April 15—17, 2016 Benedum Center for the Performing Arts 1 Audience Production Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon Du Diable

Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable Edited and Introduced by Robert Ignatius Letellier Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable, Edited by Edited and Introducted by Robert Ignatius Letellier This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Edited and Introducted by Robert Ignatius Letellier and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3608-7, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3608-1 Cesare Pugni in London (c. 1845) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................... ix Esmeralda Italian Version La corte del miracoli (Introduzione) .......................................................................................... 2 Allegro giusto............................................................................................................................. 5 Sposalizio di Esmeralda ............................................................................................................. 6 Allegro giusto............................................................................................................................ -

CALL for PAPERS MLADA-MSHA International Network CLARE-ARTES Research Center (Bordeaux) Organize an International Symposium Оn

CALL FOR PAPERS MLADA-MSHA International Network CLARE-ARTES Research Center (Bordeaux) Organize an international symposium оn 21-22-23 October, 2015 At Bordeaux Grand Theatre FROM BORDEAUX TO SAINT PETERSBURG, MARIUS PETIPA (1818-1910) AND THE « RUSSIAN » BALLET The great academic ballet, known as « Russian ballet », is the product of a historical process initiated in 18th century in Russia and completed in the second part of 19th century by Victor-Marius-Alphonse Petipa (1818-1910), principal ballet master of the Saint Petersburg Imperial Theatres from 1869 to his death. Born in Marseilles in a family of dancers and actors, Marius Petipa, after short- term contracts in several theatres, including Bordeaux Grand Theatre, pursued a more than 50 years long carreer in Russia, when he became « Marius Ivanovitch ». He layed down the rules of the great academic ballet and left for posterity over 60 creations, among which the most famous are still presented on stages all around the world. Petipa’s name has become a synonym of classical ballet. His work has been denigrated, parodied, or reinterpreted ; however, its meaning remains central in the reflection of contemporary choreographers, as we can see from young South African choreographer Dada Masilo’s recent new version of Swan Lake. Moreover, Petipa’s work still fosters controversies as evidenced by the reconstructions of his ballets by S.G. Vikharev at the Mariinsky theatre or Teatro alla Scala, and by Iu. P. Burlaka at the Bolchoï. Given the world-famous name of Petitpa one might expect his œuvre, as a common set of fundamental values for international choreographic culture, to be widely known. -

Scaramouche and the Commedia Dell'arte

Scaramouche Sibelius’s horror story Eija Kurki © Finnish National Opera and Ballet archives / Tenhovaara Scaramouche. Ballet in 3 scenes; libr. Paul [!] Knudsen; mus. Sibelius; ch. Emilie Walbom. Prod. 12 May 1922, Royal Dan. B., CopenhaGen. The b. tells of a demonic fiddler who seduces an aristocratic lady; afterwards she sees no alternative to killinG him, but she is so haunted by his melody that she dances herself to death. Sibelius composed this, his only b. score, in 1913. Later versions by Lemanis in Riga (1936), R. HiGhtower for de Cuevas B. (1951), and Irja Koskkinen [!] in Helsinki (1955). This is the description of Sibelius’s Scaramouche, Op. 71, in The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Ballet. Initially, however, Sibelius’s Scaramouche was not a ballet but a pantomime. It was completed in 1913, to a Danish text of the same name by Poul Knudsen, with the subtitle ‘Tragic Pantomime’. The title of the work refers to Italian theatre, to the commedia dell’arte Scaramuccia character. Although the title of the work is Scaramouche, its main character is the female dancing role Blondelaine. After Scaramouche was completed, it was then more or less forgotten until it was published five years later, whereupon plans for a performance were constantly being made until it was eventually premièred in 1922. Performances of Scaramouche have 1 attracted little attention, and also Sibelius’s music has remained unknown. It did not become more widely known until the 1990s, when the first full-length recording of this remarkable composition – lasting more than an hour – appeared. Previous research There is very little previous research on Sibelius’s Scaramouche. -

