Allen Kirkbride Townhead Farm, Askrigg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aysgarth Falls Hotel

THE UPPER WENSLEYDALE NEWSLETTER Issue 256 April 2019 Stacey Moore Donation please: 30p suggested or more if you wish Covering Upper Wensleydale from Wensley to Garsdale Head plus Walden and Bishopdale, Covering UpperSwaledale Wensleydale from from Keld Wensley to Gunnerside to Garsdale plus Cowgill Head, within Upper Walden Dentdale. and Bishopdale, Swaledale from Keld to Gunnerside plus Cowgill in Upper Dentdale. Guest Editorial punch in a post-code and we’re off. The OS maps of Great Britain were once regarded as In 1811 William Wordsworth wrote a poem one of the modern wonders of the world. Now I about being ‘surprised by joy’ and in 1955 the read that fewer and fewer are being produced as Christian writer C S Lewis published an account there is less and less ‘call’ for them. So, ‘Good- of his early life, taking the same phrase as his o’ I say wickedly, when the siren voice of the title. It is a lovely one and it lingers in the sat nav does a wobbly and someone ends up on memory. the edge of a drop. Something like this once When were you last ‘surprised by joy?’ happened to me and it did teach me, I hope, not When you read this, the chances are that to put all my trust in the princes of technology. Spring might have arrived, or at least, be on its I think what I’m minding these days is an way. I write this in early March on a day of increasing lack of spontaneity in modern life, intense cold and severe floods, caused by the erosion of the genuine ‘hands on’ torrential rains and melt-water from recent experience. -

Full Edition

THE UPPER WENSLEYDALE NEWSLETTER Issue 229 October 2016 Donation please: 30p suggested or more if you wish Covering Upper Wensleydale from Wensley to Garsdale Head, with Walden and Bishopdale, Swaledale from Keld to Gunnerside plus Cowgill in Upper Dentdale. Published by Upper Wensleydale The Upper Wensleydale Newsletter Newsletter Burnside Coach House, Burtersett Road, Hawes DL8 3NT Tel: 667785 Issue 229 October 2016 Email for submission of articles, what’s ons, letters etc.:[email protected] Features Competition 4 Newsletters on the Web, simply enter ____________________________ “Upper Wensleydale Newsletter” or Swaledale Mountain Rescue 12 ‘‘Welcome to Wensleydale’ Archive copies back to 1995 are in the Dales ________________ ____________ Countryside Museum resources room. Wensleydale Wheels 7 ____________________________ Committee: Alan S.Watkinson, A684 9 and 10 Malcolm Carruthers, ____________________________ Barry Cruickshanks (Web), Police Report 18 Sue E .Duffield, Karen Jones, ____________________________ Alastair Macintosh, Neil Piper, Karen Prudden Doctor’s Rotas 17 Janet W. Thomson (Treasurer), ____________________________ Peter Wood Message from Spain 16 Final processing: ___________________________ Sarah Champion, Adrian Janke. Jane Ritchie 21 Postal distribution: Derek Stephens ____________________________ What’s On 13 ________________________ PLEASE NOTE Plus all the regulars This web-copy does not contain the commercial adverts which are in the full Newsletter. Whilst we try to ensure that all information is As a general rule we only accept adverts from correct we cannot be held legally responsible within the circulation area and no more than for omissions or inaccuracies in articles, one-third of each issue is taken up with them. adverts or listings, or for any inconvenience caused. Views expressed in articles are the - Advertising sole responsibility of the person by lined. -

