Conflict and Commemoration in France After the First World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War One: the Deaths of Those Associated with Battle and District

WORLD WAR ONE: THE DEATHS OF THOSE ASSOCIATED WITH BATTLE AND DISTRICT This article cannot be more than a simple series of statements, and sometimes speculations, about each member of the forces listed. The Society would very much appreciate having more information, including photographs, particularly from their families. CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 The western front 3 1914 3 1915 8 1916 15 1917 38 1918 59 Post-Armistice 82 Gallipoli and Greece 83 Mesopotamia and the Middle East 85 India 88 Africa 88 At sea 89 In the air 94 Home or unknown theatre 95 Unknown as to identity and place 100 Sources and methodology 101 Appendix: numbers by month and theatre 102 Index 104 INTRODUCTION This article gives as much relevant information as can be found on each man (and one woman) who died in service in the First World War. To go into detail on the various campaigns that led to the deaths would extend an article into a history of the war, and this is avoided here. Here we attempt to identify and to locate the 407 people who died, who are known to have been associated in some way with Battle and its nearby parishes: Ashburnham, Bodiam, Brede, Brightling, Catsfield, Dallington, Ewhurst, Mountfield, Netherfield, Ninfield, Penhurst, Robertsbridge and Salehurst, Sedlescombe, Westfield and Whatlington. Those who died are listed by date of death within each theatre of war. Due note should be taken of the dates of death particularly in the last ten days of March 1918, where several are notional. Home dates may be based on registration data, which means that the year in 1 question may be earlier than that given. -

WAR MEMORIALS: TEN QUESTIONS for HISTORIANS Author(S): K. S. Inglis Source: Guerres Mondiales Et Conflits Contemporains, No

WAR MEMORIALS: TEN QUESTIONS FOR HISTORIANS Author(s): K. S. Inglis Source: Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains, No. 167, LES MONUMENTS AUX MORTS DE LA PREMIÈRE GUERRE MONDIALE (Juillet 1992), pp. 5-21 Published by: Presses Universitaires de France Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25730853 Accessed: 01-11-2015 00:30 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25730853?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Presses Universitaires de France is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 89.179.117.36 on Sun, 01 Nov 2015 00:30:37 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions WAR MEMORIALS: TEN QUESTIONS FOR HISTORIANS* - I WHY HAVE HISTORIANS NEGLECTED THEM? They are among the most visible objects in the urban and rural land scapes of many countries: a characteristically modern addition to the world's stock ofmonuments. Expressing as they do their creators' thoughts and feelings about war, nationality and death, these artefacts constitute a vast and rewarding resource forhistorians. -

Les Monuments Aux Morts De La Grande Guerre Dans Le Nord-Pas-De-Calais

MOSAÏQUE, revue de jeunes chercheurs en SHS – Lille Nord de France – Belgique – n° 14, décembre 2014 Matthias MEIRLAEN Témoins de mémoires spécifiques : les monuments aux morts de la Grande Guerre dans le Nord-Pas-de-Calais Notice Biographique Matthias Meirlaen est docteur de l’université de Louvain (KU Leuven, Belgique), avec un travail portant sur l’émergence de l’enseignement de l’histoire dans les Pays-Bas méridionaux aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles. Actuellement, il est Post-doctorant à l’Institut de Recherches Historiques du SePtentrion (IRHiS) de l’Université Lille 3 (France). Il y conduit un Projet de recherches intitulé « Retracer la Grande Guerre » sous la direction d’Élise Julien. Dans son contenu, le Projet ambitionne de s’attarder sur l’ensemble des phénomènes de la mémoire de la Première Guerre mondiale dans la région Nord-Pas-de-Calais. Résumé Dans l’entre-deux-guerres, un vaste mouvement commémoratif se développe. Presque chaque commune de France commémore alors ses morts tombés Pendant la Grande Guerre. Dans la majorité des communes, les manifestations en l’honneur des morts se déroulent autour de monuments érigés Pour l’occasion. cet article examine les représentations Portées Par les monuments communaux de la Première Guerre mondiale dans la région Nord-Pas-de-Calais. Cette région constitue du Point de vue de la guerre un esPace charnière spécifique. APrès les batailles d’octobre 1914, elle est partagée pour quatre années en trois zones distinctes : une zone de front, une zone occupée et une zone libre. L’article cherche à voir si les rePrésentations Portées Par les monuments aux morts de l’entre-deux- guerres diffèrent dans les trois secteurs concernés. -

