Bobby Fischer in Socio-Cultural Perspective: Application of Hiller’S (2011) Multi-Layered Chronological Chart Methodology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65 COMPUTER ANALYSIS OF WORLD CHESS CHAMPIONS1 Matej Guid2 and Ivan Bratko2 Ljubljana, Slovenia ABSTRACT Who is the best chess player of all time? Chess players are often interested in this question that has never been answered authoritatively, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. In this contribution, we attempt to make such a comparison. It is based on the evaluation of the games played by the World Chess Champions in their championship matches. The evaluation is performed by the chess-playing program CRAFTY. For this purpose we slightly adapted CRAFTY. Our analysis takes into account the differences in players' styles to compensate the fact that calm positional players in their typical games have less chance to commit gross tactical errors than aggressive tactical players. Therefore, we designed a method to assess the difculty of positions. Some of the results of this computer analysis might be quite surprising. Overall, the results can be nicely interpreted by a chess expert. 1. INTRODUCTION Who is the best chess player of all time? This is a frequently posed and interesting question, to which there is no well founded, objective answer, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. With the emergence of high-quality chess programs a possibility of such an objective comparison arises. However, so far computers were mostly used as a tool for statistical analysis of the players' results. Such statistical analyses often do neither reect the true strengths of the players, nor do they reect their quality of play. -

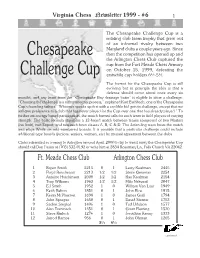

1999/6 Layout

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

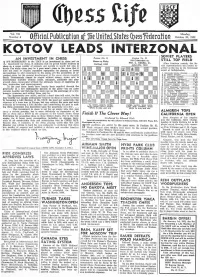

Kolov LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS an INVESTMENT in CHESS Po~;T;On No

Vol. Vll Monday; N umber 4 Offjeitll Publication of me Unttecl States (bessTederation October 20, 1952 KOlOV LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS AN INVESTMENT IN CHESS Po~;t;on No. 91 POI;l;"n No. 92 IFE MEMBERSHIP in the USCF is an investment in chess and an Euwe vs. Flohr STILL TOP FIELD L investment for chess. It indicates that its proud holder believes in C.1rIbad, 1932 After fOUl't~n rounds, the S0- chess ns a cause worthy of support, not merely in words but also in viet rcpresentatives still erowd to deeds. For while chess may be a poor man's game in the sense that it gether at the top in the Intel'l'onal does not need or require expensive equipment fm' playing or lavish event at Saltsjobaden. surroundings to add enjoyment to the game, yet the promotion of or· 1. Alexander Kot()v (Russia) .w._.w .... 12-1 ganized chess for the general development of the g'lmc ~ Iway s requires ~: ~ ~~~~(~tu(~~:I;,.i ar ·::::~ ::::::::::~ ~!~t funds. Tournaments cannot be staged without money, teams sent to international matches without funds, collegiate, scholastic and play· ;: t.~h!"'s~~;o il(\~::~~ ry i.. ··::::::::::::ij ); ~.~ ground chess encouraged without the adequate meuns of liupplying ad· 6. Gidcon S tahl ~rc: (Sweden) ...... 81-5l vice, instruction and encouragement. ~: ~,:ct.~.:~bG~~gO~~(t3Ji;Oi· · ·:::: ::::::7i~~ In the past these funds have largely been supplied through the J~: ~~j~hk Elrs'l;~san(A~~;t~~~ ) ::::6i1~ generosity of a few enthusiastic patrons of the game-but no game 11. -

