Service Delivery-Related Unrest in South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resources Policy and Mine Closure in South Africa: the Case of the Free State Goldfields

Resources Policy 38 (2013) 363–372 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Resources Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/resourpol Resources policy and mine closure in South Africa: The case of the Free State Goldfields Lochner Marais n Centre for Development Support, University of the Free State, PO Box 339, Bloemfontein 9300, South Africa article info abstract Article history: There is increasing international pressure to ensure that mining development is aligned with local and Received 24 October 2012 national development objectives. In South Africa, legislation requires mining companies to produce Received in revised form Social and Labour Plans, which are aimed at addressing local developmental concerns. Against the 25 April 2013 background of the new mining legislation in South Africa, this paper evaluates attempts to address mine Accepted 25 April 2013 downscaling in the Free State Goldfields over the past two decades. The analysis shows that despite an Available online 16 July 2013 improved legislative environment, the outcomes in respect of integrated planning are disappointing, Keywords: owing mainly to a lack of trust and government incapacity to enact the new legislation. It is argued that Mining legislative changes and a national response in respect of mine downscaling are required. Communities & 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Mine closure Mine downscaling Local economic development Free State Goldfields Introduction areas were also addressed. According to the new Act, mining companies are required to provide, inter alia, a Social and Labour For more than 100 years, South Africa's mining industry has Plan as a prerequisite for obtaining mining rights. These Social and been the most productive on the continent. -

Uys Van Heerden

FREE DECEMBER 2016 • JANUARY 2017 SENWES EQUIPMENT AND JOHN DEERE’S GATOR WINNER Senwes Equipment and JCB – A perfect match Win with Nation in Conversation FOCUS ON Welkom & Odendaalsrus An introduction to OneAgri CHRISTMAS PERFORMANCE AND PRODUCTIVITY. SPECIAL OFFERS REDUCED RATES POSTPONED INSTALMENTS *Terms and conditions apply My choice, my Senwes. At Senwes Equipment we know what our clients want and we make sure that they get it. As the exclusive John Deere dealer we guarantee your access to the latest developments. PLEASEWe ensure CONTACTthat you have YOUR the best that money has to oer. NEAREST SENWES EQUIPMENT BRANCH FOR MORE INFO. CONTENTS ••••••• 8 31 4 CONTENTS EDITOR'S LETTER 20 Management of variables in a 2 It is raining! farming system with the assistance ON THE COVER PAGE of precision farming WHAT A YEAR 2016 has been for GENERAL 23 Meet Estelle ‘Senwes’ the newly established trademark of 3 Cartoon: Pieter & Tshepo 25 Herman is your Senwes Man – Senwes Equipment! With prize upon 3 Heard all over A grain marketing advisor with the prize they really created a Christmas 15 Christmas messages full package spirit. 26 How the handling of grain On the front page we have Gert MAIN ARTICLE changed over time? Part I 4 JCB and Senwes Equipment: A (Gerlu) Roos from Wonderfontein, 28 Branch manager Potchefstroom who won the second leg of the WIN perfect match! – Ruan brings colour to Potch BIG with Senwes Equipment and John Deere competition in Novem- 30 Utilise our Digital Platforms AREA FOCUS ber. In the process he won a John in an optimal manner 8 Welkom and Odendaalsrus Deere Gator 855D to the value of – In Circles! 46 Gert Roos wins R230 000 John R230 000, a wonderful gift, just in Deere Gator 855D time for Christmas. -

South Africa)

