Michele Boldrin David K Levine [20110408] What's Intellectual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shopping Externalities and Self-Fulfilling Unemployment Fluctuations

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES SHOPPING EXTERNALITIES AND SELF-FULFILLING UNEMPLOYMENT FLUCTUATIONS Greg Kaplan Guido Menzio Working Paper 18777 http://www.nber.org/papers/w18777 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 February 2013 We thank the Kielts-Nielsen Data Center at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business for providing access to the Kielts-Nielsen Consumer Panel Dataset. We thank the editor, Harald Uhlig, and three anonymous referees for insightful and detailed suggestions that helped us revising the paper. We are also grateful to Mark Aguiar, Jim Albrecht, Michele Boldrin, Russ Cooper, Ben Eden, Chris Edmond, Roger Farmer, Veronica Guerrieri, Bob Hall, Erik Hurst, Martin Schneider, Venky Venkateswaran, Susan Vroman, Steve Williamson and Randy Wright for many useful comments. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2013 by Greg Kaplan and Guido Menzio. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Shopping Externalities and Self-Fulfilling Unemployment Fluctuations Greg Kaplan and Guido Menzio NBER Working Paper No. 18777 February 2013, Revised October 2013 JEL No. D11,D21,D43,E32 ABSTRACT We propose a novel theory of self-fulfilling unemployment fluctuations. According to this theory, a firm hiring an additional worker creates positive external effects on other firms, as a worker has more income to spend and less time to search for low prices when he is employed than when he is unemployed. -

Economics 2009 Contents Highlights

Economics 2009 www.cambridge.org/economics Contents Highlights Economic Thought, Philosophy and Methodology 1 Econometrics 2 Econometric Society Monographs 3 Mathematical Methods and Pro- gramming 3 Microeconomics 4 Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics 5 International Economics 6 ➤ See page 22 World Trade Organization 8 ➤ See page 22 Finance and Financial Economics 10 ➤ See page 02 Public Economics and Political Economy 13 A Wealth of Knowledge and Learning… Institutional Economics 18 Industrial Organisation and Labour Economics 19 ...Economics Journals from Cambridge Business and Management 20 Economic History 22 1744-1374_4-1.qxd.goldlabel 15/1/08 09:46 Page 1 14747472_6-3.qxd.1stproof 26/10/07 11:59 Page 1 Economic Growth and Development 22 02662671_23-3.qxd.goldlabel.qxd 2/11/07 08:41 Page 1 81.7/')&+557''(&&.È+550'&*(#--', Journal of Institutional Economics volume 6 issue 3 november 2007 volume 6 issue 3 november 2007 THE JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF ECONOMIC THOUGHT ISSN 1744-1374 THE JOURNAL OF THE Journal of Volume 23 Number 3 November 2007 Economics Economics 22 Journal of HISTORY OF Institutional Journal of Journal of Economics Economics Pension Economics Journal of & Finance Pension Economics & F &Philosophy Environmental and Natural Re- Volume 23 Number 3 November 2007 ECONOMIC THOUGHT vol 4 • no 1 • APRIL 2008 Institutional & Economics ➤ See page 22 Pension Economics Phi 81.7/')&+557'' Articles articles Franz Dietrich and Strategy-Proof Judgment Aggregation 269 los source Economics 24 ➤ PMS 109 233 A model of the French pension reserve fund: what could be the optimal See page 10 Christian List &Philosophy THE JOURNAL OF THE Economics contribution path rate? ophy Igor Douven and The Discursive Dilemma as a Lottery Paradox 301 PMS Yellow 012 Yellow PMS Charlie Berger and Anne Lavigne & Finance Jan-Willem Romeijn Contents PMS 329 251 Behavioral effects of employer-sponsored retirement plans: evidence from Watson ◆ MARSHALL’S METAPHORS ON METHOD PP. -

