Travel Papers in American Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Questionnaire Responses Emily Bernard

Questionnaire Responses Emily Bernard Modernism/modernity, Volume 20, Number 3, September 2013, pp. 435-436 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2013.0083 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/525154 [ Access provided at 1 Oct 2021 22:28 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] questionnaire responses ments of the productions of the Harlem Renaissance? How is what might be deemed 435 a “multilingual mode of study” vital for our present day work on the movement? The prospect of a center for the study of the Harlem Renaissance is terribly intriguing for future scholarly endeavors. Houston A. Baker is Distinguished University Professor and a professor of English at Vander- bilt University. He has served as president of the Modern Language Association of America and is the author of articles, books, and essays devoted to African American literary criticism and theory. His book Betrayal: How Black Intellectuals Have Abandoned the Ideals of the Civil Rights Era (2008) received an American Book Award for 2009. Emily Bernard How have your ideas about the Harlem Renaissance evolved since you first began writing about it? My ideas about the Harlem Renaissance haven’t changed much in the last twenty years, but they have expanded. I began reading and writing about the Harlem Renais- sance while I was still in college. I was initially drawn to it because of its surfaces—styl- ish people in attractive clothing, the elegant interiors and exteriors of its nightclubs and magazines. Style drew me in, but as I began to read and write more, it wasn’t the style itself but the intriguing degree of importance assigned to the issue of style that kept me interested in the Harlem Renaissance. -

A History of African American Theatre Errol G

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-62472-5 - A History of African American Theatre Errol G. Hill and James V. Hatch Frontmatter More information AHistory of African American Theatre This is the first definitive history of African American theatre. The text embraces awidegeographyinvestigating companies from coast to coast as well as the anglo- phoneCaribbean and African American companies touring Europe, Australia, and Africa. This history represents a catholicity of styles – from African ritual born out of slavery to European forms, from amateur to professional. It covers nearly two and ahalf centuries of black performance and production with issues of gender, class, and race ever in attendance. The volume encompasses aspects of performance such as minstrel, vaudeville, cabaret acts, musicals, and opera. Shows by white playwrights that used black casts, particularly in music and dance, are included, as are produc- tions of western classics and a host of Shakespeare plays. The breadth and vitality of black theatre history, from the individual performance to large-scale company productions, from political nationalism to integration, are conveyed in this volume. errol g. hill was Professor Emeritus at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire before his death in September 2003.Hetaughtat the University of the West Indies and Ibadan University, Nigeria, before taking up a post at Dartmouth in 1968.His publications include The Trinidad Carnival (1972), The Theatre of Black Americans (1980), Shakespeare in Sable (1984), The Jamaican Stage, 1655–1900 (1992), and The Cambridge Guide to African and Caribbean Theatre (with Martin Banham and George Woodyard, 1994); and he was contributing editor of several collections of Caribbean plays. -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

