Bojana Complete Thesis 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muzikološki Zbornik Musicological Annual Xliii

MUZIKOLOŠKI ZBORNIK MUSICOLOGICAL ANNUAL X L I I I / 2 ZVEZEK/VOLUME L J U B L J A N A 2 0 0 7 RACIONALIZEM MAGIČNEGA NADIHA: GLASBA KOT PODOBA NEPOJMOVNEGA SPOZNAVANJA RATIONALISM OF A MAGIC TINGE: MUSIC AS A FORM OF ABSTRACT PERCEPTION Zbornik ob jubileju Marije Bergamo Izdaja • Published by Oddelek za muzikologijo Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani Urednik zvezka • Edited by Leon Stefanija (Ljubljana) • Katarina Bogunović Hočevar (Ljubljana) Urednik • Editor Matjaž Barbo (Ljubljana) Asistent uredništva • Assistant Editor Jernej Weiss (Ljubljana) Uredniški odbor • Editorial Board Mikuláš Bek (Brno) Jean-Marc Chouvel (Reims) David Hiley (Regensburg) Nikša Gligo (Zagreb) Aleš Nagode (Ljubljana) Niall O’Loughlin (Loughborough) Leon Stefanija (Ljubljana) Andrej Rijavec (Ljubljana), častni urednik • honorary editor Uredništvo • Editorial Address Oddelek za muzikologijo Filozofska fakulteta Aškerčeva 2, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenija e-mail: [email protected] http://www.ff.uni-lj.si Prevajanje • Translation Neville Hall Cena • Price 10,43 € (2500 SIT) / 20 € (other countries) Tisk • Printed by Birografika Bori d.o.o., Ljubljana Naklada 500 izvodov • Printed in 500 copies Rokopise, publikacije za recenzije, korespondenco in naročila pošljite na naslov izdajatelja. Prispevki naj bodo opremljeni s kratkim povzetkom (200–300 besed), izvlečkom (do 50 besed), ključnimi besedami in kratkimi podatki o avtorju. Nenaročenih rokopisov ne vračamo. Manuscripts, publications for review, correspondence and annual subscription rates should -

Bauhaus Networking Ideas and Practice NETWORKING IDEAS and PRACTICE Impressum

Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb Zagreb, 2015 Bauhaus networking ideas and practice NETWORKING IDEAS AND PRACTICE Impressum Proofreading Vesna Meštrić Jadranka Vinterhalter Catalogue Bauhaus – Photographs Ј Archives of Yugoslavia, Belgrade networking Ј Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin Ј Bauhaus-Universitat Weimar, Archiv der Moderne ideas Ј Croatian Architects Association Archive, Graphic design Zagreb Aleksandra Mudrovčić and practice Ј Croatian Museum of Architecture of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Zagreb Ј Dragan Živadinov’s personal archive, Ljubljana Printing Ј Graz University of Technology Archives Print Grupa, Zagreb Ј Gustav Bohutinsky’s personal archive, Faculty of Architecture, Zagreb Ј Ivan Picelj’s Archives and Library, Contributors Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb Aida Abadžić Hodžić, Éva Bajkay, Ј Jernej Kraigher’s personal archive, Print run Dubravko Bačić, Ruth Betlheim, Ljubljana 300 Regina Bittner, Iva Ceraj, Ј Katarina Bebler’s personal archive, Publisher Zrinka Ivković,Tvrtko Jakovina, Ljubljana Muzej suvremene umjetnosti Zagreb Jasna Jakšić, Nataša Jakšić, Ј Klassik Stiftung Weimar © 2015 Muzej suvremene umjetnosti / Avenija Dubrovnik 17, Andrea Klobučar, Peter Krečič, Ј Marie-Luise Betlheim Collection, Zagreb Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb 10010 Zagreb, Hrvatska Lovorka Magaš Bilandžić, Vesna Ј Marija Vovk’s personal archive, Ljubljana ISBN: 978-953-7615-84-0 tel. +385 1 60 52 700 Meštrić, Antonija Mlikota, Maroje Ј Modern Gallery Ljubljanja fax. +385 1 60 52 798 Mrduljaš, Ana Ofak, Peter Peer, Ј Monica Stadler’s personal archive A CIP catalogue record for this book e-mail: [email protected] Bojana Pejić, Michael Siebenbrodt, Ј Museum of Architecture and Design, is available from the National and www.msu.hr Barbara Sterle Vurnik, Karin Šerman, Ljubljana University Library in Zagreb under no. -

