MBI 2019 Kakkonen Etal.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Warrants Received: May 2021

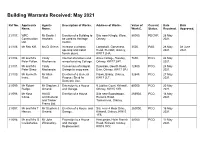

Building Warrants Received: May 2021 Ref No. Applicants Agents Description of Works. Address of Works. Value of Current Date Date Name. Name. Work £. Status. Received. Approved. 21/107. WRC Mr Bashir I Erection of a Building to Site near Kringlo, Wyre, 85000. RECNP. 28 May Construction Hasham. be used as Heritage Orkney. 2021. Ltd. Centre. 21/106. Mr Rob Kiff. Ms Di Grieve. Increase a window Langskaill, Gorseness 3500. PAS. 28 May 08 June opening and install Road, Rendall, Orkney, 2021. 2021. french doors. KW17 2HA. 21/104. Mr and Mrs Cindy Internal alterations and Alma Cottage, Sanday, 7600. PCO. 24 May Peter Fallon. Mackenzie. re-roof existing Cottage. Orkney, KW17 2AY. 2021. 21/101. Mr and Mrs Cindy Conversion of integral Dykeside, Georth Road, 12500. PCO. 24 May Peter Shaw. Mackenzie. Garage to snug area. Evie, Orkney, KW17 2PJ. 2021. 21/100. Mr Kenneth Mr Allan Erection of a General Flaws, Birsay, Orkney, 32848. PCO. 27 May Irvine. Reid. Purpose Shed for KW17 2LT. 2021. Domestic Use. 21/099. Mr Robert Mr Stephen J Extension to a House 9 Jubilee Court, Kirkwall, 80000. PCO. 20 May Budge. Omand. and Garage. Orkney, KW15 1XR. 2021. 21/098. Mr Ross HAUS Erection of a House. Site near Boondatoon, 266902. PCO. 18 May Corse. Architectural Rerwick Road, 2021. and Timber Tankerness, Orkney. Frame Ltd. 21/097. Mr and Mrs T Mr Stephen J Erection of a House and Site near 4 Moar Drive, 260000. PCO. 18 May Harcus. Omand. Garage. Kirkwall, Orkney, KW15 2021. 1FS. 21/096. Mr and Mrs G Mr John Extension to a House Hescombe, Holm Branch 30000. -

Ferry Timetables

1768 Appendix 1. www.orkneyferries.co.uk GRAEMSAY AND HOY (MOANESS) EFFECTIVE FROM 24 SEPTEMBER 2018 UNTIL 4 MAY 2019 Our service from Stromness to Hoy/Graemsay is a PASSENGER ONLY service. Vehicles can be carried by prior arrangement to Graemsay on the advertised cargo sailings. Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Stromness dep 0745 0745 0745 0745 0745 0930 0930 Hoy (Moaness) dep 0810 0810 0810 0810 0810 1000 1000 Graemsay dep 0825 0825 0825 0825 0825 1015 1015 Stromness dep 1000 1000 1000 1000 1000 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1030 1030 1030 1030 1030 Graemsay dep 1045 1045 1045 1045 1045 Stromness dep 1200A 1200A 1200A Graemsay dep 1230A 1230A 1230A Hoy (Moaness) dep 1240A 1240A 1240A Stromness dep 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 Graemsay dep 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 Stromness dep 1745 1745 1745 1745 1745 Graemsay dep 1800 1800 1800 1800 1800 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1815 1815 1815 1815 1815 Stromness dep 2130 Graemsay dep 2145 Hoy (Moaness) dep 2200 A Cargo Sailings will have limitations on passenger numbers therefore booking is advisable. These sailings may be delayed due to cargo operations. Notes: 1. All enquires must be made through the Kirkwall Office. Telephone: 01856 872044. 2. Passengers are requested to be available for boarding 5 minutes before departure. 3. Monday cargo to be booked by 1600hrs on previous Friday otherwise all cargo must be booked before 1600hrs the day before sailing. Cargo must be delivered to Stromness Pier no later than 1100hrs on the day of sailing. -

Genetic Control of Diurnal and Lunar Emergence Times Is Correlated in the Marine Midge Clunio Marinus Tobias S Kaiser1,2*, Dietrich Neumann3 and David G Heckel1

