Always, Always, Others. Non-Classical Forays Into Modernism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dan Nadel, Hairy Who? 1966-1969, Artforum, February 2019, P. 164-167 REVIEWS

ARTFORUM H A L E s GLADYS NILSSON Dan Nadel, Hairy Who? 1966-1969, Artforum, February 2019, p. 164-167 REVIEWS FOCUS 166 Dan Nadel OIi "Hall)' Who? 1966-1969 " 11:18 Barry SChwabskyon Raout de Keyser 169 Dvdu l<ekeon the 12th Shangh ai Blennale NEW YORK PARIS zoe Lescaze on Liu vu,kav11ge 186 UllianOevieson Lucla L.a&una Ania Szremski on Amar Kanwar Mart1 Hoberman on Alaln Bublex Jeff Gibson on Paulina OloW5ka BERLIN 172 Colby Chamberialn on Lorraine O'Grady 187 MartinHerberton SteveBlshop OavtdFrankelon lyleAshtonHarrl5 Jurriaan Benschopon Louise Bonnet 173 MlchaelWilsonon HelenMlrra Chloe Wyma on Leonor Finl HAMBURG R11chelChumeron HeddaS1erne JensAsthoffon UllaYonBrandenburg Mira DayalonM11rcelStorr ZURICH 176 Donald Kuspit on ltya Bolotowsky Adam Jasper on Raphaela Vogel Barry Schwabsky on Gregor Hildebrandt 2ackHatfieldon"AnnaAtklns ROME Refracted: Contemporary Works " Francesca Pola on Elger Esser Sasha Frere-Jones on Aur.i Satz TURIN.ITALY Matthew Weinstein on Allen Frame Giorglo\lerzottlon F,ancescoVeuoll WASHINGTON, DC VIENNA 179 TinaR1versRyan011 TrevorPaglen Yuki Higashinoon CHICAGO Wende1ienvanO1denborgh C.C. McKee on Ebony G. Patterson PRAGUE BrienT. Leahy on Robertlostull er 192 Noemi Smolik on Jakub Jansa LISBON 181 Kaira M. cabanas on AlexandreMeloon JuanArauJo ·co ntesting Modernity : ATHENS lnlormallsm In Venezuela, 1955-1975" 193 Cathr)TI Drakeontlle 6thAthensB lennele EL PASO,TEXAS BEIJING 1s2 Che!seaweatherson 194 F!OrlB He on Zhan, Pelll "AfterPosada : Revolutlon · YuanFucaon ZhaoYao LOS ANGELES TOKYO 183 SuzanneHudsonon Sert1Gernsbecher 195 Paige K. Bradley on Lee Kil Aney Campbell on Mary Reid KalleyandP!ltflCkKelley OUBAI GollcanDamifkaz1k on Ana Mazzei TORONTO Dan Adler on Shannon Boo! ABIOJAN, IVORY COAST 196 Mars Haberman on Ouatlera Watts LONDON Sherman Sam on Lucy Dodd SAO PAULO EJisaSchaarot1Flom1Tan Camila Belchior on Clarissa Tossln CHRISTCHURCH. -

Ezra Pound His Metric and Poetry Books by Ezra Pound

EZRA POUND HIS METRIC AND POETRY BOOKS BY EZRA POUND PROVENÇA, being poems selected from Personae, Exultations, and Canzoniere. (Small, Maynard, Boston, 1910) THE SPIRIT OF ROMANCE: An attempt to define somewhat the charm of the pre-renaissance literature of Latin-Europe. (Dent, London, 1910; and Dutton, New York) THE SONNETS AND BALLATE OF GUIDO CAVALCANTI. (Small, Maynard, Boston, 1912) RIPOSTES. (Swift, London, 1912; and Mathews, London, 1913) DES IMAGISTES: An anthology of the Imagists, Ezra Pound, Aldington, Amy Lowell, Ford Maddox Hueffer, and others GAUDIER-BRZESKA: A memoir. (John Lane, London and New York, 1916) NOH: A study of the Classical Stage of Japan with Ernest Fenollosa. (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1917; and Macmillan, London, 1917) LUSTRA with Earlier Poems. (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1917) PAVANNES AHD DIVISIONS. (Prose. In preparation: Alfred A. Knopf, New York) EZRA POUND HIS METRIC AND POETRY I "All talk on modern poetry, by people who know," wrote Mr. Carl Sandburg in _Poetry_, "ends with dragging in Ezra Pound somewhere. He may be named only to be cursed as wanton and mocker, poseur, trifler and vagrant. Or he may be classed as filling a niche today like that of Keats in a preceding epoch. The point is, he will be mentioned." This is a simple statement of fact. But though Mr. Pound is well known, even having been the victim of interviews for Sunday papers, it does not follow that his work is thoroughly known. There are twenty people who have their opinion of him for every one who has read his writings with any care. -

