Markie Williams As a 12-Year-Old, Painted by Her Father, Captain William G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mrs. General Lee's Attempts to Regain Her Possessions After the Cnil War

MRS. GENERAL LEE'S ATTEMPTS TO REGAIN HER POSSESSIONS AFTER THE CNIL WAR By RUTH PRESTON ROSE When Mary Custis Lee, the wife of Robert E. Lee, left Arlington House in May of 1861, she removed only a few of her more valuable possessions, not knowing that she would never return to live in the house which had been home to her since her birth in 1808. The Federal Army moved onto Mrs. Lee's Arling ton estate on May 25, 1861. The house was used as army headquarters during part of the war and the grounds immediately around the house became a nation al cemetery in 1864. Because of strong anti-confederate sentiment after the war, there was no possibility of Mrs. Lee's regaining possession of her home. Restora tion of the furnishings of the house was complicated by the fact that some articles had been sent to the Patent Office where they were placed on display. Mary Anna Randolph Custis was the only surviving child of George Washing ton Parke Custis and Mary Lee Fitzhugh. Her father was the grandson of Martha Custis Washington and had been adopted by George Washington when his father, John Custis, died during the Revolutionary War. The child was brought up during the glorious days of the new republic, living with his adopted father in New York and Philadelphia during the first President's years in office and remaining with the Washingtons during their last years at Mount Vernon. In 1802, after the death of Martha Washington, young Custis started building Arlington House on a hill overlooking the new city of Washington. -

Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through His Life at Arlington House

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Fall 2020 The House That Built Lee: Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House Cecilia Paquette University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Paquette, Cecilia, "The House That Built Lee: Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House" (2020). Master's Theses and Capstones. 1393. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/1393 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOUSE THAT BUILT LEE Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House BY CECILIA PAQUETTE BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2017 BFA, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, 2014 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History September, 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 2020 Cecilia Paquette ii This thesis was examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in History by: Thesis Director, Jason Sokol, Associate Professor, History Jessica Lepler, Associate Professor, History Kimberly Alexander, Lecturer, History On August 14, 2020 Approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. !iii to Joseph, for being my home !iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisory committee at the University of New Hampshire. -

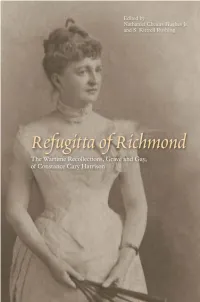

The Wartime Recollections, Grave and Gay, of Constance Cary Harrison / Edited, Annotated, and with an Introduction by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr

Refugitta of Richmond RefugittaThe Wartime Recollections, of Richmond Grave and Gay, of Constance Cary Harrison Edited by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and S. Kittrell Rushing The University of Tennessee Press • Knoxville a Copyright © 2011 by The University of Tennessee Press / Knoxville. All Rights Reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. First Edition. Originally published by Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1916. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843–1920. Refugitta of Richmond: the wartime recollections, grave and gay, of Constance Cary Harrison / edited, annotated, and with an introduction by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and S. Kittrell Rushing. — 1st ed. p. cm. Originally published under title: Recollections grave and gay. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911. Includes bibliographical references and index. eISBN-13: 978-1-57233-792-3 eISBN-10: 1-57233-792-3 1. Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843–1920. 2. United States—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Personal narratives, Confederate. 3. Virginia—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Personal narratives, Confederate. 4. United States—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Women. 5. Virginia—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Women. 6. Richmond (Va.)—History—Civil War, 1861–1865. I. Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs. II. Rushing, S. Kittrell. III. Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843-1920 Recollections grave and gay. IV. Title. E487.H312 2011 973.7'82—dc22 20100300 Contents Preface ............................................. ix Acknowledgments .....................................xiii -

