Yosemite: Where to Go and What Go Do (1888) by George G. Mackenzie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sketch of Yosemite National Park and an Account of the Origin of the Yosemite and Hetch Hetchy Valleys

SKETCH OF YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK AND AN ACCOUNT OF THE ORIGIN OF THE YOSEMITE AND HETCH HETCHY VALLEYS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY 1912 This publication may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington. I). C, for LO cents. 2 SKETCH OP YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK AND ACCOUNT OF THE ORIGIN OF THE YOSEMITE AND HETCH HETCHY VALLEYS. By F. E. MATTHES, U. S. Geological Surrey. INTRODUCTION. Many people believe that the Yosemite National Park consists principally of the Yosemite Valley and its bordering heights. The name of the park, indeed, would seem to justify that belief, yet noth ing could be further from the truth. The Yosemite Valley, though by far the grandest feature of the region, occupies only a small part of the tract. The famous valley measures but a scant 7 miles in length; the park, on the other hand, comprises no less than 1,124 square miles, an area slightly larger than the State of Rhode Island, or about one-fourth as large as Connecticut. Within this area lie scores of lofty peaks and noble mountains, as well as many beautiful valleys and profound canyons; among others, the Iletch Hetchy Valley and the Tuolumne Canyon, each scarcely less wonderful than the Yosemite Valley itself. Here also are foaming rivers and cool, swift trout brooks; countless emerald lakes that reflect the granite peaks about them; and vast stretches of stately forest, in which many of the famous giant trees of California still survive. The Yosemite National Park lies near the crest of the great alpine range of California, the Sierra Nevada. -

Yosemite Valley

SELF-GUIDING AUTOqJ TOUR. YOSEMITE VALLEY Tunnel View Special Number YOSEMITE NATURE NOTES January, 1942 Yosemite Nature Notes THE MONTHLY PUBLICATION OF THE YOSEMITE NATURALIST DEPARTMENT AND THE YOSEMITE NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION VOL. lIXI IANUARY, 1942 NO. I SELF-GUIDING AUTO TOUR OF YOSEMITE VALLEY M. E. Beatty and C. A. Harwell This sell-guiding auto tour has GOVERNMENT CENTER been arranged for the visitor who TO INDIAN CAVES ants to discover and visit the scen- ic and historic points of interest in 12.0 miles) Yosemite Valley . It is a complete circle tour of the valley floor, a total Government Center, our starting distance of around 22 miles, and will point, is made up of the Yosemite require at least two hours. Museum, National Park Service Ad- We will first visit the upper or ministration Building, Post Office, eastern end of Yosemite Valley. photographic and art studios and Principal stopping points will be In- the Rangers Club . The Museum dims Caves, Mirror Lake, Happy is a key to the park . We will do well Isles, Stoneman Meadow, Camp to spend some time studying its well Curry and the Old Village . planned exhibits before our trip to 2 YOSEMITE NATURE NOTES learn what to look for; and again at a cost of over a million dollars. Its the close of our tour to review and architecture is of rare beauty. fix what we have learned and to Leaving the hotel grounds we have questions answered that have torn arisen south along the open meadow to the . next intersection where we turn left. -

