Rethinking World War I Occupation, Liberation, and Reconstruction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Les Monuments Aux Morts De La Grande Guerre Dans Le Nord-Pas-De-Calais

MOSAÏQUE, revue de jeunes chercheurs en SHS – Lille Nord de France – Belgique – n° 14, décembre 2014 Matthias MEIRLAEN Témoins de mémoires spécifiques : les monuments aux morts de la Grande Guerre dans le Nord-Pas-de-Calais Notice Biographique Matthias Meirlaen est docteur de l’université de Louvain (KU Leuven, Belgique), avec un travail portant sur l’émergence de l’enseignement de l’histoire dans les Pays-Bas méridionaux aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles. Actuellement, il est Post-doctorant à l’Institut de Recherches Historiques du SePtentrion (IRHiS) de l’Université Lille 3 (France). Il y conduit un Projet de recherches intitulé « Retracer la Grande Guerre » sous la direction d’Élise Julien. Dans son contenu, le Projet ambitionne de s’attarder sur l’ensemble des phénomènes de la mémoire de la Première Guerre mondiale dans la région Nord-Pas-de-Calais. Résumé Dans l’entre-deux-guerres, un vaste mouvement commémoratif se développe. Presque chaque commune de France commémore alors ses morts tombés Pendant la Grande Guerre. Dans la majorité des communes, les manifestations en l’honneur des morts se déroulent autour de monuments érigés Pour l’occasion. cet article examine les représentations Portées Par les monuments communaux de la Première Guerre mondiale dans la région Nord-Pas-de-Calais. Cette région constitue du Point de vue de la guerre un esPace charnière spécifique. APrès les batailles d’octobre 1914, elle est partagée pour quatre années en trois zones distinctes : une zone de front, une zone occupée et une zone libre. L’article cherche à voir si les rePrésentations Portées Par les monuments aux morts de l’entre-deux- guerres diffèrent dans les trois secteurs concernés. -

Guide Des Sources Sur La Première Guerre Mondiale Aux A.D

GUIDE DES SOURCES SUR LA PREMIERE GUERRE MONDIALE AUX ARCHIVES DEPARTEMENTALES DE LA SOMME ARCHIVES DEPARTEMENTALES DE LA SOMME AMIENS — OCTOBRE 2015 Illustration de couverture : carte de correspondance militaire (détail), cote 99 R 330935. Date de dernière mise à jour du guide : 13 octobre 2015. 2 Table des matières abrégée Une table des matières détaillée figure à la fin du guide. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................... 5 GUIDE........................................................................................................................................ 10 K - LOIS, ORDONNANCES, ARRETES ................................................................................................ 12 3 K - Recueil des actes administratifs de la préfecture de la Somme (impr.) .................................... 12 4 K - Arrêtés du préfet (registres)....................................................................................................... 12 M - ADMINISTRATION GENERALE ET ECONOMIE ........................................................................... 13 1 M - Administration generale du département.................................................................................. 13 2 M - Personnel de la préfecture, sous-préfectures et services annexes.......................................... 25 3 M - Plébisistes et élections............................................................................................................. -

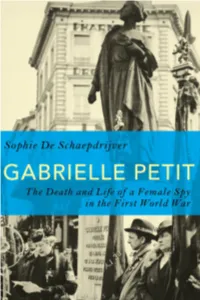

Gabrielle Petit

GABRIELLE PETIT i ii GABRIELLE PETIT THE DEATH AND LIFE OF A FEMALE SPY IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR S o p h i e D e S c h a e p d r i j v e r Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc iii Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Sophie De Schaepdrijver, 2015 Sophie De Schaepdrijver has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author. British Library Cataloguing- in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-1-4725-9087-9 PB: 978-1-4725-9086-2 ePDF: 978-1-4725-9088-6 ePub: 978-1-4725-9089-3 Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Schaepdrijver, Sophie de. Gabrielle Petit : the death and life of a female spy in the First World War / Sophie De Schaepdrijver. -

