Antrocom Journal of Anthropology ANTROCOM Journal Homepage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angami Nagas

Angami Nagas Duration: 6 Nights / 7 Days Destinations: Guwahati - Kaziranga - Kohima - Touphema - Dimori Cove - Khonoma - Dimapur Day 01: Arrival at Guwahati After you come to Guwahati, go to the hotel and stay there. Spend the night at Guwahati. Day 02: Guwahati - Kaziranga National Park Go to the Kamakhya Temple, which is renowned site of pilgrimage for the people of the Hindu community. More than a million devotees flock the temple on the ritual of Ambubashi. Come back to the hotel and relax. After some time, go on driving trips to the Kaziranga National park. It is around 220 kms away. Stay at the jungle resort after you arrive. Visit the local tea plantations in the afternoon. Day 03: Kaziranga Go to the central range of the Kaziranga National Park in the early hours of morning. After you return, spend some time in lunch and go to the western range on jeep safari. Spend the night in the hotel. Stay the night at Kaziranga. Day 04: Kaziranga - Kohima - Touphema Tourist Village From Kaziranga, go to Kohima. It is the capital city of Nagaland is known for its scenic beauty. After you land at the city, go to the Touphema Village Resort. It is around 41 kms from Kohima. The resort is managed by the Angami Naga village community. Get a feel of the rich culture and heritage by going to the village and also enjoy village cultural programs. Stay for the night at the Touphema Tourist village. Day 05: Touphema - Kohima - Dimori Cove Early in the morning, go to the village and visit the points of interest. -

Directory Establishment

DIRECTORY ESTABLISHMENT SECTOR :RURAL STATE : NAGALAND DISTRICT : Dimapur Year of start of Employment Sl No Name of Establishment Address / Telephone / Fax / E-mail Operation Class (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) NIC 2004 : 0121-Farming of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, asses, mules and hinnies; dairy farming [includes stud farming and the provision of feed lot services for such animals] 1 STATE CATTLE BREEDING FARM MEDZIPHEMA TOWN DISTRICT DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797106, STD CODE: 03862, 1965 10 - 50 TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 0122-Other animal farming; production of animal products n.e.c. 2 STATE CHICK REPARING CENTRE MEDZIPHEMA TOWN DISTRICT DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797106, STD CODE: 03862, TEL 1965 10 - 50 NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 3610-Manufacture of furniture 3 MS MACHANIDED WOODEN FURNITURE DELAI ROAD NEW INDUSTRIAL ESTATE DISTT. DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD 1998 10 - 50 UNIT CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 4 FURNITURE HOUSE LEMSENBA AO VILLAGE KASHIRAM AO SECTOR DISTT. DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD CODE: 2002 10 - 50 NA , TEL NO: 332936, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 5220-Retail sale of food, beverages and tobacco in specialized stores 5 VEGETABLE SHED PIPHEMA STATION DISTT. DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA 10 - 50 NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 5239-Other retail sale in specialized stores 6 NAGALAND PLASTIC PRODUCT INDUSTRIAL ESTATE OLD COMPLEX DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD CODE: NA , 1983 10 - 50 TEL NO: 226195, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. -

Cultural Politics of Hornbill Festival, Nagaland

Prohibition and Naga Cultural Identity: Cultural Politics of Hornbill Festival, Nagaland Theyiesinuo Keditsu Abstract This paper explores the conflict between two important markers of Naga cultural identity namely ethnic identity and Christian identity, brought about by the observance of the Hornbill Festival in Kohima, Nagaland. In particular, it examines the ways in which the hegemony of the church via the long-standing prohibition of alcohol is contested in the space of Kisama, the venue for the Hornbill festival and during week to ten day long celebration of the festival. It proposes that by making these contestations possible, the Hornbill festival has given rise to new possibilities for the articulation of Naga cultural identity. Keywords: Naga cultural identity, Ethnic identity, Christian identity, Prohibition, Hornbill Festival The Hornbill Festival was created and implemented by the Government of Nagaland in 2000. The first staging of the Hornbill Festival occurred in the Kohima Local Ground, which is situated in the heart of Kohima Town. In 2003, it was moved to its now permanent location, at Kisama, a heritage village constructed as the venue for this festival. It is held on the first week of December of every year. Volume 2. Issue 2. 2014 22 URL: http://subversions.tiss.edu/ This paper is based on fieldwork carried out between 2008 to 2011 in Kohima, Nagaland, particularly during the first week of December when the Hornbill festival is held. Data was collected through qualitative methods such as in-depth interviews, focus group discussion and participant observation. It is also partly a product of my own negotiations of my ethnic identity as an Angami Naga and as a practising Baptist and therefore member of the Baptist Church of Nagaland. -

