Hip Hop from Italy and the Diaspora: a Report from the 41St Parallel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Document 543Kb

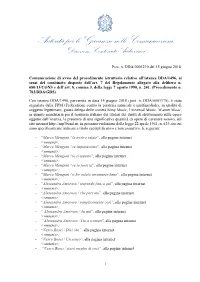

Autorità per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni Direzione Contenuti Audiovisivi Prot. n. DDA/0001210 del 15 giugno 2018 Comunicazione di avvio del procedimento istruttorio relativo all’istanza DDA/1496, ai sensi del combinato disposto dell’art. 7 del Regolamento allegato alla delibera n. 680/13/CONS e dell’art. 8, comma 3, della legge 7 agosto 1990, n. 241. (Procedimento n. 782/DDA/GDS) Con istanza DDA/1496, pervenuta in data 14 giugno 2018 (prot. n. DDA/0001175), è stata segnalata dalla FPM (Federazione contro la pirateria musicale e multimediale), in qualità di soggetto legittimato, giusta delega delle società Sony Music, Universal Music, Warner Music, in quanto mandataria per il territorio italiano dei titolari dei diritti di sfruttamento sulle opere oggetto dell’istanza, la presenza di una significativa quantità di opere di carattere sonoro, sul sito internet http://mp3band.ru, in presunta violazione della legge 22 aprile 1941, n. 633, tra cui sono specificamente indicate a titolo esemplificativo e non esaustivo, le seguenti: - “Marco Mengoni / la nostra estate”, alla pagina internet <omissis>; - “Marco Mengoni / se imparassimo”, alla pagina internet <omissis>; - “Marco Mengoni / io ti aspetto”, alla pagina internet <omissis>; - “Marco Mengoni / se io fossi te”, alla pagina internet <omissis>; - “Marco Mengoni / ti ho voluto veramente bene”, alla pagina internet <omissis>; - “Alessandra Amoroso / stupendo fino a qui”, alla pagina internet <omissis>; - “Alessandra Amoroso / che peccato”, alla pagina internet <omissis>; - “Alessandra Amoroso -

Is Hip Hop Dead?

IS HIP HOP DEAD? IS HIP HOP DEAD? THE PAST,PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF AMERICA’S MOST WANTED MUSIC Mickey Hess Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hess, Mickey, 1975- Is hip hop dead? : the past, present, and future of America’s most wanted music / Mickey Hess. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 (alk. paper) 1. Rap (Music)—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3531H47 2007 782.421649—dc22 2007020658 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2007 by Mickey Hess All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007020658 ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 ISBN-10: 0-275-99461-9 First published in 2007 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION 1 1THE RAP CAREER 13 2THE RAP LIFE 43 3THE RAP PERSONA 69 4SAMPLING AND STEALING 89 5WHITE RAPPERS 109 6HIP HOP,WHITENESS, AND PARODY 135 CONCLUSION 159 NOTES 167 BIBLIOGRAPHY 179 INDEX 187 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The support of a Rider University Summer Fellowship helped me com- plete this book. I want to thank my colleagues in the Rider University English Department for their support of my work. -

The Concert Hall As a Medium of Musical Culture: the Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19Th Century

The Concert Hall as a Medium of Musical Culture: The Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19th Century by Darryl Mark Cressman M.A. (Communication), University of Windsor, 2004 B.A (Hons.), University of Windsor, 2002 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology © Darryl Mark Cressman 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Darryl Mark Cressman Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) Title of Thesis: The Concert Hall as a Medium of Musical Culture: The Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19th Century Examining Committee: Chair: Martin Laba, Associate Professor Andrew Feenberg Senior Supervisor Professor Gary McCarron Supervisor Associate Professor Shane Gunster Supervisor Associate Professor Barry Truax Internal Examiner Professor School of Communication, Simon Fraser Universty Hans-Joachim Braun External Examiner Professor of Modern Social, Economic and Technical History Helmut-Schmidt University, Hamburg Date Defended: September 19, 2012 ii Partial Copyright License iii Abstract Taking the relationship -

