The Making of a Memorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War One: the Deaths of Those Associated with Battle and District

WORLD WAR ONE: THE DEATHS OF THOSE ASSOCIATED WITH BATTLE AND DISTRICT This article cannot be more than a simple series of statements, and sometimes speculations, about each member of the forces listed. The Society would very much appreciate having more information, including photographs, particularly from their families. CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 The western front 3 1914 3 1915 8 1916 15 1917 38 1918 59 Post-Armistice 82 Gallipoli and Greece 83 Mesopotamia and the Middle East 85 India 88 Africa 88 At sea 89 In the air 94 Home or unknown theatre 95 Unknown as to identity and place 100 Sources and methodology 101 Appendix: numbers by month and theatre 102 Index 104 INTRODUCTION This article gives as much relevant information as can be found on each man (and one woman) who died in service in the First World War. To go into detail on the various campaigns that led to the deaths would extend an article into a history of the war, and this is avoided here. Here we attempt to identify and to locate the 407 people who died, who are known to have been associated in some way with Battle and its nearby parishes: Ashburnham, Bodiam, Brede, Brightling, Catsfield, Dallington, Ewhurst, Mountfield, Netherfield, Ninfield, Penhurst, Robertsbridge and Salehurst, Sedlescombe, Westfield and Whatlington. Those who died are listed by date of death within each theatre of war. Due note should be taken of the dates of death particularly in the last ten days of March 1918, where several are notional. Home dates may be based on registration data, which means that the year in 1 question may be earlier than that given. -

WAR MEMORIALS: TEN QUESTIONS for HISTORIANS Author(S): K. S. Inglis Source: Guerres Mondiales Et Conflits Contemporains, No

WAR MEMORIALS: TEN QUESTIONS FOR HISTORIANS Author(s): K. S. Inglis Source: Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains, No. 167, LES MONUMENTS AUX MORTS DE LA PREMIÈRE GUERRE MONDIALE (Juillet 1992), pp. 5-21 Published by: Presses Universitaires de France Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25730853 Accessed: 01-11-2015 00:30 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25730853?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Presses Universitaires de France is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 89.179.117.36 on Sun, 01 Nov 2015 00:30:37 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions WAR MEMORIALS: TEN QUESTIONS FOR HISTORIANS* - I WHY HAVE HISTORIANS NEGLECTED THEM? They are among the most visible objects in the urban and rural land scapes of many countries: a characteristically modern addition to the world's stock ofmonuments. Expressing as they do their creators' thoughts and feelings about war, nationality and death, these artefacts constitute a vast and rewarding resource forhistorians. -

Allerdale District War Memorials Transcript

ALLERDALE War Memorials Names Lists Harrington Village Memorial-Transcription ERECTED IN GRATEFUL MEMORY/OF THE MEN OF THIS PARISH/WHO SACRIFICED THEIR LIVES/IN THE GREAT WAR/1914-1918 ERECTED 1925, RE-SITED HERE 2001/RE-DEDICATED BY THE BISHOP OF CARLISLE/THE RIGHT REVEREND GRAHAM DOW/12TH JUNE 2001 WW1 South Face Column 1 S AGNEW/H AMBLER/JC ANDERSON/JN ARNOTT/C ASKEW/F BARKER/L BERESFORD/J BIRD/E BIRD/ED BIRNIE/ RC BLAIR/H BLAIR/W BLAIR Column 2 S BOWES/J BOYLE/W BROWN/JT BROWN/J BYRNE/R BURNS/J CAHILL/M CASSIDY/T CAPE/J CARTER/JH CRANE M DACRE West Face Column 1 JM STAMPER/H TEMPLETON/R TEMPLETON/WH THOMAS/T TINKLER/H TOFT/J TWEDDLE/J TYSON/C UHRIG J WARD/W WARDROP/T WARREN/M WATSON/J WAUGH/J WESTNAGE/A WHITE/G WHITEHEAD Column 2 M WILLIAMSON/E WILSON/H WILSON/J WILSON/W WOODBURN/H WRIGHT/A WYPER North Face Column 1 JR LITTLE/WH MCCLURE/D MCCORD/D MCGEORGE/T MCGLENNON/W MCKEE/A MCCLENNAN/A MCMULLEN/ J MCNICHOLAS/H MASON/W MILLICAN/J MOORE/WH MOORE/G MORTON/J MORTON/J MURPHY/T NEEN/ J O’NEIL Column 2 G PAISLEY/I PARK/W PARKER/JJ PALMER/FH PICKARD/J POOLE/GF PRICE/TP PRICE/R PRITT/A RAE/J RAE H REECE/R RICE/P RODGERS/JW ROBINSON/T SCOTT/W SCRUGHAM/N SIMON/T SPOONER East Face Column 1 Page 1 of 159 H DALTON/JTP DAWSON/G DITCHBURN/E DIXON/NG DOBSON/B DOLLIGAN/W DORAN/M DOUGLAS/H FALCON JJ FEARON/J FEARON/J FERRY/H FLYNN/TH FRAZER/T GILMORE/W GILMORE/T GORRY/J GREENAN Column 2 WJ HALL/WH HARDON/J HARRISON/J HEAD/J HEWSON/TB HEWSON/A HILL/A HODGSON/J HUNTER/TB HUGHES A INMAN/JW INMAN/D JACKSON/W JACKSON/H JEFFREY/G JOHNSTON/J KEENAN WW2 -

