Microstructure and Composition of Marine Aggregates As Co-Determinants for Vertical Particulate Organic Carbon Transfer in the Global Ocean Joeran Maerz1, Katharina D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Methane Cold Seeps As Biological Oases in the High‐

LIMNOLOGY and Limnol. Oceanogr. 00, 2017, 00–00 VC 2017 The Authors Limnology and Oceanography published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. OCEANOGRAPHY on behalf of Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography doi: 10.1002/lno.10732 Methane cold seeps as biological oases in the high-Arctic deep sea Emmelie K. L. A˚ strom€ ,1* Michael L. Carroll,1,2 William G. Ambrose, Jr.,1,2,3,4 Arunima Sen,1 Anna Silyakova,1 JoLynn Carroll1,2 1CAGE - Centre for Arctic Gas Hydrate, Environment and Climate, Department of Geosciences, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway 2Akvaplan-niva, FRAM – High North Research Centre for Climate and the Environment, Tromsø, Norway 3Division of Polar Programs, National Science Foundation, Arlington, Virginia 4Department of Biology, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine Abstract Cold seeps can support unique faunal communities via chemosynthetic interactions fueled by seabed emissions of hydrocarbons. Additionally, cold seeps can enhance habitat complexity at the deep seafloor through the accretion of methane derived authigenic carbonates (MDAC). We examined infaunal and mega- faunal community structure at high-Arctic cold seeps through analyses of benthic samples and seafloor pho- tographs from pockmarks exhibiting highly elevated methane concentrations in sediments and the water column at Vestnesa Ridge (VR), Svalbard (798 N). Infaunal biomass and abundance were five times higher, species richness was 2.5 times higher and diversity was 1.5 times higher at methane-rich Vestnesa compared to a nearby control region. Seabed photos reveal different faunal associations inside, at the edge, and outside Vestnesa pockmarks. Brittle stars were the most common megafauna occurring on the soft bottom plains out- side pockmarks. -

CP-2019-161 Lessons from a High CO2 World: an Ocean View from ~3 Million Years Ago Reply to Editor

CP-2019-161 Lessons from a high CO2 world: an ocean view from ~3 million years ago Reply to Editor This document addresses the concerns of the Editor on our revised manuscript. We also include the “tracked changes” manuscript text. No changes have been made to the Supplement text. We thank the Editor for the remaining comments, which are addressed here and shown as tracked changes in the document below: Upon final reading of the manuscript I noticed 2 areas, that I feel need addressing before the manuscript can be published. These are minor and the second I think is a result of some changes you made to the manuscript in the most recent submission. 1. Please reference the underlying SST data in Figure 2. At present, the figure caption only makes reference to the the PlioVAR sites. Thank you for flagging this, we had omitted to cite our source data. The PlioVAR sites have been overlaid on the World Ocean Atlas (2018) mean annual SSTs. We have cited this source in the caption. We also felt that we should highlight that the compiled information on sites and proxies is included in the Supplement file and in the Pangaea archive. Our caption has been edited accordingly: Figure 2: Locations of sites used in the synthesis, overlain on mean annual SST data from the World Ocean Atlas 2018 (Locarnini et al., 2018). A full list of the data sources and K proxies applied per site are available in Table S3 (U 37’) and Table S4 (Mg/Ca), and can be accessed at https://pliovar.github.io/km5c.html. -

World Ocean Thermocline Weakening and Isothermal Layer Warming

applied sciences Article World Ocean Thermocline Weakening and Isothermal Layer Warming Peter C. Chu * and Chenwu Fan Naval Ocean Analysis and Prediction Laboratory, Department of Oceanography, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA 93943, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-831-656-3688 Received: 30 September 2020; Accepted: 13 November 2020; Published: 19 November 2020 Abstract: This paper identifies world thermocline weakening and provides an improved estimate of upper ocean warming through replacement of the upper layer with the fixed depth range by the isothermal layer, because the upper ocean isothermal layer (as a whole) exchanges heat with the atmosphere and the deep layer. Thermocline gradient, heat flux across the air–ocean interface, and horizontal heat advection determine the heat stored in the isothermal layer. Among the three processes, the effect of the thermocline gradient clearly shows up when we use the isothermal layer heat content, but it is otherwise when we use the heat content with the fixed depth ranges such as 0–300 m, 0–400 m, 0–700 m, 0–750 m, and 0–2000 m. A strong thermocline gradient exhibits the downward heat transfer from the isothermal layer (non-polar regions), makes the isothermal layer thin, and causes less heat to be stored in it. On the other hand, a weak thermocline gradient makes the isothermal layer thick, and causes more heat to be stored in it. In addition, the uncertainty in estimating upper ocean heat content and warming trends using uncertain fixed depth ranges (0–300 m, 0–400 m, 0–700 m, 0–750 m, or 0–2000 m) will be eliminated by using the isothermal layer. -

