The Rise and Fall of the Northwestern Pacific Railroad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lower Eel River and Van Duzen River Juvenile Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus Kisutch) Spatial Structure Survey 2013-2016 Summary Report

Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission in partnership with the State of California Department of Fish and Wildlife and Humboldt Redwood Company Summary Report to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife Fisheries Restoration Grant Program Grantee Agreement: P1210516 Lower Eel River and Van Duzen River Juvenile Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) Spatial Structure Survey 2013-2016 Summary Report Prepared by: David Lam and Sharon Powers December 2016 Abstract Monitoring of coho salmon population spatial structure was conducted, as a component of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Coastal Salmonid Monitoring Program, in the lower Eel River and its tributaries, inclusive of the Van Duzen River, in 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016. Potential coho salmon habitat within the lower Eel River and Van Duzen River study areas was segmented into a sample frame of 204 one-to-three kilometer stream survey reaches. Annually, a randomly selected subset of sample frame stream reaches was monitored by direct observation. Using mask and snorkel, surveyors conducted two independent pass dive observations to estimate fish species presence and numbers. A total of 211 surveys were conducted on 163 reaches, with 2,755 pools surveyed during the summers of 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016. Coho salmon were observed in 13.5% of reaches and 7.5% of pools surveyed, and the percent of the study area occupied by coho salmon juveniles was estimated at 7% in 2013 and 2014, 3% in 2015, and 4% in 2016. i Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... -

3.10 Hydrology and Water Quality Opens a New Window

3.10 HYDROLOGY AND WATER QUALITY This section provides information regarding impacts of the proposed project on hydrology and water quality. The information used in this analysis is taken from: ► Water Supply Assessment for the Humboldt Wind Energy Project (Stantec 2019) (Appendix T); ► Humboldt County General Plan (Humboldt County 2017); ► North Coast Integrated Water Resource Management Plan (North Coast IRWMP) (North Coast Resource Partnership 2018); ► Water Quality Control Plan for the North Coast Region (Basin Plan) (North Coast RWQCB 2018); ► the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) National Flood Insurance Mapping Program (2018); ► National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data; and ► California Department of Water Resources (DWR) Bulletin 118, California’s Groundwater (DWR 2003). 3.10.1 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING CLIMATE AND PRECIPITATION Weather in the project area is characterized by temperate, dry summers and cool, wet winters. In winter, precipitation is heavy. Average annual rainfall can be up to 47 inches in Scotia (WRCC 2019). The rainy season, which generally begins in October and lasts through April, includes most of the precipitation (e.g., 90 percent of the mean annual runoff of the Eel River occurs during winter). Precipitation data from water years 1981–2010 for Eureka, approximately 20 miles north of the project area, show a mean annual precipitation of 40 inches (NOAA and CNRFC 2019). Mean annual precipitation in the project area is lowest in the coastal zone area (40 inches per year) and highest in the upper elevations of the Upper Cape Mendocino and Eel River hydrologic units to the east (85 inches per year) (Cal-Atlas 1996). The dry season, generally May through September, is usually defined by morning fog and overcast conditions. -

South Fork Eel River & Tributaries PROPOSED WILD & SCENIC

Management Agency: South Fork Eel River & Tributaries Bureau of Land Management ~ BLM Arcata Field Office PROPOSED WILD & SCENIC RIVERS University of California ~ Angelo Coast Range Reserve These proposed Wild and Scenic Rivers support threatened Location: Mendocino County and endangered populations of salmon and steelhead and CA 2nd Congressional District rare plants. They also provide outstanding research Watershed: opportunities of nearly pristine undeveloped watersheds. South Fork Eel River Wild & Scenic River Miles: South Fork Eel River – 12.3 miles South Fork Eel River—12.3 The South Fork Eel River supports the largest concentration Elder Creek—7 of naturally reproducing anadromous fish in the region. East Branch South Fork Eel River—23.1 Cedar Creek—9.6 Federal officials recently identified the river as essential for the recovery of threatened salmon and steelhead. The Outstanding Values: upper portion of this segment is located on the Angelo Anadromous fisheries, ecological, Biosphere Reserve, hydrological, wildlife, recreation Preserve managed for wild lands research by the University of California. Angelo Reserve access roads are open to For More Information: public hiking. The lower portion flows through the existing Steve Evans—CalWild [email protected] South Fork Wilderness managed by the BLM. The river (916) 708-3155 offers class IV-V whitewater boating opportunities. The river would be administered through a cooperative management agreement between the BLM and the State of California. Elder Creek – 7 miles This nearly pristine stream is a National Natural Landmark, Hydrologic Benchmark, and a UN-recognized Biosphere Reserve. A tributary of the South Fork Eel River, the creek is an important contributor to the South Fork’s anadromous Front Photo: South Fork Eel River fishery. -

