Television History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRIDGING MEDIA-SPECIFIC APPROACHES the Value of Feminist Television Criticism’S Synthetic Approach

BRIDGING MEDIA-SPECIFIC APPROACHES The value of feminist television criticism’s synthetic approach Amanda D. Lotz and Sharon Marie Ross Introduction Feminist study of media encompasses a variety of media forms, each of which possesses a distinct set of issues determined by the medium and how it is used, as well as by the variant theoretical and methodological traditions through which scholars have studied the medium. US feminist film and television criticism have maintained distinct methodological and theoretical emphases—yet the two areas of study are closely related. For example, feminist television studies developed from a synthesis of theoretical and methodological work in a range of fields, including feminist film criticism and theory, and remains at once connected to and distinct from feminist approaches to studying film. The commercial dominance of the US television system required that feminist television critics explore the “popular” to a degree less evident in US feminist film criticism, although feminist film critics have examined mainstream film texts with tools similar to those used by feminist television critics in other national contexts (Joanne Hollows 2000; Jacinda Read 2000; Yvonne Tasker 1993, 1998). Understanding the relationship between varied areas of feminist media scholar- ship—their necessary divergences and their commonalities—aids in developing increasingly sophisticated theory and in responding to technological, socio-cultural, and theoretical changes. The transition to digital formats and hybrid delivery systems has begun to alter traditions of both “film” and “television,” while postfeminist approaches have reinvigorated feminist media debates. Additionally, new media have established a place in popular use and academic criticism. This context makes it more crucial than ever to address the reasons for medium-specific feminist approaches as well as to consider what can be gained through shared conversations. -

Medical Television Programmes and Patient Behaviour

Gesnerus 76/2 (2019) 225–246, DOI: 10.24894/Gesn-en.2019.76011 Doing the Work of Medicine? Medical Television Programmes and Patient Behaviour Tim Boon, Jean-Baptiste Gouyon Abstract This article explores the contribution of television programmes to shaping the doctor-patient relationship in Britain in the Sixties and beyond. Our core proposition is that TV programmes on medicine ascribe a specifi c position as patients to viewers. This is what we call the ‘Inscribed Patient’. In this ar- ticle we discuss a number of BBC programmes centred on medicine, from the 1958 ‘On Call to a Nation’; to the 1985 ‘A Prize Discovery’, to examine how television accompanied the development of desired patient behaviour during the transition to what was dubbed “Modern Medicine” in early 1970s Brit- ain. To support our argument about the “Inscribed Patient”, we draw a com- parison with natural history programmes from the early 1960s, which simi- larly prescribed specifi c agencies to viewers as potential participants in wild- life fi lmmaking. We conclude that a ‘patient position’ is inscribed in biomedical television programmes, which advance propositions to laypeople about how to submit themselves to medical expertise. Inscribed patient; doctor-patient relationship; biomedical television pro- grammes; wildlife television; documentary television; BBC Horizon Introduction Television programmes on medical themes, it is true, are only varieties of tele- vision programming more broadly, sharing with those others their programme styles and ‘grammar’. But they -

Unit 2 Setting

History of Television Broadcasting Unit 2 Unit-2: HISTORY OF TELEVISION BROAD- CASTING UNIT STRUCTURE 2.1 Learning Objectives 2.2 Introduction 2.3 Origin and Development of Television 2.4 Transmission of Television System 2.5 Broadcasting 2.6 Colour Television 2.7 Cable Television 2.8 Television News 2.9 Digital Television 2.10 High Definition Television 2.11 Let Us Sum Up 2.12 Further Reading 2.13 Answers to Check Your Progress 2.14 Model Questions 2.1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES After going through this unit, you will be able to - describe the evolution of television discuss the discoveries made by the pioneer of television inventors analyse the television technology development list the recent trend of Digital Television 2.2 INTRODUCTION In the previous unit we were introduced to the television medium, its features and its impact and reach. The unit also provides the distinctions between television and the audio medium. In this unit we shall discuss Electronic Media-Television 23 Unit 2 History of Television Broadcasting about the overview ofthe history of television, inventions, early technological development and the new trends in the television industry around the globe. 2.3 ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF TELEVISION Television has become one of the important parts of our everyday life. It is a general known fact that television is not only providing the news and information but it is also entertaining us with its variety of programme series and shows. A majority of home-makers cannot think about spending theirafternoon leisure time withoutthe dose of daily soap opera; a concerned citizen cannot think of skipping the prime time in news channel or a sports lover in India cannot miss a live cricket match. -

