Fred Goodman. Allen Klein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Paul Mccartney V Sony ATV Music Publishing

Case 1:17-cv-00363 Document 1 Filed 01/18/17 Page 1 of 16 MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP EASTMAN & EASTMAN Michael A. Jacobs (pro hac vice motion forthcoming) John L. Eastman (pro hac vice motion Roman Swoopes (pro hac vice motion forthcoming) forthcoming) 425 Market Street Lee V. Eastman (pro hac vice motion San Francisco, California 94105-2482 forthcoming) 415.268.7000 39 West 54th St New York, New York 10019 MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP 212.246.5757 J. Alexander Lawrence 250 West 55th Street New York, New York 10019-9601 212.468.8000 Paul Goldstein (pro hac vice motion forthcoming) 559 Nathan Abbott Way Stanford, California 94305-8610 650.723.0313 Attorneys for Plaintiff James Paul McCartney UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------------------------------------ x : Case No. 17cv363 JAMES PAUL MCCARTNEY, an individual, : : Plaintiff, : : Complaint for Declaratory -v.- : Judgment : SONY/ATV MUSIC PUBLISHING LLC, a : Demand for Jury Trial Delaware Limited Liability Company, and : SONY/ATV TUNES LLC, a Delaware Limited : Liability Company, : Defendants. ------------------------------------------------------------------ x COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY JUDGMENT Plaintiff James Paul McCartney, for his complaint against Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC and Sony/ATV Tunes LLC, alleges as follows: Case 1:17-cv-00363 Document 1 Filed 01/18/17 Page 2 of 16 NATURE OF THIS ACTION 1. This action involves ownership interests in the copyrights for certain musical works that Plaintiff Sir James Paul McCartney (known professionally as Paul McCartney) authored or co-authored with other former members of the world-famous musical group The Beatles. Defendants in this action are music publishing companies that claim to be the successors to publishers that acquired copyright interests in many of Paul McCartney’s compositions in the 1960s and early 1970s. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

50Th Anniversary Celebration: 1960S Music & Musical Artists Display

Clemson University TigerPrints Presentations University Libraries 12-2016 50th Anniversary Celebration: 1960s Music & Musical Artists Display Maggie Mason Smith Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Mason Smith, Maggie, "50th Anniversary Celebration: 1960s Music & Musical Artists Display" (2016). Presentations. 99. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres/99 This Display is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presentations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1960s Music & Musical Artists Display December 2016 1960s Music & Musical Artists Display Photograph taken by Micki Reid, Cooper Library Public Information Coordinator Display Description The final 50th Anniversary book display features 1960s music and musical artists. Genres featured include British Invasion; Motown/R&B; Surf, Psychedelic, Roots, Hard, and Folk Rock and protest music. Formats include print, DVD, and CD. Come to Cooper to read about, watch, or listen to The Beatles, Aretha Franklin, The Beach Boys, Janis Joplin, and Bob Dylan (among many others!) before the holidays. The display will be up throughout December and items on display can be checked out at the Library Services Desk. - Posted on Clemson University Libraries’ Blog, December 2nd 2016 Music on Display • Armstrong, Louis. The Definitive Collection. Hip-O/Verve, 2006. CD. M1630.18.A76D34 2006. • The Beatles. Abbey Road. Parlophone, 1987. CD. M1741.18.B34A23 1987. • ---. The Beatles. Parlophone, 1987. CD. M1741.18.B34B33 1987. • ---. The Beatles 1962-1966. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Sam Cooke.Pptx

Sam Cooke Group 5: Michael Muradian, Vinh Dang, Yazan Alkhatib http://assets.rollingstone.com/assets/images/artists/304x304/sam-cooke.jpg Sam Cooke Overview • Commonly referred as the "King of Soul" • Famous black gospel, soul, R&B, and pop singer and songwriter o Considered a pioneer/founder of soul music • Created 29, top 40 hits during his musical career (1957-1964) o most famous songs include: "You Send Me," "Chain Gang," and "A Change is Gonna Come" • Among first black performers to develop business side of musical career o founded a record label, and publishing company Sam Cooke Overview • Active in African-American Civil Rights Movement • Cooke's life was abruptly ended at the young age of 33 (December 11, 1964) o Cooke was fatally shot while drunk by a hotel manager in Los Angeles o Controversial • Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986 Early Life • Born on January 22nd, 1931 in Clarksdale, Mississippi • One of eight children born to Charles Cook Sr., and Annie May Cook o Father was a traveling minister of Baptist faith • Born with the name Samuel Cook, but later developed stage name of Sam Cooke • Attended Wendell Phillips Academy High School in Chicago Development of Musical Career • Began career at nine years old in the group, "The Singing Children" o sang with siblings • Sang for the "Highway QC's" at age 15 • Became lead singer in "The Soul Stirrers" o introduced revolutionary two- lead singing o gospel group attracted younger crowds due to good looks o signed with Specialty Records o songs include "Jesus Gave Me Water," "Peace in the Valley," "Jesus Paid the Debt" Sam Cooke's Musical Style • Considered to have been unique. -