Gladys Nilsson MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY | 523 WEST 24TH STREET

MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY 523 West 24th Street, New York,New York 10011 Tel: 212-243-0200 Fax: 212-243-0047 Gladys Nilsson MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY | 523 WEST 24TH STREET GARTH GREENAN GALLERY “Honk! Fifty Years of Painting,” an energizing, deeply satisfying pair of shows devoted to the work of Gladys Nilsson that occupied both Matthew Marks’s Twenty-Fourth Street space, where it remains on view through April 18, and Garth Greenan Gallery, took its title from one of the earliest works on display: Honk, 1964, a tiny, Technicolor street scene in acrylic that focuses on a pair of elderly couples, which the Imagist made two years out of art school. The men, bearded and stooped, lean on canes, while the women sport dark sunglasses beneath their blue-and-chartreuse beehives. They are boxed in by four more figures: Some blank-eyed and grimacing, others skulking under fedoras pulled low. The scene might suggest a vague Kastner, Jeffrey. “Gladys Nilsson.” 58, no. 8, April 2020. Artforum kind of menace were it not for the little green noisemakers dangling from the bright-red lips of the central quartet, marking them as sly revelers rather than potential victims of some unspecified mayhem. The painting’s acid palette and thickly stylized figures obviously owe a debt to Expressionism, whose lessons Nilsson thoroughly absorbed during regular museum visits in her youth, but its sensibility is more Yellow Submarine than Blaue Reiter, its grotesquerie leavened with genial good humor. The Marks portion of the show focuses primarily on the first decade of Nilsson’s career, while Greenan’s featured works made in the past few years, the two constituent parts together neatly bookending the artist’s richly varied and lamentably underappreciated oeuvre. -

Gyã¶Rgy Kepes Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c80r9v19 No online items Guide to the György Kepes papers M1796 Collection processed by John R. Blakinger, finding aid by Franz Kunst Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2016 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the György Kepes M1796 1 papers M1796 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: György Kepes papers creator: Kepes, Gyorgy Identifier/Call Number: M1796 Physical Description: 113 Linear Feet (108 boxes, 68 flat boxes, 8 cartons, 4 card boxes, 3 half-boxes, 2 map-folders, 1 tube) Date (inclusive): 1918-2010 Date (bulk): 1960-1990 Abstract: The personal papers of artist, designer, and visual theorist György Kepes. Language of Material: While most of the collection is in English, there is also a significant amount of Hungarian text, as well as printed material in German, Italian, Japanese, and other languages. Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36 hours in advance. Biographical / Historical Artist, designer, and visual theorist György Kepes was born in 1906 in Selyp, Hungary. Originally associated with Germany’s Bauhaus as a colleague of László Moholy-Nagy, he emigrated to the United States in 1937 to teach Light and Color at Moholy's New Bauhaus (soon to be called the Institute of Design) in Chicago. In 1944, he produced Language of Vision, a landmark book about design theory, followed by the publication of six Kepes-edited anthologies in a series called Vision + Value as well as several other books. -