The Old Goat House & the Piggery, Thornton Rust

Hawes 01969 667744 Bentham 01524 26 2044 Leyburn 01969 622936 Settle 01729 825311 www.jrhopper.com Market Place, Leyburn London 02074 098451 North Yorkshire DL8 5BD [email protected] “For Sales In The Dales” 01969 622936 The Old Goat House & The Piggery, Thornton Rust Character Barn Conversion & Open Plan Living Ample Parking. Patio Garden Detached Studio Holiday Let Accommodation With Stove, Additional Garden & 1.14 Village Location Kitchen & Dining Areas Acre Paddock Available By The Old Goat House : House & En Suite Bathrooms Separate Negotiation 2 Double Bedrooms The Piggery : One Bedroom Stunning Views Across The Studio With Wet Room Valley Offers Around £300,000 RESIDENTIAL SALES • LETTINGS • COMMERCIAL • PROPERTY CONSULTANCY Valuations, Surveys, Planning, Commercial & Business Transfers, Acquisitions, Conveyancing, Mortgage & Investment Advice, Inheritance Planning, Property, Antique & Household Auctions, Removals J. R. Hopper & Co. is a trading name for J. R. Hopper & Co. (Property Services) Ltd. Registered: England No. 3438347. Registered Office: Hall House, Woodhall, DL8 3LB. Directors: L. B. Carlisle, E. J. Carlisle The Old Goat House & The Piggery, Thornton Rust DESCRIPTION The Old Goat House & Piggery are set in a quiet position enjoying fantastic views over the valley. Thornton Rust is a small village in the Yorkshire Dales National Park. It has a village hall and a chapel, and an active community life if desired. The village is 3 miles from both Askrigg & Bainbridge and just 2 miles from Aysgarth. In Aysgarth is a village shop, two pubs, cafes, Church and doctors surgery. The market towns of Hawes & Leyburn being 7 & 11 miles respectively. Sitting on the slopes of Addlebrough, it is surrounded by glorious hills and dales and is popular with walkers. -

For More Routes See

THE TOUR DE FRANCE TWO COLS ROUTE Start/Finish Reeth or Hawes National Park Centre Distance 40 miles (67km) Refreshments Askrigg, Carperby, Castle Bolton, Reeth, Gunnerside, Muker & Hardraw Toilets Reeth, Hawes, Castle Bolton Nearest train station Redmire on the Wensleydale Railway is just off the route A cracking road route taking in the iconic climbs of Grinton Moor and Buttertubs which featured so spectacularly in the 2014 Tour de France. In essence this route heads over Grinton Moor into Wensleydale, follows the valley westwards, then climbs Buttertubs and returns along Swaledale. Of course that means two long steep climbs and fast descents to cross the high moorland in between the valleys. 1. Pass down through Reeth and cross the river. Shortly after on the right is the Dales Bike Centre. The main road then goes sharp left by the Bridge Inn, but you turn right signed to Leyburn. 2. Climb steeply up, cross a cattle grid and continue on passing Grinton Youth Hostel. The road zig zags over a stream and continues to climb up on to the moorland passing a military area. At a crossroads go straight on and descend in to Leyburn. 3. Turn right as you enter town and go straight over at a mini-roundabout. Descend away from Leyburn on the A684, and then take the first road on the right after 1.5 miles signed Preston and Redmire. 4. Follow this road through to Redmire (short diversion to Bolton Castle) and continue on to Carperby. Another short diversion takes you to Aysgarth Falls. 5. Continue to follow this road up Wensleydale passing through Woodhall and Askrigg. -

THE LITTLE WHITE BUS Acorn Wensleydale Flyer

GARSDALE STATION SHUTTLE Acorn Wensleydale Flyer 856 THE LITTLE WHITE BUS linking Garsdale Station, Hardraw, Hawes & Gayle Gayle - Hawes - Leyburn - Bedale - Northallerton FROM HAWES MARKET PLACE, BOARD INN ENSLEYDALE OYAGER Sundays W V 156 Mondays & Fridays: 0932, 1547, 1657 & 1852 Tuesdays, Wednesdays & Thursdays: 0932 & 1852 Gayle Bus Shelter .. 1115 1435 1725 REVISED TIMES FROM 6th NOVEMBER 2017 Saturdays: 0952, 1547, 1657 & 1847 Hawes Market Place .. 1118 1438 1728 Sundays: 1007 & 1742 Bainbridge .. 1127 1447 1737 FROM GARSDALE STATION Aysgarth Falls Corner .. 1135 1455 1745 Gayle - Hawes - Askrigg - Mondays & Fridays: 1025, 1620, 1730 & 1945 West Witton .. 1142 1502 1752 Tuesdays, Wednesdays & Thursdays: 1025 & 1945 Wensley .. 1147 1507 1757 Aysgarth - Leyburn - Princes Gate Saturdays: 1040, 1620, 1730 & 1935 Leyburn Market Place arr. .. 1150 1510 1800 Sundays: 1045, 1815 (on request) & 1910 Leyburn Market Place dep. .. 1155 1515 1805 Constable Burton .. 1201 1521 1811 The Little White Bus Garsdale Station Shuttle Bus when not operating its scheduled services is available for booking as a Patrick Brompton .. 1206 1526 1816 Demand Responsive Service. Crakehall .. 1210 1530 1820 This operates 0900 to 2100 seven days a week Bedale Market Place 0905 1215 1535 1825 (out of hours by advance arrangement). Bookings can be made by ringing the booking office. Leeming Bar White Rose 0910 1220 1540 1830 Concessionary passes are not valid on these booked journeys. Ainderby Steeple Green 0916 1226 1546 1836 Northallerton Rail Station 0921 1231 1551 1841 Find Out More Northallerton Buck Inn 0925 1235 1555 1845 Hawes National Park Centre Northallerton Buck Inn 0930 1240 1600 1850 (01969) 666210 Northallerton opp. -