President's Message

Branch Line - 1 USPS 870-060 ISSN O7449771 VOLUME 60 NUMBER 3 July-September 2003 President’s Message Gene Mayer I began composing this I met PNR Trustee Roger Presidents Message 1 message in mid-June prior to Ferris on a Sunday afternoon Made in the PCR 3 leaving for Dayton, Ohio to prototype tour and he advised BOT Report 4 attend my niece’s wedding and me that the meeting was over in Designing Comfortable Layout continuing on to Toronto, one day. Roger, Stan Ames of Spaces 5 Canada for the NMRA national NER and Ray DeBlieck said the Editor’s Notebook 6 convention. I was concerned Board of Trustees worked Impressions of Convention 8 about what the Board of together and reached several View from the Left Seat 9 Trustees (BOT) compromises. The PCR Leadership Conf 10 would do · PCR needs to develop BOT adopted the Model RR’ing Is Fun 11 concerning the an educational program new NMRA long- Operations SIG 12 proposed and specifically assign range plan and Coast Division Report 16 administrative mentors to advise and approved the GATS Staffing 17 reorganization assist new and existing proposed new Napa Wine Train 18 and single members and modelers. single Achievement Program 20 membership. Divisions should membership. I sat PCR ‘04 Clinics 21 Our PCR Yahoo emphasize advanced at the same table Tales of the SCN 22 Groups Internet planning and as NMRA Modeling Sawmills 24 messages have notification of meeting president Alan Golden State/East Bay 27 been full of dates. Pollock during the S Scale in Review 28 member Layout Design Non Rail Activities 30 comments · PCR should create SIG banquet and New PCR members 31 concerning the subdivisions in remote he is very PCR Convention Registration future of areas to provide more optimistic Form 32 NMRA and the local activities. -

Thirsty Eel Oct. 11-Corrections

1 THE THIRSTY EEL: SUMMER AND WINTER FLOW THRESHOLDS THAT TILT THE EEL 2 RIVER OF NORTHWESTERN CALIFORNIA FROM SALMON-SUPPORTING TO 3 CYANOBACTERIALLY-DEGRADED STATES 4 5 In press, Special Volume, Copeia: Fish out of Water Symposium 6 Mary E. Power1, 7 Keith Bouma-Gregson 2,3 8 Patrick Higgins3, 9 Stephanie M. Carlson4 10 11 12 13 14 1. Department of Integrative Biology, Univ. California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720; Email: 15 [email protected] 16 17 2. Department of Integrative Biology, Univ. California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720; Email: 18 [email protected]> 19 20 3. Eel River Recovery Project, Garberville CA 95542 www.eelriverrecovery.org; Email: 21 [email protected] 22 23 4. Environmental Sciences, Policy and Management, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 24 94720; Email: [email protected] 25 26 27 Running head: Discharge-mediated food web states 28 29 Key words: cyanobacteria, discharge extremes, drought, food webs, salmonids, tipping points 30 31 Although it flows through regions of Northwestern California that are thought to be relatively well- 32 watered, the Eel River is increasingly stressed by drought and water withdrawals. We discuss how critical 33 threshold changes in summer discharge can potentially tilt the Eel from a recovering salmon-supporting 34 ecosystem toward a cyanobacterially-degraded one. To maintain food webs and habitats that support 35 salmonids and suppress harmful cyanobacteria, summer discharge must be sufficient to connect mainstem 36 pools hydrologically with gently moving, cool base flow. Rearing salmon and steelhead can survive even 37 in pools that become isolated during summer low flows if hyporheic exchange is sufficient. -