Kaiser et al. BMC Genetics 2011, 12:49 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2156/12/49 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Timing the tides: Genetic control of diurnal and lunar emergence times is correlated in the marine midge Clunio marinus Tobias S Kaiser1,2*, Dietrich Neumann3 and David G Heckel1 Abstract Background: The intertidal zone of seacoasts, being affected by the superimposed tidal, diurnal and lunar cycles, is temporally the most complex environment on earth. Many marine organisms exhibit lunar rhythms in reproductive behaviour and some show experimental evidence of endogenous control by a circalunar clock, the molecular and genetic basis of which is unexplored. We examined the genetic control of lunar and diurnal rhythmicity in the marine midge Clunio marinus (Chironomidae, Diptera), a species for which the correct timing of adult emergence is critical in natural populations. Results: We crossed two strains of Clunio marinus that differ in the timing of the diurnal and lunar rhythms of emergence. The phenotype distribution of the segregating backcross progeny indicates polygenic control of the lunar emergence rhythm. Diurnal timing of emergence is also under genetic control, and is influenced by two unlinked genes with major effects. Furthermore, the lunar and diurnal timing of emergence is correlated in the backcross generation. We show that both the lunar emergence time and its correlation to the diurnal emergence time are adaptive for the species in its natural environment. Conclusions: The correlation implies that the unlinked genes affecting lunar timing and the two unlinked genes affecting diurnal timing could be the same, providing an unexpectedly close interaction of the two clocks. -

Belgian Register of Marine Species

BELGIAN REGISTER OF MARINE SPECIES September 2010 Belgian Register of Marine Species – September 2010 BELGIAN REGISTER OF MARINE SPECIES, COMPILED AND VALIDATED BY THE VLIZ BELGIAN MARINE SPECIES CONSORTIUM VLIZ SPECIAL PUBLICATION 46 SUGGESTED CITATION Leen Vandepitte, Wim Decock & Jan Mees (eds) (2010). Belgian Register of Marine Species, compiled and validated by the VLIZ Belgian Marine Species Consortium. VLIZ Special Publication, 46. Vlaams Instituut voor de Zee (VLIZ): Oostende, Belgium. 78 pp. ISBN 978‐90‐812900‐8‐1. CONTACT INFORMATION Flanders Marine Institute – VLIZ InnovOcean site Wandelaarkaai 7 8400 Oostende Belgium Phone: ++32‐(0)59‐34 21 30 Fax: ++32‐(0)59‐34 21 31 E‐mail: [email protected] or [email protected] ‐ 2 ‐ Belgian Register of Marine Species – September 2010 Content Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... ‐ 5 ‐ Used terminology and definitions ....................................................................................................... ‐ 7 ‐ Belgian Register of Marine Species in numbers .................................................................................. ‐ 9 ‐ Belgian Register of Marine Species ................................................................................................... ‐ 12 ‐ BACTERIA ............................................................................................................................................. ‐ 12 ‐ PROTOZOA ........................................................................................................................................... -

The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 5 Print Reference: Pages 561-572 Article 43 2003 The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island Lawson L. Schroeder Philip L. Schroeder Bryan College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Schroeder, Lawson L. and Schroeder, Philip L. (2003) "The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 5 , Article 43. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol5/iss1/43 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ANCIENT STANDING STONES, VILLAGES AND TOMBS FOUND ON THE ORKNEY ISLANDS LAWSON L. SCHROEDER, D.D.S. PHILIP L. SCHROEDER 5889 MILLSTONE RUN BRYAN COLLEGE STONE MOUNTAIN, GA 30087 P. O. BOX 7484 DAYTON, TN 37321-7000 KEYWORDS: Orkney Islands, ancient stone structures, Skara Brae, Maes Howe, broch, Ring of Brodgar, Standing Stones of Stenness, dispersion, Babel, famine, Ice Age ABSTRACT The Orkney Islands make up an archipelago north of Scotland. -

De Novo Draft Assembly of the Botrylloides Leachii Genome

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/152983; this version posted June 21, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 De novo draft assembly of the Botrylloides leachii genome 2 provides further insight into tunicate evolution. 3 4 Simon Blanchoud1#, Kim Rutherford2, Lisa Zondag1, Neil Gemmell2 and Megan J Wilson1* 5 6 1 Developmental Biology and Genomics Laboratory 7 2 8 Department of Anatomy, School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Otago, P.O. Box 56, 9 Dunedin 9054, New Zealand 10 # Current address: Department of Zoology, University of Fribourg, Switzerland 11 12 * Corresponding author: 13 Email: [email protected] 14 Ph. +64 3 4704695 15 Fax: +64 479 7254 16 17 Keywords: chordate, regeneration, Botrylloides leachii, ascidian, tunicate, genome, evolution 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/152983; this version posted June 21, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 18 Abstract (250 words) 19 Tunicates are marine invertebrates that compose the closest phylogenetic group to the 20 vertebrates. This chordate subphylum contains a particularly diverse range of reproductive 21 methods, regenerative abilities and life-history strategies. Consequently, tunicates provide an 22 extraordinary perspective into the emergence and diversity of chordate traits. Currently 23 published tunicate genomes include three Phlebobranchiae, one Thaliacean, one Larvacean 24 and one Stolidobranchian. To gain further insights into the evolution of the tunicate phylum, 25 we have sequenced the genome of the colonial Stolidobranchian Botrylloides leachii. -