Guide to Manitoba Memorial Types

GUIDE TO MANITOBA MEMORIAL TYPES War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy GUIDE TO MANITOBA MEMORIAL TYPES he memorials honouring Manitoba’s dead of World War I are a profound historical legacy. They are also a major artistic achievement. This section of the study of Manitoba war memorials explores the Tmost common types of memorials with an eye to formal considerations – design, aesthetics, materials, and craftsmanship. For those who look to these objects primarily as places of memory and remembrance, this additional perspective can bring a completely different level of understanding and appreciation, and even delight. Six major groupings of war memorial types have been identified in Manitoba: Tablets Cairns Obelisks Cenotaphs Statues Architectural Monuments Each of these is reviewed in the following entries, with a handful of typical or exceptional Manitoba examples used to illuminate the key design and material issues and attributes that attend the type. Guide to Manitoba Memorial Types 1 War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy Tablets The apparently simple and elemental form of the tablet, also known as a stele (from the ancient Greek, with stelae as the plural), is the most common form of gravesite memorial. Given its popularity and cultural and historical resonance, its use for war memorials is understandable. The tablet is economical—in form and often in cost—but also elegant. And while the simple planar face is capable of conveying a great deal of inscribed information, the very form itself can be seen as a highly abstracted version of the human body – and thus often has a mysterious attractive quality. -

Lincolnshire Remembrance Newsletter October 2014

Lincolnshire Remembrance: Memories and Memorials Newsletter October 2014 Project Update: http://www.lincstothepast.com/home/lincolnshire-remembrance/ We still have a lot of work to do adding photographs and information, but over the next few months it should start to become a really useful resource. We would really like you all to check that we have information on your local memorials and please do let us know if there are any we have missed. There will be mistakes so please do let us know if you spot any! I am currently sorting through the memorial photographs with the help of some 'data angels' and I am compiling a list of memorials for which we do not have a good photograph. I will email this to you all as soon as I have a reasonable number so that hopefully we can gain a more complete record of the memorials. Training and Information days for Lincolnshire Remembrance We are running a series of training and information events in October and November. This will finally give us a chance to meet you all and give you a chance to participate in the project. Please do attend if you can; to book a place email me at [email protected] or call on 01522 554959. Lunch will be provided so please let me know if you have any special dietary requirements, or indeed any other special needs. All the events are free of charge and we have tried to choose venues with parking where possible. We can book some more events at other locations if there is sufficient demand – please let us know if you will find it difficult to attend any of the events listed. -

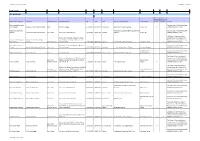

ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Name (As On

Houses of Parliament War Memorials Royal Gallery, First World War ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Also in Also in Westmins Commons Name (as on memorial) Full Name MP/Peer/Son of... Constituency/Title Birth Death Rank Regiment/Squadron/Ship Place of Death ter Hall Chamber Sources Shelley Leopold Laurence House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Baron Abinger Shelley Leopold Laurence Scarlett Peer 5th Baron Abinger 01/04/1872 23/05/1917 Commander Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve London, UK X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Humphrey James Arden 5th Battalion, London Regiment (London Rifle House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Adderley Humphrey James Arden Adderley Son of Peer 3rd son of 2nd Baron Norton 16/10/1882 17/06/1917 Rifleman Brigade) Lincoln, UK MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) The House of Commons Book of Bodmin 1906, St Austell 1908-1915 / Eldest Remembrance 1914-1918 (1931); Thomas Charles Reginald Thomas Charles Reginald Agar- son of Thomas Charles Agar-Robartes, 6th House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Agar-Robartes Robartes MP / Son of Peer Viscount Clifden 22/05/1880 30/09/1915 Captain 1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards Lapugnoy, France X X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Horace Michael Hynman Only son of 1st Viscount Allenby of Meggido House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Allenby Horace Michael Hynman Allenby Son of Peer and of Felixstowe 11/01/1898 29/07/1917 Lieutenant 'T' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery Oosthoek, Belgium MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Aeroplane over House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Francis Earl Annesley Francis Annesley Peer 6th Earl Annesley 25/02/1884 05/11/1914 -

