Www .P Re S Tig Ec O Llec Tib Le S .Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

ZEN-NOH Report 2019 We, the ZEN-NOH Group, Are the Trusted and Reliable Go-Between Linking Producers and Consumers

The Wengfu & Zijin Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. ammonium phosphate plant/Shanghang, China ZEN-NOH Report A farm engaging in contracted cultivation of rice/Saitama Prefecture A yakiniku restaurant operated directly by JA ZEN- A truck delivering gasoline and other NOH Meat Foods Co., Ltd. products to JA-SS service stations Yakiniku Honpo Pure Kitasenju Marui/Tokyo Angele, a mini tomato for which ZEN-NOH is the sole seed supplier TAMAGO COCCO, a sweets shop operated directly by JA ZEN-NOH Tamago Co., Ltd./Tokyo The Southern Prefecture VF Station, which packages strawberries/Fukuoka Prefecture JA Farmers Tomioka, which includes a direct-sales shop for domestic farm products/Gunma Prefecture ZEN-NOH Grain Corporation’s grain export facility with expanded loading capacity/New Orleans, La., U.S.A. National Federation of Agricultural Cooperative Associations JA is the abbreviation for Japan Agricultural Cooperatives. 1-3-1 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-6832 Tel: +81-3-6271-8055 Fax: +81-3-5218-2506 Website: www.zennoh.or.jp Published in September 2019 ZEN-NOH Group Corporate Identity ZEN-NOH Report 2019 We, the ZEN-NOH Group, are the trusted and reliable go-between linking producers and consumers. 4 Message from ZEN-NOH Representatives We think about peace of mind from three points of view: Three-Year 6 Changing business environment ・Efforts to support farm management and lifestyles, and to create vibrant production centers Business Plan 8 ZEN-NOH's courses of action for the next 5-10 years Delivering to consumers domestically-produced fresh and safe agriculture and livestock products ・ (FY2019-2021) ・Proactive efforts to protect the earth's environment 10 Top-priority measures 12 ZEN-NOH as a cooperative JA Manifesto 15 We, members, employees and officers of JA, act in accord with the fundamental definitions, values and principles of cooperative union The SDGs and co-operative initiatives activities (independence, self-reliance, participation, democratic management, fairness, and solidarity). -

Many Paths Lead Walk-Ons to BU

Missing perspectives of history are given a voice At a symposium Tuesday, scholars addressed the stories of history from the eyes of women see Arts, page 5 baylorlariat com The Baylor Lariat WE’RE THERE WHEN YOU CAN’T BE From Business, page 3: A student economist weighs the pros and cons of students debt. Is it worth it? Wednesday | March 18, 2015 America, Cuba wrap up meetings By Michael Weissenstein Associated Press HAVANA — A third round of ne- gotiations over the restoration of full diplomatic relations ended after a day of talks, Cuban and U.S. officials said Tuesday. Hours later, Cuban Presi- dent Raul Castro delivered a toughly worded attack on the United States for levying a new round of sanctions on his country’s closest ally, Venezu- ela. KEVIN FREEMAN | LARIAT PHOTOGRAPHER Neither Cuba nor the U.S. pro- vided details on whether progress Pinch a bite to eat on St. Paddy’s Day was made toward a deal on reopen- The unique Baylor tradition of Dr Pepper Hour received a makeover in honor of St. Patrick’s Day on Tuesday. Green Dr Pepper floats were served at Robinson Tower, at Dr Pepper ing embassies in Washington and Hour in the Bill Daniels Student Union Center and at the softball game pictured here against the University of Houston at Getterman Stadium. Havana. The two countries have been try- ing to strike an agreement on embas- sies before presidents Barack Obama and Raul Castro attend the Summit of the Americas in Panama on April 10-11. Many paths lead walk-ons to BU Cuba’s Ministry of Foreign Rela- tions said the talks took place “in a By Shehan Jeyarajah also transferred out before ever Mills loves basketball. -

