Western Legal History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Mourns Passing of Judge Pamela Ann Rymer

N E W S R E L E A S E September 22, 2011 Contact: David Madden (415) 355-8800 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Mourns Passing of Judge Pamela Ann Rymer SAN FRANCISCO – The Hon. Pamela Ann Rymer, a distinguished judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, died Wednesday, September 21, 2011, after a long illness. She was 69. Judge Rymer was diagnosed with cancer in 2009 and had been in failing health in recent months. She passed with friends at her bedside. “Judge Rymer maintained her calendar throughout her illness,” observed Ninth Circuit Chief Judge Alex Kozinski. “Her passion for the law and dedication to the work of the court was inspiring. She will be sorely missed by all of her colleagues.” Judge Rymer served on the federal bench at both the appellate and trial levels for more than 28 years. Nominated by President Reagan, she was appointed a judge of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California on February 24, 1983. She was elevated to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals by President George H.W. Bush, receiving her commission on May 22, 1989. During her 22 years on the appellate court, Judge Rymer sat on more than 800 merits panels and authored 335 panel opinions. She last heard oral arguments in July and her most recent opinion was filed in August. Her productivity was remarkable and every case received her full attention, colleagues said. "Each case was intrinsically important to her. Finding the right answer for the parties and doing the law correctly were foremost in her mind in every matter. -

William Alsup

William Alsup An Oral History Conducted by Leah McGarrigle 2016-2017 William Alsup An Oral History Conducted by Leah McGarrigle 2016-2017 Copyright © 2021 William Alsup, Leah McGarrigle All rights reserved. Copyright in the manuscript and recording is owned by William Alsup and Leah McGarrigle, who have made the materials available under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC 4.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows: "William Alsup: An Oral History Conducted by Leah McGarrigle, 2016-2017”. Transcription by Christine Sinnott Book design by Anna McGarrigle Judge William Alsup was born in Mississippi in 1945 and lived there until he left for Harvard Law School in 1967. At Harvard, he earned a law degree plus a master’s degree in public policy from the Kennedy School of Government. In 1971–72, he clerked for Justice William O. Douglas of the United States Supreme Court and worked with him on the Abortion Cases and the “Trees Have Standing” case, among others. Alsup and his young family then returned to Mississippi, where he practiced civil rights law, went broke, and eventually relocated to San Francisco. There he be- came a trial lawyer, a practice interrupted by two years of appel- late practice as an Assistant to the Solicitor General in the United States Department of Justice (from 1978–80). In 1999, President Bill Clinton nominated him and the Senate conirmed him as a United States District Judge in San Francisco. He took the oath of oice on August 17, 1999, and serves still on active status. -

Files Folder Title:Counsel's Office January 1984- June 1984 (5) Box: 7

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Baker, James A.: Files Folder Title: Counsel’s Office January 1984- June 1984 (5) Box: 7 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ ' ·.: ,· ·· . -·· -.. -·: • . ...: . : . > "~ .. .. • .: . .. ... DEANE C. DAVIS 5 OYER AVENUE MONTPEt.IER, VERMONT 05602 December 20, 1983 The President The White House Washington, D.C. 20500 ~De-ar- : :Mr. President:. · This letter is in reference to the forthcoming vacancy ... ·. in the office of. Federal. District Judge for Vermont, occasioned by the retirement of Judge James Holden. Senator Stafford tells me that he is to recommend several. names including that of Lawrence A. Wright of. _Hines .burg._.:. -. I strongly endorse Mr. Wright. Mr. Wright is highly qualified for this posi~ion on all counts: ability, age, judici~l temperament and trial experience. When I was Governor of Vermont I selected Mr. Wright for appointment to the office of Vermont Tax Commissioner. The Legislature had just passed a new and highly complicated Sales Tax and a highly qualified man was needed to set up and administer the new system. He performed in a superb manner. His· extensive experience with the Internal Revenue Servic e as a trial attorney eminently qualifies him to become a judge. He is fully at home in the court room. -

The History, Content, Application and Influence of the Northern District of California’S Patent Local Rules