Turkish-German Rap and Threatening Masculinity

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2020 Schieß, Bruder: Turkish-German Rap and Threatening Masculinity Manasi Deorah Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, European History Commons, Modern Languages Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, Other German Language and Literature Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Deorah, Manasi, "Schieß, Bruder: Turkish-German Rap and Threatening Masculinity" (2020). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1568. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1568 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Schieß, Bruder: Turkish-German Rap and Threatening Masculinity A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in German Studies from The College of William and Mary by Manasi N. Deorah Accepted for High Honors (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ______________________________________ Prof. Jennifer Gully, Director ________________________________________ Prof. Veronika Burney ______________________________ Prof. Anne Rasmussen Williamsburg, VA May 7, 2020 Deorah 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Part 1: Rap and Cultural -

Champ Lexical De La Religion Dans Les Chansons De Rap Français

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav románských jazyků a literatur Francouzský jazyk a literatura Champ lexical de la religion dans les chansons de rap français Bakalářská diplomová práce Jakub Slavík Vedoucí práce: doc. PhDr. Alena Polická, Ph.D. Brno 2020 2 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou diplomovou práci vypracoval samostatně s využitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. Zároveň prohlašuji, že se elektronická verze shoduje s verzí tištěnou. V Brně dne ………………… ………………………………… Jakub Slavík 3 Nous tenons à remercier Madame Alena Polická, directrice de notre mémoire, à la fois pour ses conseils précieux et pour le temps qu’elle a bien voulu nous consacrer durant l’élaboration de ce mémoire. Par la suite, nous aimerions également remercier chacun qui a contribué de quelque façon à l’accomplissement de notre travail. 4 Table des matières Introduction ......................................................................................................... 6 1. Partie théorique ............................................................................................. 10 1.1. Le lexique religieux : jalons théoriques ................................................................... 10 1.1.1. La notion de champ lexical ..................................................................................... 11 1.1.2. Le lexique de la religion ......................................................................................... 15 1.1.3. L’orthographe du lexique lié à la religion .............................................................. -

The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 122–135 Research Article Adam de Paor-Evans* The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0012 Received January 27, 2018; accepted June 2, 2018 Abstract: In the early 1980s, an important facet of hip hop culture developed a style of music known as electro-rap, much of which carries narratives linked to science fiction, fantasy and references to arcade games and comic books. The aim of this article is to build a critical inquiry into the cultural and socio- political presence of these ideas as drivers for the productions of electro-rap, and subsequently through artists from Newcleus to Strange U seeks to interrogate the value of science fiction from the 1980s to the 2000s, evaluating the validity of science fiction’s place in the future of hip hop. Theoretically underpinned by the emerging theories associated with Afrofuturism and Paul Virilio’s dromosphere and picnolepsy concepts, the article reconsiders time and spatial context as a palimpsest whereby the saturation of digitalisation becomes both accelerator and obstacle and proposes a thirdspace-dromology. In conclusion, the article repositions contemporary hip hop and unearths the realities of science fiction and closes by offering specific directions for both the future within and the future of hip hop culture and its potential impact on future society. Keywords: dromosphere, dromology, Afrofuturism, electro-rap, thirdspace, fantasy, Newcleus, Strange U Introduction During the mid-1970s, the language of New York City’s pioneering hip hop practitioners brought them fame amongst their peers, yet the methods of its musical production brought heavy criticism from established musicians. -

Alan Lomax: Selected Writings 1934-1997

ALAN LOMAX ALAN LOMAX SELECTED WRITINGS 1934–1997 Edited by Ronald D.Cohen With Introductory Essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew L.Kaye ROUTLEDGE NEW YORK • LONDON Published in 2003 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 www.routledge-ny.com Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE www.routledge.co.uk Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” All writings and photographs by Alan Lomax are copyright © 2003 by Alan Lomax estate. The material on “Sources and Permissions” on pp. 350–51 constitutes a continuation of this copyright page. All of the writings by Alan Lomax in this book are reprinted as they originally appeared, without emendation, except for small changes to regularize spelling. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lomax, Alan, 1915–2002 [Selections] Alan Lomax : selected writings, 1934–1997 /edited by Ronald D.Cohen; with introductory essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew Kaye. -