Geology and Ground-Water Features of the Eureka Area Humboldt County, California

Geology and Ground-Water Features of the Eureka Area Humboldt County, California By R, E. EVENSON GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1470 Prepared in cooperation with the California Department of Water Resources UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1959 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. S EATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U. S. Geological Survey Library has cataloged this publication as follows: Evenson, Robert Edward, 1924- Geology and ground-water features of the Eureka area, Humboldt County, California. Prepared in cooperation with the California Dept. of Water Eesources. Washing ton, U. S. Govt. Print. Off., 1959 iv, 80 p. maps, diagrs., tables. 25 cm. (U. S. Geological Survey Water-supply paper 1470) Part of illustrative matter fold. col. in pocket. Bibliography: p. 77. 1. Water-supply California Humboldt Co. 2. Water, Under ground California Humboldt Co. i. Title: Eureka area, Hum boldt County, California. (Series) TC801.U2 no. 1470 551.490979412 GS 59-169 copy 2. GB1025.C2E9 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. CONTENTS Page Abstract___-_____-__--_--_-_-_________-__--_--_-_-______ ___ 1 Introduction._____________________________________________________ 2 Purpose and scope of the work________ _________________________ 2 Location and extent of the area_______________-_-__-__--________ 3 Previous work_______________________________________________ 3 Well-numbering system________________________________________ -

FC TTS Report 2017

Francis Creek Annual Suspended Sediment Yield Turbidity Threshold Sampling Summary Report Hydrologic Year 2017 Site FRC – 1099 Van Ness Avenue Ferndale, California A collaborative project between Humboldt County Resource Conservation District County of Humboldt City of Ferndale State Coastal Conservancy Ducks Unlimited California Department of Water Resources National Marine Fisheries Service Natural Resources Conservation Service California Department of Fish and Wildlife Wildlife Conservation Board U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service For the Salt River Ecosystem Restoration Project By Clark Fenton 8-2-17 final Francis Creek HY 2017 Annual Report Page 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction Salt River Implementation Monitoring Site FRC map Turbidity Threshold Sampling HY 2017 stage / turbidity plots 2. Francis Creek 2017 Suspended Sediment Annual Load Francis Creek HY 2017 suspended sediment quantities Annual Suspended Sediment load / yield summary table 2008 to 2017 Sarah Wilson Report Storm Load Summary Table - Hydrologic Year 2017 3. Large storm events Hydrologic Year 2017 HY 2017 largest storm turbidity / stage plot 4.Suspended Sediment % Sand Fraction Analysis Hydrologic Year 2017 5.Francis Creek Stream Channel Aggradation Surveys 2007 to 2016 6. Francis Creek Ranch Slide – March 2011 CGS Report Suspended Sediment Yields 7. Field & Lab Operations Hydrologic Year 2017 Methods – Equipment – Challenges Discharge Measurements - Francis Creek Discharge Rating Curve 8. Summary 8. References / Bibliography 9. Appendices – Data CD Appendix 1 – S. Wilson Suspended Sediment Load Reports FRC HY 2007 to HY 2017 Appendix 2 – Suspended Sediment Concentration Data FRC HY 2007 to HY 2017 Appendix 3 – Discharge Data Francis Creek HY 2007 to HY 2017 Appendix 4 – Standard Operating Procedures HY 2007 to HY 2017 Appendix 5 – Turbidity Threshold Sampling Data Files FRC HY 2007 to HY 2017 Appendix 6 – HY 2007 to HY 2017 Raw Data Appendix 7 – CGS Francis Creek Ranch Slide Report / Salt River EIR Francis Creek HY 2017 Annual Report Page 2 1. -