Burn Cottage, Askrigg

Hawes 01969 667744 Settle 07726 596616 Leyburn 01969 622936 Kirkby Stephen 07434 788654 www.jrhopper.com London 02074 098451 01969 622936 [email protected] “For Sales In The Dales” Burn Cottage, Askrigg Deceptively Spacious Country Style Dining Kitchen Rear Patio/ Yard Character Cottage 2 Bathrooms Ideal Holiday, Investment Popular Village Location Currently Running As A Or Retirement Home 3 Bedrooms Successful Holiday Let (Pre Video Viewing Available Large Sitting Room With Covid) Multifuel Stove Guide Price £275,000 - £300,000 RESIDENTIAL SALES • LETTINGS • COMMERCIAL • PROPERTY CONSULTANCY Valuations, Surveys, Planning, Commercial & Business Transfers, Acquisitions, Conveyancing, Mortgage & Investment Advice, Inheritance Planning, Property, Antique & Household Auctions, Removals J. R. Hopper & Co. is a trading name for J. R. Hopper & Co. (Property Services) Ltd. Registered: England No. 3438347. Registered Office: Hall House, Woodhall, DL8 3LB. Directors: L. B. Carlisle, E. J. Carlisle Burn Cottage, Askrigg DESCRIPTION Burn Cottage is a deceptively spacious character cottage set in the popular village of Askrigg, in Upper Wensleydale. Askrigg is a picturesque village with its ancient market cross, notable church and cobbled central "green". It has a primary school, good general store, cafe, delicatessen, gift shop as well as 3 good pubs, a number of B&Bs and an excellent community life. It is famous for its Herriot connections, being the village where the series All Creatures Great & Small was filmed. The cottage is tucked away in a quiet location, just off the main street. The property boasts charm with original character features, yet has been modernised sympathetically. It is in excellent order with modern bathrooms, fixtures and fittings. -

And Our Wonderful Holiday Cottages in the Yorkshire Dales

Welcome To Askrigg Cottage Holidays... …and our wonderful holiday cottages in the Yorkshire Dales We are a small family run self catering holiday cottage agency, with an emphasis on quality, comfort and service, and our holiday cottages are real homes from home. You can choose from traditional Yorkshire Dales houses and cottages, an old school and barn conversions, and all of our holiday homes are individual and historic, many of them listed buildings. All of the holiday cottages are quality inspected annually by Visit Britain so that you can rest assured that the star grading is an independent assessment and assurance of the quality of the holiday cottage. Our cottages are individually owned, with our owners looking after the properties themselves, and they really care about the small details that make your holiday special. We are happy to guide you to help you to tailor make your holiday and the most of the Yorkshire Dales. We know all of our cottages intimately, so if you have any requirements that are not mentioned in the descriptions, then please do not hesitate to contact us. We look forward to hearing from you. Accommodation Sleeps 2 Coal will be provided for the multifuel stove with the Minnie’s Cottage, Askrigg first bucket of coal provided in the rental. ****Gold Award There is a comfortable sitting/dining room with panoramic views, a beamed ceiling festooned with We ask that you pay us 50p per bucket of coal after This beautifully presented Grade 2 listed cottage nestles next to the horse brasses and the stunning inglenook fireplace. -