THE HISTORY, CONTENT, APPLICATION AND INFLUENCE OF THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA’S PATENT LOCAL RULES James Ware† & Brian Davy†† Abstract On December 1, 2000, the United States District Court for the Northern District of California became the first district court to promulgate rules governing the content and timing of disclosures in patent-related cases. The Northern District’s conception of Patent Local Rules finds its origins in the concerns during the 1980’s and 1990’s, when the increasing cost and expense of civil litigation came under increasing attack from commentators and all three branches of the federal government. Despite efforts to improve the efficiency of civil litigation generally, patent litigation proved particularly burdensome on litigants and the courts. The Supreme Court’s decision in Markman v. Westview Instruments, Inc. only exacerbated this situation. The Northern District’s Patent Local Rules are specifically tailored to address the unique challenges that arise during patent litigation, particularly during the pretrial discovery process. The Rules require the patentee and the accused infringer to set forth detailed infringement and invalidity theories early in the case. The Rules also govern the content and timing of disclosures related to the claim construction hearing, an event unique to patent litigation that is often case-dispositive. The Northern District’s Patent Local Rules have been expressly endorsed by the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. The Rules have also proven highly influential in other judicial districts, as evidenced by the adoption of substantially similar rules in a growing number of district courts. Substantive differences do exist, however, between the patent local rules of various district courts. -

Settlement Agreement Is Entered Into by Plaintiffs on Behalf of Themselves and 3 the Class Members, and Defendant Reckitt Benckiser, LLC

Case 3:17-cv-03529-VC Document 221-2 Filed 05/12/21 Page 2 of 141 1 BLOOD HURST & O’REARDON, LLP TIMOTHY G. BLOOD (149343) 2 THOMAS J. O’REARDON II (247952) 501 West Broadway, Suite 1490 3 San Diego, CA 92101 Tel: 619/338-1100 4 619/338-1101 (fax) [email protected] 5 [email protected] 6 Class Counsel 7 [Additional Counsel Appear on Signature Page] 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA – SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 10 GORDON NOBORU YAMAGATA and Case No. 3:17-cv-03529-VC STAMATIS F. PELARDIS, individually and 11 on behalf of all others similarly situated, STIPULATION OF SETTLEMENT 12 Plaintiffs, LLP CLASS ACTION , 13 v. 14 RECKITT BENCKISER LLC, District Judge Vince Chhabria EARDON Courtroom 4, 17th Floor 15 Defendant. O’ R Complaint Filed: June 19, 2017 & 16 Trial Date: N/A URST 17 H 18 LOOD LOOD B 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Case No. 3:17-cv-03529-VC 00177902 STIPULATION OF SETTLEMENT Case 3:17-cv-03529-VC Document 221-2 Filed 05/12/21 Page 3 of 141 1 TABLE OF EXHIBITS 2 Document Exhibit Number 3 Preliminary Approval Order ................................................................................................. 1 4 Final Approval Order ............................................................................................................ 2 5 Final Judgment ..................................................................................................................... 3 6 Class Notice Program ........................................................................................................... -

09FB Guide P163-202 Color.Indd

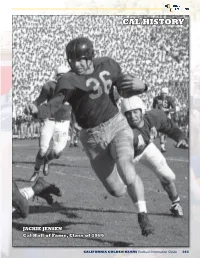

CCALAL HHISTORYISTORY JJACKIEACKIE JJENSENENSEN CCalal HHallall ooff FFame,ame, CClasslass ooff 11986986 CALIFORNIA GOLDEN BEARS FootballFtbllIf Information tiGid Guide 163163 HISTORY OF CAL FOOTBALL, YEAR-BY-YEAR YEAR –––––OVERALL––––– W L T PF PA COACH COACHING SUMMARY 1886 6 2 1 88 35 O.S. Howard COACH (YEARS) W L T PCT 1887 4 0 0 66 12 None O.S. Howard (1886) 6 2 1 .722 1888 6 1 0 104 10 Thomas McClung (1892) 2 1 1 .625 1890 4 0 0 45 4 W.W. Heffelfi nger (1893) 5 1 1 .786 1891 0 1 0 0 36 Charles Gill (1894) 0 1 2 .333 1892 Sp 4 2 0 82 24 Frank Butterworth (1895-96) 9 3 3 .700 1892 Fa 2 1 1 44 34 Thomas McClung Charles Nott (1897) 0 3 2 .200 1893 5 1 1 110 60 W.W. Heffelfi nger Garrett Cochran (1898-99) 15 1 3 .868 1894 0 1 2 12 18 Charles Gill Addison Kelly (1900) 4 2 1 .643 Nibs Price 1895 3 1 1 46 10 Frank Butterworth Frank Simpson (1901) 9 0 1 .950 1896 6 2 2 150 56 James Whipple (1902-03) 14 1 2 .882 1897 0 3 2 8 58 Charles P. Nott James Hooper (1904) 6 1 1 .813 1898 8 0 2 221 5 Garrett Cochran J.W. Knibbs (1905) 4 1 2 .714 1899 7 1 1 142 2 Oscar Taylor (1906-08) 13 10 1 .563 1900 4 2 1 53 7 Addison Kelly James Schaeffer (1909-15) 73 16 8 .794 1901 9 0 1 106 15 Frank Simpson Andy Smith (1916-25) 74 16 7 .799 1902 8 0 0 168 12 James Whipple Nibs Price (1926-30) 27 17 3 .606 1903 6 1 2 128 12 Bill Ingram (1931-34) 27 14 4 .644 1904 6 1 1 75 24 James Hopper Stub Allison (1935-44) 58 42 2 .578 1905 4 1 2 75 12 J.W. -