Michele Boldrin Spring 2017 a Primer on Growth Theory

Michele Boldrin Spring 2017 A Primer on Growth Theory Scope The purpose of this course is to introduce you to some of the basic dynamic general equilibrium concepts and models I believe useful to start understanding economic growth and macroeconomic fluctuations. No representative agent with log utility and a Cobb-Douglas production function will be found in this class, you have already seen them. Apart from discussing extensively the little we know, and the lot we do not know, about the empirics of economic growth and business cycles, we will make an effort to understand how to model heterogeneous agents and a disaggregated (or complicated if you like) production structure. Organizational details We will meet six times, for three hours each (with a break in the middle …). We will dedicate each meeting to a specific topic or issue. The first half of the meeting will be dedicated to “teaching the topic” and the second half to “discussing the topic”. I presume you will do some reading before each meeting and I will assign you specific suggestions as the time comes. There are no assigned textbooks, but a number of reference texts are listed below. I will be mailing you additional reading materials week by week, depending on how fast we proceed. Grading I will give you a take-home exam at the end of the course. Topics 1. Growth and Cycles, data and historical facts. The theory of growth and the theory of cycles. Understanding the aggregate neoclassical growth model and the origin of the so-called “new growth theory”. -

Micro-Modeling of Retirement Behavior in Spain

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Social Security Programs and Retirement around the World: Micro-Estimation Volume Author/Editor: Jonathan Gruber and David A. Wise, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-31018-3 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/grub04-1 Publication Date: January 2004 Title: Micro-Modeling of Retirement Behavior in Spain Author: Michele Boldrin, Sergi Jiménez-Martín, Franco Peracchi URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10707 9 Micro-Modeling of Retirement Behavior in Spain Michele Boldrin, Sergi Jiménez-Martín, and Franco Peracchi 9.1 Introduction For the average Spaniard receiving a pension still means receiving a public pension. Among retired individuals, those drawing more than 10 percent of their annual income from a private pension plan are a negligible fraction (less than one percent). The situation, while slowly evolving, will not change substantially for another two decades or more. In 1990, the to- tal number of participants in all kinds of private pension plans was of 600,000—less than 5 percent of total employment at the time. Since then, participation in pension funds has increased rapidly but not exceptionally, reaching a total of 4 million at the end of 1999. This is slightly less than 30 percent of current total employment and is mostly composed of individu- als that are at relatively early stages of their working life. It is therefore rea- sonable to expect that, at least for the next two to three decades, the public pension system will remain the fundamental provider of old age income for Spanish citizens. -

Curriculum Vitae Et Studiorum – May 2019 –

Curriculum vitae et studiorum { May 2019 { Pietro Dindo Department of Economics, Ca' Foscari University of Venice Cannaregio 873, 30121 - Venice, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Web-page: http://virgo.unive.it/pietro.dindo/ PERSONAL INFORMATION Date of Birth: 21st December 1976 Place of Birth: Verona (Italy) Nationality: Italian Status: Married Children: Nicola (2007), Tommaso (2009), Federico (2015) ACADEMIC AND RESEARCH POSITIONS February 2016 - Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Ca' Foscari University of Venice. August 2013 - January 2016 Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellow, Department of Economics, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY and Institute of Economics, Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies, Pisa January 2012 - July 2013 Assistant Professor, Department of Economics and Management, University of Pisa. September 2009 - December 2011 Assistant Professor, Institute of Economics, Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies, Pisa. December 2006 - August 2009 Post-Doctoral Researcher, Institute of Economics, Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies, Pisa. EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS September 2002 - January 2007 PhD in Economics - Tinbergen Institute and University of Amsterdam. Thesis title: Bounded Rationality and Heterogeneity in Economic Dynamic Models (supervised by Cars Hommes and Cees Diks) September 2002 - June 2004 MPhil in Economics - Tinbergen Institute and University of Amsterdam. Thesis title: An Evolutionary Approach to the El Farol Game. October 1995 - October 2000 MSc in Physics - University of Milan. Thesis title: Renormalization Group for a Scalar Field on a Lattice (in Italian). PUBLICATIONS Dindo, P. (2019). \Survival in speculative markets". Journal of Economic Theory, 181, 1{43. Dindo, P., J. Staccioli (2018). \Asset prices and wealth dynamics in a financial market with random demand shocks". -