Student's Project Brings Science Olympiad

Ljjp a?>* x I w,- P®^ ' !• &.: fy-i: •I mMm lyMMw va"? : -,•: ; * • • ;; HNffH 9 iPM, • •1 —apEpf—_. : hfefc,:: ;•; ;•!;;> & ifl iigs • ®!i i •• ,-'" ' I m--: y: Ittf ii . * &"'"j 1916 f'i: [- ii •m •- '4 vl 18 ARC YOU THREATENING US?! JANUARY 24,1997 game be at the game. 1, W9(>. The instances cited by the and potentially harm the name of Vikki Otero David Gordon "If they get enough mail, there alleged victim included repeated the university, the football team or Features Ediun •Ivwn f t.'nIurc\ t~.ilitot is a possibility that. IHck Vitale poking, pulling her hair, threaten the male student, she said. will switch over and call our ing bodily.injury and threatening to Throughout the investigation, Student Association External game," Klein said. A Rice football player has been kill her. The ongoing behavior, she the accused was restricted from cam Vice President Charles Klein is Klein, along with Sid suspended for the spring semester said, had its effects. pus except to attend class, lunch spearheading a campaign to bring Richardson College senior Josh after the University Court found him and football practice and games. ESPN basketball announcer Dick Earnest, spoke to Head Coach guilty on charges of assault. The According to the accuser, however, Vitale-to Rice to call the Feb",'u24 Willis Wilson in November be- charges were filed by a fellow stu- ' Rice doys everything it the restriction was not enforced and game between Rice and the Uni- fore the season started. They dent with the Rice University Police he continued to contact her during versity of Utah. -

The Racialization of Jimi Hendrix Marcus K

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2007 The Racialization of Jimi Hendrix Marcus K. Adams Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Adams, Marcus K., "The Racialization of Jimi Hendrix" (2007). Senior Honors Theses. 23. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/23 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. The Racialization of Jimi Hendrix Abstract The period of history immediately following World War Two was a time of intense social change. The nde of colonialism, the internal struggles of newly emerging independent nations in Africa, social and political changes across Europe, armed conflict in Southeast Asia, and the civil rights movement in America were just a few. Although many of the above conflicts have been in the making for quite some time, they seemed to unite to form a socio-political cultural revolution known as the 60s, the effects of which continues to this day. The 1960s asw a particularly intense time for race relations in the United States. Long before it officially became a republic, in matters of race, white America collectively had trouble reconciling what it practiced versus what it preached. Nowhere is this racial contradiction more apparent than in the case of Jimi Hendrix. Jimi Hendrix is emblematic of the racial ideal and the racial contradictions of the 1960s. -

A Change Is Gonna Come

A CHANGE IS GONNA COME: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BENEFITS OF MUSICAL ACTIVISM IN THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT By ERIN NICOLE NEAL A Capstone submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Liberal Studies Written under the direction of Dr. Stuart Z. Charmé And approved by ____________________________________ Dr. Stuart Z. Charmé Camden, New Jersey January 2021 CAPSTONE ABSTRACT A Change Is Gonna Come: A Critical Analysis Of The Benefits Of Musical Activism In The Civil Rights Movement by ERIN NICOLE NEAL Capstone Director: Dr. Stuart Z. Charmé The goal of this Capstone project is to understand what made protest music useful for political activists of the Civil Rights Movement. I will answer this question by analyzing music’s effect on activists through an examination of the songs associated with the movement, regarding lyrical content as well as its musical components. By examining the lyrical content, I will be evaluating how the lyrics of protest songs were useful for the activists, as well as address criticisms of the concrete impact of song lyrics of popular songs. Furthermore, examining musical components such as genre will assist in determining if familiarity in regards to the genre were significant. Ultimately, I found that music was psychologically valuable to political activists because music became an outlet for emotions they held within, instilled within listeners new emotions, became a beacon for psychological restoration and encouragement, and motivated listeners to carry out their activism. Furthermore, from a political perspective, the lyrics brought attention to the current socio-political problems and challenged social standards, furthered activists’ political agendas, persuaded the audience to take action, and emphasized blame on political figures by demonstrating that socio-political problems citizens grappled with were due to governmental actions as well as their inactions. -