Appersett Near Hawes in Wensleydale, North

Lot 1 Lot 2 Lot 3 Lot 1 Lot 2 Lot 3 Appersett Near Hawes in Wensleydale, North Yorkshire Lot 1 : 1.4 Acres Approx of Riverside Land together with 384 Yards of Fishing Rights on Widdale Beck Lot 2 : Bog House – A Beautifully Secluded Traditional Stone Field Barn with 10.6 Acres and 340 Yards approx of Fishing Rights Lot 3 : High and Low Pastures – 41.6 Acres of Pasture Land 4 North End, Bedale, North Yorkshire DL8 1PA – 01677 425950 www.robinjessop.co.uk [email protected] Appersett Near Hawes in Wensleydale, North Yorkshire Lot 1 : Appersett Near Hawes in Wensleydale – 1.4 Acres Approx of Riverside Land together with 384 Yards of Fishing Rights on Widdale Beck – Guide Price £ Lot 2 : Bog House – A Beautifully Secluded Traditional Stone Field Barn with 10.6 Acres and 340 Yards approx of Fishing Rights on Widdale Beck – Guide Price £ Lot 3: High and Low Pastures – 41.6 Acres of Pasture Land – Guide Price £ SITUATION Lot 2 : Bog House – A Beautifully Secluded Traditional Stone Field The small village of Appersett is situated approximately 1 mile north west of Barn with 10.6 Acres and 340 Yards approx of Fishing Rights on the popular and thriving market town of Hawes in this very picturesque part Widdale Beck (edged green) of Upper Wensleydale in the Yorkshire Dales National Park. This lot comprises a traditional stone field barn known as Bog House. It is beautifully situated on the valley floor adjacent to the picturesque Widdale Lots 1 and 2 are situated adjacent to the minor road which leads south from Beck. -

Dales Bike Centre, Fremington DISTANCE: 63 Miles Over Two Days PICTURES: Alamy, a Chamings, M Jackson Handcycling the Dales | GREAT RIDES

WHERE: the Yorkshire Dales START/FINISH: Dales Bike Centre, Fremington DISTANCE: 63 miles over two days PICTURES: Alamy, A Chamings, M Jackson HANDCYCLING THE DALES | GREAT RIDES GREAT RIDES HANDCYCLING the DALes Handcyclist Alan Grace created a two-day tour in North Yorkshire to celebrate the 2014 Tour de France and the life of handcycling friend Gary Jackson he Grand Départ of the 2014 completed too many sportives to mention. Tour de France in Yorkshire was The common denominator among the T a spectacular success, but as cycles everyone brought was low gearing a handcyclist I felt there was something for the climbs! missing: a legacy for handcyclists. When the Tour came to London in 2007, there Côte de Buttertubs was an official race on the Mall that drew Our arrival on Friday night was greeted with handcyclists from all over the world. So this torrential rain. The few of our group who year, some friends and I decided to create braved camping in Reeth rather than B&Bs an event, the Dales 2-Day, to celebrate the were surprised when the owner of Orchard Tour and also to remember a handcycling Park Caravan and Camping offered them friend Gary Jackson, whom we’d said the use of a static caravan for the weekend farewell to in 2014. Gary was one of the for the same price, on the basis that it was first of us to ride the coast to coast. (Cycle’s much too wet to camp. We felt sorry for DO IT YOURSELF June-July 2007 issue carried an account.) several hundred Scouts camping in the field Arranging an event for handcyclists We would ride some of the Tour adjacent to the Dales Bike Centre. -