New Constraints on Ocean Carbon

Ref. Ares(2020)7216916 - 30/11/2020 New constraints on ocean carbon Deliverable D1.6 Authors: Peter Landschützer, Nicolas Gruber, Jens D. Müller, Lydia Keppler, Luke Gregor This project received funding from the Horizon 2020 programme under the grant agreement No. 821003. Document Information GRANT AGREEMENT 821003 PROJECT TITLE Climate Carbon Interactions in the Current Century PROJECT ACRONYM 4C PROJECT START 1/6/2019 DATE RELATED WORK W1 PACKAGE RELATED TASK(S) T1.2.1, T1.2.2 LEAD MPG ORGANIZATION AUTHORS P. Landschützer, N. Gruber, J.D. Müller, L. Keppler and L. Gregor SUBMISSION DATE x DISSEMINATION PU / CO / DE LEVEL History DATE SUBMITTED BY REVIEWED BY VISION (NOTES) 18.11.2020 Peter Landschützet (MPG) P. Friedlingstein (UNEXE) Please cite this report as: P. Landschützer, N. Gruber, J.D. Müller, L. Keppler and L. Gregor, (2020), New constraints on ocean carbon, D1.6 of the 4C project Disclaimer: The content of this deliverable reflects only the author’s view. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. D1.6 New constraints on ocean carbon| 1 Table of Contents 2 New observation-based constraints on the surface ocean carbonate system and the air-sea CO2 flux 5 2.1 OceanSODA-ETHZ 5 2.1.1 Observations 5 2.1.2 Method 5 2.1.3 Results 6 2.1.4 Data availability 7 2.1.5 References 7 2.2 Update of MPI-SOMFFN and new MPI-ULB-SOMFFN-clim 8 2.2.1 Observations 9 2.2.2 Method 9 2.2.3 Results 9 2.2.4 Data availability 10 2.2.5 References 11 3 New observation-based constraints on interior -

Brochure.Pdf

Two Little Fishies Two Little Fishies Inc. 4016 El Prado Blvd., Coconut Grove, Florida 33133 U.S.A. Tel (+01) 305 661.7742 Fax (+01) 305 661.0611 eMail: [email protected] ww w. t w o l i t t l e f i s h i e s . c o m © 2004 Two Little Fishies Inc. Two Little Fishies is a registered trademark of Two Little Fishies Inc.. All illustrations, photos and specifications contained in this broc h u r e are based on the latest pr oduct information available at the time of publication. Two Little Fishies Inc. res e r ves the right to make changes at any time, without notice. Printed in USA V.4 _ 2 0 0 4 Simple, Elegant, Practical,Solutions Useful... Two Little Fishies Two Little Fishies, Inc. was founded in 1991 to pr omote the reef aquarium hobby with its in t ro d u c t o r y video and books about ree f aquariums. The company now publishes and distributes the most popular reef aquarium ref e r ence books and identification guides in English, German French and Italian, under the d.b.a. Ricordea Publishing. Since its small beginning, Two Little Fishies has also grown to become a manufacturer and im p o r ter of the highest quality products for aquariums and water gardens, with interna t i o n a l distribution in the pet, aquaculture, and water ga r den industries. Two Little Fishies’ prod u c t line includes trace element supplements, calcium supplements and buffers, phosphate- fr ee activated carbon, granular iron - b a s e d phosphate adsorption media, underwa t e r bonding compounds, and specialty foods for fish and invertebrates. -