Revival After the Great War Rebuild, Remember, Repair, Reform

Revival after the Great War Rebuild, Remember, Repair, Reform Edited by Luc Verpoest, Leen Engelen, Rajesh Heynickx, Jan Schmidt, Pieter Uyttenhove, and Pieter Verstraete LEUVEN UNIVERSITY PRESS Published with the support of the KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access, the City of Leuven and LUCA School of Arts Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). © 2020 Selection and editorial matter: Luc Verpoest, Leen Engelen, Rajesh Heynickx, Jan Schmidt, Pieter Uyttenhove, and Pieter Verstraete © 2020 Individual chapters: The respective authors This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non- Derivative 4.0 International Licence. The license allows you to share, copy, distribute, and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Luc Verpoest, Leen Engelen, Rajesh Heynickx, Jan Schmidt, Pieter Uyttenhove, and Pieter Verstraete (eds.). Revival after the Great War: Rebuild, Remember, Repair, Reform. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ISBN 978 94 6270 250 9 (Paperback) ISBN 978 94 6166 354 2 (ePDF) ISBN 978 94 6166 355 9 (ePUB) https://doi.org/10.11116/9789461663542 D/2020/1869/60 NUR: 648 Layout: Friedemann Vervoort Cover design: Anton Lecock Cover illustration: A family -

1 Memorials to French Colonial Soldiers from the Great War Robert

1 Memorials to French Colonial Soldiers from the Great War Robert Aldrich, University of Sydney On 25 June 2006, at Verdun and on the ninetieth anniversary of the battle that took place there, President Jacques Chirac unveiled a memorial to Muslim soldiers who fought in the French armies during the First World War. Paying tribute to the French soldiers who died at Verdun – and also acknowledging the German losses – Chirac stated: ‘Toutes les provinces de France sont à Verdun. Toutes les origines, aussi. 70.000 combattants de l’ex-Empire français sont morts pour la France entre 1914 et 1918. Il y eut dans cette guerre, sous notre drapeau, des fantassins marocains, des tirailleurs sénégalais, algériens et tunisiens, des soldats de Madagascar, mais aussi d’Indochine, d’Asie ou d’Océanie’. Chirac did not dwell on the service of the colonial soldiers, though the only two whom he cited by name, Bessi Samaké and Abdou Assouman, were Africans who distinguished themselves in the taking of the Douaumont fort, but the event was important both for the anciens combattants and their families and communities, and for a French public that has often known or thought little about the military contributions of those whom it colonised.1 With the building of a monument to the Muslim soldiers, an ambulatory surrounding a kouba, according to Le Monde, the inauguration also gave Verdun ‘le statut de haut lieu de la mémoire musulmane de France’.2 In moving terms, the rector of the Paris mosque, Dalil Boubakeur, added of the battlefields where many Muslim soldiers had died, morts pour la France, ‘C’est là que l’Islam de France est né. -

Conflict and Commemoration in France After the First World War

Mort pour la France: conflict and commemoration in France after the First World War Article (Unspecified) Edwards, Peter (2000) Mort pour la France: conflict and commemoration in France after the First World War. University of Sussex Journal of Contemporary History (1). pp. 1-11. This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/1748/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk 1 'Mort pour la France': Conflict and Commemoration in France after the First World War Peter Edwards The commemoration of wars, battles, and their fallen soldiers pre-dates the First World War in Europe and America. -

The Twentieth Century Society

Photo of Monument aux Morts des Armées de Champagne, Ferme de Navarin © Gavin Stamp WAR CEMETERIES IN CHAMPAGNE & ARGONNE The first two tours examining the architectural consequences of the Great War of 1914- 1918 are based on Arras and Ypres and look primarily at the work of the Imperial War Graves Commission along the line of the Western Front that was largely manned by British troops. This tour, based on Reims, looks further east, to Champagne and the Argonne and the section of the Western Front which was held by the French army for most of the war. It includes two notorious sectors: the Chemin des Dames and Verdun. Although we shall see a few British cemeteries and two of the smaller and less distinguished Memorials to the Missing, most of the cemeteries and memorials we will visit are French and American, as it was to this part of the Front that the first American troops were sent in after the United States declared war on Germany in 1917. The areas we are visiting saw fighting from the beginning to the end of the war. the initial German invasion which swept through Belgium and France towards Paris in the Autumn of 1914 was halted by the First Battle of the Marne, well south of Reims. The Germans then retreated and, in a series of outflanking manoeuvres, both sides dug in, with the Germans usually creating defensive positions on higher ground. Unfortunately for the French, the front line ran just north of Soissons, Reims and Verdun, leaving the two former cities subject to continual bombardment. -