Documenting Women's Lives

Documenting Women’s Lives A Users Guide to Manuscripts at the Virginia Historical Society A Acree, Sallie Ann, Scrapbook, 1868–1885. 1 volume. Mss5:7Ac764:1. Sallie Anne Acree (1837–1873) kept this scrapbook while living at Forest Home in Bedford County; it contains newspaper clippings on religion, female decorum, poetry, and a few Civil War stories. Adams Family Papers, 1672–1792. 222 items. Mss1Ad198a. Microfilm reel C321. This collection of consists primarily of correspondence, 1762–1788, of Thomas Adams (1730–1788), a merchant in Richmond, Va., and London, Eng., who served in the U.S. Continental Congress during the American Revolution and later settled in Augusta County. Letters chiefly concern politics and mercantile affairs, including one, 1788, from Martha Miller of Rockbridge County discussing horses and the payment Adams's debt to her (section 6). Additional information on the debt appears in a letter, 1787, from Miller to Adams (Mss2M6163a1). There is also an undated letter from the wife of Adams's brother, Elizabeth (Griffin) Adams (1736–1800) of Richmond, regarding Thomas Adams's marriage to the widow Elizabeth (Fauntleroy) Turner Cocke (1736–1792) of Bremo in Henrico County (section 6). Papers of Elizabeth Cocke Adams, include a letter, 1791, to her son, William Cocke (1758–1835), about finances; a personal account, 1789– 1790, with her husband's executor, Thomas Massie; and inventories, 1792, of her estate in Amherst and Cumberland counties (section 11). Other legal and economic papers that feature women appear scattered throughout the collection; they include the wills, 1743 and 1744, of Sarah (Adams) Atkinson of London (section 3) and Ann Adams of Westham, Eng. -

Reconstructing the Self and the American: Civil War Veterans in Khedival Egypt

TARIK TANSU YİĞİT RECONSTRUCTING THE SELF AND THE AMERICAN: CIVIL WAR VETERANS IN KHEDIVAL EGYPT RECONSTRUCTING THE SELF AND THE CIVIL WAR VETERANS IN KHEDIVAL EGYPT A Ph.D. Dissertation by TARIK TANSU YİĞİT AMERICAN : Bilkent University Bilkent Department of History İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University Ankara August 2020 20 20 To my grandmother/babaanneme. RECONSTRUCTING THE SELF AND THE AMERICAN: CIVIL WAR VETERANS IN KHEDIVAL EGYPT The Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by TARIK TANSU YİĞİT In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA August 2020 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. ----------------------------- Asst. Prof. Dr. Kenneth Weisbrode Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. ----------------------------- Prof. Dr. Tanfer Emin Tunç Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. ----------------------------- Asst. Prof. Dr. Owen Miller Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -

Lee Family Member Faqs

HOME ABOUT FAMILY PAPERS REFERENCES RESOURCES PRESS ROOM Lee Family Member FAQs Richard Lee, the Immigrant The Lee Family Digital Archive is the largest online source for Who was RL? primary source materials concerning the Lee family of Richard Lee was the ancestor of the Lee Family of Virginia, many of whom played prominent roles in the Virginia. It contains published political and military affairs of the colony and state. Known as Richard Lee the Immigrant, his ancestry is not and unpublished items, some known with certainty. Since he became one of Virginia's most prominent tobacco growers and traders he well known to historians, probably was a younger son of a substantial family involved in the mercantile and commercial affairs of others that are rare or have England. Coming to the New World, he could exploit his connections and capital in ways that would have been never before been put online. impossible back in England. We are always looking for new When was RL Born? letters, diaries, and books to add to our website. Do you Richard Lee was born about 1613. have a rare item that you Where was RL Born? would like to donate or share with us? If so, please contact Richard Lee was born in England, but no on knows for sure exactly where. Some think his ancestors came our editor, Colin Woodward, at from Shropshire while others think Worcester. (Indeed, a close friend of Richard Lee said Lee's family lived in (804) 493-1940, about how Shropshire, as did a descendent in the eighteenth century.) Attempts to tie his ancestry to one of the dozen or you can contribute to this so Lee familes in England (spelled variously as Lee, Lea, Leight, or Lega) that appeared around the time of the historic project. -