Ch. 9: Ocean Biogeochemistry

6/3/13 Ch. 9: Ocean Biogeochemistry NOAA photo gallery Overview • The Big Picture • Ocean Circulation • Seawater Composition • Marine NPP • Particle Flux: The Biological Pump • Carbon Cycling • Nutrient Cycling • Time Pemitting: Hydrothermal venting, Sulfur cycling, Sedimentary record, El Niño • Putting It All Together Slides borrowed from Aradhna Tripati 1 6/3/13 Ocean Circulation • Upper Ocean is wind-driven and well mixed • Surface Currents deflected towards the poles by land. • Coriolis force deflects currents away from the wind, forming mid-ocean gyres • Circulation moves heat poleward • River influx is to surface ocean • Atmospheric equilibrium is with surface ocean • Primary productivity is in the surface ocean Surface Currents 2 6/3/13 Deep Ocean Circulation • Deep and Surface Oceans separated by density gradient caused by differences in Temperature and Salinity • This drives thermohaline deep circulation: * Ice forms in the N. Atlantic and Southern Ocean, leaving behind cold, saline water which sinks * Oldest water is in N. Pacific * Distribution of dissolved gases and nutrients: N, P, CO2 Seawater Composition • Salinity is defined as grams of salt/kg seawater, or parts per thousand: %o • Major ions are in approximately constant concentrations everywhere in the oceans • Salts enter in river water, and are removed by porewater burial, sea spray and evaporites (Na, Cl). • Calcium and Sulfate are removed in biogenic sediments • Magnesium is consumed in hydrothermal vents, in ionic exchange for Ca in rock. • Potassium adsorbs in clays. 3 6/3/13 Major Ions in Seawater The Two-Box Model of the Ocean Precipitation Evaporation River Flow Upwelling Downwelling Particle Flux Sedimentation 4 6/3/13 Residence time vs. -

The Difference of Sea Level Variability by Steric Height and Altimetry In

remote sensing Letter The Difference of Sea Level Variability by Steric Height and Altimetry in the North Pacific Qianran Zhang 1, Fangjie Yu 1,2,* and Ge Chen 1,2 1 College of Information Science and Engineering, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266100, China; [email protected] (Q.Z.); [email protected] (G.C.) 2 Laboratory for Regional Oceanography and Numerical Modeling, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266200, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-0532-66782155 Received: 4 December 2019; Accepted: 22 January 2020; Published: 24 January 2020 Abstract: Sea level variability, which is less than ~100 km in scale, is important in upper-ocean circulation dynamics and is difficult to observe by existing altimetry observations; thus, interferometric altimetry, which effectively provides high-resolution observations over two swaths, was developed. However, validating the sea level variability in two dimensions is a difficult task. In theory, using the steric method to validate height variability in different pixels is feasible and has already been proven by modelled and altimetry gridded data. In this paper, we use Argo data around a typical mesoscale eddy and altimetry along-track data in the North Pacific to analyze the relationship between steric data and along-track data (SD-AD) at two points, which indicates the feasibility of the steric method. We also analyzed the result of SD-AD by the relationship of the distance of the Argo and the satellite in Point 1 (P1) and Point 2 (P2), the relationship of two Argo positions, the relationship of the distance between Argo positions and the eddy center and the relationship of the wind. -