Napoleon's Men

NAPOLEON S MEN This page intentionally left blank Napoleon's Men The Soldiers of the Revolution and Empire Alan Forrest hambledon continuum Hambledon Continuum The Tower Building 11 York Road London, SE1 7NX 80 Maiden Lane Suite 704 New York, NY 10038 First Published 2002 in hardback This edition published 2006 ISBN 1 85285 269 0 (hardback) ISBN 1 85285 530 4 (paperback) Copyright © Alan Forrest 2002 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyrights reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book. A description of this book is available from the British Library and the Library of Congress. Typeset by Carnegie Publishing, Lancaster, and printed in Great Britain by MPG Books, Cornwall. Contents Illustrations vii Introduction ix Acknowledgements xvii 1 The Armies of the Revolution and Empire 1 2 The Soldiers and their Writings 21 3 Official Representation of War 53 4 The Voice of Patriotism 79 5 From Valmy to Moscow 105 6 Everyday Life in the Armies 133 7 The Lure of Family and Farm 161 8 From One War to Another 185 Notes 205 Bibliography 227 Index 241 This page intentionally left blank Illustrations Between pages 108 and 109 1 Napoleon Bonaparte, crossing the Alps in 1800 2 Volunteers enrolling 3 Protesting -

The Beaumont Hamel Newfoundland Memorial on the Somme, Cultural Geographies, 11, Pp.235-258

[email protected] Gough, P.J. (2004) Sites in the imagination: the Beaumont Hamel Newfoundland Memorial on the Somme, Cultural Geographies, 11, pp.235-258 Sites in the imagination: the Beaumont Hamel Newfoundland Memorial on the Somme. Professor Paul Gough University of the West of England, Bristol Frenchay Bristol BS16 [email protected] ABSTRACT The Beaumont Hamel Newfoundland Memorial is a 16.5 hectare (40 acres) tract of preserved battleground dedicated to the memory of the 1st Newfoundland Regiment who suffered an extremely high percentage of casualties during the first day of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916. Beaumont Hamel Memorial is an extremely complex landscape 1 [email protected] of commemoration where Newfoundland, Canadian, Scottish and British imperial associations compete for prominence. It is argued in the paper that those who chose the site of the Park, and subsequently re-ordered its topography, helped to contrive a particular historical narrative that prioritised certain memories over others. In its design, the park has been arranged to indicate the causal relationship between distant military command and immediate front-line response, and its topographical layout focuses exclusively on a thirty-minute military action during a fifty-month war. In its preserved state the part played by the Royal Newfoundland Regiment can be measured, walked and vicariously experienced. Such an achievement has required close semiotic control and territorial demarcation in order to render the „invisible past‟ visible, and to convert an emptied landscape into significant reconstructed space. This paper examines the initial preparation of the site in the 1920s and more recent periods of conservation and reconstruction. -

Newfoundland's Cultural Memory of the Attack at Beaumont Hamel

Glorious Tragedy: Newfoundland’s Cultural Memory of the Attack at Beaumont Hamel, 1916-1925 ROBERT J. HARDING THE FIRST OF JULY is a day of dual significance for Newfoundlanders. As Canada Day, it is a celebration of the dominion’s birth and development since 1867. In Newfoundland and Labrador, the day is also commemorated as the anniversary of the Newfoundland Regiment’s costliest engagement during World War I. For those who observe it, Memorial Day is a sombre occasion which recalls this war as a trag- edy for Newfoundland, symbolized by the Regiment’s slaughter at Beaumont Hamel, France, on 1 July 1916. The attack at Beaumont Hamel was depicted differently in the years immedi- ately following the war. Newfoundland was then a dominion, Canada was an impe- rial sister, and politicians, clergymen, and newspaper editors offered Newfoundlanders a cultural memory of the conflict that was built upon a trium- phant image of Beaumont Hamel. Newfoundland’s war myth exhibited selectively romantic tendencies similar to those first noted by Paul Fussell in The Great War and Modern Memory.1 Jonathan Vance has since observed that Canadians also de- veloped a cultural memory which “gave short shrift to the failures and disappoint- ments of the war.”2 Numerous scholars have identified cultural memory as a dynamic social mechanism used by a society to remember an experience common to all its members, and to aid that society in defining and justifying itself.3 Beau- mont Hamel served as such a mechanism between 1916 and 1925. By constructing a triumphant memory based upon selectivity, optimism, and conjured romanticism, local mythmakers hoped to offer grieving and bereaved Newfoundlanders an in- spiring and noble message which rationalized their losses. -