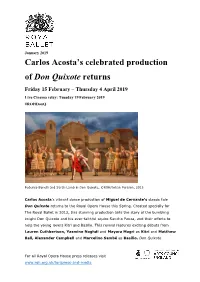

Don Quixote Press Release 2019

January 2019 Carlos Acosta’s celebrated production of Don Quixote returns Friday 15 February – Thursday 4 April 2019 Live Cinema relay: Tuesday 19 February 2019 #ROHDonQ Federico Bonelli and Sarah Lamb in Don Quixote, ©ROH/Johan Persson, 2013 Carlos Acosta’s vibrant dance production of Miguel de Cervante’s classic tale Don Quixote returns to the Royal Opera House this Spring. Created specially for The Royal Ballet in 2013, this stunning production tells the story of the bumbling knight Don Quixote and his ever-faithful squire Sancho Panza, and their efforts to help the young lovers Kitri and Basilio. This revival features exciting debuts from Lauren Cuthbertson, Yasmine Naghdi and Mayara Magri as Kitri and Matthew Ball, Alexander Campbell and Marcelino Sambé as Basilio. Don Quixote For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media includes a number of spectacular solos and pas de deux as well as outlandish comedy and romance as the dashing Basilio steals the heart of the beautiful Kitri. Don Quixote will be live streamed to cinemas on Tuesday 19 February as part of the ROH Live Cinema Season. Carlos Acosta previously danced the role of Basilio in many productions of Don Quixote. He was invited by Kevin O’Hare Director of The Royal Ballet, to re-stage this much-loved classic in 2013. Acosta’s vibrant production evokes sunny Spain with designs by Tim Hatley who has also created productions for the National Theatre and for musicals including Dreamgirls, The Bodyguard and Shrek. Acosta’s choreography draws on Marius Petipa’s 1869 production of this classic ballet and is set to an exuberant score by Ludwig Minkus arranged and orchestrated by Martin Yates. -

Spring Performances Celebrate Class of 2018

Fall 2018 Spring Performances Celebrate Class of 2018 The Morris and Elfriede Stonzek Spring Performances, presented last May, served as a fitting celebration of the 2018 graduating class and a wonderful way to kick off Memorial Day weekend. In keeping with tradition, the performances opened with a presentation of the fifteen seniors who would receive their diplomas the following week—HARID’s largest-ever graduating class. Alex Srb photo © Srb photo Alex The program opened with The Fairy Doll Pas de Trois, staged by Svetlana Osiyeva and Meelis Pakri. Catherine Alex Srb © Alex Doherty sparkled as the fairy doll, in an exquisite pink tutu, while David Rathbun and Jaysan Stinnett (cast as the two A scene from the Black Swan Pas de Deux, Swan Lake, Act III pierrots competing for her attention) accomplished the challenging technical elements of the ballet while endearingly portraying their comedic characters. The next work on the program was the premiere of It Goes Without Saying, choreographed for HARID by resident choreographer Mark Godden. Set to music by Nico Muhly and rehearsed by Alexey Kulpin, this work stretched the artistic scope of the dancers by requiring them to speak on stage and move in unison to music that is not always melodically driven. The ballet featured a haunting pas de Alex Srb photo © Srb photo Alex deux, performed maturely by Anna Gonzalez and Alexis Alex Srb © Alex Valdes, and a spirited, playful duet for dancers Tiffany Chatfield and Chloe Crenshaw. The Fairy Doll Pas de Trois The second half of the program featured Excerpts from Swan Lake, Acts I and III. -

SWAN LAKE Dear Educators in the Winter Show of Oregon Ballet Theatre’S Student Performance Series (SPS) Students Will Be Treated to an Excerpt from Swan Lake