FREE STATE PROFILE (South Africa) Lochner Marais University of the Free State Bloemfontein, SA OECD Roundtable on Higher Education in Regional and City Development, 16 September 2010 [email protected] 1 Map 4.7: Areas with development potential in the Free State, 2006 Mining SASOLBURG Location PARYS DENEYSVILLE ORANJEVILLE VREDEFORT VILLIERS FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT VILJOENSKROON KOPPIES CORNELIA HEILBRON FRANKFORT BOTHAVILLE Legend VREDE Towns EDENVILLE TWEELING Limited Combined Potential KROONSTAD Int PETRUS STEYN MEMEL ALLANRIDGE REITZ Below Average Combined Potential HOOPSTAD WESSELSBRON WARDEN ODENDAALSRUS Agric LINDLEY STEYNSRUST Above Average Combined Potential WELKOM HENNENMAN ARLINGTON VENTERSBURG HERTZOGVILLE VIRGINIA High Combined Potential BETHLEHEM Local municipality BULTFONTEIN HARRISMITH THEUNISSEN PAUL ROUX KESTELL SENEKAL PovertyLimited Combined Potential WINBURG ROSENDAL CLARENS PHUTHADITJHABA BOSHOF Below Average Combined Potential FOURIESBURG DEALESVILLE BRANDFORT MARQUARD nodeAbove Average Combined Potential SOUTPAN VERKEERDEVLEI FICKSBURG High Combined Potential CLOCOLAN EXCELSIOR JACOBSDAL PETRUSBURG BLOEMFONTEIN THABA NCHU LADYBRAND LOCALITY PLAN TWEESPRUIT Economic BOTSHABELO THABA PATSHOA KOFFIEFONTEIN OPPERMANSDORP Power HOBHOUSE DEWETSDORP REDDERSBURG EDENBURG WEPENER LUCKHOFF FAURESMITH houses JAGERSFONTEIN VAN STADENSRUST TROMPSBURG SMITHFIELD DEPARTMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT & HOUSING PHILIPPOLIS SPRINGFONTEIN Arid SPATIAL PLANNING DIRECTORATE ZASTRON SPATIAL INFORMATION SERVICES ROUXVILLE BETHULIE -

"6$ ."*@CL9@CJ#L "6&$CG@%LC$ A=-L@68L&@@*>C

1 PHASE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA DATE: 2013-10-17 REPORT TO: ADEL GROENEWALD (Enviroworks) Tel: 086 198 8895; Fax: 086 719 7191; Postal Address: Suite 116, Private Bag X01, Brandhof, 9301; E-mail: [email protected] ANDREW SALOMON (South African Heritage Resources Agency - SAHRA) Tel: 021 462 4505; Fax: 021 462 4509; Postal Address: P.O. Box 4637, Cape Town, 8000; E-mail: [email protected] PREPARED BY: KAREN VAN RYNEVELD (ArchaeoMaps) Tel: 084 871 1064; Fax: 086 515 6848; Postal Address: Postnet Suite 239, Private Bag X3, Beacon Bay, 5205; E-mail: [email protected] THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FS ENVIROWORKS 2 SPECIALIST DECLARATION OF INTEREST I, Karen van Ryneveld (Company – ArchaeoMaps; Qualification – MSc Archaeology), declare that: o I am suitably qualified and accredited to act as independent specialist in this application; o I do not have any financial or personal interest in the application, ’ proponent or any subsidiaries, aside from fair remuneration for specialist services rendered; and o That work conducted has been done in an objective manner – and that any circumstances that may have compromised objectivity have been reported on transparently. SIGNATURE – DATE – 2013-10-17 THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FS ENVIROWORKS 3 PHASE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TERMS OF REFERENCE - Enviroworks has been appointed by the project proponent, Lebone Solar Farm (Pty) Ltd, to prepare and submit the EIA and EMPr for the proposed 75MW photovoltaic (PV) solar facility on the properties Remaining Extent of Farm Onverwag 728 and Portion 2 of Farm Vaalkranz 220 near Welkom in the Free State, South Africa. -

