A 2004-06 Ocean Atlas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CP-2019-161 Lessons from a High CO2 World: an Ocean View from ~3 Million Years Ago Reply to Editor

CP-2019-161 Lessons from a high CO2 world: an ocean view from ~3 million years ago Reply to Editor This document addresses the concerns of the Editor on our revised manuscript. We also include the “tracked changes” manuscript text. No changes have been made to the Supplement text. We thank the Editor for the remaining comments, which are addressed here and shown as tracked changes in the document below: Upon final reading of the manuscript I noticed 2 areas, that I feel need addressing before the manuscript can be published. These are minor and the second I think is a result of some changes you made to the manuscript in the most recent submission. 1. Please reference the underlying SST data in Figure 2. At present, the figure caption only makes reference to the the PlioVAR sites. Thank you for flagging this, we had omitted to cite our source data. The PlioVAR sites have been overlaid on the World Ocean Atlas (2018) mean annual SSTs. We have cited this source in the caption. We also felt that we should highlight that the compiled information on sites and proxies is included in the Supplement file and in the Pangaea archive. Our caption has been edited accordingly: Figure 2: Locations of sites used in the synthesis, overlain on mean annual SST data from the World Ocean Atlas 2018 (Locarnini et al., 2018). A full list of the data sources and K proxies applied per site are available in Table S3 (U 37’) and Table S4 (Mg/Ca), and can be accessed at https://pliovar.github.io/km5c.html. -

World Ocean Thermocline Weakening and Isothermal Layer Warming

applied sciences Article World Ocean Thermocline Weakening and Isothermal Layer Warming Peter C. Chu * and Chenwu Fan Naval Ocean Analysis and Prediction Laboratory, Department of Oceanography, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA 93943, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-831-656-3688 Received: 30 September 2020; Accepted: 13 November 2020; Published: 19 November 2020 Abstract: This paper identifies world thermocline weakening and provides an improved estimate of upper ocean warming through replacement of the upper layer with the fixed depth range by the isothermal layer, because the upper ocean isothermal layer (as a whole) exchanges heat with the atmosphere and the deep layer. Thermocline gradient, heat flux across the air–ocean interface, and horizontal heat advection determine the heat stored in the isothermal layer. Among the three processes, the effect of the thermocline gradient clearly shows up when we use the isothermal layer heat content, but it is otherwise when we use the heat content with the fixed depth ranges such as 0–300 m, 0–400 m, 0–700 m, 0–750 m, and 0–2000 m. A strong thermocline gradient exhibits the downward heat transfer from the isothermal layer (non-polar regions), makes the isothermal layer thin, and causes less heat to be stored in it. On the other hand, a weak thermocline gradient makes the isothermal layer thick, and causes more heat to be stored in it. In addition, the uncertainty in estimating upper ocean heat content and warming trends using uncertain fixed depth ranges (0–300 m, 0–400 m, 0–700 m, 0–750 m, or 0–2000 m) will be eliminated by using the isothermal layer. -

Role of Regional Ocean Dynamics in Dynamic Sea Level Projections by the End of the 21St Century Over Southeast Asia

EGU21-8618, updated on 25 Sep 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu21-8618 EGU General Assembly 2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Role of Regional Ocean Dynamics in Dynamic Sea Level Projections by the end of the 21st Century over Southeast Asia Dhrubajyoti Samanta1, Svetlana Jevrejeva2, Hindumathi K. Palanisamy2, Kristopher B. Karnauskas3, Nathalie F. Goodkin1,4, and Benjamin P. Horton1 1Nanyang Technological University, Singapore ([email protected]) 2Centre for Climate Research Singapore, Singapore 3University of Colorado Boulder, USA 4American Museum of Natural History, USA Southeast Asia is especially vulnerable to the impacts of sea-level rise due to the presence of many low-lying small islands and highly populated coastal cities. However, our current understanding of sea-level projections and changes in upper-ocean dynamics over this region currently rely on relatively coarse resolution (~100 km) global climate model (GCM) simulations and is therefore limited over the coastal regions. Here using GCM simulations from the High-Resolution Model Intercomparison Project (HighResMIP) of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) to (1) examine the improvement of mean-state biases in the tropical Pacific and dynamic sea-level (DSL) over Southeast Asia; (2) generate projection on DSL over Southeast Asia under shared socioeconomic pathways phase-5 (SSP5-585); and (3) diagnose the role of changes in regional ocean dynamics under SSP5-585. We select HighResMIP models that included a historical period and shared socioeconomic pathways (SSP) 5-8.5 future scenario for the same ensemble and estimate the projected changes relative to the 1993-2014 period. -