Une Base De Données Sur Les Monuments Aux Morts : Histoire Concrète Et Valorisation Numérique

In Situ Revue des patrimoines 25 | 2014 Le patrimoine de la Grande Guerre Une base de données sur les monuments aux morts : histoire concrète et valorisation numérique Martine Aubry and Matthieu de Oliveira Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/insitu/11551 DOI: 10.4000/insitu.11551 ISSN: 1630-7305 Publisher Ministère de la Culture Electronic reference Martine Aubry and Matthieu de Oliveira, « Une base de données sur les monuments aux morts : histoire concrète et valorisation numérique », In Situ [Online], 25 | 2014, Online since 30 January 2015, connection on 01 July 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/insitu/11551 ; DOI : https://doi.org/ 10.4000/insitu.11551 This text was automatically generated on 1 July 2020. In Situ Revues des patrimoines est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Une base de données sur les monuments aux morts : histoire concrète et valori... 1 Une base de données sur les monuments aux morts : histoire concrète et valorisation numérique Martine Aubry and Matthieu de Oliveira 1 « Passant, souviens-toi ! »1. Dans un pays comme la France, une telle injonction ne manque pas d’être réitérée presque à chaque coin de rue de chaque commune. Elle vise à entretenir le souvenir de ceux qui ont fait le sacrifice de leur vie pour le pays et se trouve matérialisée dans une multiplicité de monuments commémoratifs. Le plus visible, le plus fréquent est sans conteste le monument aux morts, symbole des conflits passés et rappel des morts pour la patrie, périodiquement célébrés lors de cérémonies officielles du 11 Novembre. -

Manipulating the Metonymic the Politics of Civic Identity and the Bristol Cenotaph, 1919 - 1932

Gough, P.J. and Morgan, S.J. (2004) Manipulating the Metonymic : the politics of civic identity and the Bristol Cenotaph, 1919 – 1932, Journal of Historical Geography, 30 (2004) pp. 665-684 ISSN 0305-7488 Manipulating the Metonymic The politics of civic identity and the Bristol Cenotaph, 1919 - 1932 Abstract The city of Bristol was one of the last major cities in Great Britain to unveil a civic memorial to comemmorate the Great War 1914 – 1918. After Leicester (1925), Coventry (1927) and Liverpool (1930) Bristol’s Cenotaph was unveiled in 1932, fourteen years after the Armistice. During that lapse, its location, source of funding, and commemorative function were the focus of widespread disagreement and division in the city. This paper examines the nature of these disputes. The authors suggest that the tensions in locating a war memorial may have their origins in historic enmities between political and religious factions in the city. By examining in detail the source and manifestations of these disputes the authors offer a detailed exemplar of how memory is shaped and controlled in British urban spaces Keywords Bristol Cenotaph Historiography War memorials Contested spaces Introduction The Cenotaph as a form is, as Sergiusz Michalski observes, metonymic. Whereas nineteenth century monuments had tended towards the allegorical or metaphoric (1) or had stood as portraits of the good and the great, the twentieth century Cenotaph, along with the equally novel Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, stood as a singular abstraction of mass death. Both these memorial forms may be seen as anti-individualistic, or as Michalski further posits, ‘democratic.’ (2) These monuments do not celebrate individual heroicism or leadership, rather, they mourn the common man, for in this project the foot soldier is equal to the field marshal. -

Des Monuments Aux Morts Entre Laïcité Et Ferveur Religieuse : Un Patrimoine Hors-La-Loi ?

