African American Modernist Lynching Drama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia Douglas Johnson and Eulalie Spence As Figures Who Fostered Community in the Midst of Debate

Art versus Propaganda?: Georgia Douglas Johnson and Eulalie Spence as Figures who Fostered Community in the Midst of Debate Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Caroline Roberta Hill, B.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2019 Thesis Committee: Jennifer Schlueter, Adviser Beth Kattelman Copyright by Caroline Roberta Hill 2019 Abstract The Harlem Renaissance and New Negro Movement is a well-documented period in which artistic output by the black community in Harlem, New York, and beyond, surged. On the heels of Reconstruction, a generation of black artists and intellectuals—often the first in their families born after the thirteenth amendment—spearheaded the movement. Using art as a means by which to comprehend and to reclaim aspects of their identity which had been stolen during the Middle Passage, these artists were also living in a time marked by the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and segregation. It stands to reason, then, that the work that has survived from this period is often rife with political and personal motivations. Male figureheads of the movement are often remembered for their divisive debate as to whether or not black art should be politically charged. The public debates between men like W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke often overshadow the actual artistic outputs, many of which are relegated to relative obscurity. Black female artists in particular are overshadowed by their male peers despite their significant interventions. Two pioneers of this period, Georgia Douglas Johnson (1880-1966) and Eulalie Spence (1894-1981), will be the subject of my thesis. -

Questionnaire Responses Emily Bernard

Questionnaire Responses Emily Bernard Modernism/modernity, Volume 20, Number 3, September 2013, pp. 435-436 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2013.0083 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/525154 [ Access provided at 1 Oct 2021 22:28 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] questionnaire responses ments of the productions of the Harlem Renaissance? How is what might be deemed 435 a “multilingual mode of study” vital for our present day work on the movement? The prospect of a center for the study of the Harlem Renaissance is terribly intriguing for future scholarly endeavors. Houston A. Baker is Distinguished University Professor and a professor of English at Vander- bilt University. He has served as president of the Modern Language Association of America and is the author of articles, books, and essays devoted to African American literary criticism and theory. His book Betrayal: How Black Intellectuals Have Abandoned the Ideals of the Civil Rights Era (2008) received an American Book Award for 2009. Emily Bernard How have your ideas about the Harlem Renaissance evolved since you first began writing about it? My ideas about the Harlem Renaissance haven’t changed much in the last twenty years, but they have expanded. I began reading and writing about the Harlem Renais- sance while I was still in college. I was initially drawn to it because of its surfaces—styl- ish people in attractive clothing, the elegant interiors and exteriors of its nightclubs and magazines. Style drew me in, but as I began to read and write more, it wasn’t the style itself but the intriguing degree of importance assigned to the issue of style that kept me interested in the Harlem Renaissance. -

The New Negro Arts and Letters Movement Among Black University Students in the Midwest, 1914~1940

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Black Studies Faculty Publications Department of Black Studies 2004 The ewN Negro Arts and Letters Movement Among Black University Students in the Midwest, 1914-1940 Richard M. Breaux University of Nebraska at Omaha, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/blackstudfacpub Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Breaux, Richard M., "The eN w Negro Arts and Letters Movement Among Black University Students in the Midwest, 1914-1940" (2004). Black Studies Faculty Publications. 1. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/blackstudfacpub/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Black Studies at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Black Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW NEGRO ARTS AND LETTERS MOVEMENT AMONG BLACK UNIVERSITY STUDENTS IN THE MIDWEST, 1914~1940 RICHARD M. BREAUX The 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s were an excit~ and underexplored. 1 This article explores the ing time for black artists and writers in the influence of the New Negro arts and letters United States. Much of the historical litera~ movement on black students at four mid~ ture highlights the so~called Harlem Renais~ western state universities from 1914 to 1940. sance or its successor, the Black Chicago Black students on white midwestern cam~ Renaissance. Few studies, however, document puses like the University of Kansas (KU), Uni~ the influence of these artistic movements out~ versity of Iowa (UI), University of Nebraska side major urban cities such as New York, (UNL), and University of Minnesota (UMN) Chicago, or Washington, DC. -