NOAA Atlas NESDIS 81 WORLD OCEAN ATLAS 2018 Volume 1

NOAA Atlas NESDIS 81 WORLD OCEAN ATLAS 2018 Volume 1: Temperature Silver Spring, MD July 2019 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service National Centers for Environmental Information NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information Additional copies of this publication, as well as information about NCEI data holdings and services, are available upon request directly from NCEI. NOAA/NESDIS National Centers for Environmental Information SSMC3, 4th floor 1315 East-West Highway Silver Spring, MD 20910-3282 Telephone: (301) 713-3277 E-mail: [email protected] WEB: http://www.nodc.noaa.gov/ For updates on the data, documentation, and additional information about the WOA18 please refer to: http://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/indprod.html This document should be cited as: Locarnini, R.A., A.V. Mishonov, O.K. Baranova, T.P. Boyer, M.M. Zweng, H.E. Garcia, J.R. Reagan, D. Seidov, K.W. Weathers, C.R. Paver, and I.V. Smolyar (2019). World Ocean Atlas 2018, Volume 1: Temperature. A. Mishonov, Technical Editor. NOAA Atlas NESDIS 81, 52pp. This document is available on line at http://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/indprod.html . NOAA Atlas NESDIS 81 WORLD OCEAN ATLAS 2018 Volume 1: Temperature Ricardo A. Locarnini, Alexey V. Mishonov, Olga K. Baranova, Timothy P. Boyer, Melissa M. Zweng, Hernan E. Garcia, James R. Reagan, Dan Seidov, Katharine W. Weathers, Christopher R. Paver, Igor V. Smolyar Technical Editor: Alexey Mishonov Ocean Climate Laboratory National Centers for Environmental Information Silver Spring, Maryland July 2019 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Wilbur L. -

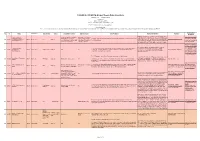

OCEAN ACCOUNTS Global Ocean Data Inventory Version 1.0 13 Dec 2019 Lyutong CAI Statistics Division, ESCAP Email: [email protected] Or [email protected]

OCEAN ACCOUNTS Global Ocean Data Inventory Version 1.0 13 Dec 2019 Lyutong CAI Statistics Division, ESCAP Email: [email protected] or [email protected] ESCAP Statistics Division: [email protected] Acknowledgments The author is thankful for the pre-research done by Michael Bordt (Global Ocean Accounts Partnership co-chair) and Yilun Luo (ESCAP), the contribution from Feixue Li (Nanjing University) and suggestions from Teerapong Praphotjanaporn (ESCAP). Introduction No. ID Name Component Data format Status Acquisition method Data resolution Data Available Further information Website Document CMECS is designed for use within all waters ranging from the Includes the physical, biological, Not limited to specific gear https://iocm.noaa.gov/c Coastal and Marine head of tide to the limits of the exclusive economic zone, and and chemical data that are types or to observations A comprehensive national framework for organizing information about coasts and oceans and mecs/documents/CME 001 SU-001 Ecological Classification Single Spatial units N/A Ongoing from the spray zone to the deep ocean. It is compatible with https://iocm.noaa.gov/cmecs/ collectively used to define coastal made at specific spatial or their living systems. CS_One_Page_Descrip Standard(CMECS) many existing upland and wetland classification standards and and marine ecosystems temporal resolutions tion-20160518.pdf can be used with most if not all data collection technologies. https://www.researchga te.net/publication/32889 The Combined Biotope Classification Scheme (CBiCS) 1619_Combined_Bioto Combined Biotope It is a hierarchical classification of marine biotopes, including aquatic setting, biogeographic combines the core elements of the CMECS habitat pe_Classification_Sche 002 SU-002 Classification Single Spatial units Onlline viewer Ongoing N/A N/A setting, water column component, substrate component, geoform component, biotic http://www.cbics.org/about/ classification scheme and the JNCC/EUNIS biotope me_CBiCS_A_New_M Scheme(SBiCS) component, morphospecies component. -

Oxygen, Apparent Oxygen Utilization, and Dissolved Oxygen Saturation

NOAA Atlas NESDIS 83 WORLD OCEAN ATLAS 2018 Volume 3: Dissolved Oxygen, Apparent Oxygen Utilization, and Dissolved Oxygen Saturation Silver Spring, MD July 2019 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service National Centers for Environmental Information NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information Additional copies of this publication, as well as information about NCEI data holdings and services, are available upon request directly from NCEI. NOAA/NESDIS National Centers for Environmental Information SSMC3, 4th floor 1315 East-West Highway Silver Spring, MD 20910-3282 Telephone: (301) 713-3277 E-mail: [email protected] WEB: http://www.nodc.noaa.gov/ For updates on the data, documentation, and additional information about the WOA18 please refer to: http://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/indprod.html This document should be cited as: Garcia H. E., K.W. Weathers, C.R. Paver, I. Smolyar, T.P. Boyer, R.A. Locarnini, M.M. Zweng, A.V. Mishonov, O.K. Baranova, D. Seidov, and J.R. Reagan (2019). World Ocean Atlas 2018, Volume 3: Dissolved Oxygen, Apparent Oxygen Utilization, and Dissolved Oxygen Saturation. A. Mishonov Technical Editor. NOAA Atlas NESDIS 83, 38pp. This document is available on-line at https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/woa18/pubwoa18.html NOAA Atlas NESDIS 83 WORLD OCEAN ATLAS 2018 Volume 3: Dissolved Oxygen, Apparent Oxygen Utilization, and Dissolved Oxygen Saturation Hernan E. Garcia, Katharine W. Weathers, Chris R. Paver, Igor Smolyar, Timothy P. Boyer, Ricardo A. Locarnini, Melissa M. Zweng, Alexey V. Mishonov, Olga K. Baranova, Dan Seidov, James R. -

