Hera, the Sphinx?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Journal Intime D'hercule D'andré Dubois La Chartre. Typologie Et Réception Contemporaine Du Mythe D'hercule

Commission de Programme en langues et lettres françaises et romanes Le Journal intime d’Hercule d’André Dubois La Chartre. Typologie et réception contemporaine du mythe d’Hercule Alice GILSOUL Mémoire présenté pour l’obtention du grade de Master en langues et lettres françaises et romanes, sous la direction de Mme. Erica DURANTE et de M. Paul-Augustin DEPROOST Louvain-la-Neuve Juin 2017 2 Le Journal intime d’Hercule d’André Dubois La Chartre. Typologie et réception contemporaine du mythe d’Hercule 3 « Les mythes […] attendent que nous les incarnions. Qu’un seul homme au monde réponde à leur appel, Et ils nous offrent leur sève intacte » (Albert Camus, L’Eté). 4 Remerciements Je tiens à remercier Madame la Professeure Erica Durante et Monsieur le Professeur Paul-Augustin Deproost d’avoir accepté de diriger ce travail. Je remercie Madame Erica Durante qui, par son écoute, son exigence, ses précieux conseils et ses remarques m’a accompagnée et guidée tout au long de l’élaboration de ce présent mémoire. Mais je me dois surtout de la remercier pour la grande disponibilité dont elle a fait preuve lors de la rédaction de ce travail, prête à m’aiguiller et à m’écouter entre deux taxis à New-York. Je remercie également Monsieur Paul-Augustin Deproost pour ses conseils pertinents et ses suggestions qui ont aidé à l’amélioration de ce travail. Je le remercie aussi pour les premières adresses bibliographiques qu’il m’a fournies et qui ont servi d’amorce à ma recherche. Mes remerciements s’adressent également à mes anciens professeurs, Monsieur Yves Marchal et Madame Marie-Christine Rombaux, pour leurs relectures minutieuses et leurs corrections orthographiques. -

Thomas Hart Benton MS Text

Thomas Hart Benton: Painter of Everyday America Thomas Hart Benton was born in Missouri in 1889. Throughout his long life he made thousands of drawings and paintings. He was inspired by his experiences of America. As a boy his mother took Tom, his two sisters, and his brother to visit her family in Texas. He traveled with his father, who was running for US Congress. When his father won, the Bentons lived in Washington DC. They came home to Missouri in the summers, where young Tom had a pony, took care of a cow, and picked strawberries. Thomas Hart Benton, 1925, Self Portrait, oil on canvas Collection of the artist;‘s daughter, Jessie Benton Lyman. (It was on the cover of Time magazine, December 24, 1934 Tom's first job was as a newspaper artist in Joplin, Missouri. He studied art in Chicago, Illinois, then in Paris, and finally in New York, New York. During World War I, Benton served in the Navy in Norfolk, Virginia. He created camouflage paint designs for Navy ships. After the war, Benton returned to New York City where he taught art. There he met and married his wife, Rita. The Benton family lived most of the year in New York, and spent their summers on an island off Thomas Hart Benton, 1943, July Hay, egg tempera and oil on the coast of masonite, 38” x 26.7/8” Massachusetts. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York The death of his father was a shock to Benton. He started to take long walks in the Catskill Mountains of New York. -

Hercules Abstracts

Hercules: A hero for all ages Hover the mouse over the panel title, hold the Ctrl key and right click to jump to the panel. 1a) Hercules and the Christians ................................... 1 1b) The Tragic Hero ..................................................... 3 2a) Late Mediaeval Florence and Beyond .................... 5 2b) The Comic Hero ..................................................... 7 3a) The Victorian Age ................................................... 8 3b) Modern Popular Culture ....................................... 10 4a) Herculean Emblems ............................................. 11 4b) Hercules at the Crossroads .................................. 12 5a) Hercules in France ............................................... 13 5b) A Hero for Children? ............................................ 15 6a) C18th Political Imagery ......................................... 17 6b) C19th-C21st Literature ........................................... 19 7) Vice or Virtue (plenary panel) ............................... 20 8) Antipodean Hercules (plenary panel) ................... 22 1a) Hercules and the Christians Arlene Allan (University of Otago) Apprehending Christ through Herakles: “Christ-curious” Greeks and Revelation 5-6 Primarily (but not exclusively) in the first half of the twentieth century, scholarly interest has focussed on the possible influence of the mythology of Herakles and the allegorizing of his trials amongst philosophers (especially the Stoics) on the shaping of the Gospel narratives of Jesus. This -