RAUL SANTAEULALIA-LLOPIS July 30, 2021 Education Current Position(S) Previous Positions Work in Progress

RAUL SANTAEULALIA-LLOPIS July 30, 2021 Department of Economics Place of Birth : Algemes´ı (Valencia), Spain Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona Citizenship : Spanish Plac¸a Civica s/n, Bellaterra, Barcelona 08193, Spain Telephone : 93 581 2708 E-mail : rauls[at]movebarcelona.eu Homepage : http://r-santaeulalia.net Education Ph.D. in Economics, University of Pennsylvania 2008 Thesis Advisor: Prof. Jose-V´ ´ıctor R´ıos-Rull M.Sc. in Economics, University College London 2002 B.A. in Economics, Universitat de Valencia 2000 Current position(s) Beatriz Galindo Senior Researcher, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona Sep 2019 - Affilated Research Professor, Barcelona Graduate School of Economics Sep 2016 - CEPR Research Fellow Sep 2020 - MOVE Research Fellow Sep 2016 - Previous Positions Associate Professor (with tenure), Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona (UAB) Sep 2018 - 2019 Visiting Scholar OIGI, Minneapolis FED Apr 2018 - 2019 Vice-Director, Markets Organizations and Votes in Economics (MOVE) Jan 2017 - 2019 Assistant Professor, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona (UAB) Sep 2016 - 2018 Visiting Professor, CEMFI Sep 2015 - 2016 Visiting Professor, Universitat de Valencia Sep 2013 - 2016 Research Fellow, St. Louis FED Sep 2010 - 2016 Research Fellow, Insitute of Public Health, Washington University in St. Louis Sep 2010 - 2016 Assistant Professor, Washington University in St. Louis Sep 2008 - 2016 Work in Progress 5. ‘Progressivity and Development’, with Leandro de Magalhaes and Enric Martorell 4. ‘Resilient Kaldor: Growth Facts with Intellectual Property Products Capital’, with S. Aum and D. Koh First Draft available as Barcelona GSE Working Paper: 1029 3. ‘A Stage-Based Identification of Policy Effects’, with Christian Aleman, Chris Busch and Alex Ludwig First Draft available as Barcelona GSE Working Paper: 1209 2. -

What Happened to the US Stock Market?

What Happened to the U.S. Stock Market? Accounting for the Past 50 Years Michele Boldrin and Adrian Peralta-Alva The extreme volatility of stock market values has been the subject of a large body of literature. Previous research focused on the short run because of a widespread belief that in the long run the market reverts to well-established fundamentals. The authors’ research suggests this belief should be questioned. First, they show actual dividends cannot account for the secular trends of stock market values. They then consider a more comprehensive measure of capital income, which displays large secular fluctuations that roughly coincide with changes in stock market trends. Under perfect foresight, however, this measure fails to proper ly account for stock market movements. The authors thus abandon the perfect foresight assumption and instead assume that forecasts of future capital income are performed using a distributed lag equation and information available up to the forecasting period only. They find that standard asset-pricing theory can be reconciled with the secular trends in the stock market. This study, nevertheless, leaves open an important puzzle for asset-pricing theory: The market value of U.S. corporations was much lower than the replacement cost of corporate tangible assets from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s. (JEL E25, G12) Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, November/December 2009, 91(6), pp. 627-46. tandard (consumption-based) asset- gyrations by appropriately filtering the quarterly pricing models have a hard time explain- movements of aggregate consumption is unlikely ing high-frequency fluctuations in stock to be realized. -

Classical Liberalism in Italian Economic Thought, from the Time of Unification · Econ Journal Watch : Italy,Classical Liberalis