Regulations for the FIDE World Chess Cup 2015 1

Regulations for the FIDE World Chess Cup 2015 1. Organisation 1.1 The FIDE World Chess Cup (World Cup) is an integral part of the World Championship Cycle 2014-2016. 1.2 Governing Body: the World Chess Federation (FIDE). For the purpose of creating the regulations, communicating with the players and negotiating with the organisers, the FIDE President has nominated a committee, hereby called the FIDE Commission for World Championships and Olympiads (hereinafter referred to as WCOC) 1.3 FIDE, or its appointed commercial agency, retains all commercial and media rights of the World Chess Cup 2015, including internet rights. 1.4 Upon recommendation by the WCOC, the body responsible for any changes to these Regulations is the FIDE Presidential Board. 2. Qualifying Events for World Cup 2015 2. 1. National Chess Championships - National Chess Championships are the responsibility of the Federations who retain all rights in their internal competitions. 2. 2. Zonal Tournaments - Zonals can be organised by the Continents according to their regulations that have to be approved by the FIDE Presidential Board. 2. 3. Continental Chess Championships - The Continents, through their respective Boards and in co-operation with FIDE, shall organise Continental Chess Championships. The regulations for these events have to be approved by the FIDE Presidential Board nine months before they start if they are to be part of the qualification system of the World Chess Championship cycle. 2. 3. 1. FIDE shall guarantee a minimum grant of USD 92,000 towards the total prize fund for Continental Championships, divided among the following continents: 1. Americas 32,000 USD (minimum prize fund in total: 50,000 USD) 2. -

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

Chess Viewer the Power of XSL Lies in Its Ability to Perform Radical Transformations of the XML Data Source

DEVELOPER'S ZONE SHOP SEARCH Products Demos Stories Solutions Support Download Customers Partners Company Sitemap Chess Viewer The power of XSL lies in its ability to perform radical transformations of the XML data source. This page contains yet another proof for this fact: you can build a chessgame viewer with a stylesheet! The source document is a transcription of a chess game played by Garry Kasparov against a chess supercomputer -- IBM Deep Blue. The game is encoded in a form resembling the well-known Portable Game Notation (PGN) format. The source is very compact: a sample game on this page [DeepBlue.xml] is less than 4 kBytes in size. The stylesheet converts this arid text into a sequence of board diagrams, drawing every intermediate position as a graphical image (a special chess font is used). Applying a 23 kB stylesheet [chess.xsl], we get a 415 kBytes (!) FO stream [DeepBlue.fo]. These numbers give an idea of how deep the transformation is. The final step of the whole procedure consists in converting the result into PDF using XEP. The resulting PDF file [DeepBlue.pdf] is much smaller than the source FO stream -- less than 90 kBytes. (XEP implements PDF compression). We hope XSL fans will enjoy this example; and XSL foes will acknowledge its power! More chess games created by the same stylesheet: Description FO Source PDF PostScript Fischer-Euwe.xml Fischer-Euwe.fo Fischer-Euwe.pdf Fischer-Euwe.ps Robert Fischer - Max Euwe Fischer-Tal.xml Fischer-Tal.fo Fischer-Tal.pdf Fischer-Tal.ps Robert Fischer - Mikhail Tal Kasparov-Karpov.xml Kasparov-Karpov.fo Kasparov-Karpov.pdf Kasparov-Karpov.ps Garry Kasparov - Anatoly Karpov Note: We have used an unabridged chess notation; the original PGN data are even more concise.We know it is possible to process even the short chess notation by XSL, and gladly leave this exercise to volunteers . -

Opening Moves - Player Facts

DVD Chess Rules Chess puzzles Classic games Extras - Opening moves - Player facts General Rules The aim in the game of chess is to win by trapping your opponent's king. White always moves first and players take turns moving one game piece at a time. Movement is required every turn. Each type of piece has its own method of movement. A piece may be moved to another position or may capture an opponent's piece. This is done by landing on the appropriate square with the moving piece and removing the defending piece from play. With the exception of the knight, a piece may not move over or through any of the other pieces. When the board is set up it should be positioned so that the letters A-H face both players. When setting up, make sure that the white queen is positioned on a light square and the black queen is situated on a dark square. The two armies should be mirror images of one another. Pawn Movement Each player has eight pawns. They are the least powerful piece on the chess board, but may become equal to the most powerful. Pawns always move straight ahead unless they are capturing another piece. Generally pawns move only one square at a time. The exception is the first time a pawn is moved, it may move forward two squares as long as there are no obstructing pieces. A pawn cannot capture a piece directly in front of him but only one at a forward angle. When a pawn captures another piece the pawn takes that piece’s place on the board, and the captured piece is removed from play If a pawn gets all the way across the board to the opponent’s edge, it is promoted. -