Les Peintres Cubistes

•4 i- I i r, 1 TOUS LES ARTS COLLECTION PUBLIÉE SOUS LA DIRECTION DE M. Guillaume APOLLINAIRE GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE [Méditations Esthétiques j Les Peintres Cubistes PREMIÈRE SÉRIE Pablo PICASSO — Georges BHAQUE — Jean HETEINGER Albert GLSIZES — Jnan GRIS - Hile Harie RAURENCI H Pernand LÉGER — Francis PICABIA — Marcel DUCHAMP Dnohamp-VILLCN’, etc. OUVRAGE ACCOMPAGNÉ DE 46 PORTRAITS ET REPRODUCTIONS HORS TEXTE DEUXIÈME ÉDITION PARIS EUGÈNE FIGUIÈRE ET C‘% ÉDITEURS 7, RUE CORNEILLE, 7 MCMXIII Tous droit? résorvés pour tous i^ay> y i-oiupris In Suède, la Norvè^'C et la Uu-sie. '* \ ’à'-' 'J. m: . \ r.f- 't- Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from Duke University Libraries https://archive.org/details/lespeintrescubisOOapol Les Peintres Cubistes Il a éié tiré de cet ouvrage dix exemplaires sur Japon Impérial numérotés de i à lo. Privilège Copyright in the United-States by Guillaume Apollinaire, 20 Mars 1913. TOUS LES ARTS COLLECTION PUBLIÉE SOUS LA DIRECTION DE M. Guillaume APOLLINAIRE GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE [Méditations Esthétiques] Les Peintres Cubistes PREMIÈRE SÉRIE Pablo PICASSO — Georges BRAQUE — Jean METZINGER Albert GLEIZES — Juan GRIS — Mlle Marie RAUREHCIN Fernand LÉGER — Francis PICABIA — Marcel DUCHAMP DUCHAMP-VILLON, etc. OUVB.\GE ACCOMPAGNÉ DE 46 PORTRAITS ET REPRODUCTIONS HORS TEXTE DEUXIÈME ÉDITION PARIS EUGÈNE FIGUIÈRE ET C‘^ ÉDITEURS 7 7 , RUE CORNEILLE, MCMXIII Tous droits réservés pour tous pays y compris la Suède, la Norvège et la Russie. I '-Un* MÉDITATIONS ESTHÉTIQUES Sur la peinture I Les vertus plastiques : la pureté, l’unité et la vérité main- tiennent sous leurs pieds la nature terrassée. En vain, on bande l’arc-en-ciel, les saisons frémissent, les foules se ruent vers la mort, la science défait et refait ce qui existe, les mondes s’éloignent à jamais de notre conception, nos images mobiles se répètent ou ressuscitent leur incons- cience et les couleurs, les odeurs, les bruits qu’on mène nous étonnent, puis disparaissent de la nature. -

Gladys Nilsson Featured in the New York Times

http://nyti.ms/1n3sZC4 ART & DESIGN | ART REVIEW Recognizing a Vibrant Underground ‘What Nerve!’ at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum By KEN JOHNSON SEPT. 25, 2014 In 1962 the film critic Manny Farber published the provocative essay “White Elephant Art and Termite Art,” in which he distinguished two types of artists: the White Elephant artist, who tries to create masterpieces equal to the greatest artworks of the past, and the Termite, who engages in “a kind of squandering- beaverish endeavor” that “goes always forward, eating its own boundaries and, likely as not, leaves nothing in its path other than signs of eager, industrious, unkempt activity.” While White Elephant artists like Richard Serra, Brice Marden, Jeff Koons and a few other usually male contemporary masters still are most highly valued by the establishment, the art world’s Termite infestation has grown exponentially. They’re everywhere, male and female, busily burrowing in a zillion directions. They’re painting, drawing, doodling, whittling, tinkering and making comic books, zines, animated videos and Internet whatsits — all, it seems, with no objective other than to just keep doing whatever they’re doing. Where did they come from? How did this happen? The history of White Elephant art is well known, that of Termite art much less so, which isn’t surprising given its furtive, centerless nature. So it’s gratifying to see a rousing exhibition at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum that blocks out a significant part of what such a history would entail. “What Nerve! Alternative Figures in American Art, 1960 to the Present” presents more than 180 paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, photographs and videos by 29 artists whom Mr. -