Menadžment Plan Istorijskog Jezgra Cetinja

MENADŽMENT PLAN ISTORIJSKOG JEZGRA CETINJA VLADA CRNE GORE MINISTARSTVO KULTURE, SPORTA I MEDIJA MENADŽMENT PLAN ISTORIJSKOG JEZGRA CETINJA PODGORICA MAJ, 2009. GODINA Izvodi iz Ugovornih obaveza Ovaj Plan je urađen uz finansijsku pomoć UNESCO kancelarije u Veneciji - Regionalna kancelarija za nauku i kulturu u Evropi (UNESCO – BRESCE) i Ministarstva spoljnih poslova Italije – Cooperazione Italiana Upotrebljeni nazivi i prezentacija materijala u ovom tekstu ne podrazumijevaju ni na koji način izražavanje mišljenja Sekretarijata UNESCO u pogledu pravnog statusa bilo koje zemlje ili teritorije, grada ili područja ni njihovih nadležnosti, niti određivanja granica. Autor(i) su odgovorni za izbor i prezentaciju činjenica sadržanih u tekstu i u njemu izraženih mišljenja, koja ne odražavaju nužno i stavove UNESCO niti su za njega obavezujući. VLADA CRNE GORE MINISTARSTVO KULTURE, SPORTA I MEDIJA MENADŽMENT PLAN ISTORIJSKOG JEZGRA CETINJA PODGORICA MAJ, 2009. GODINA 1. SAžETAK 2. UVOD 2.1. Status Istorijskog jezgra Cetinja 2.2. Granice Istorijskog jezgra Cetinja 2.3. Granice zaštićene okoline (bafer zona) Istorijskog jezgra Cetinja 2.4. Značaj Istorijskog jezgra Cetinja 2.5. Integritet i autentičnost Istorijskog jezgra Cetinja 2.6. Stranci na Cetinju i o Cetinju 3. MENADžMENT PLAN ISTORIJSKOG JEZGRA CETINJA 3.1. Cilj Menadžment plana 3.2. Potreba za izradom Menadžment plana 3.3. Status Plana 3.4. Osnov za izradu i donošenje Plana 3.5. Proces izrade Menadžment plana 4. ISTORIJSKI RAZVOJ I NAčIN žIVOTA ISTORIJSKOG JEZGRA CETINJA 4.1. Istorijski razvoj 41.1. Nastanak Cetinja 4.1.2. Vrijeme Crnojevića 4-1.3. Cetinje u doba Mitropolita 4.1.4 Period dinastije Petrovića 4.1.5. Cetinje u Kraljevini Srba Hrvata i Slovenaca / Jugoslavija 4.1.6. -

“… New Content Will Require an Appropriate Form …” the Slovene Painter and Graphic Artist France Mihelič (1907 – 1998)

