To Access Self-Archived Copy of the Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monuments in Toulouse

Welcome to N7 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL ADVICE > 3 STUDENT LIFE > 11 FOOD > 18 SPORT IN THE CITY> 27 VISITING MIDI-PYRÉNÉES AND FRANCE > 44 VISITING TOULOUSE > 36 INP-ENSEEIHT 2, rue Charles CAMICHEL B.P. 7122 31071 TOULOUSE Cedex 7 Tél. : +33 (0)534 322 000 http://www.enseeiht.fr Rédacteur en chef : Anne BRITTAIN Mise en page : Charline Suderie et Cédric Mirouze © Service Relations Entreprises & Communication Mars 2016 A poem By Thomas Longchamps, Jules Le Breton By Antoine Landry, Thomas Longchamps By Antoine Landry, Ayoub Namrani New, without friends … don’t be shy, Now let’s get serious for a moment, Foreign student, N7 is welcoming, Here comes the « integration », you will get You will have to work hard, whatever your It’s a new experience which never gonna be high, department, boring, With all the theme parties, above all the But if in class you pull your weight and pay You will discover a new school, WEI, attention, Where all the teachers and students are You will do funny things, you won’t know You won’t have to pass repeat session. cool. why. By Ayoub Namrani, Thomas Longchamps Located in the « Pink City », By Jules Le Breton, Ayoub Namrani By Antoine Landry, Jules Le Breton All days in there will drive you crazy, If you are in HYDRO, you will discover With many students and daily party, The school offers you different activities, water, Your journeys will be full of agony. You will dance, sing, do sports and go to Instead of GEA, where you will connect parties, wire, By Antoine Landry, Ayoub Namrani So many clubs which give you great oppor- While in EN, you are a GEA follower, tunities, Then in TR and INFO, you will be fed with Trust me you won’t regret, Then come aboard, it’s a chance to seize. -

Negotiations of Minority Ethnic Rugby League Players in the Cathar Country of France

Citation: Spracklen, K and Spracklen, C (2008) Negotiations of minority ethnic rugby league players in the Cathar country of France. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 43 (2). 201 - 218. ISSN 1012-6902 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690208095378 Link to Leeds Beckett Repository record: https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/359/ Document Version: Article (Accepted Version) The aim of the Leeds Beckett Repository is to provide open access to our research, as required by funder policies and permitted by publishers and copyright law. The Leeds Beckett repository holds a wide range of publications, each of which has been checked for copyright and the relevant embargo period has been applied by the Research Services team. We operate on a standard take-down policy. If you are the author or publisher of an output and you would like it removed from the repository, please contact us and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. Each thesis in the repository has been cleared where necessary by the author for third party copyright. If you would like a thesis to be removed from the repository or believe there is an issue with copyright, please contact us on [email protected] and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. DRAFT COPY – Version 2 (May 2008) Dr Karl Spracklen and Cliff Spracklen Carnegie Faculty of Sport and Education, Leeds Metropolitan University Contact details: Carnegie Faculty of Sport and Education, Leeds Metropolitan University Cavendish Hall, Headingley Campus, Leeds, United Kingdom, LS6 3QS [email protected] 0113 2832600 x 3608 7728 words Negotiations of Being and Becoming: minority ethnic rugby league players in the Cathar country of France Biographical details: Karl Spracklen is a Senior Lecturer in Socio-Cultural Aspects in Sport and Leisure at Leeds Metropolitan University, United Kingdom. -