PROFILE Name Designation : Professor in Education Date Of

PROFILE Name : Prof Buno Liegise Designation : Professor in Education Date of Joining : 18.08.94 as lecturer under NEHU Email ID : [email protected] [email protected] Contact No. : +91 9436011041 Specialization/Area of Interest: Creativity and Education, Sociology of Education, Educational Psychology, Teacher Education , Gender Studies, Research Methods Educational qualification : Examination Passed Div with % Subject Year Board/University 1. HSLC 1st 63.88 HSLC 1980 NBSE 2. PU Arts 2nd 57.11 Arts 1982 NEHU 3. BA Honours 2nd 56.5 Education 1985 NBU (Silver Medal) 4. MA 1st 62.75 Education 1987 NEHU 5. MPhil 1st 60.1 Education 1989 DU 6. PhD Awarded Education 1996 JNU 7. NET Qualified Education 1991 UGC Research Degrees University Year of Award Title of Thesis 1.Jawaharlal Nehru University October, 1996 Institutional Climate, Achievement Motivation, Academic Achievement of High School Students in Nagaland 2.Delhi University June, 1990 A Critical Review of some Creativity Studies in Indian Schools Teaching Experience University Number of Years Nagaland University 24 years of teaching at the Post- Graduate, M.Phil and Ph.D levels, from 19 August 1994 till date. Professional Career Position held Institution Period Dean, Students' Welfare, Nagaland University 2003-2006 Kohima Campus Head, Dept of Education, Nagaland University 2009-2012 Kohima Campus Director i/c, Women's Studies Nagaland University 2012-2014 Centre Dean, School of Humanities and Nagaland University 2014-2017 Education Academic and Administration Nagaland University 8th September 2016 - June i/c, Kohima Campus 2017 Head i/c, Dept of Education Nagaland University June 2018- ACADEMIC AND RESEARCH CONTRIBUTION A) Journal publications Sl. -

NAGALAND (KOHIMA – 120 PAX) Day – 1 (20.12.2014, Saturday

NAGALAND (KOHIMA – 120 PAX) Day – 1 (20.12.2014, Saturday) : ARRIVE AT GUWAHATI RAILWAY STATION – KOHIMA (12Hrs.) Meet and greet on arrival at Guwahati Railway Station at 1700 hrs. Proceed at night towards Kohima reach Kohima at around 0800hrs on 21.12.2014. Day –2 (21.12.2014, Sunday) : KOHIMA - KHONOMA - KOHIMA (20 KMS / 1 HR) After check-in and after breakfast, explore Kohima and its surroundings. Visit local market where you will find all kinds of worms and insects being sold at the market by the local people. Visit Second World War cemetery where thousands lie there remembered. Further drive to Kisama, the heritage village where the annual Hornbill festival takes place. Visit different morungs of the Nagas and the war Museum. Lunch enroute/hotel. Next visit Kigwema village and Jakhama village to see rich men houses, morungs, etc. Drive back to Kohima, Visit State Museum. Diner and overnight at Kohima Hotel. History & Tradition Day – 3 (22.12.2014, Monday): KOHIMA After breakfast drive to the legendary village Khonoma. Visit Grover’s memorial at Jotsoma village. On reaching Khonoma, explore the village. Khonoma became the first Green Village in India when the village community decided to stop hunting, logging and forest fire. Khonoma was also known for her valor and prowess in those days of war. At Khonoma visit G. H. Damant Memorial, the first British political officer to the Naga hills, visit morungs, cairn circles, age group houses, ceremonial gates, etc. Drive to the buffer zone of Khonoma Nature Conservation and Tragopan Sanctuary. PICNIC LUNCH!! See the state animal Mithun (Bos Frontalis) and feed them with salt. -