“… new content will require an appropriate form …” The Slovene Painter and Graphic Artist France Mihelič (1907 – 1998) “…um novo conteúdo requer uma forma apropriada...” O pintor e o artista gráfico esloveno France Mihelič (1907 – 1998) Dra. Marjeta Ciglenečki Como citar: CIGLENEČKI, M. “… new content will require an appropriate form …” The Slovene Painter and Graphic Artist France Mihelič (1907 – 1998). MODOS. Revista de História da Arte. Campinas, v. 1, n.3, p.26-46, set. 2017. Disponível em: ˂http://www.publionline.iar. unicamp.br/index.php/mod/article/view/864˃; DOI: https://doi.org/10.24978/mod.v1i3.864 Imagem: Midsummer Night, wood-cut in colour, 1954. (Pokrajinski muzej Ptuj-Ormož, photo Boris Farič). Detalhe. “… new content will require an appropriate form …” The Slovene Painter and Graphic Artist France Mihelič (1907 – 1998) “…um novo conteúdo requer uma forma apropriada...” O pintor e o artista gráfico esloveno France Mihelič (1907 – 1998) Dra. Marjeta Ciglenečki* Abstract The paper deals with the question of modernism in the post WW II period when the new political situation in Eastern Europe brought significant changes in art. The case of the Slovene painter France Mihelič (1907– 1998) illustrates how important personal experience was in the transformation from realism to modernism as well as how crucial it was for a talented artist to be acquainted with contemporary trends in the main Western European art centres. After WW II, most Slovene artists travelled to Paris in order to advance creatively, yet France Mihelič’s stay in the French city (1950) stands out. Mihelič is an acknowledged representative of fantastic art who reached his artistic peak in the 1950s when he exhibited and received awards at key art events in Europe and South America. -

Non-Aligned Modernity / Modernità Non Allineata

Milan, 16 September 2016 , FM Centro per l'Arte Contemporanea, the new center for contemporary art and collecting inaugurated last April at the Frigoriferi Milanesi, reopens its exhibition season on 26 October with three new exhibitions and a cycle of meetings aimed at art collectors. NON-ALIGNED MODERNITY / MODERNITÀ NON ALLINEATA Eastern-European Art and Archives from the Marinko Sudac Collection / Arte e Archivi dell’Est Europa dalla Collezione Marinko Sudac 27 October – 23 December 2016 Curated by Marco Scotini, in collaboration with Andris Brinkmanis and Lorenzo Paini 25 October 2016, 11 am - press preview 26 October 2016, 6 pm - opening event 27 October 2016, 7 pm - exhibition talk Under the patronage of: Republic of Croatia, Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs Consolato Generale della Repubblica di Croazia, Milano Ente Nazionale Croato per il Turismo, Milano After L’Inarchiviabile/The Unarchivable , an extensive review of the Italian art in the 1970s, FM Centro per l’Arte Contemporanea’s exhibition program continues with a second event, once again concerning an artistic scene that is less known and yet to be discovered. Despite the international prestige of some of its representatives, this is an almost submerged reality but one that represents an exceptional contribution to the history of art in the second half of the twentieth century. Non-Aligned Modernity not only tackles art in the nations of Eastern Europe but attempts to investigate an anomalous and anything but marginal chapter in their history, which cannot be framed within the ideology of the Soviet Bloc nor within the liberalistic model of Western democracies. -

Zivot Umjetnosti, 7-8, 1968, Izdavac

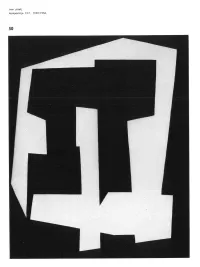

ivan picelj kompozicija 15/1, 1952./1956. 50 vlado kristl varijanta, 1958./1962. 51 igor zidić apstrahiranje predmetnosti i oblici apstrakcije u hrvatskom slikarstvu 1951/1968. bilješke aleksandar srnec kompozicija, 1956. 52 Opće je mjesto kritičke svijesti da pojam apstraktne umjetnosti ne znači više ono što je značio prije pola stoljeća, pa ni ono što je značio još prije dvadeset godina. Da je razvoj ove umjetnosti tada prestao, da se ona uslijed iscrpljenja urušila u se svejedno bi smo bili u prilici da zapazimo oscilacije značenja pojma. Domašaj svijesti u naporu da razumije i od redi pojavu ne može izbjeći ograničenjima same svi jesti. Zato se pred različitim očima svaka pojava raspada u toliko različitih pojavnosti koliko je razli čitih promatrača; ni jedan vid ne govori o gleda nome toliko koliko o viđenome — što će reći, da se, u svemu što gleda, oko i samo ogleda: vid je, tako đer, dio viđenoga. Ne treba, stoga, pomišljati da je 1918. ili 1948. po stojala apsolutna suglasnost o značenju pojma ap straktne umjetnosti ili pak, da će ikad i postojati. Ali činjenica da apstraktna umjetnost nije do sada »potrošila« oblike svog postojanja kaže nam da se pojam o njoj mora izmijeniti već i zbog toga što se ona mijenjala. Slikovito će nam otvoriti put razumijevanju naravi njezina početka jedan nedovoljno iskorišten aspekt predobro poznate priče o izvrnutoj slici u ateljeu Kandinskoga. Zatomimo li znatiželju povjesnika, koji u datumu događaja (1908.) vidi razlog pričanja, obratit ćemo pozornost okolnostima u kojima je vi đena pseudoprva pseudoapstraktna slika, u kojima je ta i takva slika — ni prva među apstraktnim, ni apstraktna među figurativnim — bila, dakle, pse- udoviđena. -