TDF-Map-And-Description.Pdf

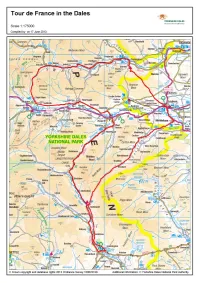

TdF in the Dales Start: Grassington National Park Centre car park Distance: 125km Ascent: 2500m Toilets: Grassington, Kettlewell, Buckden, Aysgarth Falls, Muker, Gunnerside, Reeth, Leyburn Cafes and shops: Grassington, Kettlewell, Buckden, Aysgarth Falls, Askrigg, Hawes, Muker, Gunnerside, Reeth, Leyburn This is a stunning route largely following the route of the Tour de France through the Yorkshire Dales National Park. Quiet roads, great scenery and four classic climbs. 1. Turn left out of the car park, down over the river and up to a T-junction. Turn right signed Kettlewell and follow this road all the way up Wharfedale passing through Kettlewell, Starbotton and Buckden. 2. Climb over Kidstones Pass then down a narrow twisty descent into Bishopdale. Easy run down the valley past the Street Head Inn and on to West Burton. After tight right- left bend, turn left signed ‘Aysgarth light vehicles only’. 3. At T-junction turn left, then shortly after turn right signed to Aysgarth Falls (the Tour is likely to stay on the main road but this alternative is on a quieter parallel road). Cross over the river with a view of the Upper Falls and up to a T-junction. 4. Turn left signed Hardraw and head up Wensleydale for 8 miles. Through Askrigg and keep on this road, ignoring the first turn-off to Hawes. Go past a second turn to Hawes (good place for refreshments if needed) and then turn right signed Muker via Buttertubs. 5. Up and over Buttertubs and fast descent to T-junction. Turn right down Swaledale and follow road down valley through Muker, Gunnerside, Low Row and Reeth. -

Askrigg Bottoms Meadow, Has Meadows)

Map: Explorer OL30, Yorkshire Dales Northern & Central areas. It is recommended that this leaflet is used in conjunction with the map. Nearest village: Askrigg (pubs, cafés, shops, toilets). Terrain: Easy. Level except one very short climb up a bank. Askrigg Bottoms Pavement, tracks, footpaths (muddy in places), squeeze stiles, gates, steps. Take care on the road, especially where the pavement gets narrow. Start and finish point: Askrigg car park (Grid ref: SD95029118). Meadow Alternatively, use the lay-by at Worton Bridge (Grid ref: SD95559029). Getting there without a car: National Cycle Network regional route 10. DalesBus 856 with a connecting demand-responsive bus service (see www.dalesbus.org/856.html). Nearest train station is about 11 miles to the west at Garsdale. The best time to visit a meadow is in June, as most of the wildflowers will be flowering by then. This is also a good time to visit the Dales as it’s just before the main tourist season starts. However, the walk is equally enjoyable in the autumn and at other times of the year. This is one of a series of walks incorporating Yorkshire Dales hay meadows. Other routes include Dentdale Meadows, Muker Meadow (Swaledale), Yockenthwaite Meadows (Langstrothdale) and Grassington Meadows (Wharfedale). All are available to download at www.ydmt.org/resources The leaflets have been produced as part of the Into the Meadows project, which aims to help people enjoy, understand and celebrate the Dales meadows. To find out more about the project and how YDMT has helped to restore meadows go to www.ydmt.org/haytime Into the Meadows has been funded by: A short, easy walk from Askrigg through a superb meadow and alongside the River Ure The European Agricultural Fund 1.7 miles / 2.8 km / 2 hours for Rural Development: Europe investing in rural areas This project is supported by the Rural Development Programme for England (RDPE) for which Defra is the Managing Authority, part funded by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development: Europe investing in rural areas. -

Download the Grassington Meadows Walk Guide

Map: Explorer OL2, Yorkshire Dales Southern & Western. It is recommended that this leaflet is used in conjunction with the map. Nearest village: Grassington (pubs, cafés, shops, heritage museum, toilets). Terrain: Easy. Mostly fairly level with two slight climbs. Tracks, footpaths Grassington (muddy in places), quiet lanes, ladder stiles, squeeze stiles, steps, gates. Start and finish point: National Park pay and display car park Grid ref: SE002637. Meadows Getting there without a car: Grassington is relatively well-served by buses (see www.prideofthedales.co.uk/72northand76.htm and www.getdown.org.uk/bus/bus/872.shtml) but the nearest train station - Gargrave - is about 9 miles to the south. There are cycle lockers and stands at the National Park Centre. The best time to visit a meadow is in June, as most of the wildflowers will be flowering by then. This is also a good time to visit the Dales as it’s just before the main tourist season starts. However, the walk is equally enjoyable in the autumn and at other times of the year. This is one of a series of walks incorporating Yorkshire Dales hay meadows. Other routes include Yockenthwaite Meadows (Langstrothdale), Askrigg Bottoms Meadow (Wensleydale), Dentdale Meadows and Muker Meadows (Swaledale). All are available to download at www.ydmt.org/resources The leaflets have been produced as part of the Into the Meadows project, which aims to help people enjoy, understand and celebrate the Dales meadows. To find out more about the project and how YDMT has helped to restore meadows go to www.ydmt.org/haytime