News Pdf 311.Pdf

2013 World Baseball Classic- The Nominated Players of Team Japan(Dec.3,2012) *ICC-Intercontinental Cup,BWC-World Cup,BAC-Asian Championship Year&Status( A-Amateur,P-Professional) *CL-NPB Central League,PL-NPB Pacific League World(IBAF,Olympic,WBC) Asia(BFA,Asian Games) Other(FISU.Haarlem) 12 Pos. Name Team Alma mater in Amateur Baseball TB D.O.B Asian Note Haarlem 18U ICC BWC Olympic WBC 18U BAC Games FISU CUB- JPN P 杉内 俊哉 Toshiya Sugiuchi Yomiuri Giants JABA Mitsubishi H.I. Nagasaki LL 1980.10.30 00A,08P 06P,09P 98A 01A 12 Most SO in CL P 内海 哲也 Tetsuya Utsumi Yomiuri Giants JABA Tokyo Gas LL 1982.4.29 02A 09P 12 Most Win in CL P 山口 鉄也 Tetsuya Yamaguchi Yomiuri Giants JHBF Yokohama Commercial H.S LL 1983.11.11 09P ○ 12 Best Holder in CL P 澤村 拓一 Takuichi Sawamura Yomiuri Giants JUBF Chuo University RR 1988.4.3 10A ○ P 山井 大介 Daisuke Yamai Chunichi Dragons JABA Kawai Musical Instruments RR 1978.5.10 P 吉見 一起 Kazuki Yoshimi Chunichi Dragons JABA TOYOTA RR 1984.9.19 P 浅尾 拓也 Takuya Asao Chunichi Dragons JUBF Nihon Fukushi Univ. RR 1984.10.22 P 前田 健太 Kenta Maeda Hiroshima Toyo Carp JHBF PL Gakuen High School RR 1988.4.11 12 Best ERA in CL P 今村 猛 Takeshi Imamura Hiroshima Toyo Carp JHBF Seihou High School RR 1991.4.17 ○ P 能見 篤史 Atsushi Nomi Hanshin Tigers JABA Osaka Gas LL 1979.5.28 04A 12 Most SO in CL P 牧田 和久 Kazuhisa Makita Seibu Lions JABA Nippon Express RR 1984.11.10 P 涌井 秀章 Hideaki Wakui Seibu Lions JHBF Yokohama High School RR 1986.6.21 04A 08P 09P 07P ○ P 攝津 正 Tadashi Settu Fukuoka Softbank Hawks JABA Japan Railway East-Sendai RR 1982.6.1 07A 07BWC Best RHP,12 NPB Pitcher of the Year,Most Win in PL P 大隣 憲司 Kenji Otonari Fukuoka Softbank Hawks JUBF Kinki University LL 1984.11.19 06A ○ P 森福 允彦 Mitsuhiko Morifuku Fukuoka Softbank Hawks JABA Shidax LL 1986.7.29 06A 06A ○ P 田中 将大 Masahiro Tanaka Tohoku Rakuten Golden Eagles JHBF Tomakomai H.S.of Komazawa Univ. -

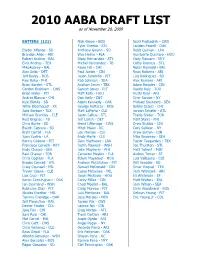

2010 AABA DRAFT LIST As of November 20, 2009

2010 AABA DRAFT LIST as of November 20, 2009 BATTERS (131) Nick Green - BOS Scott Podsednik - CWS Tyler Greene - STL Landon Powell - OAK Eliezer Alfonzo - SD Anthony Gwynn - SD Robb Quinlan - LAA Brandon Allen - ARI Wes Helms - FLA Humberto Quintero - HOU Robert Andino - BAL Diory Hernandez - ATL Cody Ransom - NYY Elvis Andrus - TEX Michel Hernandez - TB Colby Rasmus - STL MikeAubrey - BAL Koyie Hill - CHI Nolan Reimold - BAL Alex Avila - DET Paul Janish - CIN Ryan Roberts - ARI Jeff Bailey - BOS Jason Jaramillo - PIT Luis Rodriguez - SD Paul Bako - PHI Rob Johnson - SEA Alex Romero - ARI Brian Barden - STL Andruw Jones - TEX Adam Rosales - CIN Gordon Beckham - CWS Garrett Jones - PIT Randy Ruiz - TOR Brian Bixler - PIT Matt Kata - HOU Rusty Ryal - ARI Andres Blanco - CHI Don Kelly - DET Omir Santos - NY Kyle Blanks - SD Adam Kennedy - OAK Michael Saunders - SEA Willie Bloomquist - KC George Kottaras - BOS Bobby Scales - CHI Julio Borbon - TEX Matt LaPorta - CLE Jordan Schafer - ATL Michael Brantley - CLE Jason LaRue - STL Travis Snider - TOR Reid Brignac - TB Jeff Larish - DET Matt Stairs - PHI Chris Burke - SD Brent Lillibridge - CWS Drew Stubbs - CIN Everth Cabrera - SD Mitch Maier - KC Cory Sullivan - NY Brett Carroll - FLA Lou Marson - CLE Drew Sutton - CIN Juan Castro - LA Andy Marte - CLE Mike Sweeney - SEA Ronny Cedeno - PIT Gary Matthews - LAA Taylor Teagarden - TEX Francisco Cervelli - NYY Justin Maxwell - WSH Joe Thurston - STL Endy Chavez - SEA John Mayberry - PHI Matt Tolbert - MIN Raul Chavez - TOR Cameron Maybin - FLA Andres -

