01092014-GUT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diagnosis and Treatment of Perianal Crohn Disease: NASPGHAN Clinical Report and Consensus Statement

CLINICAL REPORT Diagnosis and Treatment of Perianal Crohn Disease: NASPGHAN Clinical Report and Consensus Statement ÃEdwin F. de Zoeten, zBrad A. Pasternak, §Peter Mattei, ÃRobert E. Kramer, and yHoward A. Kader ABSTRACT disease. The first description connecting regional enteritis with Inflammatory bowel disease is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the perianal disease was by Bissell et al in 1934 (2), and since that time gastrointestinal tract that includes both Crohn disease (CD) and ulcerative perianal disease has become a recognized entity and an important colitis. Abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and weight loss consideration in the diagnosis and treatment of CD. Perianal characterize both CD and ulcerative colitis. The incidence of IBD in the Crohn disease (PCD) is defined as inflammation at or near the United States is 70 to 150 cases per 100,000 individuals and, as with other anus, including tags, fissures, fistulae, abscesses, or stenosis. autoimmune diseases, is on the rise. CD can affect any part of the The symptoms of PCD include pain, itching, bleeding, purulent gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus and frequently will include discharge, and incontinence of stool. perianal disease. The first description connecting regional enteritis with perianal disease was by Bissell et al in 1934, and since that time perianal INCIDENCE AND NATURAL HISTORY disease has become a recognized entity and an important consideration in the Limited pediatric data describe the incidence and prevalence diagnosis and treatment of CD. Perianal Crohn disease (PCD) is defined as of PCD. The incidence of PCD in the pediatric age group has been inflammation at or near the anus, including tags, fissures, fistulae, abscesses, estimated to be between 13.6% and 62% (3). -

Plugs for Anal Fistula Repair Original Policy Date: November 26, 2014 Effective Date: January 1, 2021 Section: 7.0 Surgery Page: Page 1 of 12

Medical Policy 7.01.123 Plugs for Anal Fistula Repair Original Policy Date: November 26, 2014 Effective Date: January 1, 2021 Section: 7.0 Surgery Page: Page 1 of 12 Policy Statement Biosynthetic fistula plugs, including plugs made of porcine small intestine submucosa or of synthetic material, are considered investigational for the repair of anal fistulas. NOTE: Refer to Appendix A to see the policy statement changes (if any) from the previous version. Policy Guidelines There is a specific CPT code for the use of these plugs in the repair of an anorectal fistula: • 46707: Repair of anorectal fistula with plug (e.g., porcine small intestine submucosa [SIS]) Description Anal fistula plugs (AFPs) are biosynthetic devices used to promote healing and prevent the recurrence of anal fistulas. They are proposed as an alternative to procedures including fistulotomy, endorectal advancement flaps, seton drain placement, and use of fibrin glue in the treatment of anal fistulas. Related Policies • N/A Benefit Application Benefit determinations should be based in all cases on the applicable contract language. To the extent there are any conflicts between these guidelines and the contract language, the contract language will control. Please refer to the member's contract benefits in effect at the time of service to determine coverage or non-coverage of these services as it applies to an individual member. Some state or federal mandates (e.g., Federal Employee Program [FEP]) prohibits plans from denying Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved technologies as investigational. In these instances, plans may have to consider the coverage eligibility of FDA-approved technologies on the basis of medical necessity alone. -