Foundation Document Overview, Arlington

Description NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR In 1831 Mary Anna Randolph Custis, the Selina Gray’s daughter of George Washington Parke Custis, quarters married Robert E. Lee, a young U.S. Army Summer Kitchen/ George Clark’s officer from another prominent Virginia family. Black History Foundation Document Overview quarters Exhibit Arlington House became the family’s primary residency and they lived on the estate for 30 North Wing Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial Store Entrance Room Bath and years, raising seven children. Arlington House Hunting Water Closet Virginia Hall Outer Hall functioned as a working plantation and consisted Conservatory Dining Pantry of owners, both the Custis and Lee families, and Center Room White Hall Inner Hall Parlor slaves, which numbered as many as 63 at one time. Morning Family Guest Room Parlor Chamber The Lee family lived at the estate until Robert E. School and Sewing Room Lee’s resignation from the U.S. Army in 1861. Office Entrance Mr. and Mrs. and Custis’ Chamber Studio PORTICO Robert E. Lee’s decision to resign from the U.S. Army and serve his native state of Virginia in the Confederacy would forever change Arlington Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, was formally House and profoundly impacted the course of the Civil War. designated by the federal government on June 29, 1955, Following his resignation, the Lee family left Arlington and through Public Law 84-107 to suitably memorialize Robert Union forces occupied this strategic location on the Virginia E. Lee. Robert E. Lee lived at Arlington House for 30 years side of the Potomac River. -

Arlington House U.S

National Park Service Arlington House U.S. Department of the Interior The Robert E. Lee Memorial The Spectacle New Museum Technician for Arlington House Laura Anderson has been selected as the new Museum Technician for Arlington House. She starts work on Tuesday, February 22nd. Her schedule is Sunday through Thursday, 6:30-3:00. Laura comes to us from the Little Compton, Rhode Island Historical Society, specifically the Wilbor House (http://users.ids.net/~ricon/lchs/), where she has been the sole paid employee for the past couple of years. Her experience is vast and varied - she does all the historic housekeeping, environmental monitoring and pest control as well as trains the volunteers, gives school programs and standard tours, researches and writes articles, writes and publishes the newsletter, and plans and executes short term exhibits. Laura is from the Midwest, was educated in Camera crew was on site for inauguration, January 20, 2005. San Francisco (History degrees) and then came to the East Coast to work and study, recently receiving her certificate in Museum Studies from Harvard Extension. She History Happenings volunteered for the NPS at the Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor This month marks the debut of a new feature Arlington House restored? Hints: 1. She was working on projects from river clean up to in The Spectacle. Many of you have asked for the wife of a senator from New Hampshire 2. cataloguing artifacts. a regular update on the history of the house, She served as an editor at Good Housekeeping current research findings, work projects, etc. -

![Arlington House Historic District [2013 Boundary Increase & Additional Documentation] Other Names/Site Number: Arlington House, the Robert E](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3176/arlington-house-historic-district-2013-boundary-increase-additional-documentation-other-names-site-number-arlington-house-the-robert-e-6013176.webp)

Arlington House Historic District [2013 Boundary Increase & Additional Documentation] Other Names/Site Number: Arlington House, the Robert E

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Arlington House Historic District [2013 Boundary Increase & Additional Documentation] Other names/site number: Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial (National Park); Mount Washington; Custis-Lee Mansion; Lee Mansion; Arlington National Cemetery Headquarters (VDHR# 000-0001; 44AR0017; 44AR0032) Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _Roughly bounded by Sheridan Dr., Ord & Weitzel Dr., Humphreys Drive & Lee Avenue in Arlington National Cemetery City or town: Arlington State: VA County: Arlington Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Download a PDF Version of the Guide to African American Manuscripts