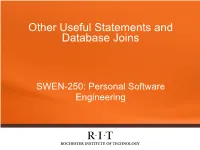

Other Useful Statements and Database Joins

Other Useful Statements and Database Joins SWEN-250: Personal Software Engineering Overview • Other Useful Statements: • Database Info: • SELECT Functions • .tables • SELECT Like • .schema • ORDER BY • LIMIT • Joins: • UPDATE • LEFT JOIN • DELETE • RIGHT JOIN • ALTER TABLE • INNER JOIN • DROP TABLE • FULL OUTER JOIN SWEN-250 Personal Software Engineering Other Useful Statements SWEN-250 Personal Software Engineering SELECT Functions SELECT AVG(grade) FROM students; SELECT SUM(grade) FROM students; SELECT MIN(grade) FROM students; SELECT MAX(grade) FROM students; SELECT count(id) FROM students; There are various functions that you can apply to the values returned from a select statement (many more on the reference pages). sqlite> select COUNT(*) FROM Player; COUNT(*) 125 sqlite> select SUM(age) FROM Player; SUM(age) 3560 sqlite> select AVG(age) FROM Player; AVG(age) 28.48 sqlite> select MIN(age) FROM Player; MIN(age) 20 sqlite> select MAX(AGE) FROM Player; SWEN-250 Personal Software Engineering SELECT Like SELECT * FROM Player WHERE name LIKE "K%"; You can use like to do partial string matching. The '%;' character acts like a wild card. The above will select all players whose name begins with K. sqlite> SELECT * FROM Player WHERE name LIKE "K%"; name|position|number|team|age Koji Uehara|1|19|Red Sox|40 Kevin Gausman|1|39|Orioles|24 Kevin Pillar|7|11|Blue Jays|26 Kevin Jepsen|1|40|Rays|30 SWEN-250 Personal Software Engineering ORDER BY SELECT * FROM Player ORDER BY name; Putting 'ORDER BY' at the end of a select statement will sort the output by the column name. There is also a 'REVERSE ORDER BY' which does the opposite sorted order (note that it looks like this is not working in sqlite3). -

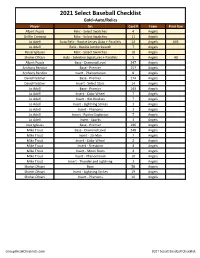

2021 Panini Select Baseball Checklist

2021 Select Baseball Checklist Gold=Auto/Relics Player Set Card # Team Print Run Albert Pujols Relic - Select Swatches 4 Angels Griffin Canning Relic - Select Swatches 11 Angels Jo Adell Auto Relic - Rookie Jersey Auto + Parallels 14 Angels 645 Jo Adell Relic - Rookie Jumbo Swatch 7 Angels Raisel Iglesias Relic - Select Swatches 18 Angels Shohei Ohtani Auto - Selective Signatures + Parallels 5 Angels 40 Albert Pujols Base - Diamond Level 247 Angels Anthony Rendon Base - Premier 157 Angels Anthony Rendon Insert - Phenomenon 8 Angels David Fletcher Base - Premier 174 Angels David Fletcher Insert - Select Stars 14 Angels Jo Adell Base - Premier 143 Angels Jo Adell Insert - Color Wheel 7 Angels Jo Adell Insert - Hot Rookies 7 Angels Jo Adell Insert - Lightning Strikes 1 Angels Jo Adell Insert - Phenoms 3 Angels Jo Adell Insert - Rookie Explosion 7 Angels Jo Adell Insert - Sparks 1 Angels Jose Iglesias Base - Premier 196 Angels Mike Trout Base - Diamond Level 248 Angels Mike Trout Insert - 25-Man 7 Angels Mike Trout Insert - Color Wheel 2 Angels Mike Trout Insert - Firestorm 4 Angels Mike Trout Insert - Moon Shots 4 Angels Mike Trout Insert - Phenomenon 10 Angels Mike Trout Insert - Thunder and Lightning 3 Angels Shohei Ohtani Base 58 Angels Shohei Ohtani Insert - Lightning Strikes 19 Angels Shohei Ohtani Insert - Phenoms 10 Angels GroupBreakChecklists.com 2021 Select Baseball Checklist Player Set Card # Team Print Run Abraham Toro Relic - Select Swatches 1 Astros Alex Bregman Auto - Moon Shot Signatures + Parallels 2 Astros 102 Bryan Abreu -

