Defending President Lee; Debunking Recent Criticism by Alfred E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Robert E. Lee (1807-70) and Philanthropist George Peabody (1795-1869) at White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, July 23-Aug

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 444 917 SO 031 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty J. TITLE General Robert E. Lee (1807-70) and Philanthropist George Peabody (1795-1869) at White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, July 23-Aug. 30, 1869. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 33p. PUB TYPE Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Civil War (United States); *Donors; *Meetings; *Private Financial Support; *Public History; Recognition (Achievement); *Reconstruction Era IDENTIFIERS Biodata; Lee (Robert E); *Peabody (George) ABSTRACT This paper discusses the chance meeting at White Sulphur Springs (West Virginia) of two important public figures, Robert E. Lee and George Peabody, whose rare encounter marked a symbolic turn from Civil War bitterness toward reconciliation and the lifting power of education. The paper presents an overview of Lee's life and professional and military career followed by an overview of Peabody's life and career as a banker, an educational philanthropist, and one who endowed seven Peabody Institute libraries. Both men were in ill health when they visited the Greenbrier Hotel in the summer of 1869, but Peabody had not long to live and spent his time confined to a cottage where he received many visitors. Peabody received a resolution of praise from southern dignitaries which read, in part: "On behalf of the southern people we tender thanks to Mr. Peabody for his aid to the cause of education...and hail him benefactor." A photograph survives that shows Lee, Peabody, and William Wilson Corcoran sitting together at the Greenbrier. Reporting that Lee's own illness kept him from attending Peabody's funeral, the paper describes the impressive and prolonged international services in 1870. -

Mrs. General Lee's Attempts to Regain Her Possessions After the Cnil War

MRS. GENERAL LEE'S ATTEMPTS TO REGAIN HER POSSESSIONS AFTER THE CNIL WAR By RUTH PRESTON ROSE When Mary Custis Lee, the wife of Robert E. Lee, left Arlington House in May of 1861, she removed only a few of her more valuable possessions, not knowing that she would never return to live in the house which had been home to her since her birth in 1808. The Federal Army moved onto Mrs. Lee's Arling ton estate on May 25, 1861. The house was used as army headquarters during part of the war and the grounds immediately around the house became a nation al cemetery in 1864. Because of strong anti-confederate sentiment after the war, there was no possibility of Mrs. Lee's regaining possession of her home. Restora tion of the furnishings of the house was complicated by the fact that some articles had been sent to the Patent Office where they were placed on display. Mary Anna Randolph Custis was the only surviving child of George Washing ton Parke Custis and Mary Lee Fitzhugh. Her father was the grandson of Martha Custis Washington and had been adopted by George Washington when his father, John Custis, died during the Revolutionary War. The child was brought up during the glorious days of the new republic, living with his adopted father in New York and Philadelphia during the first President's years in office and remaining with the Washingtons during their last years at Mount Vernon. In 1802, after the death of Martha Washington, young Custis started building Arlington House on a hill overlooking the new city of Washington. -

Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through His Life at Arlington House

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Fall 2020 The House That Built Lee: Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House Cecilia Paquette University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Paquette, Cecilia, "The House That Built Lee: Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House" (2020). Master's Theses and Capstones. 1393. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/1393 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOUSE THAT BUILT LEE Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House BY CECILIA PAQUETTE BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2017 BFA, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, 2014 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History September, 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 2020 Cecilia Paquette ii This thesis was examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in History by: Thesis Director, Jason Sokol, Associate Professor, History Jessica Lepler, Associate Professor, History Kimberly Alexander, Lecturer, History On August 14, 2020 Approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. !iii to Joseph, for being my home !iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisory committee at the University of New Hampshire. -