Academic CV Examples

SAMPLE CV JOAN ARC The University of Chicago Law School 1111 60th St. • Chicago, IL 60637 (773) 834-4444 • [email protected] EDUCATION YALE LAW SCHOOL • New Haven, CT • J.D., 2018 • Yale Law Journal, Articles Editor • Yale Journal of International Law, Articles Editor • ACLU Immigrants’ Rights Project • Immigration Clinic GOUCHER COLLEGE • Baltimore, MD • B.A. in International Relations, with honors, 2016 • Honors: Phi Beta Kappa, Phi Beta Kappa Award for Outstanding Paper, Dean’s Scholarship, Munce Scholarship for International Relations, Class of 1906 Fellowship, German Embassy Language Award • Amnesty International Goucher Group, Co-President • Research Assistant, Professor Jane Bennett, Political Theory • Senior Thesis: Dilemmas of Transitional Justice and the Indeterminacy of Law: The Trial of the Former Bulgarian Communist Leader, Todor Zhivkov CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY • Cambridge, UK • Kaplan Scholar, 2018-2009 TEACHING AND RESEARCH INTERESTS • Primary interests: International Law, International Criminal Law, Comparative Law, Comparative Criminal Law, Criminal Law, Criminal Procedure • Additional interests: Civil Procedure, Evidence, International Commercial Arbitration, International Organizations, Immigration Law, Human Rights Law, Criminal Justice PUBLICATIONS AND WORKS IN PROGRESS • Jury Sentencing as Democratic Practice, 89 VA. L. REV. 311 (2018), cited in Wright & Miller, 3 Fed. Prac. & Proc. Crim.2d 526 (West Supp. 2018) • Case Note, Sovereignty on Our Terms, 110 YALE L.J. 885 (2017), cited in In re Vitamins Litigation, No. 99-1978FH, 2005 WL 1049433 (D.D.C. June 20, 2017) • Book Review, 26 YALE J. INT’L L. 529 (2012) (reviewing WILLIAM SCHABAS, GENOCIDE IN INTERNATIONAL LAW (2013)) • Update of Current Legal Proceedings at the ICTY, 13 LEIDEN J. INT’L L. -

Lawyer NEW DEAN TAKES CHARGE

Stanford FALL 2004 FALL Lawyer NEW DEAN TAKES CHARGE Larry D. Kramer brings fresh ideas, lots of energy, and a willingness to stir things up a bit. Remember Stanford... F rom his family’s apricot orchard in Los Altos Hills, young Thomas Hawley could see Hoover Tower and hear the cheers in Stanford Stadium. “In those days my heroes were John Brodie and Chuck Taylor,” he says, “and my most prized possessions were Big Game programs.” Thomas transferred from Wesleyan University to Stanford as a junior in and two years later enrolled in the Law School, where he met John Kaplan. “I took every course Professor Kaplan taught,” says Thomas. “He was a brilliant, often outrageous teacher, who employed humor in an attempt to drive the law into our not always receptive minds.” In choosing law, Thomas followed in the footsteps of his father, Melvin Hawley (L.L.B. ’), and both grandfathers. “I would have preferred to be a professional quarterback or an opera singer,” he says (he fell in love with opera while at Stanford-in-Italy), “and I might well have done so but for a complete lack of talent.” An estate planning attorney on the Monterey Peninsula, Thomas has advised hundreds of families how to make tax-wise decisions concerning the distribution of their estates. When he decided the time had come to sell his rustic Carmel cottage, he took his own advice and put the property in a charitable remainder trust instead, avoiding the capital gains tax he otherwise would have paid upon sale. When the trust terminates, one-half of it will go to Stanford Law School. -

