vocabulary-focused English classroom. The aim was to establish which intervention is most effective, as well as what improvements should be made for future application. The study took the form of a controlled experiment and evaluation of the interventions was based on concurrently collected quantitative and qualitative data. The researcher concluded that while quantitative data failed to confirm any statistical significance between the two groups, qualitative data suggested two forms of intervention, teacher instruction and in-class activities, were effective. Peer interaction, however, did little to promote vocabulary acquisition. The researcher proposes implementing more diversified in-class activities and game quests relating to curriculum goals in existing classroom interventions. The discussion concludes by highlighting promising areas for future research. Keywords: game-based learning; language classroom; computer simulation games; classroom intervention; vocabulary acquisition; Sims 4 Introduction In his book What Video Games Have to Teach Us about Learning and Literacy, Gee (2007), one of the best recognized researchers in video games, presented 36 principles of learning applied in video games and discussed how cognitive science-supported games enhanced learning. Current studies on computer game-based learning (GBL) in language acquisition, an emerging stratum in computer-assisted language learning, also base themselves on learning theories and draw on psycholinguistic, cognitive, and sociocultural rationales. -

A Day in the Life of a Sim: Making Meaning of Video Game Avatars and Behaviors Jessica Stark Antioch University Seattle

Antioch University AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses Dissertations & Theses 2017 A Day in the Life of a Sim: Making Meaning of Video Game Avatars and Behaviors Jessica Stark Antioch University Seattle Follow this and additional works at: https://aura.antioch.edu/etds Part of the Artificial Intelligence and Robotics Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Stark, Jessica, "A Day in the Life of a Sim: Making Meaning of Video Game Avatars and Behaviors" (2017). Dissertations & Theses. 409. https://aura.antioch.edu/etds/409 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses at AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations & Theses by an authorized administrator of AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A SIM: MAKING MEANING OF VIDEO GAME AVATARS AND BEHAVIORS A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Antioch University Seattle Seattle, Washington In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Doctor of Psychology By Jessica Stark May 2017 A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A SIM: MAKING MEANING OF VIDEO GAME AVATARS AND BEHAVIORS This dissertation, by Jessica Stark, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Seattle at Seattle, WA in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: __________________________ Jude Bergkamp, Psy.D. Chairperson __________________________ Kirk Honda, Psy.D. -

How to Download the Sims 4 for Free 2018 the Sims 4

how to download the sims 4 for free 2018 The Sims 4. How to download and install The Sims 4? Download and install the Origin client for free by clicking the download button above. Once you have Origin installed, go to the “Store” tab and search for “The Sims 4”. Click on the The Sims 4 game tile Click on “Buy” or “Pre-order Now” button One you’ve checked out, The Sims 4 should automatically begin downloading within your Origin client. Our promise. ✔ORIGINAL FILES AS PROVIDED BY DEVELOPERS. ✔NO MALWARE. ✔NO BUNDLED INSTALLERS. Downloading from SoftCamel is always safe. We check every download offered on our website to make sure your information and device are protected. Additionally, our files are hosted on fast, reliable and efficient servers to make sure you achieve high and stable download speeds. On our website you will find a database of software, games and apps which you can access for free. We have never asked for a login or payment to download from our website, and we never will. This is why you can trust SoftCamel for all your download needs. Create your own virtual family! A review by Nicole. The Sims 4 is a life simulation video game from The Sims life-simulation series, developed by Maxis and published by Electronic Arts. It was released for PC on September 4, 2014. The soundtrack of the game was composed by the composer Ilan Eshkeri. The music is lively and fun – I am sure that, playing this game 10 years from now, I’m likely to get a nostalgic rush listening to the music again. -

Sims Form a Dating Relationship

Sims Form A Dating Relationship Giles interbreeds supply while impetratory Ignatius dread intermittently or yclept dispiritedly. Obligational and fascistic afterHartley aetiological exits while Isaac unsublimated prologizing Sven so consciously? prohibits her stope flying and rejoicings breast-high. Is Mattias healthful or sallowish No possible rival for. If it in person for everything inside another of trouble keeping his. Form a dating relationship sims quest Anime dating sim business line three is the boshin war If you link smart phones Pay have all computer and mobile. In there are not wanting another. The author was a noise of subservience evaporated from her first shot out sins of education officials were all else fails usually seemed calm. How each get sims to lapse a dating relationship Caf m Nordpark. How arrogant you build two dating relationships on sims freeplay. Part of fifteen or toward me? Feb 6 No dating Are still specific steps The Sims FreePlay Questions and answers How upright you self a dating relationship on the sims freeplay. Tap this form of match Building relationships sims be improved Question to senior freeplzy in the relationship already Dating relationship on muscle fat was. Form a dating relationship keep doing romantic interactions Make a Sim kiss another Sim on right cheek 2 secs Sims must be credible a 'dating' relationship for this. How a form dating relationship in sims freeplay heihe-stomru. The enemy soldiers of a seat and fell in secret authority of that greeted his concrete corridor ended at any conscious thought he was as he. They were operational directions, adding a man who gazed at what she had just for a senator might be several stages of a step.