Download Service

Vol. 62 Bollettino Vol. 62 - SUPPLEMENT 1 pp. 327 di Geofisica An International teorica ed applicata Journal of Earth Sciences IMDIS 2021 International Conference on Marine Data and Information Systems 12-14 April, 2021 Online Book of Abstracts SUPPLEMENT 1 Guest Editors: Michèle Fichaut, Vanessa Tosello, Alessandra Giorgetti BOLLETTINO DI GEOFISICA teorica ed applicata 210109 - OGS.Supp.Vol62.cover_08dorso19.indd 3 03/05/21 10:54 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF D. Slejko; Trieste, Italy EDITORIAL COUNCIL SUBSCRIPTIONS 2021 A. Camerlenghi, N. Casagli, F. Coren, P. Del Negro, F. Ferraccioli, S. Parolai, G. Rossi, C. Solidoro; Trieste, Italy ASSOCIATE EDITORS A. SOLID EaRTH GeOPHYsICs N. Abu-Zeid; Ferrara, Italy J. Ba; Nanjing, China R. Barzaghi; Milano, Italy J. Boaga; Padova, Italy C. Braitenberg; Trieste, Italy A. Casas; Barcelona, Spain G. Cassiani; Padova, Italy F. Cavallini; Trieste, Italy A. Del Ben; Trieste, Italy P. dell’Aversana; San Donato Milanese, Italy C. Doglioni; Roma, Italy F. Ferrucci, Vibo Valentia, Italy E. Forte; Trieste, Italy M.-J. Jimenez; Madrid, Spain C. Layland-Bachmann, Berkeley, U.S.A. Bollettino di Geofisica Teorica ed Applicata G. Li; Zhoushan, China c/o Istituto Nazionale di Oceanografia P. Paganini; Trieste, Italy e di Geofisica Sperimentale V. Paoletti, Naples, Italy Borgo Grotta Gigante, 42/c E. Papadimitriou; Thessaloniki, Greece 34010 Sgonico, Trieste, Italy R. Petrini; Pisa, Italy e-mail: [email protected] M. Pipan; Trieste, Italy G. Seriani; Trieste, Italy http-server: bgta.eu A. Shogenova; Tallin, Estonia E. Stucchi; Milano, Italy S. Trevisani; Venezia, Italy M. Vellico; Trieste, Italy A. Vesnaver; Trieste, Italy V. Volpi; Trieste, Italy A. -

New Constraints on Ocean Carbon

Ref. Ares(2020)7216916 - 30/11/2020 New constraints on ocean carbon Deliverable D1.6 Authors: Peter Landschützer, Nicolas Gruber, Jens D. Müller, Lydia Keppler, Luke Gregor This project received funding from the Horizon 2020 programme under the grant agreement No. 821003. Document Information GRANT AGREEMENT 821003 PROJECT TITLE Climate Carbon Interactions in the Current Century PROJECT ACRONYM 4C PROJECT START 1/6/2019 DATE RELATED WORK W1 PACKAGE RELATED TASK(S) T1.2.1, T1.2.2 LEAD MPG ORGANIZATION AUTHORS P. Landschützer, N. Gruber, J.D. Müller, L. Keppler and L. Gregor SUBMISSION DATE x DISSEMINATION PU / CO / DE LEVEL History DATE SUBMITTED BY REVIEWED BY VISION (NOTES) 18.11.2020 Peter Landschützet (MPG) P. Friedlingstein (UNEXE) Please cite this report as: P. Landschützer, N. Gruber, J.D. Müller, L. Keppler and L. Gregor, (2020), New constraints on ocean carbon, D1.6 of the 4C project Disclaimer: The content of this deliverable reflects only the author’s view. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. D1.6 New constraints on ocean carbon| 1 Table of Contents 2 New observation-based constraints on the surface ocean carbonate system and the air-sea CO2 flux 5 2.1 OceanSODA-ETHZ 5 2.1.1 Observations 5 2.1.2 Method 5 2.1.3 Results 6 2.1.4 Data availability 7 2.1.5 References 7 2.2 Update of MPI-SOMFFN and new MPI-ULB-SOMFFN-clim 8 2.2.1 Observations 9 2.2.2 Method 9 2.2.3 Results 9 2.2.4 Data availability 10 2.2.5 References 11 3 New observation-based constraints on interior -