Roots of Motive Power, Highline, April 2004, Volume 22, No. 1

IIRVINE AND MUIR’S BAECHTEL CREEK OPERATION-PAGE 4 GARY KNIVILA COLLECTION: A PERSONAL PERSPECTIVE OF THE UNION LUMBER COMPANY LOGGING WOODS-PAGE 24 ROOTS BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETINGS The Roots Board of Directors established a regular schedule of meetings for 2004. Meetings will be held on the second Thursday of odd numbered months. Meetings are scheduled to begin at 6:00 PM. The schedule for the rest of the year is: May 13; July 8; September 9; November 11. Members and volunteers are welcome to attend these meetings. Meeting sites can be determined by call- ing Chris Baldo, (days) at 707-459-4549. COVER PHOTO: A ULCO Off-highway truck heads to the mill at Usal through a cathedral grove of redwoods. The white GMC 3/4 ton pickup belonged to Gary Knivila. ROOTS OF MOTIVE POWER, INC. 2003-2004 This newsletter is the official publication of Officers and Directors Roots of Motive Power, Inc., an organization dedi- cated to the preservation and restoration of logging President - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Chris Baldo and railroad equipment representative of Califor- Vice President - - - - - - - - - - - Wes Brubacher nia’s North Coast region, 1850s to the present. Secretary - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Joan Daniels Membership $25.00 annually; regular members vote Corresponding Secretary - - - - - Dian Crayne for officers and directors who decide the general Treasurer/Director - - - - - - - - Chuck Crayne policy and direction of the association. Roots’ mail- Librarian/Director - - - - - - - - - - Bruce Evans ing address is: ROOTS OF MOTIVE POWER, Director - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Vrain Conley INC. PO Box 1540, Willits, CA 95490. Roots of Director - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Kirk Graux Motive Power displays are located near the Mendo- Director - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - George Bush cino County Museum, 400 East Commercial St, Director - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - John Bradley Willits, CA. -

Gyppo Logging in Humboldt County: a Boom-Bust Cycle on the California Forest Frontier

GYPPO LOGGING IN HUMBOLDT COUNTY: A BOOM-BUST CYCLE ON THE CALIFORNIA FOREST FRONTIER by Kenneth Frederick Farnsworth, III A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts In Social Science: Geography July, 1996 GYPPO LOGGING IN HUMBOLDT COUNTY: A BOOM-BUST CYCLE ON THE CALIFORNIA FOREST FRONTIER by Kenneth Frederick Farnsworth, III Approved by: Joseph S. Leeper, Major Professor Paul W. Blank, Committee Member Christopher S. Haynes, Committee Member Gerald Sattinger, Graduate Coordinator, SBSS John P. Turner, Dean for Research and Graduate Studies ABSTRACT GYPPO LOGGING IN HUMBOLDT COUNTY: A BOOM-BUST CYCLE ON THE CALIFORNIA FOREST FRONTIER by Kenneth Frederick Farnsworth, III Discusses the rise and decline of the gyppo (small contract) logging and sawmill industry in Humboldt County, California between 1945 and 1965. Historical discussion of the role of large redwood companies, and transportation systems which they used, prior to 1945. Explains the land ownership patterns, resource diffusion of the primary resource (Douglas-fir), and emerging logging technology. This allowed gyppo contractors to rival the production of the established industry. Conclusion: too many mills harvested excessive amounts of old-growth Douglas-fir during the 1950's. Tightening log supply situation during the 1960's and 1970's drove most gyppo mills out of business, and reduced the employment potential of the forest products industry. Gyppo logging continues to be somewhat viable, working individual contracts for large, integrated forest products companies. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to a few people who have been influential and helpful during the construction of my thesis. -

Eel River Recovery Project Rose Grassroots 2018 Final Report Lower Eel River Salmon Parkway: Restoration, Recreation and Education