A History of African American Theatre Errol G

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-62472-5 - A History of African American Theatre Errol G. Hill and James V. Hatch Frontmatter More information AHistory of African American Theatre This is the first definitive history of African American theatre. The text embraces awidegeographyinvestigating companies from coast to coast as well as the anglo- phoneCaribbean and African American companies touring Europe, Australia, and Africa. This history represents a catholicity of styles – from African ritual born out of slavery to European forms, from amateur to professional. It covers nearly two and ahalf centuries of black performance and production with issues of gender, class, and race ever in attendance. The volume encompasses aspects of performance such as minstrel, vaudeville, cabaret acts, musicals, and opera. Shows by white playwrights that used black casts, particularly in music and dance, are included, as are produc- tions of western classics and a host of Shakespeare plays. The breadth and vitality of black theatre history, from the individual performance to large-scale company productions, from political nationalism to integration, are conveyed in this volume. errol g. hill was Professor Emeritus at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire before his death in September 2003.Hetaughtat the University of the West Indies and Ibadan University, Nigeria, before taking up a post at Dartmouth in 1968.His publications include The Trinidad Carnival (1972), The Theatre of Black Americans (1980), Shakespeare in Sable (1984), The Jamaican Stage, 1655–1900 (1992), and The Cambridge Guide to African and Caribbean Theatre (with Martin Banham and George Woodyard, 1994); and he was contributing editor of several collections of Caribbean plays. -

HARLEM in SHAKESPEARE and SHAKESPEARE in HARLEM: the SONNETS of CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, and GWENDOLYN BROOKS David J

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2015 HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS David J. Leitner Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Leitner, David J., "HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS" (2015). Dissertations. Paper 1012. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS by David Leitner B.A., University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana, 1999 M.A., Southern Illinois University Carbondale, 2005 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Department of English in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2015 DISSERTATION APPROVAL HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS By David Leitner A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Approved by: Edward Brunner, Chair Robert Fox Mary Ellen Lamb Novotny Lawrence Ryan Netzley Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 10, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF DAVID LEITNER, for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in ENGLISH, presented on April 10, 2015, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

Black History, 1877-1954

THE BRITISH LIBRARY AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND LIFE: 1877-1954 A SELECTIVE GUIDE TO MATERIALS IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY BY JEAN KEMBLE THE ECCLES CENTRE FOR AMERICAN STUDIES AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND LIFE, 1877-1954 Contents Introduction Agriculture Art & Photography Civil Rights Crime and Punishment Demography Du Bois, W.E.B. Economics Education Entertainment – Film, Radio, Theatre Family Folklore Freemasonry Marcus Garvey General Great Depression/New Deal Great Migration Health & Medicine Historiography Ku Klux Klan Law Leadership Libraries Lynching & Violence Military NAACP National Urban League Philanthropy Politics Press Race Relations & ‘The Negro Question’ Religion Riots & Protests Sport Transport Tuskegee Institute Urban Life Booker T. Washington West Women Work & Unions World Wars States Alabama Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut District of Columbia Florida Georgia Illinois Indiana Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Nebraska Nevada New Jersey New York North Carolina Ohio Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania South Carolina Tennessee Texas Virginia Washington West Virginia Wisconsin Wyoming Bibliographies/Reference works Introduction Since the civil rights movement of the 1960s, African American history, once the preserve of a few dedicated individuals, has experienced an expansion unprecedented in historical research. The effect of this on-going, scholarly ‘explosion’, in which both black and white historians are actively engaged, is both manifold and wide-reaching for in illuminating myriad aspects of African American life and culture from the colonial period to the very recent past it is simultaneously, and inevitably, enriching our understanding of the entire fabric of American social, economic, cultural and political history. Perhaps not surprisingly the depth and breadth of coverage received by particular topics and time-periods has so far been uneven. -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

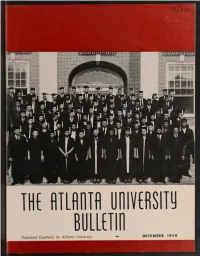

MMilt Published Quarterly by Atlanta University DECEMBER ■ TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 3 Calendar 4 The New Music and Radio Center 6 The Annual Meeting of the As¬ sociation for the Study of Negro Life and History 8 Feature of the Issae French Graduates Lured hy Teaching 12 The 1950 Summer School 13 Sociology Department Con¬ ducts Post Health Survey 13 Private Library Bequeathed to University 14 The Conference on Library Ed¬ ucation AT OPENING OF MUSIC AND RADIO CENTER 17 Charter Day Is Observed (See Page 4) 18 Three Hundred Ninety - to assistant director Eight (Left right) Thomas Bernard, of public relations, RCA Are Enrolled in Graduate Victor; President Rufus E. Clement, of Atlanta Udiversity; James M. Toney, School director of public relations for RCA. 19 Spotlight 20 The Countee Cullen Memorial Collection 22 Graduate Degrees Awarded to 99 at Summer Convocation 23 Sidelines 24 Faculty Items 27 Alumni News 29 Requiescat in Pace 31 A Letter to Alumni and Friends from the President of the University Cover: Summer Graduating Class. 1950 Series III DECEMBER 1950 No. 72 Entered as second-class matter February 28, 1935, at the Post Office at Atlanta, Georgia, under the Act of August 24, 1912. Acceot- ance for mailing at special rate of postage provided for in the Act of February 28, 1925, 538, P. L. 4 H. 2 CALENDAR CHARTER DAY CONVOCATION: October 16 —Dr. Subject: “Integration of Undergraduate Pro¬ Charles S. Johnson. President of Fisk University grams with Graduate Programs in Library Ser¬ Subject: “Coming of Age” vice" CHARTER DAY DINNER: October 16 —Honoring CLOSING OF THE LIBRARY CONFERENCE: No¬ New Members of the Graduate Faculty vember 11 — Summary Delivered by Eric Moore. -