In Situ Revue des patrimoines 25 | 2014 Le patrimoine de la Grande Guerre Des monuments aux morts entre laïcité et ferveur religieuse : un patrimoine hors-la-loi ? Claude Dupuis Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/insitu/11326 DOI: 10.4000/insitu.11326 ISSN: 1630-7305 Publisher Ministère de la Culture Electronic reference Claude Dupuis, « Des monuments aux morts entre laïcité et ferveur religieuse : un patrimoine hors-la- loi ? », In Situ [Online], 25 | 2014, Online since 29 December 2014, connection on 25 June 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/insitu/11326 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/insitu.11326 This text was automatically generated on 25 June 2020. In Situ Revues des patrimoines est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Des monuments aux morts entre laïcité et ferveur religieuse : un patrimoine h... 1 Des monuments aux morts entre laïcité et ferveur religieuse : un patrimoine hors-la-loi ? Claude Dupuis Des monuments pour se souvenir 1 Les monuments aux morts revêtent deux fonctions principales : ils sont à la fois la tombe symbolique de ceux qui ont défendu la Nation et ils désignent un lieu des commémorations publiques. Dans ses formes les plus élémentaires mais très usitées de la stèle ou de l’obélisque, peu, voire aucun élément de nature artistique donc esthétique n’interfère entre le monument et ceux qui se souviennent. La seule présence des noms des disparus impose une certaine neutralité du message délivré par l’objet lui-même. La présence du soldat de bronze, issu des Établissements métallurgiques Durenne, des fonderies du Val d’Osne ou d’ailleurs, marque une étape vers une signification ou un message plus explicite délivrés par les commanditaires aux populations survivantes. -

Hi3408 List 1 France and the First World War Handbook 2

List 1: France and FWW Handbook 2: 2013/14 1 HI3408 LIST 1 FRANCE AND THE FIRST WORLD WAR HANDBOOK 2 (Hilary term) Ossuary of Douaumont, Verdun, built 1920-1932 by private French and international donations. Graves, with the recently-built Islamic shrine for colonial soldiers in the distance. Professor John Horne Department of History, Trinity College Dublin 2013-2014 This Handbook is available on the History School website List 1: France and FWW Handbook 2: 2013/14 2 1. Programme Week 1: The other France. Life under German occupation. Other occupations during the Great War. Lecture: Occupation and resistance during the Great War Seminar: first hour: documents second hour: class themes (i) life in occupied France and/orBelgium (ii) German policy in occupied eastern Europe. Week 2: Home fronts. The social and psychological impact of the war on civilians Lecture: Living standards during the First World War: comparisons. Seminar: first hour: documents second hour: class themes (i) The importance of food (France and Germany) (ii) Moral economies of war Week 3: Crises and endgame: military events, 1917-18. Lecture: The military ‘learning curve’: armies on the western front, 1917-18 first hour: documents second hour: class themes (i) How series were the mutinies in the French army, 1917 (ii) Why did the allies win in 1918? Week 4: Colonial empires and the war. Lecture: Colonial Empires in the Great War. Seminar: first hour : documents second hour : class themes (i) What impact did colonial soldiers and workers have in France? (ii) Did the war change empires? SECOND COURSE ESSAY [ESSAY 3] DUE (TO JH) MONDAY 3 FEBRUARY Week 5: Pacifism and opposition to the war Lecture: The languages of pacifism. -

Centenary (Madagascar) | International Encyclopedia of The

Version 1.0 | Last updated 24 February 2021 Centenary (Madagascar) By Arnaud Leonard In Madagascar, between 2014 and 2018, there were many initiatives to commemorate Malagasy participation in the Great War: exhibitions, monument inaugurations, ceremonies, conferences, etc. However, these have often presented a stereotypical vision of war, which had little impact on public opinion. Despite the historical research available online, the myths of cannon fodder and the claims of blood debt have been revived. Table of Contents 1 Introduction 2 A Large and Very Temporary Exhibition in the Capital City 3 An Exhibition Well Covered in the Press 4 Exhibitions in the Provinces 5 Inaugurations of Steles Commemorating the First Embarkation of the Tirailleurs 6 A School Project: the Monument for Rafiringa 7 Evolution of the Remembrance Ceremonies 8 The Ceremonies around the National War Memorial in Antananarivo 9 Historical Research and Archival Endeavour 10 A Limited Distribution of Letters, Memoirs, Documentaries and Comic Strips 11 Conclusion Notes Selected Bibliography Citation Introduction During the First World War, more than 40,000 soldiers and workers were recruited in Madagascar. The largest island in the Indian Ocean, conquered by the French in 1896, had a population of about 3 million. 10 percent of these tirailleurs died during or just after the conflict. The French authorities only deployed these troops to Europe and the Mediterranean (Greece) at a late stage: the first major waves of recruitment took place in August 1916. In some cases, Malagasies volunteered in the hope of securing French citizenship, but the vast majority of tirailleurs were poor rice farmers, indebted workers and freed slaves, pushed by the administration and its promise of significant war pay and family benefits.