Ocean Primary Production

Learning Ocean Science through Ocean Exploration Section 6 Ocean Primary Production Photosynthesis very ecosystem requires an input of energy. The Esource varies with the system. In the majority of ocean ecosystems the source of energy is sunlight that drives photosynthesis done by micro- (phytoplankton) or macro- (seaweeds) algae, green plants, or photosynthetic blue-green or purple bacteria. These organisms produce ecosystem food that supports the food chain, hence they are referred to as primary producers. The balanced equation for photosynthesis that is correct, but seldom used, is 6CO2 + 12H2O = C6H12O6 + 6H2O + 6O2. Water appears on both sides of the equation because the water molecule is split, and new water molecules are made in the process. When the correct equation for photosynthe- sis is used, it is easier to see the similarities with chemo- synthesis in which water is also a product. Systems Lacking There are some ecosystems that depend on primary Primary Producers production from other ecosystems. Many streams have few primary producers and are dependent on the leaves from surrounding forests as a source of food that supports the stream food chain. Snow fields in the high mountains and sand dunes in the desert depend on food blown in from areas that support primary production. The oceans below the photic zone are a vast space, largely dependent on food from photosynthetic primary producers living in the sunlit waters above. Food sinks to the bottom in the form of dead organisms and bacteria. It is as small as marine snow—tiny clumps of bacteria and decomposing microalgae—and as large as an occasional bonanza—a dead whale. -

Eukaryotic Microbes, Principally Fungi and Labyrinthulomycetes, Dominate Biomass on Bathypelagic Marine Snow

The ISME Journal (2017) 11, 362–373 © 2017 International Society for Microbial Ecology All rights reserved 1751-7362/17 www.nature.com/ismej ORIGINAL ARTICLE Eukaryotic microbes, principally fungi and labyrinthulomycetes, dominate biomass on bathypelagic marine snow Alexander B Bochdansky1, Melissa A Clouse1 and Gerhard J Herndl2 1Ocean, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA, USA and 2Department of Limnology and Bio-Oceanography, Division of Bio-Oceanography, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria In the bathypelagic realm of the ocean, the role of marine snow as a carbon and energy source for the deep-sea biota and as a potential hotspot of microbial diversity and activity has not received adequate attention. Here, we collected bathypelagic marine snow by gentle gravity filtration of sea water onto 30 μm filters from ~ 1000 to 3900 m to investigate the relative distribution of eukaryotic microbes. Compared with sediment traps that select for fast-sinking particles, this method collects particles unbiased by settling velocity. While prokaryotes numerically exceeded eukaryotes on marine snow, eukaryotic microbes belonging to two very distant branches of the eukaryote tree, the fungi and the labyrinthulomycetes, dominated overall biomass. Being tolerant to cold temperature and high hydrostatic pressure, these saprotrophic organisms have the potential to significantly contribute to the degradation of organic matter in the deep sea. Our results demonstrate that the community composition on bathypelagic marine snow differs greatly from that in the ambient water leading to wide ecological niche separation between the two environments. The ISME Journal (2017) 11, 362–373; doi:10.1038/ismej.2016.113; published online 20 September 2016 Introduction or dense phytodetritus, but a large amount of transparent exopolymer particles (TEP, Alldredge Deep-sea life is greatly dependent on the particulate et al., 1993), which led us to conclude that they organic matter (POM) flux from the euphotic layer.