James Russell Lowell Among My Books

JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL AMONG MY BOOKS 2008 – All rights reserved Non commercial use permitted AMONG MY BOOKS First Series by JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL * * * * * To F.D.L. Love comes and goes with music in his feet, And tunes young pulses to his roundelays; Love brings thee this: will it persuade thee, Sweet, That he turns proser when he comes and stays? * * * * * CONTENTS. DRYDEN WITCHCRAFT SHAKESPEARE ONCE MORE NEW ENGLAND TWO CENTURIES AGO LESSING ROUSSEAU AND THE SENTIMENTALISTS * * * * * DRYDEN.[1] Benvenuto Cellini tells us that when, in his boyhood, he saw a salamander come out of the fire, his grandfather forthwith gave him a sound beating, that he might the better remember so unique a prodigy. Though perhaps in this case the rod had another application than the autobiographer chooses to disclose, and was intended to fix in the pupil's mind a lesson of veracity rather than of science, the testimony to its mnemonic virtue remains. Nay, so universally was it once believed that the senses, and through them the faculties of observation and retention, were quickened by an irritation of the cuticle, that in France it was customary to whip the children annually at the boundaries of the parish, lest the true place of them might ever be lost through neglect of so inexpensive a mordant for the memory. From this practice the older school of critics would seem to have taken a hint for keeping fixed the limits of good taste, and what was somewhat vaguely called _classical_ English. To mark these limits in poetry, they set up as Hermae the images they had made to them of Dryden, of Pope, and later of Goldsmith. -

Teaching by the Book: the Culture of Reading in the George Peabody Library Gabrielle Dean

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY Teaching by the Book: The Culture of Reading in the George Peabody Library Gabrielle Dean First, there is a gasp or sigh; then the wide-eyed ing Culture in the Nineteenth-Century Library,” viewer slowly circumnavigates the building. In the which examined the intersections of the public George Peabody Library, one of the Johns Hopkins library movement, nineteenth-century book his- University’s rare book libraries, I often witness this tory and popular literature in order to describe the awe-struck response to the architecture. The library culture of reading in nineteenth-century America. interior, made largely of cast iron, illuminated by a I designed this semester-long course with two com- huge skylight and decorated with gilded neo-Gothic plementary aims in mind. and Egyptian elements, was completed in 1878 and First, I wanted to develop a new model for teach- fully expresses the aspirations of the age. It is gaudy ing American literature. Instead of proceeding from and magnificent, and it never fails to impress visitors. a set of texts deemed significant by twenty-first cen- The contents of the library are equally symbolic tury critics, our syllabus drew from the Peabody’s and grand, but less visible. The Peabody first opened collections to gain insight into what was actually to the Baltimore public in 1866 as part of the Pea- purchased, promoted and read in the nineteenth body Institute, an athenaeum-like venture set up by century. Moreover, there was no artificial separa- the philanthropist George Peabody; it originally in- tion between the texts we examined and their mate- cluded a lecture series and an art gallery in addition rial contexts. -

Download Link Source

American Historys Greatest Philanthro REATNESS. It’s a surprisingly elusive con - Three basic considerations guided our selection. Gcept. At first it seems intuitive, a superlative First, we focused on personal giving—philanthropy quality so exceptional that it cannot be conducted with one’s own money—rather than insti - missed. But when you try to define greatness, when tutional giving. Second, we only considered the you try to pin down its essence, what once seemed accomplishments attained within the individual’s obvious starts to seem opaque. own lifetime. (For that reason, we did not consider If anything, it’s even living donors, whose harder to describe greatness work is not yet finished.) in philanthropy. When it The Philanthropy Hall of Fame And third, we took a comes to charitable giving, The Roundtable is proud to announce broad view of effective - what separates the good the release of the Philanthropy Hall of ness, acknowledging from the great? Which is that excellence can take Fame, featuring full biographies of more important, the size of many forms. the gift, its percentage of American history’s greatest philan - The results of our net worth, or the return on thropists. Each of the profiles pre - research are inevitably charitable dollar? Is great sented in this article are excerpted subjective. There is a dis - philanthropy necessarily cipline, but not a science, transformative? To what from the Hall of Fame. To read more to the evaluation of great extent is effectiveness a about these seminal figures in Amer - philanthropists. Never - function of the number of ican philanthropy, please visit our new theless, we believe that individuals served, or the website at GreatPhilanthropists.org. -