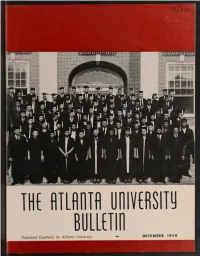

MMilt Published Quarterly by Atlanta University DECEMBER ■ TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 3 Calendar 4 The New Music and Radio Center 6 The Annual Meeting of the As¬ sociation for the Study of Negro Life and History 8 Feature of the Issae French Graduates Lured hy Teaching 12 The 1950 Summer School 13 Sociology Department Con¬ ducts Post Health Survey 13 Private Library Bequeathed to University 14 The Conference on Library Ed¬ ucation AT OPENING OF MUSIC AND RADIO CENTER 17 Charter Day Is Observed (See Page 4) 18 Three Hundred Ninety - to assistant director Eight (Left right) Thomas Bernard, of public relations, RCA Are Enrolled in Graduate Victor; President Rufus E. Clement, of Atlanta Udiversity; James M. Toney, School director of public relations for RCA. 19 Spotlight 20 The Countee Cullen Memorial Collection 22 Graduate Degrees Awarded to 99 at Summer Convocation 23 Sidelines 24 Faculty Items 27 Alumni News 29 Requiescat in Pace 31 A Letter to Alumni and Friends from the President of the University Cover: Summer Graduating Class. 1950 Series III DECEMBER 1950 No. 72 Entered as second-class matter February 28, 1935, at the Post Office at Atlanta, Georgia, under the Act of August 24, 1912. Acceot- ance for mailing at special rate of postage provided for in the Act of February 28, 1925, 538, P. L. 4 H. 2 CALENDAR CHARTER DAY CONVOCATION: October 16 —Dr. Subject: “Integration of Undergraduate Pro¬ Charles S. Johnson. President of Fisk University grams with Graduate Programs in Library Ser¬ Subject: “Coming of Age” vice" CHARTER DAY DINNER: October 16 —Honoring CLOSING OF THE LIBRARY CONFERENCE: No¬ New Members of the Graduate Faculty vember 11 — Summary Delivered by Eric Moore. -

Macleod, Kirsten, Ed. 2018. Carl Van Vechten, the Blind Bow- Boy

144 | Textual Cultures 12.2 (2019) MacLeod, Kirsten, ed. 2018. Carl Van Vechten, The Blind Bow- Boy. Cambridge, UK: Modern Humanities Research Association. Pp. xxviii + 152. ISBN 9781781882900, Paper $17.99. Carl Van Vechten’s The Blind Bow-Boy (1923) is a book about pleasure — about the kinds of pleasure taken by 1920s dandies in literature, per- formance, perfumes, fashion, cocktails, Coney Island, and car rides; about sexual pleasures and the pleasure of solitude; about fads and the short shelf- life of certain kinds of pleasure; about whether one can learn from things that are pleasurable and whether one can learn to take pleasure. It is a modernist novel written in a Decadent register. The cataloguing of inte- riors frequently stands in for character development. The reader comes to understand who people are according to the kinds of tableware with which they surround themselves or in which they are able to find joy. The text speaks in commodity code, mixing the high and the low, mass and high culture, addressing itself to a readership who knows their French literature and avant-garde art and music as well as their fashion houses, perfumiers, and parlor songs. It expects from its audience a deep awareness of literary history as well as an up-to-date savvy concerning bestsellers and modern- ist trends. One is meant to feel whipped about by the whirlwind of things one might enjoy in 1920s New York by visiting certain neighborhoods, booksellers, and beautifully outfitted apartments. In conveying so much detail about the richness of modern pleasure, however, Van Vechten con- structed a novel that demands a certain kind of cultural literacy. -

Archivists & Archives of Color Newsletter

~Archivists & Archives of Color Newsletter~ Newsletter of the Archivists and Archives of Color Roundtable Vol. 19 No. 2 Fall/Winter 2005 Message from the Co-Chair Greetings from the New Editor! By Teresa Mora By Paul Sevilla It was only a few months ago that SAA gathered in New I feel very excited to serve as the new editor of the AAC Orleans for its 69th Annual Meeting. Little did we know at newsletter. One of my goals is to bring to readers articles that the time that the area would soon be devastated by Hurricane are interesting, informative, and inspiring. With help and Katrina. Many of our AAC friends and colleagues were support from my assistant editor, Andrea, we shall ensure that affected by the hurricane that hit the gulf coast. Rebecca this newsletter continues to represent the voices of our diverse Hankins offered family shelter in Texas, and, in an article on membership. the next page, Brenda B. Square at the Amistad Research Center updates us on Tulane’s situation. We have all read I became a member of SAA in my first year as an MLIS reports of the damage, and our thoughts are with all those who student in the Department of Information Studies at UCLA. hail from the area, especially with our colleagues and the As one of the recipients of this year’s Harold T. Pinkett unique collections, which many of us had been so fortunate to Minority Student Award, I had the privilege of attending the just see. conference in New Orleans and meeting the members of AAC. -