180319 Presse-1718 J27.Pdf

28 - MIDI OLYMPIQUE LUNDI 19 MARS 2018 Pro D2 27e journée Résultats Le point SOYAUX-ANGOULÊME - BAYONNE 19 - 6 BÉZIERS - MONTAUBAN 12 - 12 BIARRITZ (BO) - AURILLAC 38 - 16 ★ CARCASSONNE (BO) - NARBONNE 52 - 17 GROS COUP DU FCG MASSY - PERPIGNAN 19 - 11 NEVERS - DAX 30 - 13 NARBONNE RELÉGUÉ Le XV VANNES (BO) - COLOMIERS 37 - 0 de la semaine ★ MONT-DE-MARSAN - GRENOBLE 13 - 19 la journée en allant s’imposer sur la Par David BOURNIQUEL pelouse de Mont-de-Marsan. Un succès Premier enseignement mathématique du qui propulse les Isérois à la quatrième e ★ Prochaine journée (28 ) 22 - 25 mars 2018 week-end, le festival à huit essais de place, qualificative pour un barrage à Dax - Béziers jeu. 22/03 21 heures Carcassonne face à Narbonne a condam- domicile, au nez et à la barbe de Biarritz 15 Porical Béziers qui, malgré sa victoire contre Aurillac se Aurillac - Vannes né le RCNM qui jouera la saison pro- ven. 23/03 20 heures retrouve barragiste à l’extérieur au soir de 14 Bly Vannes Colomiers - Biarritz ven. 23/03 20 heures chaine en Fédérale 1. Triste épilogue d’une saison noire pour les Tango, qui cette 27e journée. En concédant sa pre- 13 Dachary Biarritz Grenoble - Carcassonne mière défaite de la saison sur sa pelouse, ven. 23/03 20 heures n’ont jamais évolué au niveau d’exigence 12 Roger Soyaux-Angoulême Montauban - Massy ven. 23/03 20 heures requis par ce championnat. Qui accompa- Mont-de-Marsan fait du surplace et man- que une occasion de rester au contact de 11 Oltmann Carcassonne Narbonne - Nevers ven. -

Download the Trophy Cabinet

ACT Heritage Library Heritage ACT Captain of the Canberra Raiders Mal Meninga holding up the Winfield Cup to proud fans after the team won the club’s first premiership against Balmain, 1989. The Trophy CabINeT Guy Hansen Rugby league is a game that teaches you lessons. My big lesson Looking back to those days I realise that football was very much came in 1976 when the mighty Parramatta Eels were moving in part of the fabric of the Sydney in which I grew up. The possibility a seemingly unstoppable march towards premiership glory. As of grand final glory provided an opportunity for communities to a 12-year-old, the transformation of Parramatta from perennial take pride in the achievements of the local warriors who went cellar-dwellers was a formative event. I had paid my dues with into battle each weekend. Winning the premiership for the first fortnightly visits to Cumberland Oval and was confident that a time signalled the coming of age for a locality and caused scenes Parramatta premiership victory was just around the corner. In the of wild celebration. Parramatta’s victory over Newtown in 1981 week before the grand final I found myself sitting on a railway saw residents of Sydney’s western city spill onto the streets in bridge above Church Street, Parramatta, watching Ray Higgs, a spontaneous outpouring of joy. Children waved flags from the the legendary tackling machine and Parramatta captain, lead family car while Dad honked the horn. Some over-exuberant fans the first-grade team on a parade through the city. -

703 Prelims.P65

Football in France Global Sport Cultures Eds Gary Armstrong, Brunel University, Richard Giulianotti, University of Aberdeen, and David Andrews, The University of Maryland From the Olympics and the World Cup to extreme sports and kabaddi, the social significance of sport at both global and local levels has become increasingly clear in recent years. The contested nature of identity is widely addressed in the social sciences, but sport as a particularly revealing site of such contestation, in both industrialising and post-industrial nations, has been less fruitfully explored. Further, sport and sporting corporations are increasingly powerful players in the world economy. Sport is now central to the social and technological development of mass media, notably in telecommunications and digital television. It is also a crucial medium through which specific populations and political elites communicate and interact with each other on a global stage. Berg publishers are pleased to announce a new book series that will examine and evaluate the role of sport in the contemporary world. Truly global in scope, the series seeks to adopt a grounded, constructively critical stance towards prior work within sport studies and to answer such questions as: • How are sports experienced and practised at the everyday level within local settings? • How do specific cultures construct and negotiate forms of social stratification (such as gender, class, ethnicity) within sporting contexts? • What is the impact of mediation and corporate globalisation upon local sports cultures? Determinedly interdisciplinary, the series will nevertheless privilege anthropological, historical and sociological approaches, but will consider submissions from cultural studies, economics, geography, human kinetics, international relations, law, philosophy and political science. -