The Edward R. Murrow of Docudramas and Documentary

Media History Monographs 12:1 (2010) ISSN 1940-8862 The Edward R. Murrow of Docudramas and Documentary By Lawrence N. Strout Mississippi State University Three major TV and film productions about Edward R. Murrow‟s life are the subject of this research: Murrow, HBO, 1986; Edward R. Murrow: This Reporter, PBS, 1990; and Good Night, and Good Luck, Warner Brothers, 2005. Murrow has frequently been referred to as the “father” of broadcast journalism. So, studying the “documentation” of his life in an attempt to ascertain its historical role in supporting, challenging, and/or adding to the collective memory and mythology surrounding him is important. Research on the docudramas and documentary suggests the depiction that provided the least amount of context regarding Murrow‟s life (Good Night) may be the most available for viewing (DVD). Therefore, Good Night might ultimately contribute to this generation (and the next) having a more narrow and skewed memory of Murrow. And, Good Night even seems to add (if that is possible) to Murrow‟s already “larger than life” mythological image. ©2010 Lawrence N. Strout Media History Monographs 12:1 Strout: Edward R. Murrow The Edward R. Murrow of Docudramas and Documentary Edward R. Murrow officially resigned from Life and Legacy of Edward R. Murrow” at CBS in January of 1961 and he died of cancer AEJMC‟s annual convention in August 2008, April 27, 1965.1 Unquestionably, Murrow journalists and academicians devoted a great contributed greatly to broadcast journalism‟s deal of time revisiting Edward R. Murrow‟s development; achieved unprecedented fame in contributions to broadcast journalism‟s the United States during his career at CBS;2 history. -

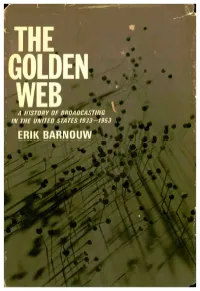

The-Golden-Web-Barnouw.Pdf

THE GOLDEN WE; A HISTORY OF BROADCASTING IN THE UNITED STA TES 1933-195 r_ ERIK BARNOUW s 11*. !,f THE GOLDEN WEB A History of Broadcasting in the United States Volume II, 1933 -1953 ERIK BARNOUW The giant broadcasting networks are the "golden web" of the title of this continuation of Mr. Bamouw's definitive history of Amer- ican broadcasting. By 1933, when the vol- ume opens, the National Broadcasting Com- pany was established as a country -wide network, and the Columbia Broadcasting System was beginning to challenge it. By 1953, at the volume's close, a new giant, television, had begun to dominate the in- dustry, a business colossus. Mr. Barnouw vividly evokes an era during which radio touched almost every Ameri- can's life: when Franklin D. Roosevelt's "fireside chats" helped the nation pull through the Depression and unite for World War II; other political voices -Mayor La Guardia, Pappy O'Daniel, Father Coughlin, Huey Long -were heard in the land; and overseas news -broadcasting hit its stride with on-the -scene reports of Vienna's fall and the Munich Crisis. The author's descrip- tion of the growth of news broadcasting, through the influence of correspondents like Edward R. Murrow, H. V. Kaltenborn, William L. Shirer, and Eric Sevareid, is particularly illuminating. Here are behind- the -scenes struggles for power -the higher the stakes the more im- placable- between such giants of the radio world as David Sarnoff and William S. Paley; the growing stranglehold of the ad- vertising agencies on radio programming; and the full story of Edwin Armstrong's suit against RCA over FM, with its tragic after- math. -