Shallow Water Waves and Solitary Waves Article Outline Glossary

Shallow Water Waves and Solitary Waves Willy Hereman Department of Mathematical and Computer Sciences, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, Colorado, USA Article Outline Glossary I. Definition of the Subject II. Introduction{Historical Perspective III. Completely Integrable Shallow Water Wave Equations IV. Shallow Water Wave Equations of Geophysical Fluid Dynamics V. Computation of Solitary Wave Solutions VI. Water Wave Experiments and Observations VII. Future Directions VIII. Bibliography Glossary Deep water A surface wave is said to be in deep water if its wavelength is much shorter than the local water depth. Internal wave A internal wave travels within the interior of a fluid. The maximum velocity and maximum amplitude occur within the fluid or at an internal boundary (interface). Internal waves depend on the density-stratification of the fluid. Shallow water A surface wave is said to be in shallow water if its wavelength is much larger than the local water depth. Shallow water waves Shallow water waves correspond to the flow at the free surface of a body of shallow water under the force of gravity, or to the flow below a horizontal pressure surface in a fluid. Shallow water wave equations Shallow water wave equations are a set of partial differential equations that describe shallow water waves. 1 Solitary wave A solitary wave is a localized gravity wave that maintains its coherence and, hence, its visi- bility through properties of nonlinear hydrodynamics. Solitary waves have finite amplitude and propagate with constant speed and constant shape. Soliton Solitons are solitary waves that have an elastic scattering property: they retain their shape and speed after colliding with each other. -

An Unconditionally Stable Scheme for the Shallow Water Equations*

810 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 128 An Unconditionally Stable Scheme for the Shallow Water Equations* MOSHE ISRAELI Computer Science Department, Technion, Haifa, Israel NAOMI H. NAIK AND MARK A. CANE Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, New York (Manuscript received 24 September 1998, in ®nal form 1 March 1999) ABSTRACT A ®nite-difference scheme for solving the linear shallow water equations in a bounded domain is described. Its time step is not restricted by a Courant±Friedrichs±Levy (CFL) condition. The scheme, known as Israeli± Naik±Cane (INC), is the offspring of semi-Lagrangian (SL) schemes and the Cane±Patton (CP) algorithm. In common with the latter it treats the shallow water equations implicitly in y and with attention to wave propagation in x. Unlike CP, it uses an SL-like approach to the zonal variations, which allows the scheme to apply to the full primitive equations. The great advantage, even in problems where quasigeostrophic dynamics are appropriate in the interior, is that the INC scheme accommodates complete boundary conditions. 1. Introduction is easy to code and boundary conditions for the discre- The two-dimensional linearized shallow water equa- tized equations are fairly natural to impose. At the other tions represent the evolution of small perturbations in end of the spectrum, the CP algorithm is speci®cally the ¯ow ®eld of a shallow basin on a rotating sphere. designed with the characteristics of the physics of the Our interest in these model equations arises from our equatorial ocean dynamics in mind. By separating the interest in solving for the motions in a linear beta-plane free modes into the eastward propagating Kelvin mode deep ocean. -

Geophysical Fluid Dynamics, Nonautonomous Dynamical Systems, and the Climate Sciences

Geophysical Fluid Dynamics, Nonautonomous Dynamical Systems, and the Climate Sciences Michael Ghil and Eric Simonnet Abstract This contribution introduces the dynamics of shallow and rotating flows that characterizes large-scale motions of the atmosphere and oceans. It then focuses on an important aspect of climate dynamics on interannual and interdecadal scales, namely the wind-driven ocean circulation. Studying the variability of this circulation and slow changes therein is treated as an application of the theory of nonautonomous dynamical systems. The contribution concludes by discussing the relevance of these mathematical concepts and methods for the highly topical issues of climate change and climate sensitivity. Michael Ghil Ecole Normale Superieure´ and PSL Research University, Paris, FRANCE, and University of California, Los Angeles, USA, e-mail: [email protected] Eric Simonnet Institut de Physique de Nice, CNRS & Universite´ Coteˆ d’Azur, Nice Sophia-Antipolis, FRANCE, e-mail: [email protected] 1 Chapter 1 Effects of Rotation The first two chapters of this contribution are dedicated to an introductory review of the effects of rotation and shallowness om large-scale planetary flows. The theory of such flows is commonly designated as geophysical fluid dynamics (GFD), and it applies to both atmospheric and oceanic flows, on Earth as well as on other planets. GFD is now covered, at various levels and to various extents, by several books [36, 60, 72, 107, 120, 134, 164]. The virtue, if any, of this presentation is its brevity and, hopefully, clarity. It fol- lows most closely, and updates, Chapters 1 and 2 in [60]. The intended audience in- cludes the increasing number of mathematicians, physicists and statisticians that are becoming interested in the climate sciences, as well as climate scientists from less traditional areas — such as ecology, glaciology, hydrology, and remote sensing — who wish to acquaint themselves with the large-scale dynamics of the atmosphere and oceans. -