Mirotvor Schwartz CHESS PLAYERS on STAMPS

Mirotvor Schwartz CHESS PLAYERS ON STAMPS This is a list of chess players depicted on stamps, along with the actual stamps. Each player’s name is clickable – it will take you to the player’s Wikipedia page (or, if one does not exist, to a different chess-related page), where you can view the player’s biography and details of their career. If a philatelic item depicts a specific chess contest, said contest is mentioned in italics following the item. For each chess player, a short biography is given. It includes two types of competitions: 1.World Championship and its affiliate contests (Candidates Tournament, Interzonal Tournament, World Cup, FIDE Grand Prix, FIDE Grand Swiss Tournament), as well as major team competitions (Olympiads, World Team Championship, European Team Championship). 2.An event depicted in my “Chess History on Stamps” collection, no matter how minor or seemingly insignificant. After each contest and year in a player’s biography, the following information is given in brackets: 1.The place in which the player (or their team) finished the competition. Note that “(?)” means the place is unknown at the time, while “(0)” means the player or the team was participating as a non- contestant. 2.In a team competition, the following personal achievements of the player: -- being the best player at their board (BB) -- showing the best individual performance of the tournament (BP) If an achievement is actually depicted on a stamp or a philatelic item, the year of said achievement is bolded. 1 EXAMPLE: Let’s look at Nino Batsiashvili: -

The Evects of Time Pressure on Chess Skill: an Investigation Into Fast and Slow Processes Underlying Expert Performance

Psychological Research (2007) 71:591–597 DOI 10.1007/s00426-006-0076-0 ORIGINAL ARTICLE The eVects of time pressure on chess skill: an investigation into fast and slow processes underlying expert performance Frenk van Harreveld · Eric-Jan Wagenmakers · Han L. J. van der Maas Received: 28 November 2005 / Accepted: 3 July 2006 / Published online: 22 December 2006 © Springer-Verlag 2006 Abstract The ability to play chess is generally Introduction assumed to depend on two types of processes: slow processes such as search, and fast processes such as One of the important challenges for cognitive science is pattern recognition. It has been argued that an increase to shed light on the processes that underlie expert in time pressure during a game selectively hinders the decision making. Across a wide range of Welds such as ability to engage in slow processes. Here we study the medical decision making and engineering, it has been eVect of time pressure on expert chess performance in shown that expertise involves both slow processes order to test the hypothesis that compared to weak such as selective search and fast processes such as the players, strong players depend relatively heavily on recognition of meaningful patterns (e.g., Ericsson & fast processes. In the Wrst study we examine the perfor- Staszewski 1989). This distinction between fast and slow mance of players of various strengths at an online chess processes is very applicable to the game of chess and server, for games played under diVerent time controls. therefore research on chess is of considerable impor- In a second study we examine the eVect of time con- tance for the understanding of expert performance. -