Surgery for Colon and Rectal Cancer

Colon and Rectal Surgery Mohammed Bayasi, MD Department of Surgery Colon and Rectal Surgery What is a Colon and Rectal Surgeon? • Fully trained General Surgeon. • Has done additional training in the diseases of colon and rectum. Why Colon and Rectal Surgery? • Surgical and non surgical therapy for multiple diseases. • Chance to help cancer patients by removing tumor, potentially curing them. • Variety of cases, ages and patient populations. • Specialized area. Colorectal Diseases • Colon • Rectum/Anus – Cancer – Hemorrhoids – Diverticulitis – Anal fistula and – Inflammatory Bowel abscess Disease (Crohn, UC) – Anal fissure – Polyps – Prolapse Symptoms/Signs • Pain • Itching • Discharge • Bleeding • Lump Anatomy Lesson Colon • Extracts water and nutrients. • Helps to form and excrete waste. • Stores important bacteria flora. • Length: 1.5 meters long = 4.9 feet = 59 inches Colon Rectum/Anus • The final portion of the colon. • Area contains muscles important in controlling defecation and flatulence. Rectum/Anus When to see a Colon and Rectal Surgeon • Referral from another physician (Gastroenterology, PCP). • Treatment of anorectal diseases. • Blood with stool, abdominal pain, rectal pain. Hemorrhoids • Internal and external. • Cushions of blood vessels. • When enlarged, they cause bleeding and pain. Treatment • Treatment of symptomatic hemorrhoids is directed by the symptoms themselves. It can broadly be categorized into four groups: − Medical therapy − Office-based procedure − Operative therapies − Emergent interventions Anorectal Abscess • It is a collection of pus in the perianal area. Normal • Causes pain and rectal gland drainage, and if it progresses, fever and systemic Abscess infection. • Treated with incision and drainage. Anorectal Fistula • A tunnel between the inside of the anus and the skin. • Causes discharge, pain, and formation of abscess. -

Common Anorectal Conditions

TurkJMedSci 34(2004)285-293 ©TÜB‹TAK PERSPECTIVESINMEDICALSCIENCES CommonAnorectalConditions PravinJ.GUPTA ConsultingProctologistGuptaNursingHome,D/9,Laxminagar,NAGPUR-440022INDIA Received:July12,2004 Anorectaldisordersincludeadiversegroupof dentateorpectinatelinedividesthesquamousepithelium pathologicdisordersthatgeneratesignificantpatient fromthemucosalorcolumnarepithelium.Fourtoeight discomfortanddisability.Althoughthesearefrequently analglandsdrainintothecryptsofMorgagniatthelevel encounteredingeneralmedicalpractice,theyoften ofthedentateline.Mostrectalabscessesandfistulae receiveonlycasualattentionandtemporaryrelief . originateintheseglands.Thedentatelinealsodelineates Diseasesoftherectumandanusarecommon theareawheresensoryfibersend.Abovethedentate phenomena.Theirprevalenceinthegeneralpopulationis line,therectumissuppliedbystretchnervefibers,and probablymuchhigherthanthatseeninclinicalpractice, notpainnervefibers.Thisallowsmanysurgical sincemostpatientswithsymptomsreferabletothe procedurestobeperformedwithoutanesthesiaabovethe anorectumdonotseekmedicalattention. dentateline.Conversely,belowthedentateline,thereis extremesensitivity,andtheperianalareaisoneofthe Asdoctorsoffirstcontact,general(family) mostsensitiveareasofthebody.Theevacuationofbowel practitioners(GPs)frequentlyfacedifficultquestions contentsdependsonactionbythemusclesofboththe concerningtheoptimummanagementofanorectal involuntaryinternalsphincterandthevoluntaryexternal symptoms.Whiletheexaminationanddiagnosisof sphincter. certainanorectaldisorderscanbechallenging,itisa -

Crohn's Disease of the Anal Region

Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.6.6.515 on 1 December 1965. Downloaded from Gut, 1965, 6, 515 Crohn's disease of the anal region B. K. GRAY, H. E. LOCKHART-MUMMERY, AND B. C. MORSON From the Research Department, St. Mark's Hospital, London EDITORIAL SYNOPSIS This paper records for the first time the clinico-pathological picture of Crohn's disease affecting the anal canal. It has long been recognized that anal lesions may precede intestinal Crohn's disease, often by some years, but the specific characteristics of the lesion have not hitherto been described. The differential diagnosis is discussed in detail. In a previous report from this hospital (Morson and types of anal lesion when the patients were first seen Lockhart-Mummery, 1959) the clinical features and were as follows: pathology of the anal lesions of Crohn's disease were described. In that paper reference was made to Anal fistula, single or multiple .............. 13 several patients with anal fissures or fistulae, biopsy Anal fissures ........... ......... 3 of which showed a sarcoid reaction, but in whom Anal fissure and fistula .................... 3 there was no clinical or radiological evidence of Total 19 intra-abdominal Crohn's disease. The opinion was expressed that some of these patients might later The types of fistula included both low level and prove to have intestinal pathology. This present complex high level varieties. The majority had the contribution is a follow-up of these cases as well as clinical features described previously (Morson and of others seen subsequently. Lockhart-Mummery, 1959; Lockhart-Mummery Involvement of the anus in Crohn's disease has and Morson, 1964) which suggest Crohn's disease, http://gut.bmj.com/ been seen at this hospital in three different ways: that is, the lesions had an indolent appearance with 1 Patients who presented with symptoms of irregular undermined edges and absence of indura- intestinal Crohn's disease who, at the same time, ation. -

Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Anorectal Abscess, Fistula-In-Ano, and Rectovaginal Fistula Jon D

PRACTICE GUIDELINES Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Anorectal Abscess, Fistula-in-Ano, and Rectovaginal Fistula Jon D. Vogel, M.D. • Eric K. Johnson, M.D. • Arden M. Morris, M.D. • Ian M. Paquette, M.D. Theodore J. Saclarides, M.D. • Daniel L. Feingold, M.D. • Scott R. Steele, M.D. Prepared on behalf of The Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons he American Society of Colon and Rectal Sur- and submucosal locations.7–11 Anorectal abscess occurs geons is dedicated to ensuring high-quality pa- more often in males than females, and may occur at any Ttient care by advancing the science, prevention, age, with peak incidence among 20 to 40 year olds.4,8–12 and management of disorders and diseases of the co- In general, the abscess is treated with prompt incision lon, rectum, and anus. The Clinical Practice Guide- and drainage.4,6,10,13 lines Committee is charged with leading international Fistula-in-ano is a tract that connects the perine- efforts in defining quality care for conditions related al skin to the anal canal. In patients with an anorec- to the colon, rectum, and anus by developing clinical tal abscess, 30% to 70% present with a concomitant practice guidelines based on the best available evidence. fistula-in-ano, and, in those who do not, one-third will These guidelines are inclusive, not prescriptive, and are be diagnosed with a fistula in the months to years after intended for the use of all practitioners, health care abscess drainage.2,5,8–10,13–16 Although a perianal abscess workers, and patients who desire information about the is defined by the anatomic space in which it forms, a management of the conditions addressed by the topics fistula-in-ano is classified in terms of its relationship to covered in these guidelines. -

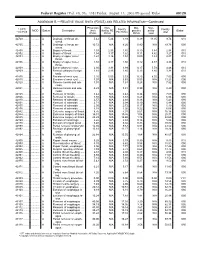

RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) and RELATED INFORMATION—Continued

Federal Register / Vol. 68, No. 158 / Friday, August 15, 2003 / Proposed Rules 49129 ADDENDUM B.—RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) AND RELATED INFORMATION—Continued Physician Non- Mal- Non- 1 CPT/ Facility Facility 2 MOD Status Description work facility PE practice acility Global HCPCS RVUs RVUs PE RVUs RVUs total total 42720 ....... ........... A Drainage of throat ab- 5.42 5.24 3.93 0.39 11.05 9.74 010 scess. 42725 ....... ........... A Drainage of throat ab- 10.72 N/A 8.26 0.80 N/A 19.78 090 scess. 42800 ....... ........... A Biopsy of throat ................ 1.39 2.35 1.45 0.10 3.84 2.94 010 42802 ....... ........... A Biopsy of throat ................ 1.54 3.17 1.62 0.11 4.82 3.27 010 42804 ....... ........... A Biopsy of upper nose/ 1.24 3.16 1.54 0.09 4.49 2.87 010 throat. 42806 ....... ........... A Biopsy of upper nose/ 1.58 3.17 1.66 0.12 4.87 3.36 010 throat. 42808 ....... ........... A Excise pharynx lesion ...... 2.30 3.31 1.99 0.17 5.78 4.46 010 42809 ....... ........... A Remove pharynx foreign 1.81 2.46 1.40 0.13 4.40 3.34 010 body. 42810 ....... ........... A Excision of neck cyst ........ 3.25 5.05 3.53 0.25 8.55 7.03 090 42815 ....... ........... A Excision of neck cyst ........ 7.07 N/A 5.63 0.53 N/A 13.23 090 42820 ....... ........... A Remove tonsils and ade- 3.91 N/A 3.63 0.28 N/A 7.82 090 noids. -