Yosemite, Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks 5

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Yosemite, Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks Yosemite National Park p44 Around Yosemite National Park p134 Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks p165 Michael Grosberg, Jade Bremner PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Yosemite, YOSEMITE NATIONAL Tuolumne Meadows . 80 Sequoia & PARK . 44 Hetch Hetchy . 86 Kings Canyon . 4 Driving . 87 Yosemite, Sequoia & Day Hikes . 48 Kings Canyon Map . 6 Yosemite Valley . 48 Cycling . 87 Yosemite, Sequoia & Big Oak Flat Road Other Activities . 90 Kings Canyon Top 16 . 8 & Tioga Road . 56 Winter Activities . 95 Need to Know . 16 Glacier Point & Sights . 97 Badger Pass . 60 What’s New . 18 Yosemite Valley . 97 Tuolumne Meadows . 64 If You Like . 19 Glacier Point & Wawona . 68 Month by Month . 22 Badger Pass Region . 103 Hetch Hetchy . 70 Itineraries . 24 Tuolumne Meadows . 106 Activities . 28 Overnight Hikes . 72 Wawona . 109 Yosemite Valley . 74 Travel with Children . 36 Along Tioga Road . 112 Big Oak Flat & Travel with Pets . 41 Big Oak Flat Road . 114 Tioga Road . 75 Hetch Hetchy . 115 Glacier Point & Badger Pass . 78 Sleeping . 116 Yosemite Valley . 116 VEZZANI PHOTOGRAPHY/SHUTTERSTOCK © VEZZANI PHOTOGRAPHY/SHUTTERSTOCK DECEMBER35/SHUTTERSTOCK © NIGHT SKY, GLACIER POINT P104 PEGGY SELLS/SHUTTERSTOCK © SELLS/SHUTTERSTOCK PEGGY HORSETAIL FALL P103 VIEW FROM TUNNEL VIEW P45 Contents UNDERSTAND Yosemite, Sequoia & TAHA RAJA/500PX TAHA Kings Canyon Today . .. 208 History . 210 Geology . 216 © Wildlife . 221 Conservation . 228 SURVIVAL GUIDE VIEW OF HALF DOME FROM Clothing & GLACIER POINT P104 Equipment . 232 Directory A–Z . 236 Glacier Point & SEQUOIA & KINGS Badger Pass . 118 Transportation . 244 CANYON NATIONAL Health & Safety . 249 Big Oak Flat Road & PARKS . -

Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Rock Falls in Yosemite Valley, California by Gerald F. Wieczorek1, James B. Sn

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY ROCK FALLS IN YOSEMITE VALLEY, CALIFORNIA BY GERALD F. WIECZOREK1, JAMES B. SNYDER2, CHRISTOPHER S. ALGER3, AND KATHLEEN A. ISAACSON4 Open-File Report 92-387 This work was done with the cooperation and assistance of the National Park Service, Yosemite National Park, California. This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards (or with the North American Stratigraphic Code). Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government 'USGS, Reston, VA 22092, 2NPS, Yosemite National Park, CA, 95389, 3McLaren/Hart, Alameda, CA 94501, 4Levine Fricke, Inc., Emeryville, CA 94608 Reston, Virginia December 31, 1992 CONTENTS Page Abstract ............................................... 1 Introduction .............................................. 1 Geologic History ........................................... 2 Methods of Investigation ..................................... 5 Inventory of historical slope movements ........................ 5 Location ............................................ 5 Time of occurrence .......:............................ 7 Size ............................................... 8 Triggering mechanisms ................................. 9 Types of slope movement ................................ 11 Debris flows ...................................... 11 Debris slides ...................................... 12 Rock slides ...................................... -

Figure 2.5-1

) ) # ) # k e e r Basket Dome C l i n ) Lehamite Falls a o ) # r ) y T R n i k a b f e k a b C e u e o k r e n x n e r a C e S C i C r e n r d o w e C n m w e t o I e i o k h C n c m S r D r e Arrowhead Spire e s A h e k o l t r Y a # o ) y Upper Yosemite Fall ) o ) N North Dome ##Yosemite Point R Eagle Tower Lost Arrow Castle Cliffs # k # ree C # ya na Yosemite Village Te Lower Yosemite Fall Historic District ) oop ) ke L ) r La ro Yosemite Village Ahwahnee Hotel ir Historic Landmark Royal Arch Cascade M ) ) ) # k Ahwahn Washington Column e e e e e Columbia Point v R r o Rangers' Club i ad # r C Eagle Peak il ^_ e a D Royal Arches l # Tr Historic Landmark Ahwahnee g p e g a # o o a Meadow # E L l l N y i or le Cook's thsi Valley l V de Sugar Pine Bridge L Va Meadow D oop # Yosemite Lodge r Backpackers Tra ad iv B IB il e ro B e I Lak E Three Brothers Middle Brother IB I Campground r l Ahwahnee o r C Housekeeping Sentinel Bridge ir a # Bridge # Camp 4 Camp North Pines Lamon M Diving Board p Yosemite Valley B i Wahhoga Indian I t Stoneman Historic District B # a I Tenaya Bridge n Cultural Center Chapel ^_ Meadow T LeConte Memorial Lodge IB Lower Pines r a ^ Historic Landmark ^_ Stoneman Bridge i Substation Sentinel l IB Ribbon Fall (removed) Meadow Clarks Bridge ) Leidig Curry Village ) Lower Brother ) K P Pinnacle IB # Meadow Moran Point k # e e # El Capitan v e i r r ) D Union Point ) C # ) e Upper Pines e # c d i # Camp Curry Village s a Split Pinnacle Staircase Falls l h p t Historic District e r r i o F # N IB Happy Isles Bridge # -