Nagaland Kohima District

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES - 15 ; NAGALAND DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XIII-A VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY PART XllI-B VILLAGE & TOWN PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT AND SCHEDULED TRIBES PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT KOHIMA DISTRICT DANIEL KENT of the Indian Frontier Administrative Service DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERA nONS NAGALAND 1981 CENSUS List of Publications, Nagaland. (All the pUblications of this state will bear series No. 15) SI. Part No. ! Subje~t Remarks 1 I 2 3 4 CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATION 1. Part I Administration report For office use 2. Part II-A General Population Tables ( A-series Tables) Not yet Part H·B General Population Tables (Primary Cens'ls Abstract) , - . , Published 3. Part III General Economic Tables Not yet Pllblished 4. Part IV Social & Cultural Tables Not yet Published 5. ·Part V Migration Tables Not yet Published 6. Part VI Fertility Tables Not yet Published 7. .Part VII Tables on houses and disabled population Not yet (Tables H·I to H-2J Published 8. Part VIII Household Tables Not yet (Tables HH·1 to HH.16) Published Household Tables (Tables HH-17 to RH-l? S,C. HH-S.T.) 9. Part IX SPL. Tables on S.C,fS.T. Not yet (Tables S.T.·1 to 8.T.·9) Published 10. Part X-A Town Directory I Part x-a Survey reports on Villages and Towns I Part X·C Survey reports on selected Villages Not yet 11. Part XI Enthrographic notes and special studies I Published I on S.C. and S.T. J 12. Part XU Census Atlas i! STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATION 13. -

ISSN: 2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 5(10), 232-243

ISSN: 2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 5(10), 232-243 Journal Homepage: - www.journalijar.com Article DOI: 10.21474/IJAR01/5526 DOI URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/5526 RESEARCH ARTICLE GRANULOMETRIC ANALYSIS AND PALAEOENVIRONMENTAL RECONSTRUCTION OF THE PALAEOGENE DISANG –BARAIL TRANSITIONAL SEQUENCE IN PARTS OF KOHIMA SYNCLINORIUM, NAGA HILLS, NE INDIA. Lily Sema1 and *Nagendra Pandey2. 1. Department of Geology, Kohima Science College (Aut), Jotsoma, Nagaland. 2. Department of Earth Science, Assam University, Silchar. …………………………………………………………………………………………………….... Manuscript Info Abstract ……………………. ……………………………………………………………… Manuscript History The Palaeogene Disang – Barail Transitional Sequence (DBTS) cropping at the tip of the Kohima Synclinorium, Naga Hills has been Received: 03 August 2017 analyzed for its grain – size characteristics and their interpretations in Final Accepted: 05 September 2017 terms of environmental processes. Besides graphical and statistical Published: October 2017 parameters; attempts have also been made to analyze the size – data Key words:- using multigroup discriminant function after Sahu (1983). The grain- Disang-Barail Transitional Sequence size frequency distribution, descriptive statistical parameters, nature of (DBTS), Kohima Synclinorium, Naga Cummulative curves and the multigroup discriminant function analyses Hills, Granulometric analysis, including V1 – V2 plot, all indicate that the DBTS correspond Palaeoenvironmental reconstruction. approximately to turbidity deposits. Copy Right, IJAR, 2017,. All -

Mysteries of Nagaland

Nagaland is one of India’s most beautiful states. Sometimes referred to as the Switzerland of the east, it is a land of rolling hills and lush valleys. Nagaland is engulfed in mystery, inhabited by vibrant people each fiercely proud of their identity. Folklore still abounds, with stories passed down from generation to generation and music is an integral part of their life. On this journey, we will appreciate a pocket of India that is so rarely experienced. This land of proud warriors, weavers and green pristine hills is like a chapter that one always wants to read again and again. Our journey is calling you to come unravel its mysteries and explore a different way of life. I T I N E R A R Y Day 1- 19 April (Mon): Dimapur Arrival – Kohima (L,D) All arrivals to reach Dimapur between 1300 – 1400 hours. On arrival, we will have lunch in Dimapur and then head to Kohima (approx. 3 hours) You will be booked at the Hotel Vivor or similar. Check in and relax. Dinner and overnight at the hotel Day 2- 20 April (Tue): Kohima (B,L,D) This morning, after a leisurely breakfast we will drive an hour away to do the Mount Pulie Badze trek. This hour long trek offers breath-taking views overlooking the city of Kohima. At the top, we will enjoy a lovely picnic lunch and take in some fresh air in scenic surroundings. We will then return to Kohima and in the early evening we will visit the local market. This is the main market in Kohima (open air) selling vegetables, indigenous tools, fruits etc. -