Enformel - Slikarstvo I Kiparstvo U Hrvatskoj Poslijeratnoj Umjetnosti

Enformel - slikarstvo i kiparstvo u hrvatskoj poslijeratnoj umjetnosti Babac, Ana-Emanuela Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Rijeci, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:186:920143 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-30 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of the University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences - FHSSRI Repository Sveuĉilište u Rijeci Filozofski fakultet u Rijeci Odsjek za povijest umjetnosti Studentica: Ana-Emanuela Babac ENFORMEL – SLIKARSTVO I KIPARSTVO U HRVATSKOJ POSLIJERATNOJ UMJETNOSTI Završni rad Mentorica: dr. sc. Julija Lozzi Barković red. prof. Rijeka, rujan 2020. SADRŢAJ 1. UVOD .................................................................................................................................... 1 2. POVIJESNI KONTEKST I UTJECAJ POLITIKE NA RAZVOJ UMJETNOSTI .............. 2 2.1. Neposredno poraće .......................................................................................................... 2 2.2. Pomaci poĉetkom pedesetih ............................................................................................ 4 2.3. Ograniĉena liberalizacija šezdesetih ................................................................................ 6 3. POJAVA I KARAKTERISTIKE ENFORMELA ................................................................ -

Šime Perić U Dijecezanskom Muzeju Požeške Biskupije

ŠIME PERIĆ U DIJECEZANSKOM MUZEJU POŽEŠKE BISKUPIJE ŠIME PERIĆ U DIJECEZANSKOM MUZEJU POŽEŠKE BISKUPIJE ŠIME PERIĆ U DIJECEZANSKOM MUZEJU POŽEŠKE BISKUPIJE Slike, skulpture i crteži BIBLIOTHECA ARS SACRA POSEGANA ŠIME PERIĆ U DIJECEZANSKOM MUZEJU POŽEŠKE BISKUPIJE – Slike, skulpture i crteži Nakladnik POŽEŠKA BISKUPIJA Za nakladnika IVICA ŽULJEVIĆ Urednici BISERKA RAUTER PLANČIĆ IVICA ŽULJEVIĆ Lektura MARIO BOŠNJAK Prijevod na engleski DAMIR LATIN Fotografije GORAN VRANIĆ DOKUMENTARNE FOTOGRAFIJE IZ SLIKAROVE OSTAVŠTINE Grafičko oblikovanje i priprema TOMISLAV KOŠĆAK Tisak DENONA d.o.o., Zagreb Požega, kolovoz 2020. CIP zapis je dostupan u računalnome katalogu Nacionalne i sveučilišne knjižnice u Zagrebu pod brojem 001070730. ISBN 978-953-7647-35-3 ŠIME PERIĆ U DIJECEZANSKOM MUZEJU POŽEŠKE BISKUPIJE Slike, skulpture i crteži POŽEGA, 2020. Slika je život sâm. Šime Perić u razgovoru s Marijom Grgičević za Večernji list, 4. V. 1960. (foto Branimir Baković) KAZALO Antun Škvorčević Proslov 7 Biserka Rauter Plančić Šime Perić – život i djelo 11 Reprodukcije 25 Summary 99 Katalog 103 Samostalne i skupne izložbe 115 Nagrade i odlikovanja 129 Literatura 131 6 PROSLOV ANTUN ŠKVORČEVIĆ požeški biskup UMJETNIK ŠIME PERIĆ sa suprugom Tonkom Perić Kaliterna darovao je Požeškoj biskupiji osamdesetak svojih djela te ona u Dijecezanskom muzeju u Požegi svjedoče o njegovu doprinosu hrvatskom duhovnom identitetu dvadesetog stoljeća. Želja nam je da tiska- njem knjige Šime Perić u Dijecezanskom muzeju Požeške biskupije – Slike, skulpture i crteži te izložbom o stotoj obljetnici umjetnikova rođenja (10. ožujka 2020.) i prvoj godiš- njici smrti (14. kolovoza 2020.) upoznamo našu javnost sa spomenutim djelima, te i na taj način izrazimo duboku zahvalnost donatorima za povjerenje i velikodušnost koju su nam iskazali. -