Assessing the Impact of Key Marine Invasive Non-Native Species on Welsh MPA Habitat Features, Fisheries and Aquaculture

Assessing the impact of key Marine Invasive Non-Native Species on Welsh MPA habitat features, fisheries and aquaculture. Tillin, H.M., Kessel, C., Sewell, J., Wood, C.A. Bishop, J.D.D Marine Biological Association of the UK Report No. 454 Date www.naturalresourceswales.gov.uk About Natural Resources Wales Natural Resources Wales’ purpose is to pursue sustainable management of natural resources. This means looking after air, land, water, wildlife, plants and soil to improve Wales’ well-being, and provide a better future for everyone. Evidence at Natural Resources Wales Natural Resources Wales is an evidence based organisation. We seek to ensure that our strategy, decisions, operations and advice to Welsh Government and others are underpinned by sound and quality-assured evidence. We recognise that it is critically important to have a good understanding of our changing environment. We will realise this vision by: Maintaining and developing the technical specialist skills of our staff; Securing our data and information; Having a well resourced proactive programme of evidence work; Continuing to review and add to our evidence to ensure it is fit for the challenges facing us; and Communicating our evidence in an open and transparent way. This Evidence Report series serves as a record of work carried out or commissioned by Natural Resources Wales. It also helps us to share and promote use of our evidence by others and develop future collaborations. However, the views and recommendations presented in this report are not necessarily those of -

Festive Period Domestic and Commercial Refuse Collections

Festive Period Domestic and Commercial Refuse Collections Mainland and Linked South Isles Domestic and commercial refuse collection days over the Christmas and New Year period are listed below. Regular waste collections will resume on Monday 6 January 2020. Domestic and Fortnightly Trade Refuse Collections Area. Normally Collected. Refuse Collection Dates. Area 1 – Kirkwall (Central and North West). Monday. Monday 23 December. Area 3 – Kirkwall (Central). Wednesday. Monday 23 December. Area 6 – East Holm, Deerness, Tankerness and Toab. Monday. Monday 23 December. Area 2 – Kirkwall (West). Tuesday. Tuesday 24 December. Area 7 – Kirkwall (South), Holm, Burray (North). Tuesday. Tuesday 24 December. Area 8 – South Ronaldsay and Burray (South). Wednesday. Tuesday 24 December. Area 4 – Kirkwall (South East). Thursday. Friday 27 December. Area 5 – Kirkwall (North East). Friday. Friday 27 December. Area 9 – Stromness (Central). Monday. Monday 30 December. Area 11 –Stromness (Outer), Sandwick and Birsay. Wednesday. Monday 30 December. Area 10 – Stromness (Outer Areas) and Stenness (West). Tuesday. Tuesday 31 December. Area 12 – Dounby, Birsay and Evie. Thursday. Friday 3 January 2020. Area 13 – Firth, Rendall, Evie and Harray. Friday. Friday 3 January 2020. Area 14 – Finstown, Stenness (East) and Harray. Thursday. Friday 3 January 2020. Area. Normally Collected. Refuse Collection Dates. Area 15 – Orphir and Stenness (West). Friday. Friday 3 January 2020. Domestic Recycling Information Please note alterations for domestic recycling collection over the festive period. Recycling centres will remain open – see separate advert for opening times. Area: Last recycling collection: Next recycling collection: Area 1 – Kirkwall (Central and North West). Monday 16 December. Monday 13 January 2020. Area 6 – East Holm, Deerness, Tankerness and Toab. -

Species Are Hypotheses: Avoid Connectivity Assessments Based on Pillars of Sand Eric Pante, Nicolas Puillandre, Amélia Viricel, Sophie Arnaud-Haond, D