Osemite Uide

See Yosemite Today YOSEMITE for a complete calendar of GUIDE what’s happening Your Key to Visiting the Park in the park. WINTER/SPRING 2001-2002 25¢ VOLUME XXXI, NO. 1 Seasons of Magic NPS Photo by C. W. Brown Look Cottonwood trees and Upper Yosemite Fall from Cook’s Meadow. Inside! very year, visitors and friends ask the same Valley Map . Back Panel question: When is the best time to visit Park Map Yosemite? For me, that’s easy—winter or Planning Your Visit. 4 & 5 spring. Just when the crowds of summer Eand fall become a memory, just when the Merced The Changing Seasons. 2 Camping . 3 River slows to a crawl, just when I think I’ve forgot- ten what rain sounds like, winter happens. Then Backpacking & Valley Day Hikes . 6 spring. And if you are fortunate enough to visit General Information . 7 Yosemite during these times of the year, it’s when magic happens as well! Continued on page 1 YOSEMITE GUIDE Your Key to Visiting the Park WINTER/SPRING 2001-2002 VOLUME XXXI, NO.1 Seasons of Magic Continued from front cover If I were to narrow it down even fur- MIRROR LAKE & HOT CHOCOLATE SPRING: ther, I would have to say that some of my Take a shuttle bus to The Ahwahnee LUNAR RAINBOW favorite seasons occur on the cusp—as fall and hike or ski out along the paved trails Can you really see a rain- fades to winter or winter explodes into just behind the hotel. (If it’s snowy, try bow at night? During the spring. -

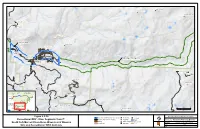

River Segments 5 and 7

Mount Bruce Buena Vista Peak # # Moraine Mountain B # i sho p C ree k T ra i l Bishop Creek ¡n Trailhead Road a n Alder Creek o w ¡n Trailhead a W a ualn Fal n ls T il rail h C k e e r C Segment 7: Wawona a ln A a ld u Wawona Dome e n r l i # C C h re Chilnualna Falls e k Trailhead T rail ¡n Wawona k e e Campground r C F h orest Drive s u Alder Creek R Trailhead Segment 5: South Fork ¡n Merced River above Wawona IB IB IB Wawona Covered Bridge ¡nWawona Point Wawona Golf Course IG Trailhead W a w on il a M ra e T ado k w e lo e op r t C Quartz Mountain rai l n ¡n o Trailhead r oad I Sk R y R anch Wawona Point # ad Ro chill ain w a Mou nt Quartz Mountain o h # C Mount Savage F # o u r M d Mount Raymond i le Roa # 2. Yosemite 1. Merced River 3. Merced Valley Above Nevada Fall Gorge Mariposa Grove osa Grove Road ¡n Trailhead 4.El Portal rip Ma Si er 5. South Fork ra N Merced River F road above Wawona 8. South Fork Map Area Merced River below Wawona Goat Meadow Snow Play Mountain UV41 # 6,7. Wawona and 0 0.5 1 Wawona ImHpougnadnm eMntountainWamelo Rock ## White Chief Mountain Recreational Corridor Scenic Corridor Wild Corridor # Miles # Figure 2.2-10 National Park Service U.S. -