Guide to Manitoba Memorial Types

GUIDE TO MANITOBA MEMORIAL TYPES War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy GUIDE TO MANITOBA MEMORIAL TYPES he memorials honouring Manitoba’s dead of World War I are a profound historical legacy. They are also a major artistic achievement. This section of the study of Manitoba war memorials explores the Tmost common types of memorials with an eye to formal considerations – design, aesthetics, materials, and craftsmanship. For those who look to these objects primarily as places of memory and remembrance, this additional perspective can bring a completely different level of understanding and appreciation, and even delight. Six major groupings of war memorial types have been identified in Manitoba: Tablets Cairns Obelisks Cenotaphs Statues Architectural Monuments Each of these is reviewed in the following entries, with a handful of typical or exceptional Manitoba examples used to illuminate the key design and material issues and attributes that attend the type. Guide to Manitoba Memorial Types 1 War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy Tablets The apparently simple and elemental form of the tablet, also known as a stele (from the ancient Greek, with stelae as the plural), is the most common form of gravesite memorial. Given its popularity and cultural and historical resonance, its use for war memorials is understandable. The tablet is economical—in form and often in cost—but also elegant. And while the simple planar face is capable of conveying a great deal of inscribed information, the very form itself can be seen as a highly abstracted version of the human body – and thus often has a mysterious attractive quality. -

Guide Des Sources Sur La Première Guerre Mondiale Aux A.D

GUIDE DES SOURCES SUR LA PREMIERE GUERRE MONDIALE AUX ARCHIVES DEPARTEMENTALES DE LA SOMME ARCHIVES DEPARTEMENTALES DE LA SOMME AMIENS — OCTOBRE 2015 Illustration de couverture : carte de correspondance militaire (détail), cote 99 R 330935. Date de dernière mise à jour du guide : 13 octobre 2015. 2 Table des matières abrégée Une table des matières détaillée figure à la fin du guide. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................... 5 GUIDE........................................................................................................................................ 10 K - LOIS, ORDONNANCES, ARRETES ................................................................................................ 12 3 K - Recueil des actes administratifs de la préfecture de la Somme (impr.) .................................... 12 4 K - Arrêtés du préfet (registres)....................................................................................................... 12 M - ADMINISTRATION GENERALE ET ECONOMIE ........................................................................... 13 1 M - Administration generale du département.................................................................................. 13 2 M - Personnel de la préfecture, sous-préfectures et services annexes.......................................... 25 3 M - Plébisistes et élections............................................................................................................. -

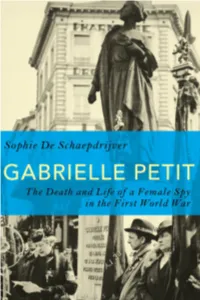

Gabrielle Petit

GABRIELLE PETIT i ii GABRIELLE PETIT THE DEATH AND LIFE OF A FEMALE SPY IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR S o p h i e D e S c h a e p d r i j v e r Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc iii Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Sophie De Schaepdrijver, 2015 Sophie De Schaepdrijver has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author. British Library Cataloguing- in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-1-4725-9087-9 PB: 978-1-4725-9086-2 ePDF: 978-1-4725-9088-6 ePub: 978-1-4725-9089-3 Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Schaepdrijver, Sophie de. Gabrielle Petit : the death and life of a female spy in the First World War / Sophie De Schaepdrijver. -

ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Name (As On

Houses of Parliament War Memorials Royal Gallery, First World War ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Also in Also in Westmins Commons Name (as on memorial) Full Name MP/Peer/Son of... Constituency/Title Birth Death Rank Regiment/Squadron/Ship Place of Death ter Hall Chamber Sources Shelley Leopold Laurence House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Baron Abinger Shelley Leopold Laurence Scarlett Peer 5th Baron Abinger 01/04/1872 23/05/1917 Commander Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve London, UK X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Humphrey James Arden 5th Battalion, London Regiment (London Rifle House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Adderley Humphrey James Arden Adderley Son of Peer 3rd son of 2nd Baron Norton 16/10/1882 17/06/1917 Rifleman Brigade) Lincoln, UK MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) The House of Commons Book of Bodmin 1906, St Austell 1908-1915 / Eldest Remembrance 1914-1918 (1931); Thomas Charles Reginald Thomas Charles Reginald Agar- son of Thomas Charles Agar-Robartes, 6th House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Agar-Robartes Robartes MP / Son of Peer Viscount Clifden 22/05/1880 30/09/1915 Captain 1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards Lapugnoy, France X X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Horace Michael Hynman Only son of 1st Viscount Allenby of Meggido House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Allenby Horace Michael Hynman Allenby Son of Peer and of Felixstowe 11/01/1898 29/07/1917 Lieutenant 'T' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery Oosthoek, Belgium MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Aeroplane over House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Francis Earl Annesley Francis Annesley Peer 6th Earl Annesley 25/02/1884 05/11/1914 -