Kohima Ambulance Distribution

Kohima Ambulance Ambulance Jurisdiction Contact No. Driver Name & Sl. Ambulance Allotted to Name of the Block of Health Contact No. No Regd.No Health Units PHC SC Units 1. NL-10-7602 Chiephobozou Chiephobozou Zhadima PHC Chiephobozou Dr Nyan Kikon Kevichalhou CHC Block Nerhe Model 9436010127 9612799293 Nerhema Phezha Chiechama Nachama Zhadima Phekherkiema Bawe Phekherkiema Basa Ziezou Viphoma Tsiesema Bawe Tsiesema Basa NL-10-6836 Botsa PHC Tuophema PHC Botsa Dr Adi Belho Tseimekhu Bawe 9436438409 Tseimekhu Basa Teichuma Seiyhama Bawe Seiyhama Phesa Tuophema Tuophe Phezou 2. NL-10-6856 Viswema CHC Viswema Block Viswema Dr Rüütuoü Vizasel Khuzama Sorhie 9436607672 Jakhama PHC Jakhama 9436212799 Kigwema Kimipfupfe PHC Mima Mitelephe Pfuchama Phesama 3. NL-10-7590 Kezocha PHC Kezoma Dr Asano Temjen Vichazouma Sophie 9436650637 Dihoma 9436000906 Kezo Town Kezo Basa Kidima Kejumetouma Bawe Kejumetouma Basa 4. Sechu Block Sechu PHC Sechu Zubza Sechuma Peducha Kiruphe Bawe Kiruphe Basa Mengujuma Mezoma PHC Mezoma Mezo Basa Jotsoma PHC Jotsoma Seithogei Sc. College Khonoma PHC Khonoma Dzulekie 5. NL-10-8167 Tseminyu CHC Tseminyu Block Tseminyu Village Dr Runolo T.Zisunyu Kekhrieneizo 9615002865 Tseminyu old town Peseyie Zumpha 9436077411 Terogvunyu Khonibinzun Kashanyu Kashanyishun New Terogvunyu Henbenji Ngvuphen Tseminyu New Town Rengmapani Rumensinyu Likhwenchu Phenshunyu Khenyu Phenwhenyu Tseminyu South Village Sendenyu Old Sendenyu New Thongsu Tsosinyu Logwasinyu 6. NL-10-7589 Chunlikha PHC Chunlikha PHC Nsunyu Dr Thomas Joel Chunlikha Keppen -

Faculty Profile

FACULTY PROFILE 1. Name: DR. DITAMULÜ VASA 2. Designation: Assistant Professor (Archaeology) 3. Department: Department of History & Archaeology Nagaland University, Kohima Campus, Meriema. Kohima-797004, Nagaland. Email: [email protected] Ph No: +91 9402868628 4. Professional experience & Year of joining: Teaching & Research (1997 to date) Department of History & Archaeology Nagaland University, Kohima Campus, Meriema. 5. Education: • B.Sc.: Anthropology (Hons.), Kohima Science College, Jotsoma, North Eastern Hill University. • M.A: Department of Archaeology, Deccan College (Post-Graduate & Research Institute), Pune. • UGC NET (Archaeology) • PhD: Department of Archaeology, Deccan College (Post-Graduate & Research Institute), Pune Title of Thesis: Traditional Ceramics Among the Nagas: An Ethnoarchaeological Perspective (2011). 6. Professional Society Memberships: • Indian Society for Pre-historic & Quaternary Studies (ISPQS) • North East India History Association (NEIHA) • Anthropological Society of Nagaland (ASN) 7. Projects completed & On-going: • 2007: Pottery traditions among the Chakhesang and the Pochury Nagas, under the project on “Dying and Vanishing Art of Northeast India” funded by North East Zone Cultural Centre, Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India. 1 • 2007-08: Archaeological Investigation at Chungliyimti, Tuensang District, Nagaland as part of the Major Research Theme Cultural History, Ethnography and Physical Characteristics of the Nagas of Nagaland, a joint undertaking of the Anthropological Society of Nagaland (ASN) and Directorate of Art & Culture, Govt. of Nagaland (Phase-I). • 2010: Bark Weaving Tradition: Traditional weaving craft of the Khiamniungan Naga Tribe under the project on “Dying and Vanishing Art of Northeast India” funded by North East Zone Cultural Centre, Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India. • 2012: Carnelian Crafts of South Asia – Studies on Social System supporting the ‘Tradition’. -