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art VOLUME I THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C. A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 1 PAINTERS BORN BEFORE 1850 THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C Copyright © 1966 By The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20006 The Board of Trustees of The Corcoran Gallery of Art George E. Hamilton, Jr., President Robert V. Fleming Charles C. Glover, Jr. Corcoran Thorn, Jr. Katherine Morris Hall Frederick M. Bradley David E. Finley Gordon Gray David Lloyd Kreeger William Wilson Corcoran 69.1 A cknowledgments While the need for a catalogue of the collection has been apparent for some time, the preparation of this publication did not actually begin until June, 1965. Since that time a great many individuals and institutions have assisted in com- pleting the information contained herein. It is impossible to mention each indi- vidual and institution who has contributed to this project. But we take particular pleasure in recording our indebtedness to the staffs of the following institutions for their invaluable assistance: The Frick Art Reference Library, The District of Columbia Public Library, The Library of the National Gallery of Art, The Prints and Photographs Division, The Library of Congress. For assistance with particular research problems, and in compiling biographi- cal information on many of the artists included in this volume, special thanks are due to Mrs. Philip W. Amram, Miss Nancy Berman, Mrs. Christopher Bever, Mrs. Carter Burns, Professor Francis W. -

B-967 Peabody Institute Conservatory & George Peabody Library

B-967 Peabody Institute Conservatory & George Peabody Library Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 03-10-2011 Maryland Historical Trust Inventory No. B-967 Maryland Inventory of EASEMENT Historic Properties Form 1. Name of Property (indicate preferred name) historic Peabody Institute Conservatory and George Peabody Library (preferred) other Peabody Institute Library 2. Location street and number 1 & 17 East Mount Vernon Place not for publication city, town Baltimore vicinity county Baltimore City 3. Owner of Property (give names and mailing addresses of all owners) name JHP, Inc. c/o The Johns Hopkins University street and number 3400 N. Charles Street telephone 410-659-8100 city, town Baltimore state Maryland zip code 21218 4. -

Parker, Betty J. TITLE Educational Philanthropist George Peabody (1795-1869) and the Peabody Institute Library, Danvers, Massachusetts: Dialogue and Chronology

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 392 664 SO 025 466 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty J. TITLE Educational Philanthropist George Peabody (1795-1869) and the Peabody Institute Library, Danvers, Massachusetts: Dialogue and Chronology. PUB DATE Dec 94 NOTE 21p. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Donors; Higher Education; *Library Funding; Nonprofit Organizations; *Philanthropic Foundations; *Private Financial Support IDENTIFIERS Massachusetts (Danvers); *Peabody (George); *Peabody Institute Library MA ABSTRACT This dialogue is based on the life and success of George Peabody and the Peabody Institute Library, Danvers, Massachusetts. The dialogue is between two researchers who have spent years studying the life of George Peabody. The script recounts the difficulties faced by the poorly educated youngster who grew to become one of the wealthiest men in the United States. Peabody's educational philanthropy is recounted, along with many personal details of the man's life. A chronology of George Peabody's life is included at the end of the document. (EH) ***************7%**. **....***************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * (December 25. 1994 Draft ) Fducluional Philanthropist George Peabody (1795-1869) and the Peabody Institute Library. Dan\ers. Massachusetts: ...a,oueni arid Chronology* by Franklin and BenJ. Parker FP: We are pleased to be here in historic Danvers. Massachusetts, near where George Peabodywas born and grew up. George Peabody's branch of the family was poor. His father died in debtat age 41. From poverty. George Peabody rose to become a merchant: a broker-banker in London selling 1.1.S.state bonds to promote roads, canals. -

Names and Addresses of Living Bachelors and Masters of Arts, And

id 3/3? A3 ^^m •% HARVARD UNIVERSITY. A LIST OF THE NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF LIVING ALUMNI HAKVAKD COLLEGE. 1890, Prepared by the Secretary of the University from material furnished by the class secretaries, the Editor of the Quinquennial Catalogue, the Librarian of the Law School, and numerous individual graduates. (SKCOND YEAR.) Cambridge, Mass., March 15. 1890. V& ALUMNI OF HARVARD COLLEGE. \f *** Where no StateStat is named, the residence is in Mass. Class Secretaries are indicated by a 1817. Hon. George Bancroft, Washington, D. C. ISIS. Rev. F. A. Farley, 130 Pacific, Brooklyn, N. Y. 1819. George Salmon Bourne. Thomas L. Caldwell. George Henry Snelling, 42 Court, Boston. 18SO, Rev. William H. Furness, 1426 Pine, Philadelphia, Pa. 1831. Hon. Edward G. Loring, 1512 K, Washington, D. C. Rev. William Withington, 1331 11th, Washington, D. C. 18SS. Samuel Ward Chandler, 1511 Girard Ave., Philadelphia, Pa. 1823. George Peabody, Salem. William G. Prince, Dedham. 18S4. Rev. Artemas Bowers Muzzey, Cambridge. George Wheatland, Salem. 18S5. Francis O. Dorr, 21 Watkyn's Block, Troy, N. Y. Rev. F. H. Hedge, North Ave., Cambridge. 18S6. Julian Abbott, 87 Central, Lowell. Dr. Henry Dyer, 37 Fifth Ave., New York, N. Y. Rev. A. P. Peabody, Cambridge. Dr. W. L. Russell, Barre. 18S7. lyEpes S. Dixwell, 58 Garden, Cambridge. William P. Perkins, Wa}dand. George H. Whitman, Billerica. Rev. Horatio Wood, 124 Liberty, Lowell. 1828] 1838. Rev. Charles Babbidge, Pepperell. Arthur H. H. Bernard. Fredericksburg, Va. §3PDr. Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, 113 Boylston, Boston. Rev. Joseph W. Cross, West Boylston. Patrick Grant, 3D Court, Boston. Oliver Prescott, New Bedford. -