Vladimir-Peter-Goss-The-Beginnings

Vladimir Peter Goss THE BEGINNINGS OF CROATIAN ART Published by Ibis grafika d.o.o. IV. Ravnice 25 Zagreb, Croatia Editor Krešimir Krnic This electronic edition is published in October 2020. This is PDF rendering of epub edition of the same book. ISBN 978-953-7997-97-7 VLADIMIR PETER GOSS THE BEGINNINGS OF CROATIAN ART Zagreb 2020 Contents Author’s Preface ........................................................................................V What is “Croatia”? Space, spirit, nature, culture ....................................1 Rome in Illyricum – the first historical “Pre-Croatian” landscape ...11 Creativity in Croatian Space ..................................................................35 Branimir’s Croatia ...................................................................................75 Zvonimir’s Croatia .................................................................................137 Interlude of the 12th c. and the Croatia of Herceg Koloman ............165 Et in Arcadia Ego ...................................................................................231 The catastrophe of Turkish conquest ..................................................263 Croatia Rediviva ....................................................................................269 Forest City ..............................................................................................277 Literature ................................................................................................303 List of Illustrations ................................................................................324 -

IV Salon Petar Lubarda Crnogorska Galerija Umjetnosti “Miodrag Dado Đurić“ Decembar 2018

IV Salon Petar Lubarda Crnogorska galerija umjetnosti “Miodrag Dado Đurić“ Decembar 2018. Cetinje 1 IV Salon Petar Lubarda Crna Gora Ministarstvo kulture, Narodni Muzej Crne Gore Crnogorska galerija umjetnosti „Miodrag Dado Đurić“ decembar 2018. Cetinje Izdavač: Ministarstvo kulture Crne Gore IV Salon Za izdavača: Aleksandar Bogdanović, ministar kulture Urednica: Petar Dragica Milić, generalna direktorka Direktorata za kulturno-umjetničko stvaralaštvo Selektorka: Petrica Duletić,istoričarka umjetnosti Lubarda Žiri za dodjelu Nagrade „Petar Lubarda“: Crnogorska galerija umjetnosti “Miodrag Dado Đurić“ Predsjednik žirija: Decembar 2018. Cetinje Aleksandar Čilikov, istoričar umjetnosti Članovi žirija: Filip Janković , istaknuti kulturni stvaralac,likovni umjetnik; Svetlana Racanović,istoričarka umjetnosti; Jelena Tomašević,slikarka; Aldemar Ibrahimović,slikar Lektura: Marijana Brajović Fotografije: Duško Miljanić Lazar Pejović Anka Gardašević Dizajn: DPC Podgorica Štampa: DPC Podgorica CrnaCrna Gora Gora Tiraž: 1000kom MinistarstvoMinistarstvo kulture kulture Cetinje, 2018. Salon Petar Lubarda, prema tradiciji, Crna Gora i njena priroda, važan su ambijent predstavlja javnosti na uvid tekuću za umjetnike koji tu žive, ali i za one koji je produkciju (ne stariju od tri godine ) nose u svojoj memoriji.Ona je inspiracija ostvarenu u svim likovnim disciplinama. stvaraocima, koji iz nje crpe imaginaciju, Presjekom izloženih odabranih kreativnu energiju i nalaze svoju poruku. radova,potvrđuje se kako je riječ o Crna Gora je svojom istorijom i svojom podsticajnoj izložbi u njenim daljnjim prirodom gotovo predodređena za liturgiju promišljanjima i realizacijama, time umjetničke kulture. osnažujući njen značaj. Petar Lubarda je govorio : „Svi ovi silni utisci Stvaralačkim autorskim angažmanom koje sam upijao požudnošću, instinktom i umjetničkom produkcijom Salon sirove i naivne prirode, gomilali su se u meni omogućuje likovnim umjetnicima referiranje i spleli u čudno klupko. -