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: http://journaltalk.net/articles/5933 ECON JOURNAL WATCH 14(1) January 2017: 22–54 Classical Liberalism in Italian Economic Thought, from the Time of Unification Alberto Mingardi1 LINK TO ABSTRACT This paper offers an account of Italians who have advanced liberal ideas and sensibilities, with an emphasis on individual freedom in the marketplace, since the time of Italy’s unification. We should be mindful that Italy has always had a vein of liberal thought. But this gold mine of liberalism was seldom accessed by political actors, and since 1860 liberalism has been but one thin trace in Italy’s mostly illiberal political thought and culture. The leading representatives of Italian liberalism since 1860 are little known internationally, with the exception of Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923). And yet their work influenced the late James M. Buchanan and the development of public choice economics.2 Scholars such as Bruno Leoni (1913–1967) joined—and influenced— liberals around the world, and they continue to have an impact on Italy today. Besides their scholarship, all the liberal authors mentioned here share a constant willingness to enter the public debate.3 Viewed retrospectively they appear a pugnacious lot, even if not highly successful in influencing public policy. The standout is Luigi Einaudi (1874–1961), at once a scholar and journalist who also became a leading political figure in the period after World War II. 1. Istituto Bruno Leoni, 10123 Turin, Italy. I am grateful to Jane Shaw Stroup for valuable editorial feed- back. I also wish to thank Enrico Colombatto and three anonymous referees for their helpful comments. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87928-6 - Against Intellectual Monopoly Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine Frontmatter More information AGAINST INTELLECTUAL MONOPOLY “Intellectual property” – patents and copyrights – has become controversial. We witness teenagers being sued for “pirating” music, and we observe AIDS patients in Africa dying because of their lack of ability to pay for drugs that are expensively priced by patent holders. Are patents and copyrights essential to thriving creation and innovation? Do we need them so that we all may enjoy fine music and good health? Across time and space the resounding answer is: No. So-called intellectual property is in fact an “intellectual monopoly” that hinders rather than helps the competitive free market regime that has delivered wealth and innovation to our doorsteps. This book broadly covers both copyrights and patents and is designed for a general audience, with its focus on everyday examples. The authors conclude that the only sensible policy to follow is to eliminate the patent and copyright systems as they currently exist. Michele Boldrin is Joseph G. Hoyt Distinguished Professor of Economics in Arts and Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. He is a Fellow of the Econometric Society and a Research Fellow at the Center for Economic Pol- icy Research (London) and at Fundacion´ de Estudios de Econom´ıa Aplicada (Madrid). He is an associate editor of Econometrica, an editor of Review of Economic Dynamics, and an advisory editor of Macroeconomic Dynamics,pub- lished by Cambridge University Press. His research interests include growth, innovation, and business cycles; intergenerational and demographic issues; public policy; institutions; and social norms. -

Michele Boldrin Spring 2018 a Prime on Money and Growth

Michele Boldrin Spring 2018 A Prime on Money and Growth Scope The purpose of this course is to introduce you to the current state of research on two topics: the theory of economic growth and the theory of money. The course is mostly theoretical but there will be abundant references to facts, data and historical evidence. Organization of the course We will meet eight times, for three hours each (first class will be shorter, 1.5 hours). We will dedicate each meeting to a specific topic or issue. I assume you will do quite a bit of reading before each meeting and I will assign you specific suggestions about what to read (the reading list below is a starting point but it contains mostly classical papers). I like to organize the class as follows: I teach an argument in the second 1.5 hours of lecture n, for n=1,2, …7 and assign some reading to the class. In the first 1.5 hours of lecture n+1 you illustrate and discuss the content of the assigned readings and I try to put them in the proper perspective. This works well as the lecture n=1 is only 1.5 hours, hence I will discuss what we know about economic growth from data and history. I will use the last half of lecture n=8 to wrap up the course and take some final questions. It is therefore ESSENTIAL that you read and make an effort to understand the assigned materials. Grading I will give you a take-home exam at the end of the course. -