Reveille – November 2020

Reveille – November 2020 Reveille – No.3 November 2020 The magazine of Preston & Central Lancashire WFA southribble-greatwar.com 1 Reveille – November 2020 In Flanders fields the poppies blow Between the crosses, row on row, That mark our place; and in the sky The larks, still bravely singing, fly Scarce heard amid the guns below. We are the Dead. Short days ago We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, Loved and were loved, and now we lie, In Flanders fields. Take up our quarrel with the foe: To you from failing hands we throw The torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die We shall not sleep, though poppies grow In Flanders fields. John McCrae Cover photograph by Charlie O’Donnell Oliver at the Menin Gate 2 Reveille – November 2020 Welcome… …to the November 2020 edition of our magazine Reveille. The last few months have been difficult ones for all of us particularly since we are not able to meet nor go on our usual travels to the continent. In response the WFA has been hosting a number of online seminars and talks – details of all talks to the end of the year and how they can be accessed are reproduced within this edition. The main theme of this edition is remembrance. We have included articles on various War Memorials in the district and two new ones this branch has had a hand in creating. The branch officers all hope that you are well and staying safe. We wish you all the best for the holiday season and we hope to meet you again in the new year. -

Rushmoor Men Who Died During the Battle of the Somme

Rushmoor men who died during the Battle of the Somme Compiled by Paul H Vickers, Friends of the Aldershot Military Museum, January 2016 Introduction To be included in this list a man must be included in the Rushmoor Roll of Honour: citizens of Aldershot, Farnborough and Cove who fell in the First World War as a resident of Rushmoor at the time of the First World War. The criteria for determining residency and the sources used for each man are detailed in the Rushmoor Roll of Honour. From the Rushmoor Roll of Honour men were identified who had died during the dates of the battle of the Somme, 1 July to 18 November 1916. Men who died up to 30 November were also considered to allow for those who may have died later of wounds received during the battle. To determine if they died at the Somme, consideration was then given to their unit and the known locations and actions of that unit, whether the man was buried in one of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) Somme cemeteries or listed on a memorial to the missing of the Somme, mainly the Thiepval Memorial, or who are noted in the Roll of Honour details as having died at the Somme or as a result of wounds sustained at the Somme. The entries in this list are arranged by regiment and battalion (or battery for the Royal Artillery). For each man the entry from the Rushmoor Roll of Honour is given, and for each regiment or battalion there is a summary of its movements up to the start of the Battle of the Somme and its participation in the battle up to the time the men listed were killed. -

National World War I Memorial Presentation for Final Approval

U.S. COMMISSION OF FINE ARTS SUBMISSION | SEPTEMBER 19, 2019 National World War I Memorial Presentation for Final Approval Sculptor SABIN HOWARD 1 PRESENTATION CONTENT SUMMARY OF PREVIOUS / UPCOMING PRESENTATIONS • Concept Lighting, Furnishing and Finishes (February 2019) • Response to Walkway, Lighting, and Sculpture Fountain Comments (April 2019) • Interpretation and Detailing (May 2019) • Response to Sculpture and Lighting Comments + Site Security and Final Detailing (July 2019) • Design Recap for Final Approval (anticipated September 2019) PRESENTATION OBJECTIVES (9/19/2019) • Final Approval PRESENTATION OUTLINE • Project Scope and Background • Existing Conditions • Design Summary - Organizing Framework - Balancing Two Works of Art - Memorial Park Design - Memorial Park Program - Interpretive Framework • 1st Tier Commemorative Features - Existing Pershing Memorial - A Soldier’s Journey - Peace Fountain - Sculpture Fountain • 2nd Tier Commemorative Features - Belvedere - Tactile Model - Inscriptions - Flagstaff • 3rd Tier Commemorative Features - Information Poppies • Supporting Elements - Viewing Platform - ADA Accessibility Improvements - Park History Wayside - Lighting - Entry Signage and Site Security Measures - Acknowledgments Panel • Planting - Existing Canopy - Proposed Canopy - Understory 2 PROJECT SCOPE AND BACKGROUND 3 PROJECT SCOPE AND BACKGROUND INTRODUCTION Of the four major wars of the twentieth century, World War I alone has no national memorial in the nation’s capital. More American servicemen were lost in World War I than in the Korean and Vietnam wars combined, with 116,516 lost and 200,000 more wounded. In December 2014, President Obama signed legislation authorizing the U.S. World War I Centennial Commission (WWICC) to establish a new memorial. P.L.113- 291, Section 3091 of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2015 re-designates Pershing Park in the District of Columbia, an existing memorial to General John J.