Bulfinch's Mythology

Bulfinch's Mythology Thomas Bulfinch Bulfinch's Mythology Table of Contents Bulfinch's Mythology..........................................................................................................................................1 Thomas Bulfinch......................................................................................................................................1 PUBLISHERS' PREFACE......................................................................................................................3 AUTHOR'S PREFACE...........................................................................................................................4 STORIES OF GODS AND HEROES..................................................................................................................7 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................7 CHAPTER II. PROMETHEUS AND PANDORA...............................................................................13 CHAPTER III. APOLLO AND DAPHNEPYRAMUS AND THISBE CEPHALUS AND PROCRIS7 CHAPTER IV. JUNO AND HER RIVALS, IO AND CALLISTODIANA AND ACTAEONLATONA2 AND THE RUSTICS CHAPTER V. PHAETON.....................................................................................................................27 CHAPTER VI. MIDASBAUCIS AND PHILEMON........................................................................31 CHAPTER VII. PROSERPINEGLAUCUS AND SCYLLA............................................................34 -

Hercules: a Hero for All Ages

Hercules: A hero for all ages Hover the mouse over the panel title, hold the Ctrl key and right click to jump to the panel. 1a) Hercules and the Christians ................................... 1 1b) The Tragic Hero ..................................................... 3 2a) Late Mediaeval Florence and Beyond .................... 6 2b) The Comic Hero ..................................................... 7 3a) The Victorian Age ................................................... 8 3b) Modern Popular Culture ......................................... 9 4a) Herculean Emblems ............................................. 11 4b) Renaissance Literature ........................................ 13 5a) Hercules in France ............................................... 14 5b) A Hero for Children? ............................................ 16 6a) C18th Political Imagery ......................................... 18 6b) C19th-C21st Literature ........................................... 19 7a) Opera ................................................................... 21 7b) Vice or Virtue ........................................................ 22 8) Antipodean Hercules (plenary panel) ................... 24 1a) Hercules and the Christians Arlene Allan (University of Otago) Apprehending Christ through Herakles: “Christ-curious” Greeks and Revelation 5-6 Primarily (but not exclusively) in the first half of the twentieth century, scholarly interest has focussed on the possible influence of the mythology of Herakles and the allegorizing of his trials amongst -

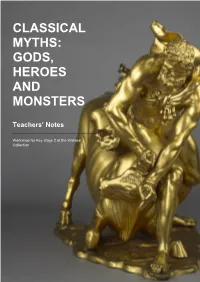

Classical Myths: Gods, Heroes and Monsters

CLASSICAL MYTHS: GODS, HEROES AND MONSTERS Teachers’ Notes Workshop for Key stage 2 at the Wallace Collection Classical Myths Teachers’ Notes Workshop for Key stage 2 at the Wallace Collection. Come face-to-face with Hercules, Perseus and Classical Myths at the Wallace Collection Apollo, characters from ancient Greek and Roman myths whose stories are told in paintings, Homer’s phrase, ‘winged words’, reaches us from the sculptures, furniture and ceramics. Find out how sixth century B.C. With his own winged words, these stories have inspired artists through the ages Homer wrote many of the great myths and legends of and finish with some observational drawing. This the classical world and, after a visit to the Wallace workshop is aimed at key stage 2 and lasts an hour Collection, students will be inspired not only to and a half. research and explore ways of interpreting them but to write their own. Stories by Homer, Virgil and others from the pre-Christian era were re-discovered centuries later, when Greek and Roman sculptures of gods, goddesses, heroes and heroines were being unearthed and their myths passed down to a new and excited audience in the 16th and 17th centuries A.D. They remain the greatest stories ever told and are the basis of most stories made today. Many of the paintings and sculptures in the Wallace Collection were created during this time and are among the greatest of its treasures. They bring the stories to life in a specific way – portraying drama through movement and emotion captured in paint, bronze and marble, gold and enamel, exciting the viewer and showing off the artist’s prowess in the painting of characters, animals, fabrics, landscape backgrounds and in the nudes that were typical of classical times. -

Ovid's Metamorphoses

OVID’S METAMORPHOSES Continuum Reader’s Guides Continuum’s Reader’s Guides are clear, concise and accessible introductions to classic works. Each book explores the major themes, historical and philosophical context and key passages of a major classical text, guiding the reader toward a thorough understanding of often demanding material. Ideal for undergraduate students, the guides provide an essential resource for anyone who needs to get to grips with a classical text. Reader’s Guides available from Continuum Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics – Christopher Warne Aristotle’s Politics – Judith A. Swanson and C. David Corbin Plato’s Republic – Luke Purshouse Plato’s Symposium – Thomas L. Cooksey OVID’S METAMORPHOSES A Reader’s Guide GENEVIEVE LIVELEY Continuum International Publishing Group The Tower Building 80 Maiden Lane 11 York Road Suite 704 London SE1 7NX New York, NY 10038 www.continuumbooks.com © Genevieve Liveley, 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-1-4411-2519-4 PB: 978-1-4411-0084-9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Liveley, Genevieve. Ovid’s Metamorphoses : a reader’s guide / Genevieve Liveley. p. cm. – (Reader’s guides) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4411-0084-9 (pbk.) – ISBN 978-1-4411-2519-4 (hardback) 1. Ovid, 43 B.C.–17 or 18 A.D. -