DESIGN and INDUSTRY: the Role and Impact of Industrial Design in Post-War Yugoslavia

Special Call “Design Policies: Between Dictatorship and Resistance” | December 2015 Editorial DESIGN AND INDUSTRY: The Role and Impact of Industrial Design in Post-War Yugoslavia Dora Vanette, Parsons The New School for Design, New York Key Words Yugoslavia, midcentury, industrial design, media ABSTRACT This study offers an overview of the design developments in the period following the Second World War in Yugoslavia and indicate the points of contact and departure between an emerging generation of architects and designers and state sanctioned design. The goal of this paper is to trace the development of the discipline of industrial design in this context, and argue for its revolutionary position in the development of a modern Yugoslavia. INTRODUCTION Following the end of World War II a new generation of architects and designers emerged in Yugoslavia, seeking to mediate socialist ideology with modernist forms. The group, mostly gathered around the progressive environment of the newly established Academy of Applied Art (1949-1955), attempted to promote art and design that was highly functional and aesthetically pleasing, and most importantly, available to all. What began as a probing of design terminology became a wide-reaching attempt to 1/15 www.iade.pt/unidcom/radicaldesignist | ISSN 1646-5288 promote modernist design as the appropriate expression of contemporary life. Through forming design organizations and developing relationships with manufacturers, the designers strove to bring their products to the market, at the same time utilizing various design publications in an attempt to educate the public on what was believed to be proper design. Finally, these ideas were disseminated to an international public through participation and organization of design fairs. -

Conflicting Visions of Modernity and the Post-War Modern

Socialism and Modernity Ljiljana Kolešnik 107 • • LjiLjana KoLešniK Conflicting Visions of Modernity and the Post-war Modern art Socialism and Modernity Ljiljana Kolešnik Conflicting Visions of Modernity and the Post-war Modern art 109 In the political and cultural sense, the period between the end of World War II and the early of the post-war Yugoslav society. In the mid-fifties this heroic role of the collective - seventies was undoubtedly one of the most dynamic and complex episodes in the recent as it was defined in the early post- war period - started to change and at the end of world history. Thanks to the general enthusiasm of the post-war modernisation and the decade it was openly challenged by re-evaluated notion of (creative) individuality. endless faith in science and technology, it generated the modern urban (post)industrial Heroism was now bestowed on the individual artistic gesture and a there emerged a society of the second half of the 20th century. Given the degree and scope of wartime completely different type of abstract art that which proved to be much closer to the destruction, positive impacts of the modernisation process, which truly began only after system of values of the consumer society. Almost mythical projection of individualism as Marshall’s plan was adopted in 1947, were most evident on the European continent. its mainstay and gestural abstraction offered the concept of art as an autonomous field of Due to hard work, creativity and readiness of all classes to contribute to building of reality framing the artist’s everyday 'struggle' to finding means of expression and design a new society in the early post-war period, the strenuous phase of reconstruction in methods that give the possibility of releasing profoundly unconscious, archetypal layers most European countries was over in the mid-fifties.