MILEAGE TABLE Time Shown in Minutes; Distance Shown in Miles Hwy

MILEAGE TABLE Time shown in minutes; distance shown in miles Hwy. 140 West from Mariposa (Hwy. 49 South & Hwy. 140) Time Time (total) Distance (total) Yaqui Gulch Rd. 5 5 4 Mt. Bullion Cutoff Rd. 4 9 7.2 Hornitos Rd. 6 15 11.7 Old Highway 3 18 14.2 Chase Ranch 6 24 18.8 Merced County line 4 28 21.2 Cunningham Rd. 1 29 22.2 Planada (at Plainsburg Rd.) 5 34 28.8 Merced and Highway 99 11 45 37.4 Hwy. 140 East from Mariposa (Hwy. 49 South & Hwy. 140) Time Time (total) Distance (total) Hwy. 49 North & Hwy.140 (four way stop) 2 2 0.9 E Whitlock Rd. 4 6 4.1 Triangle Rd. 2 8 5.1 Carstens Rd. 2 10 7.2 Colorado Rd. 2 12 8.6 Yosemite Bug 2 14 10 Briceburg 4 18 12.7 Ferguson Slide 10 28 20.8 South Fork Merced River* 2 30 21.9 Indian Flat Campground* 5 35 24.5 Foresta Rd. at bridge* 5 40 26.8 Foresta Rd. at 'old' El Portal* 2 42 28 YNP Arch Rock Entrance* 6 48 31.5 Big Oak Flat Rd.* 9 57 36.5 Wawona Rd.* 2 59 37.4 Hwy. 49 South from Mariposa (Hwy. 49 South & Hwy. 140) Time Time (total) Distance (total) County Fairgrounds 2 2 1.7 Silva Rd. / Indian Peak Rd. 3 5 4.5 Darrah Rd. 1 6 5.3 Woodland Rd. and Hirsch Rd. 3 9 7.7 Usona Rd. and Tip Top Rd. 2 11 9.6 Triangle Rd. -

Yosemite National Park

COMPLIMENTARY $3.95 2019/2020 YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE PARKS YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK ACTIVITIES • SIGHTSEEING • DINING • LODGING TRAILS • HISTORY • MAPS • MORE OFFICIAL PARTNERS T:5.375” S:4.75” WELCOME S:7.375” SO TASTY EVERYONE WILL WANT A BITE. WelcomeT:8.375” to Yosemite National Park. There are as many ways to experience this FUN FACTS amazing place as there are granite rocks Established: Yosemite was designated as in the Sierra Nevada landscape. To make a forest reserve in 1864 by President Lin- the most of your time here, we invite you coln, Yosemite has grown into an American to peruse and be inspired by this edition of icon of wilderness. From the 3,000-foot-tall the American Park Network guide to Yosem- El Capitan to the magnificent Half Dome, ite National Park. We hope you find it use- Yosemite’s beauty is unrivaled. The park ful during your visit to the area. became a World Heritage Site in 1984 and This guide represents the collaborative attracts a vast number of visitors. efforts of the American Park Network and a Land Area: Yosemite is 761,787 acres and number of park partners—organizations is known for its waterfalls, giant granite dedicated both to Yosemite and to making cliffs and stunning sequoias. your stay enjoyable and memorable. We Highest Elevation: The peak of Mt. Lyell are grateful to the legions of staff and vol- at 13,114 feet. unteers who work together to ensure that the wonders of this park are preserved. Plants & Animals: In total, Yosemite is (See the “Who’s Who at the Park” chap- home to more than 400 species of verte- brates. -