Hip-Hop & the Global Imprint of a Black Cultural Form

Hip-Hop & the Global Imprint of a Black Cultural Form Marcyliena Morgan & Dionne Bennett To me, hip-hop says, “Come as you are.” We are a family. Hip-hop is the voice of this generation. It has become a powerful force. Hip-hop binds all of these people, all of these nationalities, all over the world together. Hip-hop is a family so everybody has got to pitch in. East, west, north or south–we come MARCYLIENA MORGAN is from one coast and that coast was Africa. Professor of African and African –dj Kool Herc American Studies at Harvard Uni- versity. Her publications include Through hip-hop, we are trying to ½nd out who we Language, Discourse and Power in are, what we are. That’s what black people in Amer- African American Culture (2002), ica did. The Real Hiphop: Battling for Knowl- –mc Yan1 edge, Power, and Respect in the LA Underground (2009), and “Hip- hop and Race: Blackness, Lan- It is nearly impossible to travel the world without guage, and Creativity” (with encountering instances of hip-hop music and cul- Dawn-Elissa Fischer), in Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century ture. Hip-hop is the distinctive graf½ti lettering (ed. Hazel Rose Markus and styles that have materialized on walls worldwide. Paula M.L. Moya, 2010). It is the latest dance moves that young people per- form on streets and dirt roads. It is the bass beats DIONNE BENNETT is an Assis- mc tant Professor of African Ameri- and styles of dress at dance clubs. It is local s can Studies at Loyola Marymount on microphones with hands raised and moving to University. -

Abstracts Euromac2014 Eighth European Music Analysis Conference Leuven, 17-20 September 2014

Edited by Pieter Bergé, Klaas Coulembier Kristof Boucquet, Jan Christiaens 2014 Euro Leuven MAC Eighth European Music Analysis Conference 17-20 September 2014 Abstracts EuroMAC2014 Eighth European Music Analysis Conference Leuven, 17-20 September 2014 www.euromac2014.eu EuroMAC2014 Abstracts Edited by Pieter Bergé, Klaas Coulembier, Kristof Boucquet, Jan Christiaens Graphic Design & Layout: Klaas Coulembier Photo front cover: © KU Leuven - Rob Stevens ISBN 978-90-822-61501-6 A Stefanie Acevedo Session 2A A Yale University [email protected] Stefanie Acevedo is PhD student in music theory at Yale University. She received a BM in music composition from the University of Florida, an MM in music theory from Bowling Green State University, and an MA in psychology from the University at Buffalo. Her music theory thesis focused on atonal segmentation. At Buffalo, she worked in the Auditory Perception and Action Lab under Peter Pfordresher, and completed a thesis investigating metrical and motivic interaction in the perception of tonal patterns. Her research interests include musical segmentation and categorization, form, schema theory, and pedagogical applications of cognitive models. A Romantic Turn of Phrase: Listening Beyond 18th-Century Schemata (with Andrew Aziz) The analytical application of schemata to 18th-century music has been widely codified (Meyer, Gjerdingen, Byros), and it has recently been argued by Byros (2009) that a schema-based listening approach is actually a top-down one, as the listener is armed with a script-based toolbox of listening strategies prior to experiencing a composition (gained through previous style exposure). This is in contrast to a plan-based strategy, a bottom-up approach which assumes no a priori schemata toolbox. -

Jovanotti. New York for Life Published on Iitaly.Org (

Jovanotti. New York For Life Published on iItaly.org (http://108.61.128.93) Jovanotti. New York For Life I A (June 25, 2012) A new CD, new concert dates and other surprises for Jovanotti fans. In the upcoming months there are quite a few surprises in store for fans of Jovanotti [2] (AKA Lorenzo Cherubini), a gigantic star of the Italian music scene for the past quarter of a century. Jovanotti is no longer loved exclusively by his Italian fans, over the course of the past few years Jova has conquered the hearts of the American audience, popping up in intimate, small venues such as New York’s The Poisson Rouge [3] or famous music festivals such as San Francisco’s Stern Grove. [4] Page 1 of 3 Jovanotti. New York For Life Published on iItaly.org (http://108.61.128.93) First and foremost on August 7th, ATO Records [5] will release Jovanotti’s new album titled "ITALIA 1988-2012.” The album is a career retrospective but it includes four new tracks and is also the artist's first physical album of studio recordings to be released in the U.S., and the first time much of the material has been released here in any format. The album producer Ian Brennan compiled and remixed what he considers Jovanotti's most compelling material—the songs that exemplify the latter's reputation as a Springsteen-style rock poet and a distinctive singer. Jovanotti laughingly reacted to some of Brennan's choices with, "Are you sure I recorded that song?" The new songs on the CD are: "New York for Life" and "Con La Luce Negli Occhi," and radical re-workings of Jovanotti's songs "La Porta É Aperta" (from the Ora album) and"Mezzogiorno" (from the Safari album). -