STUDENT PERFORMANCE SERIES STUDY GUIDE / Feburary 21, 2013 / Keller Auditorium / Noon - 1:00 pm, doors open at 11:30am SWAN LAKE Dear Educators In the winter show of Oregon Ballet Theatre’s Student Performance Series (SPS) students will be treated to an excerpt from Swan Lake. It is a quintessential ballet based on a heart-wrenching fable of true love heroically won and tragically Photo by Joni Kabana by Photo squandered. With virtuoso solos and an achingly beautiful score, it is emblematic of the opulent grandeur of the greatest of all 19th-Century story ballets. This study guide is designed to help teachers prepare students for their trip to the theatre where they will see Swan Lake Act III. In this Study Guide we will: • Provide the entire synopsis for Christopher Stowell’sSwan Lake, consider some of the stories that inspired the ballet, Principal Dancer Yuka Iino and Guest Artist Ruben Martin in Christopher and touch on its history Stowell’s Swan Lake. Photo by Blaine Truitt Covert. • Look closely at Act III • Learn some facts about the music for Swan Lake • Consider the way great dances are passed on to future generations and compare that to how students come to know other great works of art or literature • Describe some ballet vocabulary, steps and choreographic elements seen in Swan Lake • Include internet links to articles and video that will enhance learning At the theatre: • While seating takes place, the audience will enjoy a “behind the scenes” look at the scenic transformation of the stage • Oregon Ballet Theatre will perform Act III from Christopher Stowell’s Swan Lake where Odile’s evil double tricks the Prince into breaking his vow of love for the Swan Queen. -

QCF Examinations Information, Rules & Regulations

Specifications for qualifications regulated in England, Wales and Northern Ireland incorporating information, rules and regulations about examinations, class awards, solo performance awards, presentation classes and demonstration classes This document is valid from 1 July 2018 1 The Royal Academy of Dance (RAD) is an international teacher education and awarding organisation for dance. Established in 1920 as the Association of Operatic Dancing of Great Britain, it was granted a Royal Charter in 1936 and renamed the Royal Academy of Dancing. In 1999 it became the Royal Academy of Dance. Vision Leading the world in dance education and training, the Royal Academy of Dance is recognised internationally for the highest standards of teaching and learning. As the professional membership body for dance teachers it inspires and empowers dance teachers and students, members, and staff to make innovative, artistic and lasting contributions to dance and dance education throughout the world. Mission To promote and enhance knowledge, understanding and practice of dance internationally by educating and training teachers and students and by providing examinations to reward achievement, so preserving the rich, artistic and educational value of dance for future generations. We will: communicate openly collaborate within and beyond the organisation act with integrity and professionalism deliver quality and excellence celebrate diversity and work inclusively act as advocates for dance. Examinations Department Royal Academy of Dance 36 Battersea Square London SW11 3RA Tel +44 (0)20 7326 8000 [email protected] www.rad/org.uk/examinations © Royal Academy of Dance 2017 ROYAL ACADEMY OF DANCE, RAD, and SILVER SWANS are registered trademarks® of the Royal Academy of Dance in a number of jurisdictions. -

Men's Glee Repertoire (2002-2021)

MEN'S GLEE REPERTOIRE (2002-2021) Ain-a That Good News - William Dawson All Ye Saints Be Joyful - Katherine Davis Alleluia - Ralph Manuel Ave Maria - Franz Biebl Ave Maria - Jacob Arcadet Ave Maria - Joan Szymko Ave Maris Stella - arr. Dianne Loomer Beati Mortui - Fexlix Mendelssohn Behold the Lord High Executioner (from The Mikado )- Gilbert and Sullivan Blades of Grass and Pure White Stones -Orin Hatch, Lowell Alexander, Phil Nash/ arr. Keith Christopher Blagoslovi, dushé moyá Ghospoda - Mikhail Mikhailovich Ippolitov-Ivanov Blow Ye Trumpet - Kirke Mechem Bright Morning Stars - Shawn Kirchner Briviba – Ēriks Ešenvalds Brothers Sing On - arr. Howard McKinney Brothers Sing On - Edward Grieg Caledonian Air - arr. James Mullholland Come Sing to Me of Heaven - arr. Aaron McDermid Cornerstone – Shawn Kirchner Coronation Scene (from Boris Goudonov ) - Modest Petrovich Moussorgsky Creator Alme Siderum - Richard Burchard Daemon Irrepit Callidu- György Orbain Der Herr Segne Euch (from Wedding Cantata ) - J. S. Bach Dereva ni Mungu – Jake Runestad Dies Irae - Z. Randall Stroope Dies Irae - Ryan Main Do You Hear the Wind? - Leland B. Sateren Do You Hear What I Hear? - arr. Harry Simeone Down in the Valley - George Mead Duh Tvoy blagi - Pavel Chesnokov Entrance and March of the Peers (from Iolanthe)- Gilbert and Sullivan Five Hebrew Love Songs - Eric Whitacre For Unto Us a Child Is Born (from Messiah) - George Frideric Handel Gaudete - Michael Endlehart Git on Boa'd - arr. Damon H. Dandridge Glory Manger - arr. Jon Washburn Go Down Moses - arr. Moses Hogan God Who Gave Us Life (from Testament of Freedom) - Randall Thompson Hakuna Mungu - Kenyan Folk Song- arr. William McKee Hark! I Hear the Harp Eternal - Craig Carnahan He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands - arr. -

