Working Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan Abstract In Singapore, the percentage of elected female politicians rose from 3.8 percent in 1984 to 22.5 percent after the 2015 general election. After years of exclusion, why were gender reforms adopted and how did they lead to more women in political office? Unlike South Korea and Taiwan, this paper shows that in Singapore party pragmatism rather than international diffusion of gender equality norms, feminist lobbying, or rival party pressures drove gender reforms. It is argued that the ruling People’s Action Party’s (PAP) strategic and electoral calculations to maintain hegemonic rule drove its policy u-turn to nominate an average of about 17.6 percent female candidates in the last three elections. Similar to the PAP’s bid to capture women voters in the 1959 elections, it had to alter its patriarchal, conservative image to appeal to the younger, progressive electorate in the 2000s. Additionally, Singapore’s electoral system that includes multi-member constituencies based on plurality party bloc vote rule also makes it easier to include women and diversify the party slate. But despite the strategic and electoral incentives, a gender gap remains. Drawing from a range of public opinion data, this paper explains why traditional gender stereotypes, biased social norms, and unequal family responsibilities may hold women back from full political participation. Keywords: gender reforms, party pragmatism, plurality party bloc vote, multi-member constituencies, ethnic quotas, PAP, Singapore DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5509/2016892369 ____________________ Netina Tan is an assistant professor of political science at McMaster University. -

Annex B Biographies Keynote Speaker

ANNEX B BIOGRAPHIES KEYNOTE SPEAKER: Mr GOH Chok Tong is the Senior Minister of the Republic of Singapore . He is concurrently Chairman of the Monetary Authority of Singapore . Mr Goh served as Prime Minister from November 1990 to August 2004, when he stepped aside to pave the way for political self-renewal. He was First Deputy Prime Minister between 1985 and November 1990. Mr Goh has been a member of the Singapore Cabinet since 1979, having held various portfolios including Trade and Industry, Health and Defence. Between 1977 and 1979, he was Senior Minister of State for Finance. He has been a Member of Parliament since 1976. Prior to joining politics, Mr Goh was Managing Director of Neptune Orient Lines. SINGAPORE CONFERENCE MODERATOR: Mr HO Kwon Ping is Executive Chairman of the Banyan Tree Group , which owns both listed and private companies engaged in the development, ownership and operation of hotels, resorts, spas, residen tial homes, retail galleries and other lifestyle activities in the region. Mr Ho is also Chairman of the family-owned Wah Chang Group; Chairman of Singapore Management University, the third national university in Singapore; and Chairman of MediaCorp, Singapore's national broadcaster. SINGAPORE CONFERENCE PANELLISTS: Dr LEE Boon Yang is the Minister for Information, Communications & the Arts, Republic of Singapore . He first won his seat in Parliament in the General Elections of 1984. He has since held political appointments in the Ministries of Environment, Communications & Information, Finance, Home Affairs, Trade & Industry, National Development, Defence, Prime Minister's Office and Labour/Manpower. Dr Vivian BALAKRISHNAN is the Acting Minister for Community Development, Youth & Sports and Senior Minister of State for Trade & Industry, Republic of Singapore . -

Parliamentary Debates Singapore Official Report

Volume 94 Monday No 21 11 July 2016 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SINGAPORE OFFICIAL REPORT CONTENTS Written Answers to Questions Page 1. Posting of Job Openings in Public Service on National Jobs Bank (Mr Patrick Tay Teck Guan) 1 2. Plans for Wider Use of Automated Vehicle Systems in Transport System (Dr Lim Wee Kiak) 1 3. Statistics on Malaysian Cars Entering and Leaving Singapore and Traffic Offences Committed (Mr Low Thia Khiang) 2 4. Erection of Noise Barriers between Chua Chu Kang and Bukit Gombak MRT Stations (Mr Zaqy Mohamad) 2 5. Need for Pram-friendly Buses (Mr Desmond Choo) 3 6. Review of Need for Inspection of New Cars from Third Year Onwards (Mr Ang Hin Kee) 3 7. Number of Female Bus Captains Employed by Public Bus Operators (Mr Melvin Yong Yik Chye) 4 8. Green-Man Plus Scheme at Pedestrian Crossing along Potong Pasir Avenue 1 (Mr Sitoh Yih Pin) 5 9. Determination of COE Quota for Category D Vehicles (Mr Thomas Chua Kee Seng) 5 10. Taxi Stand in Vicinity of Blocks 216 to 222 at Lorong 8 Toa Payoh (Mr Sitoh Yih Pin) 6 11. Cyber Security Measures in Place at Key Installations and Critical Infrastructures (Mr Darryl David) 6 12. Government Expenditure on Advertisements and Sponsored Posts on Online Media Platforms (Mr Dennis Tan Lip Fong) 7 13. Regulars, NSmen and NSFs Diagnosed with Mental Health Problems (Mr Dennis Tan Lip Fong) 7 14. Involvement of Phone Scam Suspects Arrested Overseas in Phone Scams in Singapore (Mr Gan Thiam Poh) 8 15. Deployment of Auxiliary Police Officers and CCTVs at Liquor Control Zone in Little India (Mr Melvin Yong Yik Chye) 9 16. -

