Conceptualisms, Old and New Marjorie Perloff Before Conceptual Art Became Prominent in the Late 1960S, There Was Already, So

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All These Post-1965 Movements Under the “Conceptual Art” Umbrella

All these post-1965 movements under the “conceptual art” umbrella- Postminimalism or process art, Site Specific works, Conceptual art movement proper, Performance art, Body Art and all combinations thereof- move the practice of art away from art-as-autonomous object, and art-as-commodification, and towards art-as-experience, where subject becomes object, hierarchy between subject and object is critiqued and intersubjectivity of artist, viewer and artwork abounds! Bruce Nauman, Live-Taped Video Corridor, 1970, Conceptual Body art, Postmodern beginning “As opposed to being viewers of the work, once again they are viewers in it.” (“Subject as Object,” p. 199) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9IrqXiqgQBo A Postmodern beginning: Body art and Performance art as critique of art-as-object recap: -Bruce Nauman -Vito Acconci focus on: -Chris Burden -Richard Serra -Carolee Schneemann - Hannah Wilke Chapter 3, pp. 114-132 (Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke, First Generation Feminism) Bruce Nauman, Bouncing Two Balls Between the Floor and Ceiling with Changing Rhythms, 1967-1968. 16mm film transferred to video (black and white, sound), 10 min. Body art/Performance art, Postmodern beginning- performed elementary gestures in the privacy of his studio and documented them in a variety of media Vito Acconci, Following Piece, 1969, Body art, Performance art- outside the studio, Postmodern beginning Video documentation of the event Print made from bite mark Vito Acconci, Trademarks, 1970, Body art, Performance art, Postmodern beginning Video and Print documentation -

VITO ACCONCI Born 1940 Bronx, New York

GRIEDER CONTEMPORARY VITO ACCONCI born 1940 Bronx, New York. Lives and works in Brooklyn, NY. 1962 Bachelor of Arts, Holy Cross College, Worcester, Massachusetts, US 1964 Master of Fine Arts, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, US Solo Exhibitions (selected) 2014 Vito Acconci: Now and Then, Grieder Contemporary, Zurich, CH 2012 Vito Acconci: Vito Acconci, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, US 2011 Vito Acconi, Galleria Fumagalli, Bergamo, IT 2010 AAA Talk Vito Acconci + Ai Weiwei: Artist in Conversation, Agnès b. Cinema, Wanchai, HK Early Works – Vito Acconci, Basis Frankfurt, Frankfurt/Main, DE Coinvolgimenti – Castello di Rivoli Museo d'Arte Contemporanea, Turin, IT Lobby-For-The-Time-Being, Bronx Museum of the Arts (BxMA), New York City, NY Le Corps Comme Sculpture – Vito Acconci, Musée Auguste Rodin, Paris, FR 2009 Vito Acconci: Language Works – Video, audio and poetry, Argos, Brussels, BE 2008 Vigilancia y control, Centro de Arte La regenta, las Palmas de Gran Canaria, ES Power Fields: Explorations in the Work of Vito Acconci, Slought Foundation, Philadelphia, PA, US 2005 Self/Sound/City, Foundation for Art and Creative Technology (FACT), Liverpool, UK Vito Hannibal Acconci Studio, Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, ES; Centro Atlantico de Arte Moderno, Las Palmas, Gran Canaria, ES; Stedelijk, Amsterdam, NL 2004 Diary of a Body, Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY Vito Hannibal Acconci Studio, Musee des Beaux Artes, Nantes, FR; MACBA, Barcelona, ES 2003 Rehearsals for Architecture, Kenny Schachter Rove, Perry St., New York, NY, US Acconci Studio – Slipping into the 21st Century, Pratt–Manhattan Gallery, New York, NY, US 2002 Vito Acconci/Acconci Studio: Acts Of Architecture, Milwaukee Museum of Art (Traveled to Aspen Art Museum, Miami Museum of Art 2001,Contemporary Art Museum Houston 2001) 2001 Vito Acconci, 11 Duke Street, London, UK Vito Acconci / Acconci Studio, Architectural Models, The Institute for the Cooperatic Research, New York, US, and Paris, FR Built, Unbuilt, Unbuildable. -

The Internet As Playground and Factory November 12–14, 2009 at the New School, New York City