5 August September with Cover

Sharing: February - March 2017 1 Sharing: February - March 2017 2 Message from the Shepherd Dear Friends, We are in the year 2017, a year with hopes and anxieties, challenges and opportunities. We do not know what awaits us during the year ahead. We as Christians are always assured of Lord’s presence, guidance and inspiration. He prompts us with the assurance of faith. “Do not fear, for I am with you; do not be dismayed, for I am your God. I will strengthen you and help you; I will uphold you with my righteous right hand.” (Isaiah 41:10). Whether we are swayed and moved by the Trump influence or Modi decisions, difference and diffidence in our state or local politics, let us trust in the Lord of history and make the challenges we face as an opportunities to come closer to the Lord and become more intimate with the Lord of history who guides the destiny of nations and individuals. “Do not be anxious about anything, but in every situation, by prayer and petition, with thanksgiving, present your requests to God. And the peace of God, which transcends all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus.” (Philippians 4:6-7). These days we are also facing problems related to the Municipal elections and subsequent polarization among peoples. It is important that the issues connected with it must be studied in its entirety and with an open attitude and mindset in tune with the changing time, keeping in mind the preservation of traditional values without compromising progress and prospect for growth and development. -

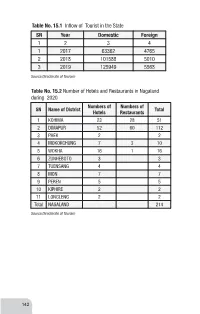

SN Year Domestic Foreign 1 2 3 4 1 2017 63362 4765 2 2018 101588 5010 3 2019 125949 5568

Table No. 15.1 Inflow of Tourist in the State SN Year Domestic Foreign 1 2 3 4 1 2017 63362 4765 2 2018 101588 5010 3 2019 125949 5568 Source:Directorate of Tourism Table No. 15.2 Number of Hotels and Restaurants in Nagaland during 2020 Numbers of Numbers of SN Name of District Total Hotels Restaurants 1 KOHIMA 23 28 51 2 DIMAPUR 52 60 112 3 PHEK 2 2 4 MOKOKCHUNG 7 3 10 5 WOKHA 16 1 16 6 ZUNHEBOTO 3 3 7 TUENSANG 4 4 8 MON 7 7 9 PEREN 5 5 10 KIPHIRE 2 2 11 LONGLENG 2 2 Total NAGALAND 214 Source:Directorate of Tourism 142 Table No. 15.3 Tourist Villages in Nagaland during 2020 SN Name of Tourist Village District 1 2 3 1 Khonoma Kohima 2 Touphema Kohima 3 Benreu New Peren 4 Riphiym/Doyang Wokha 5 Nlongidang Wokha 6 Changtongya Mokokchung 7 Chuchuyimlanng Mokokchung 8 Mopungchukit Mokokchung 9 Longjang Mokokchung 10 Longsa Mokokchung 11 Sungratsu Mokokchung 12 Pilgrimage Village Molungyimsen Mokokchung 13 Phek village Phek 14 Leshemi Phek 15 Thetsumi Phek 16 Chesezu Phek 17 Matikhru Phek 18 Satoi Zunheboto 19 Ghukhiye Zunheboto 20 Aizuto Zunheboto 21 Chui Mon 22 Longwa Mon 23 Ungma Mokokchung 24 Khezhakeno Phek 25 Phesachodu Phek 26 Diezephe craft village Dimapur 27 Thanamir Kiphire 28 Longkhum Mokokchung 29 Pangti village Wokha 30 Yikhum Wokha Source:Directorate of Tourism 143 Table No. 15.4 Tourist Spot in Nagaland during 2020 SN Name of Tourist SPOT District 1 Dzukou Valley Kohima 2 Mt.Japfu peak Kohima 3 Kisama Kohima 4 Governor’s camp Liphayan Wokha 5 shiloi lake Phek 6 Fakim wild life sanctuary Kiphire 7 Shangnyu Mon 8 Mt.Tiyi Wokha