Queering Black Greek-Lettered Fraternities, Masculinity and Manhood : a Queer of Color Critique of Institutionality in Higher Education

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2019 Queering black greek-lettered fraternities, masculinity and manhood : a queer of color critique of institutionality in higher education. Antron Demel Mahoney University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Africana Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Higher Education Commons, History of Gender Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mahoney, Antron Demel, "Queering black greek-lettered fraternities, masculinity and manhood : a queer of color critique of institutionality in higher education." (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3286. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3286 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUEERING BLACK GREEK-LETTERED FRATERNITIES, MASCULINITY AND MANHOOD: A QUEER OF COLOR CRITIQUE OF INSTITUTIONALITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION By Antron Demel Mahoney B.S., -

'Poet on Poet': Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes

ANGLOGERMANICA ONLINE 2007. Millanes Vaquero, Mario: ‘Poet on Poet’: Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes (Two Versions for an Aesthetic-Literary Theory) ____________________________________________________________________________________ ‘Poet on Poet’: Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes (Two Versions for an Aesthetic-Literary Theory) Mario Millanes Vaquero, Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Spain) If I am going to be a poet at all, I am going to be POET and not NEGRO POET. Countee Cullen A poet is a human being. Each human being must live within his time, with and for his people, and within the boundaries of his country. Langston Hughes Because the Negro American writer is the bearer of two cultures, he is also the guardian of two literary traditions. Robert Bone Index 1 Introduction 2 Poet on Poet 3 Africa, Friendship, and Gay Voices 4 The (Negro) Poet 5 Conclusions Bibliography 1 Introduction Countee Cullen (1903-1946) and Langston Hughes (1902-1967) were two of the major figures of a movement later known as the Harlem Renaissance. Although both would share the same artistic circle and play an important role in it, Cullen’s reputation was eclipsed by that of Hughes for many years after his death. Fortunately, a number of scholars have begun to clarify their places in literary history. I intend to explain the main aspects in which their creative visions differ: Basically, Cullen’s traditional style and themes, and Hughes’s use of blues, jazz, and vernacular. I will focus on their debut books, Color (1925), and The Weary Blues (1926), respectively. 2 Poet on Poet A review of The Weary Blues appeared in Opportunity on 4 March, 1926. -

James Cummins Bookseller

JAMES CUMMINS BOOKSELLER A Selection of Books to Be Exhibited at the 51st ANNUAL NEW YORK ANTIQUARIAN BOOK FAIR BOOTH E5 APRIL 8-10 Friday noon - 8pm Saturday noon - 7pm Sunday noon - 5pm The Park Avenue Armory 643 Park Avenue, at 67th Street, New York City James Cummins Bookseller • 699 Madison Ave, New York, 10065 • (212) 688-6441 • [email protected] James Cummins Bookseller — Both E5 2011 New York Antiquarian Book Fair 1. (ALBEE, Edward) Van Vechten, Carl. Portrait photograph of Edward Albee. Half-length, seated, in semi- profile. Gelatin silver print. 35 x 23 cm. (approx 14 x 8-3/4 inches), New York: April 18, 1961. Published in Portraits: the Photographs of Carl Van Vechten (1978). Fine. Verso docketed with holograph notations in pencil giving the name of the sitter, date of the photograph, and the the Van Vechten’s reference to negative and print (“VII SS:19”). $2,000 Inscribed by Co-Writer Marshall Brickman 2. [ALLEN, Woody and Marshall Brickman]. Untitled Film Script [Annie Hall]. 120 ff., + 4 ff. appendices. 4to, n.p: [April 15, 1976]. Mechanically reproduced facsimile of Marshall Brickman’s early numbered (#13) screenplay with numerous blue revision pages. Bound with fasteners. Fine. $1,250 With a lengthy INSCRIPTION by co-writer Marshall Brickman. This early version of the script differs considerably from the final shooting version. It is full of asides, flashbacks, gags, and set pieces. It resembles Allen’s earlier screwball comedies and doesn’t fully reflect his turn to a more “serious” kind of filmmaking. Sold to benefit the Writers of America East Foundation and its programs Inscribed by Co-Writer Marshall Brickman 3. -