The Difference of Sea Level Variability by Steric Height and Altimetry In

remote sensing Letter The Difference of Sea Level Variability by Steric Height and Altimetry in the North Pacific Qianran Zhang 1, Fangjie Yu 1,2,* and Ge Chen 1,2 1 College of Information Science and Engineering, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266100, China; [email protected] (Q.Z.); [email protected] (G.C.) 2 Laboratory for Regional Oceanography and Numerical Modeling, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266200, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-0532-66782155 Received: 4 December 2019; Accepted: 22 January 2020; Published: 24 January 2020 Abstract: Sea level variability, which is less than ~100 km in scale, is important in upper-ocean circulation dynamics and is difficult to observe by existing altimetry observations; thus, interferometric altimetry, which effectively provides high-resolution observations over two swaths, was developed. However, validating the sea level variability in two dimensions is a difficult task. In theory, using the steric method to validate height variability in different pixels is feasible and has already been proven by modelled and altimetry gridded data. In this paper, we use Argo data around a typical mesoscale eddy and altimetry along-track data in the North Pacific to analyze the relationship between steric data and along-track data (SD-AD) at two points, which indicates the feasibility of the steric method. We also analyzed the result of SD-AD by the relationship of the distance of the Argo and the satellite in Point 1 (P1) and Point 2 (P2), the relationship of two Argo positions, the relationship of the distance between Argo positions and the eddy center and the relationship of the wind. -

NOAA Atlas NESDIS 81 WORLD OCEAN ATLAS 2018 Volume 1

NOAA Atlas NESDIS 81 WORLD OCEAN ATLAS 2018 Volume 1: Temperature Silver Spring, MD July 2019 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service National Centers for Environmental Information NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information Additional copies of this publication, as well as information about NCEI data holdings and services, are available upon request directly from NCEI. NOAA/NESDIS National Centers for Environmental Information SSMC3, 4th floor 1315 East-West Highway Silver Spring, MD 20910-3282 Telephone: (301) 713-3277 E-mail: [email protected] WEB: http://www.nodc.noaa.gov/ For updates on the data, documentation, and additional information about the WOA18 please refer to: http://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/indprod.html This document should be cited as: Locarnini, R.A., A.V. Mishonov, O.K. Baranova, T.P. Boyer, M.M. Zweng, H.E. Garcia, J.R. Reagan, D. Seidov, K.W. Weathers, C.R. Paver, and I.V. Smolyar (2019). World Ocean Atlas 2018, Volume 1: Temperature. A. Mishonov, Technical Editor. NOAA Atlas NESDIS 81, 52pp. This document is available on line at http://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/indprod.html . NOAA Atlas NESDIS 81 WORLD OCEAN ATLAS 2018 Volume 1: Temperature Ricardo A. Locarnini, Alexey V. Mishonov, Olga K. Baranova, Timothy P. Boyer, Melissa M. Zweng, Hernan E. Garcia, James R. Reagan, Dan Seidov, Katharine W. Weathers, Christopher R. Paver, Igor V. Smolyar Technical Editor: Alexey Mishonov Ocean Climate Laboratory National Centers for Environmental Information Silver Spring, Maryland July 2019 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Wilbur L. -

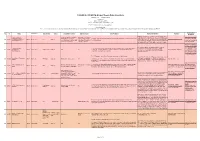

OCEAN ACCOUNTS Global Ocean Data Inventory Version 1.0 13 Dec 2019 Lyutong CAI Statistics Division, ESCAP Email: [email protected] Or [email protected]