Saison 2014/2015 : N°28 Du 28/04/2015

Saison 2014/2015 : n°28 du 28/04/2015 Saison 2014/2015 : n°28 du 28/04/2015 Saison 2014/2015 : n°28 du 28/04/2015 MASSY : les espoirs de maintien s’éloignent ! (vidéos) http://vibrez-rugby-d2.com - By patrick - Updated: 26 avril 2015 Défait à Carcassonne 20/17, Massy a quasiment, à deux matches de la fin de la saison, les deux pieds en Fédérale1. Dans un match où les maladresses ont été légion et qui a eu du mal à trouver son rythme, les massicois menés 17/0 jusqu’à la 55e. minute ont réussi à refaire leur retard en un petit quart d’heure (17/17 à la 70e.) pour finalement mourir à 3 points de l’USC 17/20. Deux pénaltouches mal négociées en fin de rencontre auraient pu permettre aux coéquipiers de Bakary MEITE de repartir avec les 4 points de la victoire. Retrouvez les réactions en vidéo d’Adrien LATORRE et de Bakary MEITE. https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=hi8yrfyONfI https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=KXRO-4AqJpI Massy passe tout près de l’exploit ! http://essonneinfo.fr - ESSONNE INFO | Par Jérôme Lemonnier | Publié le lundi 27 avril 2015 à 05:45 Menés 17-0, les Massicois ont failli faire basculer le match face à Carcassonne. Seulement, ces derniers ont encaissé une pénalité dans les derniers instants, les privant des points du match nul. Dans sa lutte pour se maintenir en Pro D2, le RCME garde un mince espoir, mais il n’est plus maître de son destin. -

Finale Coupe De France Lord Derby

Finale Coupe de France Lord Derby La revue de presse Retrouvez la couverture média de la victoire historique du Toulouse Olympique XIII en finale de Coupe de France. Toulouse Olympique XIII - 107, avenue Frédéric Estèbe - 31200 Toulouse M° ligne B : Barrière de Paris - (33)5 61 57 80 00 - www.to13.com 3 avril 2014 – La Dépêche du Midi Toulouse Olympique XIII - 107, avenue Frédéric Estèbe - 31200 Toulouse M° ligne B : Barrière de Paris - (33)5 61 57 80 00 - www.to13.com 7 avril 2014 – Le Midi Olympique Toulouse Olympique XIII - 107, avenue Frédéric Estèbe - 31200 Toulouse M° ligne B : Barrière de Paris - (33)5 61 57 80 00 - www.to13.com 8 avril 2014 – La Dépêche du Midi Toulouse Olympique XIII - 107, avenue Frédéric Estèbe - 31200 Toulouse M° ligne B : Barrière de Paris - (33)5 61 57 80 00 - www.to13.com 9 avril 2014 – La Dépêche du Midi Toulouse Olympique XIII - 107, avenue Frédéric Estèbe - 31200 Toulouse M° ligne B : Barrière de Paris - (33)5 61 57 80 00 - www.to13.com 10 avril 2014 – La Dépêche du Midi Toulouse Olympique XIII - 107, avenue Frédéric Estèbe - 31200 Toulouse M° ligne B : Barrière de Paris - (33)5 61 57 80 00 - www.to13.com 10 avril 2014 – La Dépêche du Midi Toulouse Olympique XIII - 107, avenue Frédéric Estèbe - 31200 Toulouse M° ligne B : Barrière de Paris - (33)5 61 57 80 00 - www.to13.com 11 avril 2014 – ladepeche.fr Toulouse Olympique XIII - 107, avenue Frédéric Estèbe - 31200 Toulouse M° ligne B : Barrière de Paris - (33)5 61 57 80 00 - www.to13.com 11 avril 2014 – La Dépêche du Midi Toulouse Olympique XIII - 107, avenue Frédéric Estèbe - 31200 Toulouse M° ligne B : Barrière de Paris - (33)5 61 57 80 00 - www.to13.com 11 avril 2014 – sportchoc.tv Coupe : Carcassonne mène 2 à 0 Rares ont été les finales de Coupe entre Carcassonne et Toulouse. -

180409 Presse-1718 J29.Pdf

14 - MIDI OLYMPIQUE LUNDI 9 AVRIL 2018 Pro D2 29e journée Résultats Le point MONT-DE-MARSAN - PERPIGNAN (BD) 23 - 18 BAYONNE - COLOMIERS (BD) 23 - 22 BÉZIERS 19 - 38 ★ CARCASSONNE - GRENOBLE (BO) - AURILLAC 46 - 23 MASSY - BIARRITZ 31 - 24 LES JEUX Le XV NEVERS - SOYAUX-ANGOULÊME 34 - 19 ★ VANNES (BO) - NARBONNE 50 - 28 SONT FAITS, OU PRESQUE de la semaine MONTAUBAN - DAX 30 - 20 Par Jean-Luc GONZALEZ extra-sportifs, semble moins solide qu’une équipe biterroise restant sur sept matchs e ★ Prochaine journée (30 ) sans défaite. Jouer un match éliminatoire à 13 avril 2018 Dimanche, aux alentours de 16 h 20-25, on Aimé-Giral n’est pas non plus une Aurillac - Mont-de-Marsan dim. 15/04 14 h 30 connaîtra la grille de la phase éliminatoire 15 Salles Montauban « joyeuse » perspective. Il est bon de rappe- Béziers - Nevers dont le premier tour, celui des barrages, aura dim. 15/04 14 h 30 ler à l’équipe qui se rendra à Perpignan le 14 Bituniyata Massy lieu les 21 et 22 avril. Avant la dernière jour- Biarritz - Montauban dim. 15/04 14 h 30 week-end du 28-29 avril que Mont-de- née de la phase retour dont les matchs débu- 13 Hickes Vannes Colomiers - Massy Marsan et Béziers y ont déjà gagné cette sai- dim. 15/04 14 h 30 teront à 14 h 30, il est déjà acquis : que son. 12 Delage Massy Dax - Vannes dim. 15/04 14 h 30 Perpignan et Montauban sont déjà qualifiés Osons un scénario avant la dernière journée 11 Dupont pour les demi-finales ; que Grenoble, Mont- Grenoble Narbonne - Bayonne dim. -