Anal Fistula

ANAL FISTULA This leaflet is produced by the Department of Colorectal Surgery at Beaumont Hospital supported by an unrestricted grant to better Beaumont from the Beaumont Hospital Cancer Research and Development Trust. This information leaflet has been designed to give you general guidelines and advice regarding your surgery. Not all of this information may be relevant to your circumstances. Please discuss any queries with your doctor or nurse. YOUR TREATMENT EXPLAINED What is a fistula? A fistula is a small tract or tunnel between the back passage and the external skin on the buttocks. This is usually the result of a previous abscess which has drained but which has not fully healed. This results in an intermittent or persistent discharge or leaking of pus or blood. Once a tract has been formed it will remain in place as long as there is pus draining through it. There are different types of fistula. Some develop as a single tract from your rectum (back passage) through to the external skin (simple fistula). Others may branch of into different directions creating more than one tract (complex fistula). How can a fistula be treated? Treatment for a fistula varies from person to person depending on the type of fistula and how each individual fistula responds following surgery. Most of these procedures are carried out as a day case procedure. You will come to the Day ward on the morning of your procedure. You will usually be able to go home the same day once you have recovered from your anaesthetic. The aim of treating a fistula is to drain away any pus allowing inflammation to settle and ultimately the tract to heal. -

Funding Research to Fight Diseases of the Gut, Liver & Pancreas

FUNDING RESEARCH TO FIGHT DISEASES OF THE GUT, LIVER & PANCREAS THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM THIS FACTSHEET IS ABOUT ANAL FISTULAS An anal fistula is a channel that develops between the end of the bowel and the skin near the anus. CAUSES WHAT IS THE CAUSE OF ANAL FISTULAS? Anal fistulas are normally caused by an infection around the anus. The infection causes a build-up of pus (abscess) that leaves a channel behind when it has drained away. The channel (fistula) persists causing symptoms of pain and irritation, smelly discharge from near the anus that can look like pus or blood, and painful swellings (abscesses). The end of the fistula may be visible as a hole or small lump in the skin close to the anus. More rarely a fistula develops due to other medical conditions such as Crohn’s disease (a type of inflammatory bowel disease), hidradenitis suppurativa (a skin condition), infection with tuberculosis (TB) or HIV, or following radiotherapy or chemotherapy cancer treatment. A fistula is a channel (or sinus) between the end of the bowel (anus or rectum) and the skin near the anus (as in this image.) DIAGNOSIS HOW ARE FISTULAS DIAGNOSED? Your doctor will examine you and ask about your symptoms. Some fistulas can be easy to see but others might need to be identified by using an MRI or specialist ultrasound scan to see where the tract is. HOW CAN ANAL FISTULAS AFFECT YOU? An anal infection or abscess is quite common and does not always lead to a fistula. Fistulas may result in pain, itching and a smelly discharge. -

Discharge Instructions After Fistulotomy

FAIRFAX COLON & RECTAL SURGERY, P.C. DONALD B. COLVIN, M.D., F.A.S.C.R.S. PAUL E. SAVOCA, M.D., F.A.S.C.R.S. LYNDA S. DOUGHERTY, M.D., F.A.S.C.R.S. DANIEL P. OTCHY, M.D., F.A.S.C.R.S. LAWRENCE E. STERN, M.D., F.A.S.C.R.S. KIMBERLY A. MATZIE, M.D., F.A.C.S. COLORECTAL/ANORECTAL SURGERY, COLONOSCOPY, ANORECTAL PHYSIOLOGY (703) 280-2841 DISCHARGE INSTRUCTIONS AFTER FISTULOTOMY An anal fistula is an abnormal channel or tunnel-like chronic infection that starts inside the anus and ends outside on the skin around the anus. Its development is usually the result of a previous anal infection or abscess. About 50% of people with an anal abscess end up with a fistula. Most fistulas are short and superficial and are best treated by simply opening the entire tunnel and leaving it open to heal in gradually. Occasionally a patient can have a complex fistula with multiple tracts or the tunnel may traverse a considerable amount of the sphincter muscle. For this reason the surgical treatment has to be individualized for each particular patient depending on the location and anatomy of the fistula. Frequently, the surgeon cannot guarantee exactly what will need to be done until the examination that is done under anesthesia at the time of the surgery. It is important to realize that the operative procedure can change depending on what is found at the time of the surgery. At times a fistula will require more than one surgery to cure. -