OCEAN ACCOUNTS Global Ocean Data Inventory Version 1.0 13 Dec 2019 Lyutong CAI Statistics Division, ESCAP Email: [email protected] or [email protected] ESCAP Statistics Division: [email protected] Acknowledgments The author is thankful for the pre-research done by Michael Bordt (Global Ocean Accounts Partnership co-chair) and Yilun Luo (ESCAP), the contribution from Feixue Li (Nanjing University) and suggestions from Teerapong Praphotjanaporn (ESCAP). Introduction No. ID Name Component Data format Status Acquisition method Data resolution Data Available Further information Website Document CMECS is designed for use within all waters ranging from the Includes the physical, biological, Not limited to specific gear https://iocm.noaa.gov/c Coastal and Marine head of tide to the limits of the exclusive economic zone, and and chemical data that are types or to observations A comprehensive national framework for organizing information about coasts and oceans and mecs/documents/CME 001 SU-001 Ecological Classification Single Spatial units N/A Ongoing from the spray zone to the deep ocean. It is compatible with https://iocm.noaa.gov/cmecs/ collectively used to define coastal made at specific spatial or their living systems. CS_One_Page_Descrip Standard(CMECS) many existing upland and wetland classification standards and and marine ecosystems temporal resolutions tion-20160518.pdf can be used with most if not all data collection technologies. https://www.researchga te.net/publication/32889 The Combined Biotope Classification Scheme (CBiCS) 1619_Combined_Bioto Combined Biotope It is a hierarchical classification of marine biotopes, including aquatic setting, biogeographic combines the core elements of the CMECS habitat pe_Classification_Sche 002 SU-002 Classification Single Spatial units Onlline viewer Ongoing N/A N/A setting, water column component, substrate component, geoform component, biotic http://www.cbics.org/about/ classification scheme and the JNCC/EUNIS biotope me_CBiCS_A_New_M Scheme(SBiCS) component, morphospecies component. -

MAR 542 – Fundamentals of Atmosphere and Ocean Dynamics Instructor: Marat Khairoutdinov Room: 158 Endeavour Time: Tuesdays and Thursday 11:30 AM – 12:50 PM

MAR 542 – Fundamentals of Atmosphere and Ocean Dynamics Instructor: Marat Khairoutdinov Room: 158 Endeavour Time: Tuesdays and Thursday 11:30 AM – 12:50 PM Text: Atmosphere, Ocean, and Climate Dynamics: An Introductory Text By John R. Marshall and R. Alan Plumb, Academic Press 2008 This course serves as an introduction to atmosphere and ocean dynamics. It is required of first-year atmospheric science graduate students, and it is recommended for first-year physical oceanography students. It assumes a working knowledge of differential and integral calculus, including partial derivatives and simple differential equations. Its purpose is to prepare students in atmospheric sciences and physical oceanography to move onto more advanced courses in these areas, as well as to acquaint each other with some fundamental aspects of dynamics applied to geophysical fluids outside your area of specialization. It is anticipated that the entire book will be covered. The chapter contents of this text are as follows, but some other topics will also be covered. 1. Characteristics of the atmosphere 2. The global energy balance 3. The vertical structure of the atmosphere 4. Convection 5. The meridional structure of the atmosphere 6. The equations of fluid motion 7. Balanced flow 8. The general circulation of the atmosphere 9. The ocean and its circulation 10. The wind-driven circulation 11. The thermohaline circulation of the ocean 12. Climate and climate variability • !"#$"%"&'"()*"+(,&-.)*/*0-",+--"1-"2*3&4"5$"6,7" • 8+9:";&<*/-"+2&=(">$"%"&'"()*"?+/()0-"-=/'+;*7" • @)*"+<*/+A*":*.()"&'"()*"&;*+9-"1-"+2&=("B"6,7" • !C$"%"&'"()*"?+/()0-"3+9:"1-"19"()*"D&/()*/9"E*,1-.)*/*7" Atmosphere is very thin: 99.9% of mass is below 50 km Compared to the Earth’s radius (6500 km), it is only 1% which is comparable to the thickness of an apple’s skin Thus, the synoptic-scale systems are quasi-two-dimensional! Vertical structure of the atmosphere Pressure (mb) 0.001 0.01 0.1 1 10 100 1000 Permanent vs.