Historie a Vývoj Baletní Scény Mariinského Divadla

Univerzita Hradec Králové Pedagogická fakulta Katedra ruského jazyka a literatury Historie a vývoj baletní scény Mariinského divadla Diplomová práce Autor: Bc. Andrea Plecháčová Studijní program: N7504 – Učitelství pro střední školy Studijní obor: Učitelství pro střední školy – základy společenských věd Učitelství pro střední školy – ruský jazyk a literatura Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jaroslav Sommer Oponent práce: prof. PhDr. Ivo Pospíšil, DrSc. Hradec Králové 2020 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracovala (pod vedením vedoucího diplomové práce) samostatně a uvedla jsem všechny použité prameny a literaturu. V Hradci Králové dne … ………………………… Bc. Andrea Plecháčová Poděkování Ráda bych poděkovala svému vedoucímu panu Mgr. Jaroslavu Sommerovi za odborné vedení a cenné rady při vypracovávání diplomové práce. Dále děkuji paní Mgr. Jarmile Havlové za pomoc při korektuře gramatické stránky práce. Anotace PLECHÁČOVÁ, Andrea. Historie a vývoj baletní scény Mariinského divadla. Hradec Králové: Pedagogická fakulta Univerzity Hradec Králové, 2020. 66 s. Diplomová práce. Práce se zaměřuje na historii a vývoj baletní scény Mariinského divadla po současnost. Věnuje se také nejslavnějším osobnostem a inscenacím baletní scény Mariinského divadla v Petrohradě. Klíčová slova: balet, divadlo, Petrohrad, umění, Leningrad, Kirovovo divadlo opery a baletu, Mariinské divadlo. Annotation PLECHÁČOVÁ, Andrea. History and Development of the Mariinsky Ballet. Hradec Králové: Faculty of Education, University of Hradec Králové, 2020. 66 pp. Diploma Dissertation Degree Thesis. The thesis focuses on the history and development of the ballet stage of the Mariinsky Theatre up to the present. It is also dedicated to the most outstanding personalities and stagings of the Mariinsky Theatre in Petersburg. Keywords: ballet, theatre, Saint Petersburg, art, Leningrad, Kirov Theatre, The Mariinsky Theatre. -

Ballet Notes Giselle

Ballet Notes Giselle May 27 – 31, 2009 Chan Hon Goh as Giselle. Photo by David Cooper. 2008/09 Orchestra Violins Clarinets • Fujiko Imajishi, • Max Christie, Principal Souvenir Book Concertmaster Emily Marlow, Lynn Kuo, Acting Principal Acting Concertmaster Gary Kidd, Bass Clarinet On Sale Now in the Lobby Dominique Laplante, Bassoons Principal Second Violin Stephen Mosher, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., Founder James Aylesworth, Jerry Robinson Featuring beautiful new images Acting Assistant Elizabeth Gowen, George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Concertmaster by Canadian photographer Contra Bassoon Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Jennie Baccante Sian Richards Artistic Director Executive Director Sheldon Grabke Horns Xiao Grabke Gary Pattison, Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Nancy Kershaw Vincent Barbee Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-Leheniuk Derek Conrod Principal Conductor • Csaba Koczó • Scott Wevers Yakov Lerner Trumpets Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Jayne Maddison Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Richard Sandals, Principal Ron Mah YOU dance / Ballet Master Mark Dharmaratnam Aya Miyagawa Raymond Tizzard Aleksandar Antonijevic, Guillaume Côté, Wendy Rogers Chan Hon Goh, Greta Hodgkinson, Filip Tomov Trombones Nehemiah Kish, Zdenek Konvalina, Joanna Zabrowarna David Archer, Principal Heather Ogden, Sonia Rodriguez, Paul Zevenhuizen Robert Ferguson David Pell, Piotr Stanczyk, Xiao Nan Yu Violas Bass Trombone Angela Rudden, Principal Victoria Bertram, Kevin D. Bowles, Theresa Rudolph Koczó, Tuba -