FIRST IN A SERIES OF BIENNIAL CONFERENCES ABOUT THE POLITICS OF DIGITAL MEDIA THE INTERNET AS PLAYGROUND AND FACTORY NOVEMBER 12–14, 2009 AT THE NEW SCHOOL, NEW YORK CITY www.digitallabor.org The conference is sponsored by Eugene Lang College The New School for Liberal Arts and presented in cooperation with the Center for Transformative Media at Parsons The New School for Design, Yale Information Society Project, 16 Beaver Group, The New School for Social Research, The Change You Want To See, The Vera List Center for Art and Politics, New York University’s Council for Media and Culture, and n+1 Magazine. Acknowledgements General Event Support Lula Brown, Alison Campbell, Alex Cline, Conference Director Patrick Fannon, Keith Higgons, Geoff Trebor Scholz Kim, Ellen-Maria Leijonhufvud, Stephanie Lotshaw, Brie Manakul, Lindsey Medeiros, Executive Conference Production Farah Momin, Heather Potts, Katharine Trebor Scholz, Larry Jackson Relth, Jesse Ricke, Joumana Seikaly, Ndelea Simama, Andre Singleton, Lisa Conference Production Taber, Yamberlie Tavarez, Brandon Tonner- Deepthie Welaratna, Farah Momin, Connolly, Jolita Valakaite, Cynthia Wang, Julia P. Carrillo Deepthi Welaratna, Tatiana Zwerling Production of Video Series Voices from Registration Staff The Internet as Playground and Factory Alison Campbell, Alex Cline, Keith Higgons, Assal Ghawami Geoff Kim, Stephanie Lotshaw, Brie Manakul, Overture Video Lindsey Medeiros, Heather Potts, Jesse Assal Ghawami Ricke, Joumana Seikaly, Andre Singleton, Deepthi Welaratna, Tatiana Zwerling Video -

Defamiliarization: Flarf, Conceptual Writing, and Using Flawed Software Tools As Creative Partners Richard P. Gabriel*

Knowledge Management & E-Learning: An International Journal, Vol.4, No.2. 134 Defamiliarization: Flarf, conceptual writing, and using flawed software tools as creative partners Richard P. Gabriel* IBM Research 3636 Altamont Way, Redwood City CA 94062, USA E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract: One form of creativity uses defamiliarization, a mechanism that frees the brain from its rational shackles and permits the abducing brain to run free. Mistakes and flaws in several software tools are shown to be the starting points for increased creativity and better art, and a theory explaining the phenomenon is proposed. Keywords: Writing; Poetry; Creativity; Flarf Biographical notes: Richard P. Gabriel received a PhD in Computer Science from Stanford University in 1981, and an MFA in Poetry from Warren Wilson College in 1998. He has been a researcher at Stanford University, company president and Chief Technical Officer at Lucid, Inc., vice president of Development at ParcPlace-Digitalk, a management consultant for several startups, a Distinguished Engineer at Sun Microsystems, and Consulting Professor of Computer Science at Stanford University. He is an ACM Fellow. He is a researcher at IBM Research, looking into the architecture, design, and implementation of extraordinarily large, self-sustaining systems as well as development techniques for building them. Until recently he was President of the Hillside Group, a nonprofit that nurtures the software patterns community by holding conferences, publishing books, -

I – Introduction

QUEERING PERFORMATIVITY: THROUGH THE WORKS OF ANDY WARHOL AND PERFORMANCE ART by Claudia Martins Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2008 I never fall apart, because I never fall together. Andy Warhol The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back again CEU eTD Collection CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS..........................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................v ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................vi CHAPTER 1 - Introduction .............................................................................................7 CHAPTER 2 - Bringing the body into focus...................................................................13 CHAPTER 3 - XXI century: Era of (dis)embodiment......................................................17 Disembodiment in Virtual Spaces ..........................................................18 Embodiment Through Body Modification................................................19 CHAPTER 4 - Subculture: Resisting Ajustment ............................................................22 CHAPTER 5 - Sexually Deviant Bodies........................................................................24 CHAPTER 6 - Performing gender.................................................................................29 -

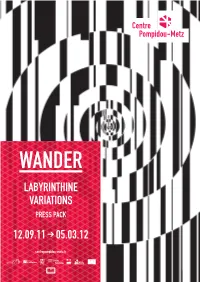

Labyrinthine Variations 12.09.11 → 05.03.12

WANDER LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS PRESS PACK 12.09.11 > 05.03.12 centrepompidou-metz.fr PRESS PACK - WANDER, LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION .................................................... 02 2. THE EXHIBITION E I TH LAByRINTH AS ARCHITECTURE ....................................................................... 03 II SpACE / TImE .......................................................................................................... 03 III THE mENTAL LAByRINTH ........................................................................................ 04 IV mETROpOLIS .......................................................................................................... 05 V KINETIC DISLOCATION ............................................................................................ 06 VI CApTIVE .................................................................................................................. 07 VII INITIATION / ENLIgHTENmENT ................................................................................ 08 VIII ART AS LAByRINTH ................................................................................................ 09 3. LIST OF EXHIBITED ARTISTS ..................................................................... 10 4. LINEAgES, LAByRINTHINE DETOURS - WORKS, HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOgICAL ARTEFACTS .................... 12 5.Om C m ISSIONED WORKS ............................................................................. 13 6. EXHIBITION DESIgN ....................................................................................... -