Revival After the Great War Rebuild, Remember, Repair, Reform

Revival after the Great War Rebuild, Remember, Repair, Reform Edited by Luc Verpoest, Leen Engelen, Rajesh Heynickx, Jan Schmidt, Pieter Uyttenhove, and Pieter Verstraete LEUVEN UNIVERSITY PRESS Published with the support of the KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access, the City of Leuven and LUCA School of Arts Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). © 2020 Selection and editorial matter: Luc Verpoest, Leen Engelen, Rajesh Heynickx, Jan Schmidt, Pieter Uyttenhove, and Pieter Verstraete © 2020 Individual chapters: The respective authors This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non- Derivative 4.0 International Licence. The license allows you to share, copy, distribute, and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Luc Verpoest, Leen Engelen, Rajesh Heynickx, Jan Schmidt, Pieter Uyttenhove, and Pieter Verstraete (eds.). Revival after the Great War: Rebuild, Remember, Repair, Reform. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ISBN 978 94 6270 250 9 (Paperback) ISBN 978 94 6166 354 2 (ePDF) ISBN 978 94 6166 355 9 (ePUB) https://doi.org/10.11116/9789461663542 D/2020/1869/60 NUR: 648 Layout: Friedemann Vervoort Cover design: Anton Lecock Cover illustration: A family -

National World War I Memorial Presentation for Final Approval

U.S. COMMISSION OF FINE ARTS SUBMISSION | SEPTEMBER 19, 2019 National World War I Memorial Presentation for Final Approval Sculptor SABIN HOWARD 1 PRESENTATION CONTENT SUMMARY OF PREVIOUS / UPCOMING PRESENTATIONS • Concept Lighting, Furnishing and Finishes (February 2019) • Response to Walkway, Lighting, and Sculpture Fountain Comments (April 2019) • Interpretation and Detailing (May 2019) • Response to Sculpture and Lighting Comments + Site Security and Final Detailing (July 2019) • Design Recap for Final Approval (anticipated September 2019) PRESENTATION OBJECTIVES (9/19/2019) • Final Approval PRESENTATION OUTLINE • Project Scope and Background • Existing Conditions • Design Summary - Organizing Framework - Balancing Two Works of Art - Memorial Park Design - Memorial Park Program - Interpretive Framework • 1st Tier Commemorative Features - Existing Pershing Memorial - A Soldier’s Journey - Peace Fountain - Sculpture Fountain • 2nd Tier Commemorative Features - Belvedere - Tactile Model - Inscriptions - Flagstaff • 3rd Tier Commemorative Features - Information Poppies • Supporting Elements - Viewing Platform - ADA Accessibility Improvements - Park History Wayside - Lighting - Entry Signage and Site Security Measures - Acknowledgments Panel • Planting - Existing Canopy - Proposed Canopy - Understory 2 PROJECT SCOPE AND BACKGROUND 3 PROJECT SCOPE AND BACKGROUND INTRODUCTION Of the four major wars of the twentieth century, World War I alone has no national memorial in the nation’s capital. More American servicemen were lost in World War I than in the Korean and Vietnam wars combined, with 116,516 lost and 200,000 more wounded. In December 2014, President Obama signed legislation authorizing the U.S. World War I Centennial Commission (WWICC) to establish a new memorial. P.L.113- 291, Section 3091 of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2015 re-designates Pershing Park in the District of Columbia, an existing memorial to General John J. -