JUNE 3-13 Baumgartner Center for Dance on Demand Milwaukeeballet.Org

JUNE 3-13 Baumgartner Center for Dance On Demand milwaukeeballet.org THE 2020-21 SEASON IS SPONSORED BY DONNA & DONALD BAUMGARTNER Lahna Vanderbush. Photo Timothy O’Donnell This program was supported in part by a grant from Wisconsin Arts Board with funds from the State of Wisconsin and the National Endowment for the Arts. LETTER FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear friends, Welcome to Encore, which we proudly present in our lovely home, Baumgartner Center for Dance. I’ve curated cherished works from our archives to celebrate all we have accomplished together this season, despite the challenges. Thank you for joining our celebration. The classical variations in this program span the most beloved scenes in the ballet world: Don Quixote, Raymonda, Giselle. You will also enjoy excerpts from both a luminary and a rising star in contemporary dance: Trey McIntyre returns with A Day in the Life and Aleix Mañé shares his ExiliO, which won our international Genesis competition. In this program, we also celebrate our friend Jimmy Gamonet, who passed earlier this year from COVID-19. Jimmy is most notable for his longtime tenure as Miami City Ballet’s founding resident choreographer and ballet master. He staged three of his works here, the most well-known being Nous Sommes, which we warmly present as an affectionate tribute to his memory. On behalf of the entire organization, I would like to thank our season sponsors, Donna and Donald Baumgartner, as well as United Performing Arts Fund, for their unwavering support. We will announce our upcoming season in only a few short weeks and hope you will join us at Marcus Performing Arts Center this fall. -

Gainesville Ballet Contact

Gainesville Ballet Contact: Elysabeth Muscat 7528 Old Linton Hall Road [email protected] Gainesville, VA 20155 703-753-5005 www.gainesvilleballetcompany.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 1, 2015 ABT BALLET STARS BOYLSTON AND WHITESIDE IN GAINESVILLE BALLET NUTCRACKER GAINESVILLE, Va. – Gainesville Ballet is excited to announce two performances of The Nutcracker on Friday, November 27, 2015 at 2 PM and 7 PM. The full-length ballet features ballet superstars, international guest dancers, the professional dancers of Gainesville Ballet Company, and the students of Gainesville Ballet School. What better way to continue the celebration of the Thanksgiving holiday weekend, than to see a beautiful, professional performance of The Nutcracker at the elegant opera house of the 1,123-seat Merchant Hall at the Hylton Performing Arts Center! Audiences who reside in Northern Virginia and beyond will have the rare opportunity to see two of American Ballet Theatre’s most exciting Principal Dancers, Isabella Boylston and James Whiteside. James Whiteside and Isabella Boylston in Giselle. Isabella Boylston was promoted to Principal Dancer at American Ballet Photo by MIRA. Theatre in 2014. She originally joined ABT as part of the Studio Company in 2005, joined the main company as an apprentice in 2006, and became a member of the corps de ballet in 2007. She was promoted to Soloist in 2011, before recently becoming Principal. Boylston began dancing at the age of three at The Boulder Ballet. At age 12, she joined the Academy of Colorado Ballet in Denver, Colorado, where she commuted two hours on a public bus to study there each day.