Aneta Pawłowska Department of Art History, University of Łódź [email protected]

Art Inquiry. Recherches sur les arts 2014, vol. XVI ISSN 1641-9278 Aneta Pawłowska Department of Art History, University of Łódź [email protected] THE AMBIVALENCE OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN1 CULTURE. THE NEW NEGRO ART IN THE INTERWAR PERIOD Abstract: Reflecting on the issue of marginalization in art, it is difficult not to remember of the controversy which surrounds African-American Art. In the colonial period and during the formation of the American national identity this art was discarded along with the entire African cultural legacy and it has emerged as an important issue only at the dawn of the twentieth century, along with the European fashion for “Black Africa,” complemented by the fascination with jazz in the United States of America. The first time that African-American artists as a group became central to American visual art and literature was during what is now called the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s. Another name for the Harlem Renaissance was the New Negro Movement, adopting the term “New Negro”, coined in 1925 by Alain Leroy Locke. These terms conveyed the belief that African-Americans could now cast off their heritage of servitude and define for themselves what it meant to be an African- American. The Harlem Renaissance saw a veritable explosion of creative activity from the African-Americans in many fields, including art, literature, and philosophy. The leading black artists in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940 were Archibald Motley, Palmer Hayden, Aaron Douglas, Hale Aspacio Woodruff, and James Van Der Zee. Keywords: African-American – “New Negro” – “Harlem Renaissance” – Photography – “African Art” – Murals – 20th century – Painting. -

Travel Papers in American Literature

ROAD SHOW Travel Papers in American Literature This exhibition celebrates the American love of travel and adventure in both literary works and the real-life journeys that have inspired our most beloved travel narratives. Exploring American literary archives as well as printed and published works, Road Show reveals how travel is recorded, marked, and documented in Beinecke Library’s American collections. Passports and visas, postcards and letters, travel guides and lan- guage lessons—these and other archival documents attest to the physical, emotional, and intellectual experiences of moving through unfamiliar places, encountering new landscapes and people, and exploring different ways of life and world views. Literary manuscripts, travelers’ notebooks, and recorded reminiscences allow us to consider and explore travel’s capacity for activating the imagination and igniting creativity. Artworks, photographs, and published books provide opportunities to consider the many ways artists and writers transform their own activities and human interactions on the road into works of art that both document and generate an aesthetic experience of journeying. 1-2 Luggage tag, 1934, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers 3 Langston Hughes, Mexico, undated, Langston Hughes Papers 4 Shipboard photograph of Margaret Anderson, Louise Davidson, Madame Georgette LeBlanc, undated, Elizabeth Jenks Clark Collection of Margaret Anderson 5-6 Langston Hughes, Some Travels of Langston Hughes world map, 1924-60, Langston Hughes Papers 7 Ezra Pound, Letter to Viola Baxter Jordan with map, 1949, Viola Baxter Jordan Papers 8 Kathryn Hulme, How’s the Road? San Francisco: Privately Printed [Jonck & Seeger], 1928 9 Baedeker Handbooks for Greece, Belgium and Holland, Paris, Berlin, Great Britain, various dates 10 H. -

Art for Whose Sake?: Defining African American Literature

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies Summer 7-17-2012 Art for whose Sake?: Defining African American Literature Ebony Z. Gibson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Gibson, Ebony Z., "Art for whose Sake?: Defining African American Literature." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/17 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ART FOR WHOSE SAKE?: DEFINING AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE by EBONY Z. GIBSON Under the Direction of Jonathan Gayles ABSTRACT This exploratory qualitative study describes the criteria that African American Literature professors use in defining what is African American Literature. Maulana Karenga’s black arts framework shaped the debates in the literature review and the interview protocol; furthermore, the presence or absence of the framework’s characteristics were discussed in the data analysis. The population sampled was African American Literature professors in the United States who have no less than five years experience. The primary source of data collection was in-depth interviewing. Data analysis involved open coding and axial coding. General conclusions include: (1) The core of the African American Literature definition is the black writer representing the black experience but the canon is expanding and becoming more inclusive. (2) While African American Literature is often a tool for empowerment, a wide scope is used in defining methods of empowerment.