CHESS FEDERATION Newburgh, N.Y

Announcing an important new series of books on CONTEMPORARY CHESS OPENINGS Published by Chess Digest, Inc.-General Editor, R. G. Wade The first book in this current series is a fresh look at 's I IAN by Leonard Borden, William Hartston, and Raymond Keene Two of the most brilliant young ployers pool their talents with one of the world's well-established authorities on openings to produce a modern, definitive study of the King's Indian Defence. An essen tial work of reference which will help master and amateur alike to win more games. The King's Indian Defence has established itself as one of the most lively and populor openings and this book provides 0 systematic description of its strategy, tactics, and variations. Written to provide instruction and under standing, it contains well-chosen illustrative games from octuol ploy, many of them shown to the very lost move, and each with an analysis of its salient features. An excellent cloth-bound book in English Descriptive Notation, with cleor type, good diagrams, and an easy-to-follow format. The highest quality at a very reasonable price. Postpaid, only $4.40 DON'T WAIT-ORDER NOW-THE BOOK YOU MUST HAVE! FLA NINGS by Raymond Keene Raymond Keene, brightest star in the rising galaxy of young British players, was undefeated in the 1968 British Championship and in the 1968 Olympiad at Lugano. In this book, he posses along to you the benefit of his studies of the King's Indian Attack and the Reti, Catalan, English, and Benko Larsen openings. The notation is Algebraic, the notes comprehensive but easily understood and right to the point. -

No. 123 - (Vol.VIH)

No. 123 - (Vol.VIH) January 1997 Editorial Board editors John Roycrqfttf New Way Road, London, England NW9 6PL Edvande Gevel Binnen de Veste 36, 3811 PH Amersfoort, The Netherlands Spotlight-column: J. Heck, Neuer Weg 110, D-47803 Krefeld, Germany Opinions-column: A. Pallier, La Mouziniere, 85190 La Genetouze, France Treasurer: J. de Boer, Zevenenderdrffi 40, 1251 RC Laren, The Netherlands EDITORIAL achievement, recorded only in a scientific journal, "The chess study is close to the chess game was not widely noticed. It was left to the dis- because both study and game obey the same coveries by Ken Thompson of Bell Laboratories rules." This has long been an argument used to in New Jersey, beginning in 1983, to put the boot persuade players to look at studies. Most players m. prefer studies to problems anyway, and readily Aside from a few upsets to endgame theory, the give the affinity with the game as the reason for set of 'total information' 5-raan endgame their preference. Your editor has fought a long databases that Thompson generated over the next battle to maintain the literal truth of that ar- decade demonstrated that several other endings gument. It was one of several motivations in might require well over 50 moves to win. These writing the final chapter of Test Tube Chess discoveries arrived an the scene too fast for FIDE (1972), in which the Laws are separated into to cope with by listing exceptions - which was the BMR (Board+Men+Rules) elements, and G first expedient. Then in 1991 Lewis Stiller and (Game) elements, with studies firmly identified Noam Elkies using a Connection Machine with the BMR realm and not in the G realm. -

Anatoly Karpov INTRODUCTION

FOREWARD In December of 1998 as I was winning the first ever FIDE World Active Championship in Mazatlan Mexico, I noticed I had the same person working the chess wall board for my very difficult final matches versus Viktor Gavrikov and Roman Dzindzichashvili. Imagine my surprise as I was autographing a book, when he asked if I would consider an American second for the upcoming Candidates Quarter-final match with Hjartarson. The idea seemed interesting as more and more matches were taking place in English speaking countries, so I suggested we meet at the end of the event after the closing ceremonies. In checking with my team, we discovered in his youth, Henley had scored impressive wins versus Timman, Seirawan, Ribli, Miles, Short and others, followed by a very long gap. I also found it a good omen that Ron shared the December 5th birthday of my first trainer/mentor and very good friend Semyon Furman who passed in 1978. Throughout the nineties, Ron joined our team for matches with Anand, Timman (2), Yusupov, Gelfand, Kamsky and Kasparov. In “Win Like Karpov” Henley explains in a basic easy to understand level many of the strategies and tactics that brought me success at key moments in my career. I have contributed notes, commentary and photos to several key moments from my “Second Career” in the 1990’s when I achieved my highest ELO - 2780 and regained the FIDE World Championship. GM Henley has done an excellent job of identifying several key opening positions as well as certain types of recurring themes in my Classical Style of middlegame play.