Bibliographie Zum Nachleben Des Antiken Mythos

Bibliographie zum Nachleben des antiken Mythos von Bernhard Kreuz, Petra Aigner & Christine Harrauer Version vom 26.07.2012 Wien, 2012 Inhaltsverzeichnis I. Allgemeine Hilfsmittel .............................................................................................................. 3 I.1. Hilfsmittel zum 16.–18. Jhd. .............................................................................................. 3 I.1.1. Lexika zur Rennaissance .............................................................................................. 3 I.1.2. Biographische Lexika ................................................................................................... 3 I.1.3. Bibliographische Hilfsmittel ........................................................................................ 4 I.1.4. Neulateinische Literatur im Internet ............................................................................ 4 I.2. Moderne Lexika zur Mythologie (in Auswahl) ................................................................. 4 I.2.1. Grundlegende Lexika zur antiken Mythologie und Bildersprache .............................. 4 I.2.2. Lexika zur antiken Mythologie und ihrem Nachleben ................................................. 5 Spezialwerke zur bildenden Kunst ......................................................................................... 5 Spezialwerke zur Musik ......................................................................................................... 6 I.2.3. Zu mythologischen Nachschlagewerken der -

Bulfinch's Mythology the Age of Fable by Thomas Bulfinch

1 BULFINCH'S MYTHOLOGY THE AGE OF FABLE BY THOMAS BULFINCH Table of Contents PUBLISHERS' PREFACE ........................................................................................................................... 3 AUTHOR'S PREFACE ................................................................................................................................. 4 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 7 ROMAN DIVINITIES ............................................................................................................................ 16 PROMETHEUS AND PANDORA ............................................................................................................ 18 APOLLO AND DAPHNE--PYRAMUS AND THISBE CEPHALUS AND PROCRIS ............................ 24 JUNO AND HER RIVALS, IO AND CALLISTO--DIANA AND ACTAEON--LATONA AND THE RUSTICS .................................................................................................................................................... 32 PHAETON .................................................................................................................................................. 41 MIDAS--BAUCIS AND PHILEMON ....................................................................................................... 48 PROSERPINE--GLAUCUS AND SCYLLA ............................................................................................. 53 PYGMALION--DRYOPE-VENUS -

Meanings and Second Meanings

Achelous and Hercules (detail), 1947, Thomas Hart Benton, 62 7/8 x 264 1/8 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of Allied Stores Corporation, and museum purchase through the Smithso- nian Institution Collections Acquisition Program Meanings and Second Meanings Symbolism appears in both art and writing. Simile and your friend eats sloppily. Everyone knows that a person metaphor appear only in writing. All of these devices are is not really a farm animal. ways to convey meaning. If you write a story about a pig that could also be under- A simile compares one thing to another. (A simile usually stood as a story about your friend—you have written a has the word like or as in it.) symbolic story. The pig stands for your friend. Those who know your friend might recognize him or her, even with A metaphor calls one thing by the name of something else— floppy ears and a curly tail. Others might simply enjoy something that is similar to the first thing in some way. your story as the adventures of a pig. For example: In a story like that, the reader is meant to discover the If you say to your friend, “You eat like a pig!” you’re using second meaning. A good example is Animal Farm by a simile. George Orwell. On one level it is a story about animals on a farm. But it is also a story of life under an oppres- If you say to him or her, “You’re a real pig!” you’re using sive government. -

Greece and Rome

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 1 – Europe: South: Greece and Rome Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 1 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. -

The Characteristics of Myth Through Hercules and Achelous Battle

The characteristics of myth through Hercules and Achelous battle Trying to give a definition to myth we can say that it is a fictional, made up narration often with symbolic or figurative elements. Generally we can say that a myth which contains fictional or actual facts is trying to interpret the creation of the world, to show how the world was made and at the same time the forces that ruins it. Concerning the reasons why humans create myths are numerous. One basic reason is the need to give answers to the questions that bothered him feeling weak in front of nature’s greatness, not able to explain the natural phenomena and logically explain forces and facts that influenced his life. Thus during the period that human was still in the prelogical state of his culture, myth was the only way to express and give answers to the questions that bothered him. Also human used myths in order to remember the things he saw, lived or imagined. It is a fact that myths were the fundamental elements in both Ancient and Modern Greek culture, so even today we can notice the values and attitudes of the period in question such as love, nature, beauty, the greatness of the human soul and values. Myths according to content and ideas are distinguished in various categories. The first ones are those which are trying to interpret the creation of the world and gods. Those are called Theogonic or Cosmogenic. There are myths that are trying to interpret the creation and origin of the human kind, the Anthropogonic myths.