Lee Edward Ohanian

Lee Edward Ohanian August 2020 UCLA, Department of Economics Work: (310) 825-0979 405 Hilgard Avenue Cell: (310) 968-6008 Los Angeles, CA 90095 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.leeohanian.com Fields of Specialization Macroeconomics, International Economics. Education Ph.D. Economics University of Rochester, 1993 M.A. Economics University of Rochester, 1992 B.A. Economics U.C. Santa Barbara, 1979, with high honors Primary Faculty Appointments 2000 – Present , Professor of Economics, UCLA. (Vice Chair 2000-2004, 2006). 1999 – 2000, Associate Professor of Economics, UCLA. 1995 – 1999, Assistant and Associate Professor of Economics, University of Minnesota. 1992 – 1995, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. Research and Visiting Appointments 2011 – Present, Senior Fellow, Hoover Institution, Stanford University 2011, Sam B. Cook Visiting Professor of Economics (Inaugural Chair Holder), Washington University, St. Louis 2010 – Present, Associate Director, Center for the Advanced Study in Economic Efficiency, Arizona State University 2010, John Weatherall Distinguished Fellow, Department of Economics, Queen’s University -1- 2009, Cowles Foundation Fellow, Department of Economics, Yale University 2007 - Present, Co-Director, (with Jeremy Greenwood), NBER Working Group “Macroeconomics Across Time and Space” 2003 – Present, Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research Industry Experience 1982 - 88 Vice President and Economist, Security Pacific National Bank, Los Angeles, CA 1981 - 82 Senior Research Analyst, Continental Airlines, Los Angeles, CA. Public Policy Consulting 1993 – Present Consultant to various Federal Reserve banks and international central banks in other countries Honors, Fellowships, and Prizes 2001 - 2017 Scoville Distinguished Teaching Prize, UCLA 2012 – Present Fellow, Society for the Advancement of Economic Theory 1994 - 1996 Lawrence R. -

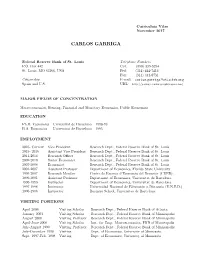

Carlos Garriga

Curriculum Vitae November 2017 CARLOS GARRIGA Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Telephone Numbers P.O. Box 442 Cell: (850) 339-5254 St. Louis, MO 63166, USA Fed: (314) 444-7412 Fax: (314) 444-8731 Citizenship E-mail: [email protected] Spain and U.S. URL: http://garriga.carlos.googlepages.com/ MAJOR FIELDS OF CONCENTRATION Macroeconomics, Housing, Financial and Monetary Economics, Public Economics EDUCATION Ph.D. Economics Universitat de Barcelona 1996-99 B.A. Economics Universitat de Barcelona 1995 EMPLOYMENT 2016- Current Vice President Research Dept., Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 2015- 2016 Assistant Vice President Research Dept., Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 2011-2014 Research Offi cer Research Dept., Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 2009-2010 Senior Economist Research Dept., Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 2007-2008 Economist Research Dept., Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 2001-2007 Assistant Professor Department of Economics, Florida State University 1999-2007 Research Member Centre de Recerca d’Economiadel Benestar (CREB) 1999-2001 Assistant Professor Department of Economics, Universitat de Barcelona 1996-1999 Instructor Department of Economics, Universitat de Barcelona 1997-1998 Instructor Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (U.N.E.D.) 1996-1998 Instructor Business School, Universitat de Barcelona VISITING POSITIONS April 2006 Visiting Scholar Research Dept., Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta January 2001 Visiting Scholar Research Dept., Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis August 2000 Visiting Professor Research Dept., Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis April-June 2000 Visiting Scholar Inst. for Emp. Macroeconomics, FRB of Minneapolis July-August 1999 Visiting Professor Research Dept., Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis July-December 1998 Visiting Dept.