Sports Quiz When Were the First Tokyo Olympic Games Held?

Sports Quiz When were the first Tokyo Olympic Games held? ① 1956 ② 1964 ③ 1972 ④ 1988 When were the first Tokyo Olympic Games held? ① 1956 ② 1964 ③ 1972 ④ 1988 What is the city in which the Winter Olympic Games were held in 1998? ① Nagano ② Sapporo ③ Iwate ④ Niigata What is the city in which the Winter Olympic Games were held in 1998? ① Nagano ② Sapporo ③ Iwate ④ Niigata Where do sumo wrestlers have their matches? ① sunaba ② dodai ③ doma ④ dohyō Where do sumo wrestlers have their matches? ① sunaba ② dodai ③ doma ④ dohyō What do sumo wrestlers sprinkle before a match? ① salt ② soil ③ sand ④ sugar What do sumo wrestlers sprinkle before a match? ① salt ② soil ③ sand ④ sugar What is the action wrestlers take before a match? ① shiko ② ashiage ③ kusshin ④ tsuppari What is the action wrestlers take before a match? ① shiko ② ashiage ③ kusshin ④ tsuppari What do wrestlers wear for a match? ① dōgi ② obi ③ mawashi ④ hakama What do wrestlers wear for a match? ① dōgi ② obi ③ mawashi ④ hakama What is the second highest ranking in sumo following yokozuna? ① sekiwake ② ōzeki ③ komusubi ④ jonidan What is the second highest ranking in sumo following yokozuna? ① sekiwake ② ōzeki ③ komusubi ④ jonidan On what do judo wrestlers have matches? ① sand ② board ③ tatami ④ mat On what do judo wrestlers have matches? ① sand ② board ③ tatami ④ mat What is the decision of the match in judo called? ① ippon ② koka ③ yuko ④ waza-ari What is the decision of the match in judo called? ① ippon ② koka ③ yuko ④ waza-ari Which of these is not included in the waza techniques of -

List of Players in Apba's 2018 Base Baseball Card

Sheet1 LIST OF PLAYERS IN APBA'S 2018 BASE BASEBALL CARD SET ARIZONA ATLANTA CHICAGO CUBS CINCINNATI David Peralta Ronald Acuna Ben Zobrist Scott Schebler Eduardo Escobar Ozzie Albies Javier Baez Jose Peraza Jarrod Dyson Freddie Freeman Kris Bryant Joey Votto Paul Goldschmidt Nick Markakis Anthony Rizzo Scooter Gennett A.J. Pollock Kurt Suzuki Willson Contreras Eugenio Suarez Jake Lamb Tyler Flowers Kyle Schwarber Jesse Winker Steven Souza Ender Inciarte Ian Happ Phillip Ervin Jon Jay Johan Camargo Addison Russell Tucker Barnhart Chris Owings Charlie Culberson Daniel Murphy Billy Hamilton Ketel Marte Dansby Swanson Albert Almora Curt Casali Nick Ahmed Rene Rivera Jason Heyward Alex Blandino Alex Avila Lucas Duda Victor Caratini Brandon Dixon John Ryan Murphy Ryan Flaherty David Bote Dilson Herrera Jeff Mathis Adam Duvall Tommy La Stella Mason Williams Daniel Descalso Preston Tucker Kyle Hendricks Luis Castillo Zack Greinke Michael Foltynewicz Cole Hamels Matt Harvey Patrick Corbin Kevin Gausman Jon Lester Sal Romano Zack Godley Julio Teheran Jose Quintana Tyler Mahle Robbie Ray Sean Newcomb Tyler Chatwood Anthony DeSclafani Clay Buchholz Anibal Sanchez Mike Montgomery Homer Bailey Matt Koch Brandon McCarthy Jaime Garcia Jared Hughes Brad Ziegler Daniel Winkler Steve Cishek Raisel Iglesias Andrew Chafin Brad Brach Justin Wilson Amir Garrett Archie Bradley A.J. Minter Brandon Kintzler Wandy Peralta Yoshihisa Hirano Sam Freeman Jesse Chavez David Hernandez Jake Diekman Jesse Biddle Pedro Strop Michael Lorenzen Brad Boxberger Shane Carle Jorge de la Rosa Austin Brice T.J. McFarland Jonny Venters Carl Edwards Jackson Stephens Fernando Salas Arodys Vizcaino Brian Duensing Matt Wisler Matt Andriese Peter Moylan Brandon Morrow Cody Reed Page 1 Sheet1 COLORADO LOS ANGELES MIAMI MILWAUKEE Charlie Blackmon Chris Taylor Derek Dietrich Lorenzo Cain D.J. -