'Citizen Journalism': Bridging the Discrepancy in Singapore's

www.ssoar.info ’Citizen Journalism’: Bridging the Discrepancy in Singapore’s General Elections News Gomez, James Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Gomez, J. (2006). ’Citizen Journalism’: Bridging the Discrepancy in Singapore’s General Elections News. Südostasien aktuell : journal of current Southeast Asian affairs, 25(6), 3-34. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-336844 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Südostasien aktuell 6/2006 3 Studie ’Citizen Journalism’: Bridging the Discrepancy in Singapore’s General Elections News James Gomez Abstract The political expression of ordinary Internet users in Singapore has received the attention of some scholars but very little has been specifically written about citizen journalism during general elections. Since the arrival of the Internet in Singapore in 1995, the People’s Action Party (PAP) government has actively sought to control the supply of online political content during the election campaign period. This paper looks at how online political expressions of ordinary Internet users and the regulations to control them have taken shape during the last three general elections in 1997, 2001 and 2006. -

1 Singapore's Dominant Party System

Tan, Kenneth Paul (2017) “Singapore’s Dominant Party System”, in Governing Global-City Singapore: Legacies and Futures after Lee Kuan Yew, Routledge 1 Singapore’s dominant party system On the night of 11 September 2015, pundits, journalists, political bloggers, aca- demics, and others in Singapore’s chattering classes watched in long- drawn amazement as the media reported excitedly on the results of independent Singa- pore’s twelfth parliamentary elections that trickled in until the very early hours of the morning. It became increasingly clear as the night wore on, and any optimism for change wore off, that the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) had swept the votes in something of a landslide victory that would have puzzled even the PAP itself (Zakir, 2015). In the 2015 general elections (GE2015), the incumbent party won 69.9 per cent of the total votes (see Table 1.1). The Workers’ Party (WP), the leading opposition party that had five elected members in the previous parliament, lost their Punggol East seat in 2015 with 48.2 per cent of the votes cast in that single- member constituency (SMC). With 51 per cent of the votes, the WP was able to hold on to Aljunied, a five-member group representation constituency (GRC), by a very slim margin of less than 2 per cent. It was also able to hold on to Hougang SMC with a more convincing win of 57.7 per cent. However, it was undoubtedly a hard defeat for the opposition. The strong performance by the PAP bucked the trend observed since GE2001, when it had won 75.3 per cent of the total votes, the highest percent- age since independence. -

331KB***Administrative and Constitutional

(2016) 17 SAL Ann Rev Administrative and Constitutional Law 1 1. ADMINISTRATIVE AND CONSTITUTIONAL LAW THIO Li-ann BA (Oxon) (Hons), LLM (Harvard), PhD (Cantab); Barrister (Gray’s Inn, UK); Provost Chair Professor, Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore. Introduction 1.1 In terms of administrative law, the decided cases showed some insight into the role of courts in relation to: handing over town council management to another political party after a general election, the susceptibility of professional bodies which are vested with statutory powers like the Law Society review committee to judicial review; as well as important observations on substantive legitimate expectations and developments in exceptions to the rule against bias on the basis of necessity, and how this may apply to private as opposed to statutory bodies. Many of the other cases affirmed existing principles of administrative legality and the need for an evidential basis to sustain an argument. For example, a bare allegation of bias without evidence cannot be sustained; allegations of bias cannot arise when a litigant is simply made to follow well-established court procedures.1 1.2 Most constitutional law cases revolved around Art 9 issues. Judicial observations on the nature or scope of specific constitutional powers were made in cases not dealing directly with constitutional arguments. See Kee Oon JC in Karthigeyan M Kailasam v Public Prosecutor2 noted the operation of a presumption of legality and good faith in relation to acts of public officials; the Prosecution, in particular, is presumed “to act in the public interest at all times”, in relation to all prosecuted cases from the first instance to appellate level. -