Television Shows

Libraries TELEVISION SHOWS The Media and Reserve Library, located on the lower level west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 1950s TV's Greatest Shows DVD-6687 Age and Attitudes VHS-4872 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs Age of AIDS DVD-1721 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs Age of Kings, Volume 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6678 Discs 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs Age of Kings, Volume 2 (Discs 4-5) DVD-6679 Discs 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs Alfred Hitchcock Presents Season 1 DVD-7782 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs Alias Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6165 Discs 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs Alias Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6165 Discs 30 Days Season 1 DVD-4981 Alias Season 2 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6171 Discs 30 Days Season 2 DVD-4982 Alias Season 2 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6171 Discs 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Alias Season 3 (Discs 1-4) DVD-7355 Discs 30 Rock Season 1 DVD-7976 Alias Season 3 (Discs 5-6) DVD-7355 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.1 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 4 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6177 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 4 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6177 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 4-5) c.1 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 5 DVD-6183 90210 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-5583 Discs All American Girl DVD-3363 Abnormal and Clinical Psychology VHS-3068 All in the Family Season One DVD-2382 Abolitionists DVD-7362 Alternative Fix DVD-0793 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

The Work of the Critic

CHAPTER 1 The Work of the Critic Oh, gentle lady, do not put me to’t. For I am nothing if not critical. —Iago to Desdemona (Shakespeare, Othello, Act 2, Scene I) INTRODUCTION What is the advantage of knowing how to perform television criticism if you are not going to be a professional television critic? The advantage to you as a television viewer is that you will not only be able to make informed judgment about the television programs you watch, but also you will better understand your reaction and the reactions of others who share the experience of watching. Critical acuity enables you to move from casual enjoyment of a television program to a fuller and richer understanding. A viewer who does not possess critical viewing skills may enjoy watching a television program and experience various responses to it, such as laughter, relief, fright, shock, tension, or relaxation. These are fun- damental sensations that people may get from watching television, and, for the most part, viewers who are not critics remain at this level. Critical awareness, however, enables you to move to a higher level that illuminates production practices and enhances your under- standing of culture, human nature, and interpretation. Students studying television production with ambitions to write, direct, edit, produce, and/or become camera operators will find knowledge of television criticism necessary and useful as well. Television criticism is about the evaluation of content, its context, organiza- tion, story and characterization, style, genre, and audience desire. Knowledge of these concepts is the foundation of successful production. THE ENDS OF CRITICISM Just as critics of books evaluate works of fiction and nonfiction by holding them to estab- lished standards, television critics utilize methodology and theory to comprehend, analyze, interpret, and evaluate television programs. -

The Place of Voiceover in Academic Audiovisual Film and Television Criticism

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES www.necsus-ejms.org The Place of Voiceover in Academic Audiovisual Film and Television Criticism Ian Garwood NECSUS 5 (2), Autumn 2016: 271–275 URL: https://necsus-ejms.org/the-place-of-voiceover-in- audiovisual-film-and-television-criticism Keywords: audiovisual essay, criticism, film, television, voiceover The line between academic and non-scholarly video- graphic film criticism The production of The Place of Voiceover in Academic Audiovisual Film and Television Criticism (2016) coincided with the release of two books focused on videographic film studies: The Videographic Essay – Criticism in Sound and Image, edited by Christian Keathley and Jason Mittell;[1] and Film Studies in Motion: From Audiovisual Essay to Academic Research Video, by Thomas van den Berg and Miklos Kiss.[2] The most recent instalments in a rich vein of writing exploring the potential of audiovisual research within screen stud- ies,[3] these two works set out distinctive (audio)visions of the format. A NECSUS – EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES shared point of deliberation is the balance the ‘academic’ video essay should strike in its adherence to traditional scholarly virtues and its exploration of the audiovisual form’s more ‘poetic’ possibilities. Essentially, Keathley and Mittell encourage film studies academics to loosen up; they begin with a description of editing exercises that invite participants to play with sounds and images in ways to help them ‘unlearn’ their usual habits of academic research and presentation. Van den Berg and Kiss, by contrast, argue po- lemically for a considerable tightening of practice in video essay work, if it is to be considered academically credible. -