Guide to African American Manuscripts In the Collection of the Virginia Historical Society A [Abner, C?], letter, 1859. 1 p. Mss2Ab722a1. Written at Charleston, S.C., to E. Kingsland, this letter of 18 November 1859 describes a visit to the slave pens in Richmond. The traveler had stopped there on the way to Charleston from Washington, D.C. He describes in particular the treatment of young African American girls at the slave pen. Accomack County, commissioner of revenue, personal property tax book, ca. 1840. 42 pp. Mss4AC2753a1. Contains a list of residents’ taxable property, including slaves by age groups, horses, cattle, clocks, watches, carriages, buggies, and gigs. Free African Americans are listed separately, and notes about age and occupation sometimes accompany the names. Adams family papers, 1698–1792. 222 items. Mss1Ad198a. Microfilm reels C001 and C321. Primarily the papers of Thomas Adams (1730–1788), merchant of Richmond, Va., and London, Eng. Section 15 contains a letter dated 14 January 1768 from John Mercer to his son James. The writer wanted to send several slaves to James but was delayed because of poor weather conditions. Adams family papers, 1792–1862. 41 items. Mss1Ad198b. Concerns Adams and related Withers family members of the Petersburg area. Section 4 includes an account dated 23 February 1860 of John Thomas, a free African American, with Ursila Ruffin for boarding and nursing services in 1859. Also, contains an 1801 inventory and appraisal of the estate of Baldwin Pearce, including a listing of 14 male and female slaves. Albemarle Parish, Sussex County, register, 1721–1787. 1 vol. -

This Kingdom of My Childhood Landscape, Memory, and Meaning at Arlington's Flower Garden by KAREN B

This Kingdom of My Childhood Landscape, Memory, and Meaning at Arlington's Flower Garden BY KAREN B. KINZEY Is it at the touch of memory only that flowers bloom here in such exquisite perfection? Elizabeth Randolph Calvert, c.1870 On a hot Sunday in July, 1890, Mildred Childe Lee, the youngest daugh ter of the South's most famous general, sat in a pew in Grace Episcopal Church in Lexington, Virginia, far removed from the scenes of her girlhood home. A lady with "a rich, sweet voice" began to sing "Jesus Saviour of My Soul." The familiar words of the old hymn instantly transported Mildred back to the flower garden at Arlington House. "In those days of long ago ... there I used to sing that hymn and pray to be good ... and my heart did glow with a certain fervour, but whether it was hatred of sin or delight in the sweet starry blossoms I cannot tell," she recalled poignantly. 1 In linking the garden's natural beauty with spiritual associations, Mildred Lee carried on a time-honored Arlington tradition. Her ideals concerning the flower garden could be traced back to her grandmother, Mary Fitzhugh Custis. After her marriage to George Washington Parke Custis in 1804, "Molly" Custis assumed the role of mistress of the plantation at the age of sixteen. While her husband busied himself with agricultural endeavors and a variety of efforts to memorialize President Washington, Mrs. Custis devoted herself to her family, her home, and her faith. In Arlington's flower garden she found an outlet for her endeavors. -

The Spectacle

National Park Service Arlington House U.S. Department of the Interior The Robert E. Lee Memorial The Spectacle From the Office Down the Hall When Holidays Take a Holiday We are entering the eleventh month. Frost warnings are posted and the winter enclosure, our one rampart against the chill wind, is being readied for the mansion. It is dark when we enter the House to clean and gloaming when we leave. But although the trees are turning stony and spare and the grass will soon turn brown, there is, none- the-less, a genuine sense of celebration beginning to sound. In October, 1863, Lincoln said, “The year that is drawing towards its close, has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies.” And so it has. It is holiday season! Lincoln’s words opened his proclamation establishing Thanksgiving as a federal holiday. But Thanksgiving had already been around a long time. President George Custis violin played by Risa Browder at 2005 Open House Washington, G.W.P. Custis’ “father,” proclaimed November 26, 1789 to be a treats (which sounds suspiciously like and was, despite contemporary accounts of Thanksgiving Day. But his successor, Halloween today). Yet, there are very few costumes and treats, primarily a religious President Jefferson, felt it was historic references to these holidays— observance. Still there is no mention of it at unconstitutional to create a federal holiday. especially Thanksgiving mischief—at Arlington House. So Arlington was already in Federal hands Arlington House. before we got the day off. Now there are ten Christmas, however, has figured prominently federal holidays—and 40% of them fall in Halloween (and, to a lesser degree: All Saints at Arlington House over the years.