Institutionalized Leadership: Resilient Hegemonic Party Autocracy in Singapore

Institutionalized Leadership: Resilient Hegemonic Party Autocracy in Singapore By Netina Tan PhD Candidate Political Science Department University of British Columbia Paper prepared for presentation at CPSA Conference, 28 May 2009 Ottawa, Ontario Work- in-progress, please do not cite without author’s permission. All comments welcomed, please contact author at [email protected] Abstract In the age of democracy, the resilience of Singapore’s hegemonic party autocracy is puzzling. The People’s Action Party (PAP) has defied the “third wave”, withstood economic crises and ruled uninterrupted for more than five decades. Will the PAP remain a deviant case and survive the passing of its founding leader, Lee Kuan Yew? Building on an emerging scholarship on electoral authoritarianism and the concept of institutionalization, this paper argues that the resilience of hegemonic party autocracy depends more on institutions than coercion, charisma or ideological commitment. Institutionalized parties in electoral autocracies have a greater chance of survival, just like those in electoral democracies. With an institutionalized leadership succession system to ensure self-renewal and elite cohesion, this paper contends that PAP will continue to rule Singapore in the post-Lee era. 2 “All parties must institutionalize to a certain extent in order to survive” Angelo Panebianco (1988, 54) Introduction In the age of democracy, the resilience of Singapore’s hegemonic party regime1 is puzzling (Haas 1999). A small island with less than 4.6 million population, Singapore is the wealthiest non-oil producing country in the world that is not a democracy.2 Despite its affluence and ideal socio- economic prerequisites for democracy, the country has been under the rule of one party, the People’s Action Party (PAP) for the last five decades. -

Jaclyn L. Neo

Jaclyn L. Neo NAVIGATING MINORITY INCLUSION AND PERMANENT DIVISION: MINORITIES AND THE DEPOLITICIZATION OF ETHNIC DIFFERENCE* INTRODUCTION dapting the majority principle in electoral systems for the ac- commodation of political minorities is a crucial endeavour if A one desires to prevent the permanent disenfranchisement of those minorities. Such permanent exclusion undermines the maintenance and consolidation of democracy as there is a risk that this could lead to po- litical upheaval should the political minorities start to see the system as op- pressive and eventually revolt against it. These risks are particularly elevat- ed in the case of majoritarian systems, e.g. those relying on simple plurality where the winner is the candidate supported by only a relative majority, i.e. having the highest number of votes compared to other candidates1. Further- more, such a system, while formally equal, could however be considered substantively unequal since formal equality often fails to recognize the es- pecial vulnerabilities of minority groups and therefore can obscure the need to find solutions to address those vulnerabilities. Intervention in strict majoritarian systems is thus sometimes deemed necessary to preserve effective participation of minorities in political life to ensure a more robust democracy. Such intervention has been considered es- pecially important in societies characterized by cleavages such as race/ethnicity, religion, language, and culture, where there is a need to en- sure that minority groups are not permanently excluded from the political process. This could occur when their voting choices almost never produce the outcomes they desire or when, as candidates, they almost never receive the sufficient threshold of support to win elections. -

Speech by Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong at The

SPEECH BY SENIOR MINISTER GOH CHOK TONG AT THE CONFERMENT OF HONORARY MEMBERSHIP BY THE SINGAPORE MEDICAL ASSOCIATION (SMA), AT SMA ANNUAL DINNER HELD ON SATURDAY, 27 MAY 2006, AT 7.30 PM AT THE ROYAL BALLROOM, REGENT HOTEL Distinguished Guests and Friends A very good evening to you all. Thank you, Vivian, for your warm and kind words. I happened to be in the right place at the right time. Many of the achievements which you attributed to me actually belonged to others - the staff and doctors in MOH, for example. And my ideas could not have been realised without the hard work of the officials who fleshed them out and implemented them. Take for instance, Medisave. Khaw Boon Wan, guided by Andrew Chew, then PS (Health), crunched the numbers and turned concepts into programmes. 2 I thank also the Singapore Medical Association (SMA) for conferring the Honorary Membership on me. This is an unexpected honour and in a sense, ironic, for I went against the flow and chose to do Economics instead of Medicine. Many of my close friends, like Tan Cheng Bock, are doctors and members of your Association. I take it that I can now rub shoulders with them in the same august Association. 3 As Vivian mentioned, I was Minister for Health a long time ago. Singapore’s healthcare sector has come a long way since then. As Prime Minister, I took an active interest in formulating our national health plans and promoting healthy living amongst Singaporeans because good health, like good education and good housing, is a key requirement for happiness and progress. -