Utilisation Du Modèle

JEROME CAZALBOU CARRIÈRE SPORTIVE (JOUEUR) CLUBS . Jusqu'en 1987 : Labastide-Beauvoir . 1987-2002 : Stade Toulousain SÉLECTIONS . 4 sélections en Equipe de France PALMARÈS . 7 titres de Champion de France . 1 titre de Champion d’Europe CARRIÈRE PROFESSIONNELLE . 34 matchs en Coupe d'Europe 48 ans . Vainqueur de la Coupe Latine en 1997 . Depuis 1989 : Carrière à la Société Générale. Actuellement Responsable régional des partenariats Ancien demi de sportifs et des relations avec les sportifs de haut niveau mêlée sur la délégation de Bordeaux. CARRIÈRE SPORTIVE international (MANAGER) . Depuis 2000 : Consultant pour France Télévisions CLUBS . 2003 – 2010 : Manager du club de l'Entente de la Vallée du Girou (Haute-Garonne) – Honneur Fédérale 1 19/03/2018 P.1 TITRE DE LA PRÉSENTATION C1 00/00/2017 1 SYLVAIN MARCONNET CARRIÈRE SPORTIVE (JOUEUR) CLUBS . Jusqu’en 1994 : Givors .1995-1997 : FC Grenoble . 1997-2010 : Stade Français Paris . 2010-2012 : Biarritz Olympique SÉLECTIONS : . XV de France 84 sélections CARRIÈRE PROFESSIONNELLE PALMARES 41 ans . 1999 : Vainqueur de la Coupe de France . Directeur Associé du groupe SportLab . Finaliste de la Coupe du Monde de Rugby en 1999 Ancien pilier et demi- finaliste en 2003 . Vainqueur du Tournoi des 6 Nations en 2002, 2004, AUTRES 2006,2007 . 2012 : Vainqueur du Challenge Européen . Participation au tournage de la série Société Générale « Terrain Favorable » TITRE DE LA PRÉSENTATION C1 00/00/2017 2 ROMAIN MAGELLAN CARRIÈRE SPORTIVE (JOUEUR) CLUBS CARRIÈRE PROFESSIONNELLE . 1992-1998 : FC Grenoble . Consultant pour Canal+, Eventeam . 1998-2001 : CS Bourgoin-Jallieu . 2001-2002 : Saracens SÉLECTIONS : . France U21 PALMARES 44 ans . 1992 : Vainqueur du Championnat de France Reichel . -