The Conservation, Repair and Management of War Memorials

The Conservation, Repair and Management of War Memorials Guidance and best practice on the understanding, assessment, planning and implementation of conservation work to war memorials as well as their ongoing maintenance and protection. www.english-heritage.org.uk/warmemorials FRONT COVER IMAGES: Top Left: Work in progress: Top Right: This differential staining Bottom Left: High pressure Bottom Right: Detail of repainted touching in lettering to enhance the is typical of exposed bronze steam cleaning (DOFF) to remove lettering; there are small holes in legibility of the names. statuary. Most of the surface has degraded wax, paint and loose the incisions that indicate that this © Humphries & Jones developed a natural patination but corrosion products, prior to was originally lead lettering. In most the original bronze colour is visible patination. cases it is recommended that re- Top Middle: The Hoylake and in protected areas. There is also © Rupert Harris Conservation Ltd lettering should follow the design West Kirby memorial has been staining from bird droppings and and nature of the original but the listed Grade II* for two main water run-off. theft of lead sometimes makes but unconnected reasons: it was © Odgers Conservation repainting an appropriate (and the first commission of Charles Consultants Ltd temporary) solution. Sargeant Jagger and it is also is © Odgers Conservation situated in a dramatic setting at Consultants Ltd the top of Grange Hill overlooking Liverpool Bay. © Peter Jackson-Lee 2008 Contents Summary 4 10 Practical -

1 Memorials to French Colonial Soldiers from the Great War Robert

1 Memorials to French Colonial Soldiers from the Great War Robert Aldrich, University of Sydney On 25 June 2006, at Verdun and on the ninetieth anniversary of the battle that took place there, President Jacques Chirac unveiled a memorial to Muslim soldiers who fought in the French armies during the First World War. Paying tribute to the French soldiers who died at Verdun – and also acknowledging the German losses – Chirac stated: ‘Toutes les provinces de France sont à Verdun. Toutes les origines, aussi. 70.000 combattants de l’ex-Empire français sont morts pour la France entre 1914 et 1918. Il y eut dans cette guerre, sous notre drapeau, des fantassins marocains, des tirailleurs sénégalais, algériens et tunisiens, des soldats de Madagascar, mais aussi d’Indochine, d’Asie ou d’Océanie’. Chirac did not dwell on the service of the colonial soldiers, though the only two whom he cited by name, Bessi Samaké and Abdou Assouman, were Africans who distinguished themselves in the taking of the Douaumont fort, but the event was important both for the anciens combattants and their families and communities, and for a French public that has often known or thought little about the military contributions of those whom it colonised.1 With the building of a monument to the Muslim soldiers, an ambulatory surrounding a kouba, according to Le Monde, the inauguration also gave Verdun ‘le statut de haut lieu de la mémoire musulmane de France’.2 In moving terms, the rector of the Paris mosque, Dalil Boubakeur, added of the battlefields where many Muslim soldiers had died, morts pour la France, ‘C’est là que l’Islam de France est né. -

How the United States Used War Memorials and Soldier Poetry to Commemorate the Great War

Memories in stone and ink: How the United States used war memorials and soldier poetry to Commemorate the Great War by Jennifer Madeline Zoebelein B.A., Mary Washington College, 2004 M.A., The University of Charleston and The Military College of South Carolina, 2008 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2018 Abstract War occupies an important place in the collective memory of the United States, with many of its defining moments centered on times of intense trauma. American memory of World War I, however, pales in comparison to the Civil War and World War II, which has led to the conflict’s categorization as a “forgotten” war—terminology that ignores the widespread commemorative efforts undertaken by Americans in the war’s aftermath. In fact, the interwar period witnessed a multitude of memorialization projects, ranging from architectural memorials to literature. It is this dichotomy between contemporary understanding and the reality of the conflict’s aftermath that is at the heart of this study, which seeks to illuminate the prominent position held by the First World War in early twentieth century American society. The dissertation examines three war memorials: the Liberty Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri; the District of Columbia World War Memorial in West Potomac Park, Washington, D.C.; and Kansas State University’s Memorial Stadium in Manhattan, Kansas. The work also analyzes seven volumes of soldier poetry, published between 1916 and 1921: Poems, by Alan Seeger; With the Armies of France, by William Cary Sanger, Jr.; Echoes of France: Verses from my Journal and Letters, March 14, 1918 to July 14, 1919 and Afterwards, by Amy Robbins Ware; The Tempering, by Howard Swazey Buck; Wampum and Old Gold, by Hervey Allen; The Log of the Devil Dog and Other Verses, by Byron H.