Baseball in Japan and the US History, Culture, and Future Prospects by Daniel A

Sports, Culture, and Asia Baseball in Japan and the US History, Culture, and Future Prospects By Daniel A. Métraux A 1927 photo of Kenichi Zenimura, the father of Japanese-American baseball, standing between Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth. Source: Japanese BallPlayers.com at http://tinyurl.com/zzydv3v. he essay that follows, with a primary focus on professional baseball, is intended as an in- troductory comparative overview of a game long played in the US and Japan. I hope it will provide readers with some context to learn more about a complex, evolving, and, most of all, Tfascinating topic, especially for lovers of baseball on both sides of the Pacific. Baseball, although seriously challenged by the popularity of other sports, has traditionally been considered America’s pastime and was for a long time the nation’s most popular sport. The game is an original American sport, but has sunk deep roots into other regions, including Latin America and East Asia. Baseball was introduced to Japan in the late nineteenth century and became the national sport there during the early post-World War II period. The game as it is played and organized in both countries, however, is considerably different. The basic rules are mostly the same, but cultural differences between Americans and Japanese are clearly reflected in how both nations approach their versions of baseball. Although players from both countries have flourished in both American and Japanese leagues, at times the cultural differences are substantial, and some attempts to bridge the gaps have ended in failure. Still, while doubtful the Japanese version has changed the American game, there is some evidence that the American version has exerted some changes in the Japanese game. -

Globalization, Sports Law and Labour Mobility: the Case of Professional

MATT NICHOL Globalization, Sports Law and Labour Mobility: The Case of Professional Baseball in the United States and Japan Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA 2019, vii + 245 pp. (203 pp. + Bibliography & Index), ca. 125 US$, ISBN: 978-1-78811-500-1 Before the Covid-19 pandemic ruined everything, the biggest news in Major League Baseball (“MLB”) leading up to the 2020 season was the trade of one of the world’s best players, Mookie BETTS, from the Boston Red Sox to the Los Angeles Dodgers. The trade negotiations were marked by uncertainty, reversals by team executives, and rumours, prompting Tony CLARK, the Executive Director of the MLB players’ union, to state that “The unethical leaking of medical information as well as the perversion of the salary arbitration process serve as continued reminders that too often Players are treated as commodities by those running the game.”1 The confronting assertion that baseball labour is commodified (when the humanity of even our heroes is denied, what hope have the rest of us?) has not been weakened by the MLB’s efforts to restart the season during the pandemic, making Matt NICHOL’s schoolarly examination of “labour regulation and labour mobility in professional baseball’s two elite leagues” (p. 1) both timely and important. Combining theoretical and black letter approaches, NICHOL’s book dis- cusses the two premier professional baseball leagues in the world (MLB in the United States and Canada and Nippon Professional Baseball (“NPB”) in Japan) – their internal and external rules and regulations, their collective and individual labour agreements with players, and their institutional actors (league structures, player unions, agents, etc.) – by way of a critical analysis of labour mobility, not just in professional baseball, but in global labour markets more generally.