A Master's Exhibition of Sculpture Presented to The

TRANSPORTRAIT ____________ A Master’s Exhibition of Sculpture Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in Art ____________ by Trevor Earl Lalaguna Spring 2011 TRANSPORTRAIT A Master’s Exhibition by Trevor Earl Lalaguna Spring 2011 APPROVED BY THE DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND VICE PROVOST FOR RESEARCH: Katie Milo, Ed.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: _________________________________ _________________________________ Cameron G. Crawford, M.F.A. Sheri D. Simons, M.F.A., Chair Graduate Coordinator _________________________________ James A. Kuiper, M.F.A. DEDICATION This project is inspired by and dedicated to my fiancé and my family; I would also like to extend my dedication to the twelve adopting parents who allowed my project to live on and of course my babies. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the amazing faculty at CSU Chico for opening my eyes to the art world beyond my sketchbook. I thank my committee chair and good friend Sheri Simons, for always pushing my thoughts and creations to the edge. My committee members Elise Archias for bringing a love for art history into my life and giving me a sense of belonging, James Kuiper for being playful, intelligent and fresh thinking, Michael Bishop for his support in and out of school and giving me the opportunity and guidance to achieve this degree. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Dedication.................................................................................................................. -

Aware: Art Fashion Identity, Roya

58 Aware: Art Fashion Identity 59 The third GSK Contemporary exhibition at the RA’s Burlington Gardens galleries tackles the ecological, social and political influence of fashion on art. Co-curator, artist and designer Lucy Orta tells Ben Luke what’s in store for the show Fashion statements Andreas Gursky’s Kuwait Stock Exchange (2007, Gabi Scardi and the RA’s Kathleen Soriano. Orta years of thinking about the interface between opposite) is an epic and enigmatic work by this featured in ‘Earth’, alongside her husband and art and fashion. She studied fashion design at German master of photography. Shot from a collaborator Jorge, showing Antarctic Village, No Nottingham Polytechnic in the mid-1980s, high vantage point typical of Gursky’s work, the Borders (2007), a tent covered in a variety of specialising in knitwear design, but became picture takes an overview of the trading floor national flags. She recognised that GSK disillusioned with fashion’s extreme where hundreds of men are milling about Contemporary also offered the opportunity to extravagance soon afterwards and began to reading screens and talking either amongst explore a fresh ecological sensibility in fashion. make art. She has since trodden the line themselves or on the phone. between the two disciplines, influencing the What stands out is their uniform of flowing In splicing apparently fashion world with works such as Refuge Wear white gowns. These men are dressed not in the – Habitent (1992-93), a shiny silver creation suits that we associate with the City and Wall incongruous images of different which is both tent and garment, while showing Street, but in traditional, ankle-length thawb in galleries across the world. -

Laynie Browne Laynie Please Bernadette

Laynie Browne a ConCeptuaL assemBLage an introduCtion To work mine end upon their senses that This airy charm is for, I’ll break my staff, Bury it certain fathoms in the earth, And deeper than did ever plummet sound I’ll drown my book. - Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act V Scene I, Prospero Looking for a title for this collection I turned first to the work of Bernadette Mayer, and found in her collection, The Desires of Mothers to 0: Introduction Please Others in Letters, the title “I’ll Drown My Book.” The process of opening Mayer to find Shakespeare reframed seems particularly fitting in the sense that conceptual writing often involves a recasting of the familiar and the found. In Mayer’s hands, the phrase “I’ll Drown My Book” becomes an unthinkable yet necessary act. This combination of BROWNE BROWNE unthinkable, or illogical, and necessary, or obligatory, also speaks to ways that the writers in this collection seek to unhinge and re-examine previous assumptions about writing. Thinking and performance are not separate from process and presentation of works. If a book breathes it 14 can also drown, and in the act of drowning is a willful attempt to create a book which can awake the unexpected—not for the sake of surprise, but because the undertaking was necessary for the writer in order to uproot, dismantle, reforge, remap or find new vantages and entrances to well trodden or well guarded territory. My contemporaries for the most part have often been distinguished by their lack of camps, categories, or movements. -