Orpheu Et Al. Modernism, Women, and the War

Orpheu et al. Modernism, Women, and the War M. Irene Ramalho-Santos* Keywords Little magazines, Poetry, Modernism, The Great War, Society, Sexual mores. Abstract The article takes off from Orpheu, the little magazine at the origin of Portuguese modernism, to reflect, from a comparative perspective, on the development of modernist poetry in the context of the Great War and the social changes evolving during the first decades of the twentieth century on both sides of the Atlantic. Palavras-chave “Little magazines,” Poesia, Modernismo, A Grande Guerra, Sociedade, Costumes sexuais. Resumo O artigo parte de Orpheu, a revista que dá origem ao modernismo português, para reflectir, numa perspectiva comparada, soBre o desenvolvimento da poesia modernista no contexto da Grande Guerra e das mudanças sociais emergentes nas primeiras décadas do século XX dos dois lados do Atlântico. * Universidade de CoimBra; University of Wisconsin-Madison. Ramalho Santos Orpheu et al. It is frequently repeated in the relevant scholarship that Western literary and artistic modernism started in little magazines.1 The useful online Modernist Journals Project (Brown University / Tulsa University), dealing so far only with American and British magazines, uses as its epigraph the much quoted phrase: “modernism began in the magazines”, see SCHOLES and WULFMAN (2010) and BROOKER and THACKER (2009-2013). With two issues published in 1915 and a third one stopped that same year in the galley proofs for lack of funding, the Portuguese little magazine Orpheu inaugurated modernism in Portugal pretty much at the same time as all the other major little magazines in Europe and the United States. This is interesting, given the proverbial belatedness of Portuguese accomplishments, and no less interesting the fact that, like everywhere else, Orpheu was followed, in Portugal as well, By a number of other little magazines. -

A Finding Aid to the Ellen Lanyon Papers, Circa 1880-2014, Bulk 1926-2013, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Ellen Lanyon Papers, circa 1880-2014, bulk 1926-2013, in the Archives of American Art Hilary Price 2016 September 19 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1880-2015 (bulk 1926-2015)......................... 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1936-2015.................................................................. 10 Series 3: Interviews, circa 1975-2012.................................................................... 24 Series 4: Writings, Lectures, and Notebooks, circa -

Karl Wirsum B

Karl Wirsum b. 1939 Lives and works in Chicago, IL Education 1961 BFA, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL Solo Exhibitions 2019 Unmixedly at Ease: 50 Years of Drawing, Derek Eller Gallery, NY Karl Wirsum, Corbett vs Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2018 Drawing It On, 1965 to the Present, organized by Dan Nadel and Andreas Melas, Martinos, Athens, Greece 2017 Mr. Whatzit: Selections from the 1980's, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY No Dogs Aloud, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2015 Karl Wirsum, The Hard Way: Selections from the 1970s, Organized with Dan Nadel, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2013 Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Drawings: 1967-70, co-curated by Dan Nadel, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2008 Karl Wirsum: Paintings & Prints, Contemporary Art Center of Peoria, Peoria, IL Winsome Works(some), Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago, IL; traveled to Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, WI; Herron Galleries, Indiana University- Perdue University, Indianapolis, IN 2007 Karl Wirsum: Plays Missed It For You, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2006 The Wirsum-Gunn Family Show, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2005 Union Art Gallery, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI 2004 Hello Again Boom A Rang: Ten Years of Wirsum Art, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2002 Paintings and Cutouts, Quincy Art Center, Quincy, IL Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2001 Rockford College Gallery, Rockford, IL 2000 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 1998 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL University Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1997 The University of Iowa Museum of Art, Sculpture Court, Iowa City, IA 1994 Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, IL J. -

Cross-Cultural Intertextuality in Gao Xingjian's Novel Lingshair. A

LI XIA Cross-Cultural Intertextuality in Gao Xingjian's Novel Lingshair. A Chinese Perspective Gao Xingjian's novel Ungshar? (1990) has been identified by leading Western critics (the Nobel Prize Committee in particular) as one of the great works of twentieth-century Chinese literature, which has opened new paths for Chinese fiction with regard to form, structure and psychological foundation. In addition to the innovative complexity of narrative technique and linguistic ingenuity, Gao Xingjian has also been hailed a creator of distinct images of contemporary humanity and one of the few male authors artistically preoccupied with the "truth of women." While the claim concerning women is at best problematic, Gao's narrative technique as highlighted in LJngshan represents without doubt a highly artistic integration of traditional Chinese literary practice and some of the key features of Western (European) narrative technique associated by Ihab Hassan, Douwe Fokkema, Fredric Jameson, Umberto Eco, and Linda Hutcheon, among others, with postmodernist fictional discourse. As Gao left China for France in 1987, he was still present at the early debate on modernism and postmodernism among Chinese scholars and writers such as Yuan Kejia, Chen Kun, Liu Mingjiu, Wang Meng, Xu Chi, and Li Tuo, to mention only the more important ones, in the early 1980s (Wang 500-01). Due to his longstanding interest in Western literature, philosophy, and literary theory, which he studied at the Beijing Foreign Languages Institute as a French major, it is even likely that he attended Eco's, Jameson's or Fokkema's lectures at Peking University in the mid 1980s, or that 1 Lingshan has been translated into English as Soul Mountain by Mabel Lee (2000a). -

Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Spring 1992 Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism Alan Filres University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Filres, Alan, "Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism" (1992). The Courier. 293. https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc/293 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY AS SOC lATE S COURIER VOLUME XXVII, NUMBER 1, SPRING 1992 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXVII NUMBER ONE SPRING 1992 Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism By Alan Filreis, Associate Professor ofEnglish, 3 University ofPennsylvania Adam Badeau's "The Story ofthe Merrimac and the Monitor" By Robert]. Schneller,Jr., Historian, 25 Naval Historical Center A Marcel Breuer House Project of1938-1939 By Isabelle Hyman, Professor ofFine Arts, 55 New York University Traveler to Arcadia: Margaret Bourke-White in Italy, 1943-1944 By Randall I. Bond, Art Librarian, 85 Syracuse University Library The Punctator's World: A Discursion (Part Seven) By Gwen G. Robinson, Editor, Syracuse University 111 Library Associates Courier News ofthe Syracuse University Library and the Library Associates 159 Modernism from Right to Left: Wallace Stevens, the Thirties, and Radicalism BY ALAN FILREIS Author's note: In writing the bookfrom which thefollowing essay is ab stracted, I need have gone no further than the George Arents Research Li brary. -

Blanchet 18102013 Bd.Pdf

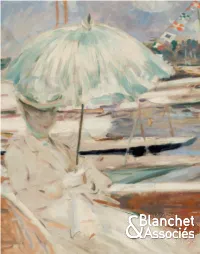

2, boulevard Montmartre - 75009 PARIS Tél. : (33)1 53 34 14 44 - Fax : (33)1 53 34 00 50 [email protected] www.blanchet-associes.com Société de ventes volontaires Agrément N°2002-212 BLANCHET ASSOCIÉS & • 18 OCTOBRE 2013 DROUOT-RICHELIEU - Salle 7 9, rue Drouot - 75009 Paris - Tél. : (33)1 48 00 20 20 - Fax : (33)1 48 00 20 33 VENDREDI 18 OCTOBRE 2013 - 14 H 30 Après succession Collection du Dr et Mme Philippe Marette IMPORTANTS TABLEAUX & SCULPTURES XIXe & XXe Première vente EXPOSITIONS PUBLIQUES À DROUOT-RICHELIEU - Salle 7 Jeudi 17 octobre 2013 l 11 h 00 à 18 h 00 Vendredi 18 octobre 2013 l 11 h 00 à 12 h 00 Téléphone pendant l’exposition et la vente : 01 48 00 20 07 Catalogue en ligne : www.blanchet-associes.com - www.gazette-drouot.com PIERRE BLANCHET & PATRICK DAYEN - COMMISSAIRES-PRISEURS ASSOCIÉS FRANCE LENAIN - DIRECTEUR ASSOCIÉ 2, boulevard Montmartre - 75009 PARIS Tél. : (33)1 53 34 14 44 - Fax : (33)1 53 34 00 50 www.blanchet-associes.com [email protected] Société de ventes volontaires Agrément N°2002-212 En couverture lot n° 52 (détail) Le Docteur et Mme Philippe Marette dans leur salon devant les Forain. Le Docteur Philippe Marette, médecin, psychiatre reconnu, frêre de Françoise Dolto, commença sa « carrière de collectionneur » vers 1932. Durant l’occupation, entre deux visites médicales à l’hôpital Bichat, il ouvrit une boutique d’antiquaire. Après 1946, son métier de médecin l’absorbant énormément, il dut quitter avec beaucoup de regrets son activité d’antiquaire, mais sans pour autant perdre son flair de collectionneur.