Eel River Recovery Project Rose Grassroots 2018 Final Report Lower Eel River Salmon Parkway: Restoration, Recreation and Education By Pat Higgins and Sal Steinberg for ERRP April 30, 2019 Eel River Recovery Project Rose Grassroots 2018 Final Report Lower Eel River Salmon Parkway: Restoration, Recreation and Education The Rose Foundation awarded the Eel River Recovery project a Grassroots grant: Lower Eel River Salmon Parkway - Restoration, Recreation and Education in June 2018. This grant was performed from August 2018 through January 2019 and tremendous strides were made towards achieving goals in terms of planning for adult Chinook salmon habitat improvement, promoting a river-side trail, and in connecting with Native American youth and sparking their interest in science and ecology. Accomplishments are reported by key deliverable. Restoration: Fostering Collaboration for Lower Eel River Habitat Improvement Eric Stockwell is a river and ocean kayak guide and a long-time Eel River Recovery Project (ERRP) volunteer. As a native of the lower Eel River, he has seen the river’s decline and feels passionate about restoring the area so that it can once again safely support the early run of the magnificent fall Chinook salmon. Eric began floating the river in a kayak and on stand-up paddleboard (SUP) in late August and visited the river daily until Thanksgiving. What he discovered was that half of the lower Eel River had been diverted around an island in the previous winter high water leaving only one salmon holding pool in a four-mile reach, and long, shallow riffles where salmon could strand when moving upstream. -

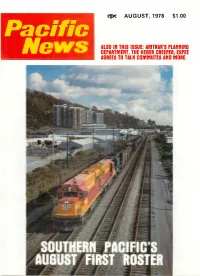

·Pacilic Ne S ALSO in THIS ISSUE: AMTRAK's Planning Department, the HEBER CREEPER, ESPEE AGREES to TALK COMMUTES and MORE

· . cpc AUGUST,1978 $1.00 ·Pacilic Ne s ALSO In THIS ISSUE: AMTRAK'S PLAnninG DEPARTMEnT, THE HEBER CREEPER, ESPEE AGREES TO TALK COMMUTES AnD MORE. ��� SOUTHERN PACIFIC BAY AREA STEAM HARRE W. DEMORO Here is a collection of vintage photographs of the vast Southern Pacific steam operations in the ever-popular San Francisco Bay Area, just as these locomotives appeared in over ninety years of steam activity from the early diamond stackers to giant cab forwards and the fabled Oaylight locomotives. Photographers and collectors featured in this book include Ralph W. Demoro, D. S. Richter, Vernon J. Sappers, Waldemar Sievers and Ted Wurm. The book includes data on Southern Pacific steam locomotive types, and a lengthy general history of the railroad's steam operations in the San Francisco Bay Area that serves as the center of this look at steam-powered railroading. SPECIAL PREPUBLICA TlON OFFER This offer expires November 1, 1978 $15.00 Plus tax, of course, in California * Hardbound with a full-color dust jacket and 136 big 8'hx11" pages * Over 160 steam photographs * San Francisco Bay Area track map * SP Bay Area history * Locomotive data * CHATHAM PUBLISHING COMPANY Post Office Box 283 Burlingame, California 94010 Use convenient order blank on back cover. You may. of course, charge all of your book orders. BEARCAT® SCANNERS BEARCATTING PUTS YOU THERE BEARCAT® The incredible Bearcat® radio scanners bring railroad radio action right into your living room, den, automobile, SCANNERS whatever. Hear all the ra ilroad radio activity in your area THE IDEAL MODELS FOR tonight - do not wait another day. -

4.10 Eel Planning Unit Action Plan, Humboldt County CWPP Final

HUMBOLDT COUNTY COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN, 2019 EEL PLANNING UNIT ACTION PLAN Eel River. Photo: A River’s Last Chance (documentary, 2017). Chapter 4.10: Eel Planning Unit Action Plan HUMBOLDT COUNTY COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN, 2019 Table of Contents – Eel Planning Unit Action Plan 4.10 Eel Planning Unit Action Plan 4.10.1 Eel Planning Unit Description ............................................................................................ 4.10-1 4.10.2 Eel Assets and Values at Risk ............................................................................................. 4.10-1 4.10.3 Eel Wildfire Environment .................................................................................................. 4.10-3 4.10.4 Eel Fire Protection Capabilities.......................................................................................... 4.10-6 4.10.5 Eel Evacuation ................................................................................................................... 4.10-8 4.10.6 Eel Community Preparedness ........................................................................................... 4.10-9 4.10.7 Eel Local Wildfire Prevention Plans ................................................................................. 4.10-10 4.10.8 Eel Community Identified Potential Projects .................................................................. 4.10-13 4.10.9 Eel Action Plan ................................................................................................................. 4.10-15