“THEY WASN't MAKIN' MY KINDA MUSIC”: HIP-HOP, SCHOOLING, and MUSIC EDUCATION by Adam J. Kruse a DISSERTATION Submitted T

“THEY WASN’T MAKIN’ MY KINDA MUSIC”: HIP-HOP, SCHOOLING, AND MUSIC EDUCATION By Adam J. Kruse A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Music Education—Doctor of Philosophy 2014 ABSTRACT “THEY WASN’T MAKIN’ MY KINDA MUSIC”: HIP-HOP, SCHOOLING, AND MUSIC EDUCATION By Adam J. Kruse With the ambition of informing place consciousness in music education by better understanding the social contexts of hip-hop music education and illuminating potential applications of hip-hop to school music settings, the purpose of this research is to explore the sociocultural aspects of hip-hop musicians’ experiences in music education and music schooling. In particular, this study is informed by the following questions: 1. How do sociocultural contexts (particularly issues of race, space, place, and class) impact hip-hop musicians and their music? 2. What are hip-hop musicians’ perceptions of school and schooling? 3. Where, when, how, and with whom do hip-hop musicians develop and explore their musical skills and understandings? The use of an emergent design in this work allowed for the application of ethnographic techniques within the framework of a multiple case study. One case is an amateur hip-hop musician named Terrence (pseudonym), and the other is myself (previously inexperienced as a hip-hop musician) acting as participant observer. By placing Terrence and myself within our various contexts and exploring these contexts’ influences on our roles as hip-hop musicians, it is possible to understand better who we are, where and when our musical experiences exist(ed), and the complex relationships between our contexts, our experiences, and our perceptions. -

A Te -Jovanotti Chiavi

A TE -JOVANOTTI CHIAVI 4. Ascolta di nuovo la canzone e completa A te che sei l’unica al mondo A te che mi hai insegnato i sogni L’unica ragione per arrivare fino in fondo Ad E l’arte dell’avventura ogni mio respiro A te che credi nel coraggio Quando ti guardo E anche nella paura Dopo un giorno pieno di parole A te che sei la miglior cosa Senza che tu mi dica niente Che mi sia successa Tutto si fa chiaro A te che cambi tutti i giorni A te che mi hai trovato E resti sempre la stessa All’ angolo coi pugni chiusi A te che sei Con le mie spalle contro il muro Semplicemente sei Pronto a difendermi Sostanza dei giorni miei Con gli occhi bassi Sostanza dei sogni miei Stavo in fila A te che sei Con i disillusi Essenzialmente sei Tu mi hai raccolto come un gatto Sostanza dei sogni miei E mi hai portato con te Sostanza dei giorni miei A te io canto una canzone A te che non ti piaci mai Perché non ho altro E sei una meraviglia Niente di meglio da offrirti Le forze della natura si concentrano in te Di tutto quello che ho Che sei una roccia sei una pianta sei un uragano Prendi il mio tempo Sei l’orizzonte che mi accoglie quando mi allontano E la magia A te che sei l’unica amica Che con un solo salto Che io posso avere Ci fa volare dentro all’aria L’unico amore che vorrei Come bollicine Se io non ti avessi con me A te che sei a te che hai reso la mia vita bella da morire, Semplicemente sei che riesci a render la fatica un immenso piacere, Sostanza dei giorni miei a te che sei il mio grande amore Sostanza dei giorni miei ed il mio amore grande, A te che sei il mio grande amore a te che hai preso la mia vita Ed il mio amore grande e ne hai fatto molto di più, A te che hai preso la mia vita a te che hai dato senso al tempo senza misurarlo, E ne hai fatto molto di più a te che sei il mio amore grande A te che hai dato senso al tempo ed il mio grande amore, Senza misurarlo a te che sei, A te che sei il mio amore grande semplicemente sei, Ed il mio grande amore sostanza dei giorni miei, A te che io sostanza dei sogni miei..