What Singaporean Female Politicians Choose to Say in Parliament

REFLEXIONEN ZU GENDER UND POLITISCHER PARTIZIPATION IN ASIEN Mirza, Naeem/Wagha, Wasim, 2010: Performance of Women Parliamentarians in the 12th Natio- nal Assembly (2002-2007). Islamabad. Musharraf, Pervez, 2006: In the Line of Fire. London. Mustafa, Zubeida, 2009: Where Were You, Dear Sisters? In: Dawn, 22.04.2009. Navarro, Julien, 2009: Les députés européens et leur rôle. Bruxelles. Phillips, Anne, 1995: The Politics of Presence. Oxford. PILDAT, 2002: Directory of the Members of the 12th National Assembly of Pakistan. Islamabad. Pitkin, Hanna F., 1967: The Concept of Representation. Berkeley. Rehfeld, Andrew, 2005: The Concept of Constituency. Political Representation, Democratic Legi- timacy, and Institutional Design. New York. Searing, Donald, 1994: Westminster’s World. Understanding Political Roles. Cambridge (Mass.). Shafqat, Saeed, 2002: Democracy and Political Transformation in Pakistan. In: Mumtaz, Soofia, Racine, Jean-Luc, Ali Imran, Anwar (eds.): Pakistan. The Contours of State and Society. Karachi, 209-235. Siddiqui, Niloufer, 2010: Gender Ideology and the Jamaat-e-Islami. In: Current Trends in Islamist Ideology. Vol. 10. Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty, 1988 (1985): Subaltern Studies. Deconstructing Historiography. In: Guha, Ranajit/Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty (eds.). Subaltern Studies. New York, 3-32. Solberg, Kristin Elisabeth, 2010: New Laws Could Improve Women’s Health in Pakistan. In: The Lancet. 975 (9730), 1956. Special Committee on Constitutional Reform, 2010: Report. Islamabad. Talbot, Ian, 2005: Pakistan. A Modern History. London. UNDP, 2005: Political and legislative participation of women in Pakistan: Issues and perspectives. Weiss, Anita, 2001: Gendered Power Relations. Perpetuation and Renegotiation. In: Weiss Anita/ Gilani Zulfikar (eds.): Power and Civil Society in Pakistan. Oxford, 65-89. Yasin, Asim, 2007: Discord over PPP tickets for women’s seats. -

Lee Kuan Yew V Chee Soon Juan (No 2)

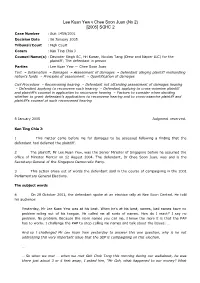

Lee Kuan Yew v Chee Soon Juan (No 2) [2005] SGHC 2 Case Number : Suit 1459/2001 Decision Date : 06 January 2005 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Kan Ting Chiu J Counsel Name(s) : Davinder Singh SC, Hri Kumar, Nicolas Tang (Drew and Napier LLC) for the plaintiff; The defendant in person Parties : Lee Kuan Yew — Chee Soon Juan Tort – Defamation – Damages – Assessment of damages – Defendant alleging plaintiff mishandling nation's funds – Principles of assessment – Quantification of damages Civil Procedure – Reconvening hearing – Defendant not attending assessment of damages hearing – Defendant applying to reconvene such hearing – Defendant applying to cross-examine plaintiff and plaintiff's counsel in application to reconvene hearing – Factors to consider when deciding whether to grant defendant's applications to reconvene hearing and to cross-examine plaintiff and plaintiff's counsel at such reconvened hearing 6 January 2005 Judgment reserved. Kan Ting Chiu J: 1 This matter came before me for damages to be assessed following a finding that the defendant had defamed the plaintiff. 2 The plaintiff, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, was the Senior Minister of Singapore before he assumed the office of Minister Mentor on 12 August 2004. The defendant, Dr Chee Soon Juan, was and is the Secretary-General of the Singapore Democratic Party. 3 This action arose out of words the defendant said in the course of campaigning in the 2001 Parliamentary General Elections. The subject words 4 On 28 October 2001, the defendant spoke at an election rally at Nee Soon Central. He told his audience: Yesterday, Mr Lee Kuan Yew was at his best. -

BTI 2014 | Singapore Country Report

BTI 2014 | Singapore Country Report Status Index 1-10 7.22 # 24 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 5.55 # 68 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 8.89 # 6 of 129 Management Index 1-10 5.98 # 35 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2014. It covers the period from 31 January 2011 to 31 January 2013. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014 — Singapore Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2014 | Singapore 2 Key Indicators Population M 5.3 HDI 0.895 GDP p.c. $ 61803.2 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 2.5 HDI rank of 187 18 Gini Index - Life expectancy years 81.9 UN Education Index 0.804 Poverty3 % - Urban population % 100.0 Gender inequality2 0.101 Aid per capita $ - Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2013. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary Despite having weathered the financial crisis, the People’s Action Party (PAP) suffered its worst election results ever in the 2011 parliamentary election, receiving a comparatively low share of the popular vote (60%). The opposition, which had been emboldened and was more unified than ever, was also able to garner its highest ever share of seats.