Species are hypotheses: avoid connectivity assessments based on pillars of sand Eric Pante, Nicolas Puillandre, Amélia Viricel, Sophie Arnaud-Haond, D. Aurelle, Magalie Castelin, Anne Chenuil, Christophe Destombe, Didier Forcioli, Myriam Valero, et al. To cite this version: Eric Pante, Nicolas Puillandre, Amélia Viricel, Sophie Arnaud-Haond, D. Aurelle, et al.. Species are hypotheses: avoid connectivity assessments based on pillars of sand. Molecular Ecology, Wiley, 2015, 24 (3), pp.525-544. hal-02002440 HAL Id: hal-02002440 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02002440 Submitted on 31 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Molecular Ecology Species are hypotheses : avoid basing connectivity assessments on pillars of sand. Journal:For Molecular Review Ecology Only Manuscript ID: Draft Manuscript Type: Invited Reviews and Syntheses Date Submitted by the Author: n/a Complete List of Authors: Pante, Eric; UMR 7266 CNRS - Université de La Rochelle, Puillandre, Nicolas; MNHN, Systematique & Evolution Viricel, Amélia; UMR 7266 CNRS - -

Wreck of the Edindoune (BF1118), Scapa Flow, Orkney. Final Report

Wreck of the Edindoune (BF1118), Scapa Flow, Orkney. Final Report Submitted to: Historic Environment Scotland - Philip Robertson Contact: Kevin Heath SULA Diving Old Academy Stromness Orkney KW16 3AW Tel. 01856 850 285 E-mail. [email protected] Approved for release by M. Thomson (Director): Document history Version: State Prepared by: Date: 02 Final M. Thomson/K. Heath 26th March 2018 01 Draft M. Thomson/K. Heath 22nd March 2018 CONTENTS PAGE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………………………………………. ii SUMMARY………………......................................................................................................... iii 1. INTRODUCTION……………................................................................................................ 1 2. METHODS....................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Side scan sonar………………………………………………………………………………………………... 2 2.2 Diving……………………………………………………………………………………………….……………... 2 3. RESULTS.......................................................................................................................... 3 3.1 Side scan sonar...................................................................................................... 3 3.2 Diving………………….................................................................................................. 3 4. DISCUSSION.................................................................................................................... 17 REFERENCES & BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................... -

First Record of the Marine Alien Amphipod Caprella Mutica (Schurin, 1935) in South Africa

BioInvasions Records (2017) Volume 6, Issue 1: 61–66 Open Access DOI: https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2017.6.1.10 © 2017 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2017 REABIC Rapid Communication First record of the marine alien amphipod Caprella mutica (Schurin, 1935) in South Africa Koebraa Peters and Tamara B. Robinson* Centre for Invasion Biology, Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Matieland, 7602, South Africa E-mail addresses: [email protected] (KP), [email protected] (TBR) *Corresponding author Received: 22 July 2016 / Accepted: 5 December 2016 / Published online: 15 December 2016 Handling editor: Elisabeth Cook Abstract We report the first discovery of the marine amphipod Caprella mutica (Schurin, 1935), commonly known as the Japanese skeleton shrimp, in South African waters. This amphipod is indigenous to north-east Asia and has invaded several regions, including Europe, North America, New Zealand and now South Africa. C. mutica was detected in scrape samples from the hulls and niche areas of four yachts resident to False Bay Marina, Simon’s Town, on South Africa’s South Coast. A total of 2,157 individuals were recorded, comprising 512 males, 966 females (20% of which were gravid) and 679 juveniles. The yachts upon which this amphipod was found were not alongside each other, suggesting that the species is widely distributed within the marina. The presence of C. mutica in South Africa has been anticipated, as previous work highlighted the climatic suitability of the region and the presence of vectors between South Africa and other invaded areas. The fast reproductive cycle of C. mutica, along with its high reproductive output, have important implications for its invasiveness in South Africa. -

Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Regeneration in Colonial and Solitary MARK Ascidians ⁎ Susannah H

Developmental Biology 448 (2019) 271–278 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Developmental Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/developmentalbiology Review article Cellular and molecular mechanisms of regeneration in colonial and solitary MARK Ascidians ⁎ Susannah H. Kassmer , Shane Nourizadeh, Anthony W. De Tomaso Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, USA ABSTRACT Regenerative ability is highly variable among the metazoans. While many invertebrate organisms are capable of complete regeneration of entire bodies and organs, whole-organ regeneration is limited to very few species in the vertebrate lineages. Tunicates, which are invertebrate chordates and the closest extant relatives of the vertebrates, show robust regenerative ability. Colonial ascidians of the family of the Styelidae, such as several species of Botrylloides, are able to regenerate entire new bodies from nothing but fragments of vasculature, and they are the only chordates that are capable of whole body regeneration. The cell types and signaling pathways involved in whole body regeneration are not well understood, but some evidence suggests that blood borne cells may play a role. Solitary ascidians such as Ciona can regenerate the oral siphon and their central nervous system, and stem cells located in the branchial sac are required for this regeneration. Here, we summarize the cellular and molecular mechanisms of tunicate regeneration that have been identified so far and discuss differences and similarities