Christian Bök's Xenotext Experiment, Conceptual Writing and the Subject

Christian Bök's Xenotext Experiment, Conceptual Writing and the Subject-of-No- Subjectivity: "Pink Faeries and Gaudy Baubles" Dr Isabel Waidner (University of Roehampton, UK) Keywords Xenotext Experiment; conceptual writing; feminist science and technology studies; subject-of- no-subjectivity; avant-garde poetics Abstract Despite the wide impact of transdisciplinary scholarship that has theorised the interconnectedness of literature and science not least within the pages of this journal1, this article argues that the Canadian poet Christian Bök's Xenotext Experiment2 (and conceptual writing in general) reproduces historical epistemologies (including positivism and relativism) 1 Melissa Littlefield and Rajani Sudan, "Editorial Statement", Configurations, 20:3 (2012): pp. 209–212. 2 Christian Bök, "The Xenotext Experiment", SCRIPT-Ed 5:2 (2008): pp. 227-231. 1 that rely on the presumption of disciplinary autonomy. In the sciences, these epistemologies are connected to sociocultural and economic power, extreme resistance to criticality, and the production of normative subject and object positions (including what I term the subject-of-no- subjectivity on the one hand; and the passive, inert object of scientific positivism on the other). The article explores the implications, problems, and affordances of reproducing historical epistemologies in conceptual writing. The key argument is that the reproduction of historical epistemologies in the disciplinary context of literature yields avant-garde credentials, marginalising often content-led experimental -

Reconceiving the Actual in Digital Art and Poetry

humanities Article Code and Substrate: Reconceiving the Actual in Digital Art and Poetry Burt Kimmelman Department of Humanities, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, NJ 07102, USA; [email protected] Received: 12 December 2016; Accepted: 5 July 2017; Published: 14 July 2017 Abstract: The quality of digital poetry or art—not merely as contained within our aesthetic reaction to digitally expressive works but as well our intellectual grounding in them—suggests that the digital’s seemingly ephemeral character is an indication of its lack of an apparently material existence. While, aesthetically, the digital’s ephemerality lies in the very fact of the digitally artistic enterprise, the fact is that its material substrate is what makes the aesthetic pleasure we take in it possible. When we realize for ourselves the role played by this substrate, furthermore, a paradox looms up before us. The fact is that we both enjoy, and in some sense separately understand the artwork comprehensively and fully; we also allow ourselves to enter into an ongoing conversation about the nature of the physical world. This conversation is not insignificant for the world of art especially, inasmuch as art depends upon the actual materials of the world—even digital art—and, too, upon our physical engagement with the art. Digital poetry and art, whose dynamic demands the dissolution of the line that would otherwise distinguish one from the other, have brought the notion of embodiment to the fore of our considerations of them, and here is the charm, along with the paradoxical strength, of digital art and poetry: it is our physical participation in them that makes them fully come into being. -

Kate Gilmore

Kate Gilmore VIDEO CONTAINER: TOUCH CINEMA KNIGHT EXHIBITION SERIES Ursula Mayer, Gonda, 2012, Film still On May 15, 2014, Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami (MOCA) presents “Video Container: Touch Cinema,” a presentation of single-channel video work by contemporary artists who investigate the material and metaphysical presence of the body as it relates to issues of identity and sexuality. The second edition of a new MOCA video series exploring topical issues in contemporary art making, “Video Container” reflects the museum’s ongoing commitment to presenting and contextualizing experimental and critical practices, and to providing a platform for interdisciplinary media and discursive content. The program series is made possible by an endowment to the museum by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. “Video Container: Touch Cinema” features videos by leading contemporary artists including: Vito Acconci, Bas Jan Ader, Sadie Benning, Shezad Dawood, Harry Dodge, Kate Gilmore, Maryam Jafri, Mike Kelley & Paul McCarthy, Ursula Mayer, Alix Pearlstein, Pipilotti Rist, Carolee Schneemann, Frances Stark, VALIE EXPORT, and Hannah Wilke, among others. The exhibition borrows its title from an iconic recording of a 1968 guerrilla performance by VALIE EXPORT, in which the artist attached a miniature curtained “movie theater” to her bare chest and invited passersby on the street to reach in. Conflating the space of the theater with her own body, EXPORT’s performance emphasized the powerful and contested nature of viewership and interaction. Ranging from performance documentation to abstract shorts and long-form narratives, the artists in “Video Container: Touch Cinema” expand upon themes related to VALIE EXPORT’s seminal piece.