Advanced September 2005.Indd

Contact: Norman Keyes, Jr. Edgar B. Herwick III Director of Media Relations Press Relations Coordinator 215.684.7862 215.684.7365 [email protected] [email protected] SCHEDULE OF NEW & UPCOMING EXHIBITIONS THROUGH SPRING 2007 This Schedule is updated quarterly. For the latest information please call the Marketing and Public Relations Department NEW AND UPCOMING EXHIBITIONS Looking at Atget September 10–November 27, 2005 Edvard Munch’s Mermaid September 24–December 31, 2005 Jacob van Ruisdael: Dutch Master of Landscape October 23, 2005–February 5, 2006 Beauford Delaney: From New York to Paris November 13, 2005–January 29, 2006 Beauford Delaney in Context: Selections from the Permanent Collection November 13, 2005–February 26, 2006 Gaetano Pesce: Pushing the Limits November 18, 2005–April 9, 2006 Why the Wild Things Are: Personal Demons and Himalayan Protectors November 23, 2005–May 2006 Adventures in a Perfect World: North Indian Narrative Paintings, 1750–1850 November 23, 2005–May 2006 A Natural Attraction: Dutch and Flemish Landscape Prints from Bruegel to Rembrandt December 17, 2005–February 12, 2006 Recent Acquisitions: Prints and Drawings (working title) March 11–May 21, 2006 Andrew Wyeth: Memory and Magic March 29–July 16, 2006 Grace Kelly’s Wedding Dress April 2006 In Pursuit of Genius: Jean-Antoine Houdon and the Sculpted Portraits of Benjamin Franklin May 13–July 30, 2006 Photography at the Julien Levy Gallery (working title) June–September 2006 The Arts in Latin America, 1492--1820 Fall 2006 A Revolution in the Graphic -

AFAM 162 – African American History: from Emancipation to the Present Professor Jonathan Holloway

AFAM 162 – African American History: From Emancipation to the Present Professor Jonathan Holloway Lecture 10 – The New Negroes (continued) IMAGES Photograph of Alain Locke, with inscription to JWJ, June 20, 1926 . Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library; Bibliographic Record Number 39002036001643; Image ID# 3600164. "Aspects of Negro Life: The Negro in an African Setting," by Aaron Douglas (1934). Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Arts and Artifacts Division. "Into Bondage," by Aaron Douglas (1936). Corcoran Gallery of Art/Associated Press; The Evans-Tibbs Collection. "Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery Through Reconstruction," by Aaron Douglas (1934) Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Arts and Artifacts Division. Photograph of Langston Hughes (1925). JWJ MSS 26, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beineck Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Bibliographic Record Number 39002036122787, Image ID# 3612278. Photograph of Charlotte Mason (Date Unknown). Photographs of Blacks, collected chiefly by James Weldon Johnson and Carl Van Vechten, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Bibliographic Record Number 39002041692915, Image ID# 4169291. Photograph of Carl Van Vechten (includes inscription: "To Langston"). Photograph of Fredi Washington (wearing armband protesting lynching). Morgan and Marvin Smith (M & M Smith Studio) ca. 1938. Photograph of Mary McLeod Bethune, by Carl Van Vechten (6-Apr-49). Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library; Call Number JWJ Van Vechten; Bibliographic Record Number 2001889. Drawing to advertise Carl Van Vechten's book, Nigger Heaven, by Aaron Douglas. Beinecke; Call Number Art Object 1980.180.2; Bibliographic Record Number 39002035069476; Image ID# 3506947.