1Toulouse.Pdf

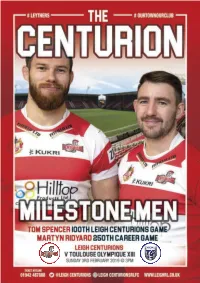

aaa Leigh v Toulouse 56pp.qxp_Layout 1 01/02/2019 08:49 Page 1 aaa Leigh v Toulouse 56pp.qxp_Layout 1 01/02/2019 08:39 Page 2 # LEYTHERS # OURTOWNOURCLUB# OURTOWNOURCLUB aaa Leigh v Toulouse 56pp.qxp_Layout 1 01/02/2019 08:39 Page 3 # LEYTHERS # OURTOWNOURCLUB# OURTOWNOURCLUB MIKEFROM LATHAM THE TOP CHAIRMAN,Welcome to Leigh Sports Village OPERATIONAL for that day would soon be our BOARD Messiah. Chris Hall came along and filmed the this afternoon’s Betfred On 1 November we had to file our new-look Leigh, working to put the Championship opener against preliminary 2019 squad list to the RFL. pride back into the club. His fantastic Toulouse Olympique. On it were just two names. By three-minute feature on ITV Granada It’s great to be back isn’t it? Last Christmas we had 20 and the reached out to 750k viewers. Sunday’s Warm Up game against metamorphosis was almost complete. The last few weeks have been hectic, London Broncos was a really The key to it all, appointing John Duffy preparing for the season and at the worthwhile exercise and it was great to as coach. He immediately injected Championship launch at York there was see over 2,000 Leigh fans in the positivity, local knowledge and a ready a palpable air of excitement for the ground, despite the bitterly cold smile, a bulging contacts book and with prospects of a great competition to weather. it a long list of players who were come. We are extremely grateful to our bursting to play for the club. -

Romain Manchia L’Avenir Du RCNM Merci À Vous, Supporters Romain Manchia Joue Au Poste De Deuxième Ligne

L’EDITO DE LA SEMAINE RÉACTION D’APRÈS MATCH par les coachs (Christian Labit head coach, avec Sébastien Buada et ÉTIENNE HERJEAN Steeve Kefu et Sébastien Petit pour la mêlée). Cette organisation terrain et Le score est lourd, mais contre une opérationnelle sera supportée par un équipe bien organisée comme Aurillac, Manager Général (Michel Macurdy) on paie cash nos erreurs. Il y a trop à côté du Président dont la principale de déchets. On a quand même des priorité cette saison sera le projet occasions franches d’essai, mais on ne sportif, et en particulier de recruter 2 fait pas le bon choix. Il y a beaucoup jockers médicaux immédiatement. de frustration. Mais il ne faut pas baisser Une deuxième augmentation de les bras, il reste encore 25 matchs. Il capital est en cours, et un nouveau faut continuer à travailler. Directeur Commercial et Marketing va rejoindre le club en Octobre. Je e BERNARD ARCHILLA m’étais engagé depuis le début à vouS ÊTES LE XV HOMME cultiver la transparence, et mettre La période trop longue d’instruction toutes mes forces pour remettre le juridique des divers contrats, et la racing dans une direction positive ; PRIX DES ABONNEMENTS POUR clarification des éléments financiers aujourd’hui je tiens à remercier toutes LA SAISON 2016/17 de la saison passée est maintenant les personnes qui croient en le RCNM, (NOUVEL ABONNÉ) : achevée. Aujourd’hui toute notre qui chacune en mettant sa pierre attention se porte sur 2 priorités contribue à construire un racine plus INTER. P. DE LACLAUSE : 285,00 € majeures : rattraper notre retard fort, plus combatif, plus soudé. -

Gorge De Galamus the Spooky Devils's Tarn What's on Around The

P-O Life /LIHLQWKH3\UÂQÂHV2ULHQWDOHV Walk the region TThehe SSpookypooky DDevils’sevils’s TTarnarn Out for the Day GGorgeorge DDee ggalAmusalAmus Festivals and Traditions WWhat’shat’s oonn aaroundround tthehe rregionegion AMÉLIOREZ VOTRE ANGLAIS Summer 2011 AND TEST YOUR FRENCH FREE / GRATUIT Nº 32 Your English Speaking Services Directory www.anglophone-direct.comw anglophone di ect co WINDOWS, DOORS, SHUTTERS & CONSERVATORIES IInstallingnstalling thethe vveryery bestbest windows,windows, ddoorsoors & shuttersshutters ssinceince 11980980 Call today or visit our showroom and ask to speak with one of our English speaking experts. We also design & install TRYBA beautiful conservatories. Check out our web site or see our advert on anglophone-direct.com for up to date details of all our special off ers and promotions SOCIETE www.tryba.com 2 Next to the restaurant “Le Clos des Lys” Edito... Register for our Bon dia! free weekly newsletter, and stay up to date with Summer’s here and it’s time to batten life in the Pyrénées-Orientales. down the hatches in the evening against www.anglophone -direct.com moustiques, moucherons and mouches if Installing the you don’t want to fi nd live raisins in your muesli in thee morning!morniinng! And of course, the festival season has arrived; Fete de la very best windows, musique, Feux de la Saint Jean, Havaneres , Sardanes…… Read all about these festivals, ferias and feasts of dance, fi re and doors & shutters music on pages 10 to 15 – any excuse for a bit of a bop! Evenings are already warm as I write this, and nights are not quite hot and sticky yet but showing their potential for a few sleepless since 1980 nights to come.