Diagnostic Codes

DISEASES OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM DISEASES OF ORAL CAVITY, SALIVARY GLANDS AND JAWS (520 - 529.9) 520 DISORDERS OF TOOTH DEVELOPMENT AND ERUPTION 520.0 ANODONTIA 520.1 SUPERNUMERARY TEETH 520.2 ABNORMALITIES OF SIZE AND FORM 520.3 MOTTLED TEETH 520.4 DISTURBANCES OF TOOTH FORMATION 520.5 HEREDITARY DISTURBANCES IN TOOTH STRUCTURE, NOT ELSEWHERE CLASSIFIED 520.6 DISTURBANCES IN TOOTH ERUPTION 520.7 TEETHING SYNDROME 520.8 OTHER DISORDERS OF TOOTH DEVELOPMENT 520.9 UNSPECIFIED 521 DISEASES OF HARD TISSUES OF TEETH 521.0 DENTAL CARIES 521.1 EXCESSIVE ATTRITION 521.2 ABRASION 521.3 EROSION 521.4 PATHOLOGICAL RESORPTION 521.5 HYPERCEMENTOSIS 521.6 ANKYLOSIS OF TEETH 521.7 POSTERUPTIVE COLOUR CHANGES 521.8 OTHER DISEASES OF HARD TISSUES OF TEETH 521.9 UNSPECIFIED 522 DISEASES OF PULP AND PERIAPICAL TISSUES 522.0 PULPITIS 522.1 NECROSIS OF THE PULP 522.2 PULP DEGENERATION 522.3 ABNORMAL HARD TISSUE FORMATION IN PULP 522.4 ACUTE APICAL PERIODONTITIS OF PULPAL ORIGIN 522.5 PERIAPICAL ABSCESS WITHOUT SINUS 522.6 CHRONIC APICAL PERIODONTITIS 522.7 PERIAPICAL ABSCESS WITH SINUS 522.8 RADICULAR CYST 522.9 OTHER AND UNSPECIFIED 523 GINGIVAL AND PERIODONTAL DISEASES 523.0 ACUTE GINGIVITIS 523.1 CHRONIC GINGIVITIS 523.2 GINGIVAL RECESSION 523.3 ACUTE PERIODONTITIS 523.4 CHRONIC PERIODONTITIS 523.5 PERIODONTOSIS 523.6 ACCRETIONS ON TEETH 523.8 OTHER PERIODONTAL DISEASES 523.9 UNSPECIFIED 524 DENTOFACIAL ANOMALIES, INCLUDING MALOCCLUSION 524.0 MAJOR ANOMALIES OF JAW SIZE 524.1 ANOMALIES OF RELATIONSHIP OF JAW TO CRANIAL BASE 524.2 ANOMALIES OF DENTAL ARCH -

Fistula in Ano

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC MD Theses Special Collections 5-1-1935 Fistula in ano Julius B. Christensen University of Nebraska Medical Center This manuscript is historical in nature and may not reflect current medical research and practice. Search PubMed for current research. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses Part of the Medical Education Commons Recommended Citation Christensen, Julius B., "Fistula in ano" (1935). MD Theses. 375. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses/375 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in MD Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FISTULA .- IN AJ'iO Senior Thesis - Omaha, Nebraska April 1935 Julius B. Christensen - B. So. in Med. Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Nebraska College of Medicine in partial fullfillment of the requirements for Degree of Doctor of Medicine. 480680 C01TTENTS History Page 1 Anatomy tt 6 Origin It 13 Etiology • 18 It ?"--, Cla.ssii'ication 23 Symptomatology It 25 Diagnosis .. 26 Treatment '* 28 Prognosis It 34 SU!.!lll1ary .. 36 Bibliography " -- Page 1 HISTORY The term qfistula,· from the Latin word meaning a reed or pipe was probably applied to the condition because of the existence of the tube-like channel through which gas of feces escape in a complete fistula. A complete fistula may be defined as an unhealthy or non-granulating sinus with two openings, one on the surface, usually near the anus, and the other in the rectum.