The Washington State Census Board and Its Demographic Legacy

SPRINGER BRIEFS IN POPULATION STUDIES David A. Swanson The Washington State Census Board and Its Demographic Legacy 123 SpringerBriefs in Population Studies More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/10047 David A. Swanson The Washington State Census Board and Its Demographic Legacy 123 David A. Swanson Department of Sociology University of California Riverside USA ISSN 2211-3215 ISSN 2211-3223 (electronic) SpringerBriefs in Population Studies ISBN 978-3-319-25947-5 ISBN 978-3-319-25948-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-25948-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015954599 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Nominations Submitted to The

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Nominations Submitted to the Senate November 21, 2014 The following list does not include promotions of members of the Uniformed Services, nominations to the Service Academies, or nominations of Foreign Service Officers. Submitted January 6 Jill A. Pryor, of Georgia, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 11th Circuit, vice Stanley F. Birch, Jr., retired. Carolyn B. McHugh, of Utah, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 10th Circuit, vice Michael R. Murphy, retired. Michelle T. Friedland, of California, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the Ninth Circuit, vice Raymond C. Fisher, retired. Nancy L. Moritz, of Kansas, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 10th Circuit, vice Deanell Reece Tacha, retired. John B. Owens, of California, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the Ninth Circuit, vice Stephen S. Trott, retired. David Jeremiah Barron, of Massachusetts, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the First Circuit, vice Michael Boudin, retired. Robin S. Rosenbaum, of Florida, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 11th Circuit, vice Rosemary Barkett, resigned. Julie E. Carnes, of Georgia, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 11th Circuit, vice James Larry Edmondson, retired. Gregg Jeffrey Costa, of Texas, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the Fifth Circuit, vice Fortunato P. Benavides, retired. Rosemary Márquez, of Arizona, to be U.S. District Judge for the District of Arizona, vice Frank R. Zapata, retired. Pamela L. Reeves, of Tennessee, to be U.S. District Judge for the Eastern District of Tennessee, vice Thomas W. Phillips, retiring. -

(“ERISA”) Decisions As They Were Reported on Westlaw Between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2016

DRAFT * This document is a case summary compilation of select Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (“ERISA”) decisions as they were reported on Westlaw between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2016. Nothing in this document constitutes legal advice. Case summaries prepared by Michelle L. Roberts, Partner, Roberts Bartolic LLP, 1050 Marina Village Parkway, Suite 105, Alameda, CA 94501. © Roberts Bartolic LLP I. Attorneys’ Fees .................................................................................................................. 11 A. First Circuit ..................................................................................................................................... 11 B. Second Circuit ................................................................................................................................. 11 C. Third Circuit .................................................................................................................................... 14 D. Fourth Circuit .................................................................................................................................. 14 E. Fifth Circuit ..................................................................................................................................... 15 F. Sixth Circuit .................................................................................................................................... 16 G. Seventh Circuit ............................................................................................................................... -

Empirical Research and the Politics of Judicial Administration: Creating the Federal Judicial Center

EMPIRICAL RESEARCH AND THE POLITICS OF JUDICIAL ADMINISTRATION: CREATING THE FEDERAL JUDICIAL CENTER RUSSELL WHEELER* I INTRODUCTION Throughout the twentieth century, a vocal minority of law teachers, social scientists, judges, and lawyers have produced legal procedure scholarship and exhortation honoring Lord Kelvin's maxim: "When you cannot measure, your knowledge is meager and unsatisfactory."' This article is about that tradition, but not of that tradition. It differs from articles in this symposium that draw hypotheses and seek to disprove them by repeated observations. It is, rather, a case study of the creation of the Federal Judicial Center, 2 the federal courts' research and education agency and an important contributor to empiricism in civil procedure. This article indicates that changes in court organization, including changes to promote quantitative research, are likely to reflect developments in the larger environment of which the courts are a part. It highlights some characteristics about the politics of empirical research on procedure. It suggests that numerous interests seek to control internal research activity within the judicial branch. Beyond these points, the episodes of judicial lobbying that this article reveals remind us that predictions of human behavior, the ultimate goal of social science empirical theory, are always subject to the influence of fortuitous circumstances-chance always plays a role. II QUANTITATIVE PROCEDURE RESEARCH IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY Efforts to measure the effect of legal and procedural rules date back at least to the Progressive Era at the turn of the century, an era dominated by Copyright © 1988 by Law and Contemporary Problems * Director, Division of Special Educational Services, Federal Judicial Center.