The Emergence of Digital Documentary Filmmaking in the United States

Academic Forum 30 2012-13 Conclusion These studies are the second installment of a series which I hope to continue. Baseball is unique among sports in the way that statistics play such a central role in the game and the fans' enjoyment thereof. The importance of baseball statistics is evidenced by the existence of the Society for American Baseball Research, a scholarly society dedicated to studying baseball. References and Acknowledgements This work is made much easier by Lee Sinins' Complete Baseball Encyclopedia, a wonderful software package, and www.baseball-reference.com. It would have been impossible without the wonderful web sites www.retrosheet.org and www.sabr.org which give daily results and information for most major league games since the beginning of major league baseball. Biography Fred Worth received his B.S. in Mathematics from Evangel College in Springfield, Missouri in 1982. He received his M.S. in Applied Mathematics in 1987 and his Ph.D. in Mathematics in 1991 from the University of Missouri-Rolla where his son is currently attending school. He has been teaching at Henderson State University since August 1991. He is a member of the Society for American Baseball Research, the Mathematical Association of America and the Association of Christians in the Mathematical Sciences. He hates the Yankees. The Emergence of Digital Documentary Filmmaking in the United States Paul Glover, M.F.A. Associate Professor of Communication Abstract This essay discusses documentary filmmaking in the United States and Great Britain throughout the 20 th century and into the 21 st century. Technological advancements have consistently improved filmmaking techniques, but they have also degraded the craft as the saturation of filmmakers influence quality control and the preservation of “cinema verite” or “truth in film.” This essay’s intention is not to decide which documentaries are truthful and good (there are too many to research) but rather discuss certain documentarians and the techniques they used in their storytelling methods. -

Affluent Americans and the New Golden Age of Tv

IPSOS AFFLUENT INTELLIGENCE: AFFLUENT AMERICANS AND THE NEW GOLDEN AGE OF TV © 2019 Ipsos. All rights reserved. Contains Ipsos' Confidential and Proprietary information and may not be disclosed or reproduced without the prior written consent of Ipsos. STREAMING NOW – THE GOLDEN AGE OF AFFLUENT TV It’s no secret that the world of TV content and viewing has been undergoing considerable and on-going change for some time, causing a wholesale redefinition of how audiences experience watching it – not to mention the impact these new ways of watching has had on people’s lifestyles. This revolution can be attributed to What is an many factors – from the massive proliferation in content and channels, to the growth and availability of bandwidth capacity and Affluencer? speed, to the rapid rise of mobile devices which changed what “watching” meant, to the launch of streaming services which Affluent influencers— removed the wires and cables. Add to that the coming-of-age of Affluencers— drive most the digitally native Millennials and you have a world of TV that categories. Affluencers are looks nothing like it did five years ago, let alone 25. enthusiastic consumers of category-related information and have disproportionately high In this paper we’ll look at the various behaviors, preferences and purchase intent. They’re heavy attitudes driving the “new TV” category - and most importantly spenders who are the first to try for media and category service providers, we’ll look at the new offerings. And their affluent demographics and category segments posing the networks depend on them for greatest revenue opportunities. -

Drama Co- Productions at the BBC and the Trade Relationship with America from the 1970S to the 1990S

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output ’Running a brothel from inside a monastery’: drama co- productions at the BBC and the trade relationship with America from the 1970s to the 1990s http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/56/ Version: Full Version Citation: Das Neves, Sheron Helena Martins (2013) ’Running a brothel from inside a monastery’: drama co-productions at the BBC and the trade relationship with America from the 1970s to the 1990s. MPhil thesis, Birkbeck, University of Lon- don. c 2013 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email BIRKBECK, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART AND SCREEN MEDIA MPHIL VISUAL ARTS AND MEDIA ‘RUNNING A BROTHEL FROM INSIDE A MONASTERY’: DRAMA CO-PRODUCTIONS AT THE BBC AND THE TRADE RELATIONSHIP WITH AMERICA FROM THE 1970s TO THE 1990s SHERON HELENA MARTINS DAS NEVES I hereby declare that this is my own original work. August 2013 ABSTRACT From the late 1970s on, as competition intensified, British broadcasters searched for new ways to cover the escalating budgets for top-end drama. A common industry practice, overseas co-productions seems the fitting answer for most broadcasters; for the BBC, however, creating programmes that appeal to both national and international markets could mean being in conflict with its public service ethos. Paradoxes will always be at the heart of an institution that, while pressured to be profitable, also carries a deep-rooted disapproval of commercialism.