How the Rolling Stones Amassed a Fortune Where Others Have Failed

How the Rolling Stones Amassed a Fortune Where Others Have Failed Last week Mick Jagger shared some video of his cardio workout routine. There he was dancing and moving to the music like only Mick can. Jagger was showing the world that, despite recent heart surgery, he is not slowing down. After years of hard touring and the excesses of the rock and roll lifestyle, Mick, Keith, and the rest of the Stones remain vital. During decades of near constant work, during which many of their contemporaries have failed, they have amassed fortunes. I described their investing process back in January of 2003. I wrote: Geezers in Wheelchairs… This year is the 40th anniversary of the world’s greatest rock & roll band—the Rolling Stones. Grizzled but game, the Stones truck on with their 15th North American tour. “Always precocious, the Stones at 60 look a lot like Segovia at 90: Keep the morgue on standby,” wrote the very funny Joe Queenan in the WSJ. The Stones are big business, real big business. As Fortune noted in its recent cover story, “The Stones have made more money than U2, or Springsteen, or Michael Jackson…or the Who—or whoever.” The topgrossing North American tour of all time was the Stones’ 1994 Voodoo Lounge tour. With a gross of over $120 million, these guys know how to make money and how to keep it. Jagger went to the London School of Economics. For me and perhaps for you, the really big news on the Stones is the recent hybrid (two layers) SACD release of the band’s pre-1971 material owned by Allen Klein and his ABKCO Records (the Stones’ longtime early label). -

90'S Medley Rihanna Medley Motown Medley Prince

Adele - Rolling in the Deep Jackson 5 - ABC Outkast - Miss Jackson 90’S MEDLEY Alabama Shakes - Hold on James Brown - Get Up Oa That Thing Outkast - Rosa Parks TLC Alicia Keys - Empire State of Mind James and Bobby Purify - Shake A Tail Feather Patrice Ruschen - Forget Me Nots Usher Alicia Keys - If I Ain’t Got You James Blake - Limit To Your Love Percy Sledge - You Really Got a Hold On Me Montell Jordan Al Green - Let’s Stay Together Jamie XX - Good Times Pharrell – Happy Mark Morrison Al Green - Take Me to the River Janelle Monae - Tightrope Prince – I Wanna Be Your Lover Next Amy Whinehouse - Valerie Jerry Lee Lewis - Great Balls of Fire Prince - Kiss Beck – Where It’s At Justin Timberlake - Can’t Stop The Feeling Ray Charles - Georgia Beyonce – Crazy In Love Justin Timberlake - Rock Your Body R Kelly - Remix to Ignition RIHANNA MEDLEY Beyonce - Love on Top King Harvest - Dancing in the Moonlight Sade - By Your Side What’s My Name Beyonce - Party Kendrick Lamar – If These Walls Could Talk Sade - Smooth Operator We Found Love Bill Withers - Ain’t No Sunshine Leon Bridges - Coming Home Sade - Sweetest Taboo Work Blondie – Rapture Lil Nas X - Old Town Road Sam Cooke - Wonderful World Blood Orange - You’re Not Good Enough Sam Cooke - Cupid Lionel Richie - All Night Long MOTOWN MEDLEY Bob Carlisle/Je Carson - Butterfly Kisses Little Richard - Good Golly Miss Molly Sam Cooke - Twistin’ Your Love Keeps Lifting Me Higher and Higher Bruno Mars - 24k Magic Lizzo - Juice Sam Cooke – You Send Me You Really Got a Hold On Me Bruno Mars - Treasure -

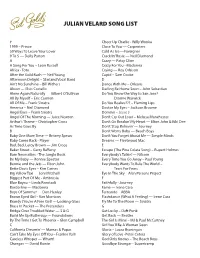

Julian Velard Song List

JULIAN VELARD SONG LIST # Cheer Up Charlie - Willy Wonka 1999 – Prince Close To You — Carpenters 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Cold As Ice —Foreigner 9 To 5 — Dolly Parton Cracklin’ Rosie — Neil Diamond A Crazy — Patsy Cline A Song For You – Leon Russell Crazy For You - Madonna Africa - Toto Crying — Roy Orbison After the Gold Rush — Neil Young Cupid – Sam Cooke Afternoon Delight – Starland Vocal Band D Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill Withers Dance With Me – Orleans Alison — Elvis Costello Darling Be Home Soon – John Sebastian Alone Again Naturally — Gilbert O’Sullivan Do You Know the Way to San Jose? — All By Myself – Eric Carmen Dionne Warwick All Of Me – Frank Sinatra Do You Realize??? – Flaming Lips America – Neil Diamond Doctor My Eyes – Jackson Browne Angel Eyes – Frank Sinatra Domino – Jesse J Angel Of The Morning — Juice Newton Don’t Cry Out Loud – Melissa Manchester Arthur’s Theme – Christopher Cross Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart — Elton John & Kiki Dee As Time Goes By Don’t Stop Believin’ — Journey B Don’t Worry Baby — Beach Boys Baby One More Time — Britney Spears Don’t You Forget About Me — Simple Minds Baby Come Back - Player Dreams — Fleetwood Mac Bad, Bad, Leroy Brown — Jim Croce E Baker Street – Gerry Raerty Escape (The Pina Colata Song) – Rupert Holmes Bare Necessities - The Jungle Book Everybody’s Talkin’ — Nilsson Be My Baby — Ronnie Spector Every Time You Go Away – Paul Young Bennie and the Jets — Elton John Everybody Wants To Rule The World – Bette Davis Eyes – Kim Carnes Tears For Fears Big Yellow Taxi — Joni Mitchell Eye In -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964