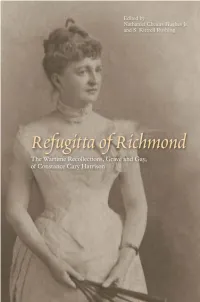

The Wartime Recollections, Grave and Gay, of Constance Cary Harrison / Edited, Annotated, and with an Introduction by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr

Refugitta of Richmond RefugittaThe Wartime Recollections, of Richmond Grave and Gay, of Constance Cary Harrison Edited by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and S. Kittrell Rushing The University of Tennessee Press • Knoxville a Copyright © 2011 by The University of Tennessee Press / Knoxville. All Rights Reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. First Edition. Originally published by Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1916. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843–1920. Refugitta of Richmond: the wartime recollections, grave and gay, of Constance Cary Harrison / edited, annotated, and with an introduction by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and S. Kittrell Rushing. — 1st ed. p. cm. Originally published under title: Recollections grave and gay. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911. Includes bibliographical references and index. eISBN-13: 978-1-57233-792-3 eISBN-10: 1-57233-792-3 1. Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843–1920. 2. United States—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Personal narratives, Confederate. 3. Virginia—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Personal narratives, Confederate. 4. United States—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Women. 5. Virginia—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Women. 6. Richmond (Va.)—History—Civil War, 1861–1865. I. Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs. II. Rushing, S. Kittrell. III. Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843-1920 Recollections grave and gay. IV. Title. E487.H312 2011 973.7'82—dc22 20100300 Contents Preface ............................................. ix Acknowledgments .....................................xiii -

Documenting Women's Lives

Documenting Women’s Lives A Users Guide to Manuscripts at the Virginia Historical Society A Acree, Sallie Ann, Scrapbook, 1868–1885. 1 volume. Mss5:7Ac764:1. Sallie Anne Acree (1837–1873) kept this scrapbook while living at Forest Home in Bedford County; it contains newspaper clippings on religion, female decorum, poetry, and a few Civil War stories. Adams Family Papers, 1672–1792. 222 items. Mss1Ad198a. Microfilm reel C321. This collection of consists primarily of correspondence, 1762–1788, of Thomas Adams (1730–1788), a merchant in Richmond, Va., and London, Eng., who served in the U.S. Continental Congress during the American Revolution and later settled in Augusta County. Letters chiefly concern politics and mercantile affairs, including one, 1788, from Martha Miller of Rockbridge County discussing horses and the payment Adams's debt to her (section 6). Additional information on the debt appears in a letter, 1787, from Miller to Adams (Mss2M6163a1). There is also an undated letter from the wife of Adams's brother, Elizabeth (Griffin) Adams (1736–1800) of Richmond, regarding Thomas Adams's marriage to the widow Elizabeth (Fauntleroy) Turner Cocke (1736–1792) of Bremo in Henrico County (section 6). Papers of Elizabeth Cocke Adams, include a letter, 1791, to her son, William Cocke (1758–1835), about finances; a personal account, 1789– 1790, with her husband's executor, Thomas Massie; and inventories, 1792, of her estate in Amherst and Cumberland counties (section 11). Other legal and economic papers that feature women appear scattered throughout the collection; they include the wills, 1743 and 1744, of Sarah (Adams) Atkinson of London (section 3) and Ann Adams of Westham, Eng.