Wild WSR Corridor Figure 2.3-3 Ansel Adams Wilderness Yosemite

# S n o w C # r e e k ek re C r i s ne u # S # Half D#ome Jo Merced Lake Diving Board hn Muir Trail # #Moraine Dome High Sierra Camp Mount Maclure Bunnell Point # Merced Lake # Lost Lake # Ranger Station Mount Florence ek Little Yosemite Valley Merced Lake # Mount Lyell Mount Broderick re !@ C # # st o pn L # Liberty Cap # # Logjam #Cascade Cliffs # # k Starr King Lake r o F k Quartzite Peak a e # P Washburn y a Lake r G r Mount Starr King e L v y i ell Fo k M # R r e r d c e e c d Electra Peak r Yosemite Wilderness e R # iv M e k r r o Mount Clark F k a # e T Mount Ansel Adams P ri d pl # e e R Pe ak FMo kr e r c e d Foerster Peak R # i v k e e r re F ore C s rt Cr Gr a y e eek r e v i R d Gray Peak e c # r e M Harriet k r o Lake F k a k e Long Mountain Cree ed P R rc e # ed M Ansel Adams Red Peak# Wilderness #Isberg Peak 2. Yosemite 1. Merced River 3. Merced Valley Above Nevada Fall Gorge 4.El Portal Edna Ottoway Peak L O y Lake ong Creek tto wa Cr # eek Merced Peak Sadler Peak 5. South Fork Map Area d 8. South Fork e # Merced River h # Merced River s above Wawona r ed River Watershed below Wawona e rc t e a Triple Divide Peak M 6,7. -

Frommer's Yosemite & Sequoia/Kings Canyon National Parks 4Th

00 542869 FM.qxd 1/21/04 8:54 AM Page i Yosemite & Sequoia/Kings Canyon National Parks 4th Edition by Don & Barbara Laine & Eric Peterson Here’s what critics say about Frommer’s: “Amazingly easy to use. Very portable, very complete.” —Booklist “Detailed, accurate, and easy-to-read information for all price ranges.” —Glamour Magazine 00 542869 FM.qxd 1/21/04 8:54 AM Page ii Published by: WILEY PUBLISHING,INC. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5744 Copyright © 2004 Wiley Publishing, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as per- mitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978/750-8400, fax 978/646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permis- sion should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317/572-3447, fax 317/572-4447, E-Mail: [email protected]. Wiley and the Wiley Publishing logo are trademarks or registered trade- marks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates. Frommer’s is a trademark or registered trademark of Arthur Frommer. Used under license. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Wiley Publishing, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. -

Yosemite Wilderness Figure 2.4-1A Ansel

# # # 2. Yosemite 1. Merced River 3. Merced Valley Above Nevada Fall Gorge 4.El Portal Rodgers Peak 5. South Fork # Merced River Map Area 8. South Fork above Wawona Merced River k below Wawona r Quartzite Peak o F k Washburn # a 6,7. Wawona and e P Wawona Impoundment Lake y a Recreational Corridor Scenic Corridor Wild Corridor r G # Lye ll Fork Merced R iv e r Electra Peak Yosemite Wilderness # Mount Clark r e v # i Mount Ansel Adams R T r ip d l # e e P c e r ak e Fo M rk k M r e o r c F e k a d e R Foerster Peak P ed i R v e # r k F e ore re ster C Gra y C reek r e v i Gray Peak R d # e rc e Harriet M k Lake r o F k a e P eek d Long Mountain Cr e Ansel Adams ed c R r # e M Wilderness Red Peak # Isberg Peak # N o r t h F o r k S a n Jo a q Edna u Ottoway Peak i O Lake Lo n Cr ng reek R t towa y ee # s C k s i a v e P r g r e b Trip Fork Mer s le Peak ced I Ri Sadler Peak Merced Peak ver # # 0 0.5 1 e n o n Triple Divide Peak # Miles # National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Figure 2.4-1a Wild WSR Corridor Classification Trail Ê Produced by: Yosemite Planning Division Scenic ORV - River Segment 1.