Ventersburg Consolidated Prospecting Right Project

VENTERSBURG CONSOLIDATED PROSPECTING RIGHT PROJECT BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAMME REPORT Submitted in support of the Prospecting Right and Environmental Authorisation Application Prepared on Behalf of: WESTERN ALLEN RIDGE GOLD MINES (PTY) LTD (Subsidiary of White Rivers Exploration (Pty) Ltd) DMR REFERENCE NUMBER: FS 30/5/1/1/3/2/1/1/10489 EM 18 APRIL 2018 Dunrose Trading 186 (PTY) Ltd T/A Shango Solutions Registration Number: 2004/003803/07 H.H.K. House, Cnr Ethel Ave and Ruth Crescent, Northcliff Tel: +27 (0)11 678 6504, Fax: +27 (0)11 678 9731 VENTERSBURG CONSOLIDATED PROSPECTING RIGHT PROJECT BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAMME REPORT Compiled by: Ms Nangamso Zizo Siwendu Environmental Consultant, Shango Solutions Cell: 072 669 6250 E-mail: [email protected] Reviewed by: Dr Jochen Schweitzer Principal Consultant, Shango Solutions Cell: 082 448 2303 E-mail: [email protected] Ms Stefanie Weise Principal Consultant, Shango Solutions Cell: 081 549 5009 E-mail: [email protected] DOCUMENT CONTROL Revision Date Report 1 12 March 2018 Draft Basic Assessment Report and Environmental Management Programme 2 18 April 2018 Final Basic Assessment Report and Environmental Management Programme DISCLAIMER AND TERMS OF USE This report has been prepared by Dunrose Trading 186 (Pty) Ltd t/a Shango Solutions using information provided by its client as well as third parties, which information has been presumed to be correct. Shango Solutions does not accept any liability for any loss or damage which may directly or indirectly result from any advice, opinion, information, representation or omission, whether negligent or otherwise, contained in this report. -

Odendaalsrus VOORNIET E 910 1104 S # !C !C#!C # !C # # # # GELUK 14 S 329 ONRUST AANDENK ZOETEN ANAS DE RUST 49 Ls HIGHLANDS Ip RUST 276 # # !

# # !C # # # ## ^ !C# !.!C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C^ # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # !C # ## # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # #!C # # # # # !C # # #^ # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # !C# ## # # #!C # # # # !C# # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # # ## # # # !C # # # ## # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# !C # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # #^ !C #!C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # !C# ^ ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C # #!C # # # # # !C# # # # # !C # # !C## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # ## # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # ^ # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # #!C # !C # # !C # # #!C # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ### # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # #### # # # !C # ## !C# # # # !C # ## !C # # # # !C # !. # # # # # # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #^ # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # ^ # !C ## # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # ## # # ## # !C # # !C## # # # ## # !C # ## # # # # # !C # # # # # !C ### # # !C# # #!C # ^ # ^ # !C # # # !C # #!C ## # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # !C## ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # !C ^ # # ## # # # # # # # # -

Mesebetsi Sampling and Administrative Variables File: Codebook

Mesebetsi Admin MESEBETSI SAMPLING AND ADMINISTRATIVE VARIABLES FILE: CODEBOOK SYSFILE INFO: \ Mesebetsi Admin data.sav File Type: SPSS 9.0 Data File Creation Date: 30 May 2000 N of Cases: 50 949 Total # of Defined Variable Elements: 63 File Contains Case Data File Is Compatible with SPSS Releases Prior to 7.5 Variable Information: Name Position RECNUM Household Record number 1 Measurement level: Scale Format: F6 Column Width: Unknown Alignment: Right ROSNUM Column number of person in HH 2 Measurement level: Scale Format: F3 Column Width: Unknown Alignment: Right RSI RSI indicator 3 Measurement level: Scale Format: F3 Column Width: Unknown Alignment: Right Value Label 0 Not RSI 1 RSI 8 RSI chosen; HH and RSI questionnaires not completed 9 Roster data valid; RSI questionnaire not completed EACODE District and EA number 4 Measurement level: Scale Format: F8 Column Width: Unknown Alignment: Right REPLIC Sample Replicate number 5 Measurement level: Scale Format: F8.2 Column Width: Unknown Alignment: Right Mesebetsi Labour Force Survey 1 Fafo Mesebetsi Admin STRATUM Sampling stratum 6 Measurement level: Scale Format: F8.2 Column Width: Unknown Alignment: Right Value Label 1.00 Urban small 2.00 Rural small 3.00 Urban Large 4.00 Rural Large 5.00 0-stratum RELWEIG2 Relative second stage estimation weight 7 Measurement level: Scale Format: F8.6 Column Width: Unknown Alignment: Right RELWEIG3 Relative third stage estimation weight 8 Measurement level: Scale Format: F8.6 Column Width: Unknown Alignment: Right EXPWEIG2 Expansion second stage estimation -

Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE ACT 51 OF 1977 Schedule of commencements relating to magisterial districts amended by magisterial districts and dates Act 122 of 1991 s. 38 (adds s. 62 (f)); Pretoria and Wonderboom: 15 August 1991; Bellville, Brits, s. 41 (a) (adds s. 276 (1) (h)); Bronkhorstspruit, Cullinan, Goodwood, The Cape, Kuils River, s. 41 (b) (adds s. 276 (3)); Mitchells Plain, Simon's Town, Soshanguve, Warmbaths and s. 42 (inserts s. 276A (1)) Wynberg: 20 March 1992; Adelaide, Albany, Alexandria, Barkly West, Bathurst, Bedford, Bloemfontein, Boshof, Bothaville, Botshabelo, Brandfort, Caledon, Calitzdorp, Camperdown, Ceres, Chatsworth, Durban, East London, Fort Beaufort, George, Groblersdal, Hankey, Hennenman, Herbert, Humansdorp, Inanda, Jacobsdal, Kimberley, King William's Town, Kirkwood, Klerksdorp, Knysna, Komga, Koppies, Kroonstad, Ladismith (Cape), Laingsburg, Lindley, Lydenburg, Malmesbury, Middelburg (Transvaal), Montagu, Mossel Bay, Moutse, Nelspruit, Oberholzer, Odendaalsrus, Oudtshoorn, Paarl, Parys, Pilgrim's Rest, Petrusburg, Pietermaritzburg, Pinetown, Port Elizabeth, Potchefstroom, Robertson, Somerset West, Stellenbosch, Strand, Sutherland, Tulbagh, Uitenhage, Uniondale, Vanderbijlpark, Ventersdorp, Vereeniging, Viljoenskroon, Vredefort, Warrenton, Welkom, Wellington, Witbank, White River and Worcester: 1 August 1992; Alberton, Barberton, Belfast, Benoni, Bergville, Bethal, Bethlehem, Bloemhof, Boksburg, Brakpan, Carolina, Coligny, Cradock, Delmas, Dundee, Eshowe, Estcourt, Frankfort, Germiston, Glencoe, Gordonia, Graaff-Reinet, -

Katleho-Winburg District Hospital Complex

KATLEHO / WINBURG DISTRICT HOSPITAL COMPLEX Introduction The Katleho-Winburg District Hospital complex is dedicated to serving the people with the outmost care, We serve the communities of Virginia, Ventersburg, Hennenman and Theunissen. Patients are referred by the clinics in the area of our hospitals, which are level 1 hospitals. In return, we refer patients to Bongani Hospital in Welkom for level 2 care. Please bring the following: UIF Certificate or affidavit from the police station, The Service is free for the following people: • Pensioners please bring proof of receiving pension i.e pension card or proof from the bank • Pregnant women and children under the age of 6 years • Disabled - please bring proof of disability/ doctors certificate Visiting Hours MONDAY- SUNDAY MORNING: 10H00 - 10H15 AFTERNOON: 15H00 - 16H00 NIGHT: 19H00 - 20H00 History of Katleho District Hospital With the Department of Health adopting a Primary Health Care approach as a vehicle for District Health Care Services, Katleho District Hospital was established in 1998 for Virginia catchment area. Katleho District Hospital previously known as Provincial Hospital Virginia, has 140 approved beds. The facility has modern equipment for service delivery at its level of care and is staffed with appropriately qualified and committed personnel. This hospital is governed by a Hospital Board History of Winburg District Hospital With the Department of Health adopting a Primary Health Care approach as a vehicle for District Health Care Services, Winburg District Hospital was established in 1998 for Winburg catchment area. Winburg District Hospital previously known as Provincial Hospital Winburg, has 055 approved beds. The facility has modern equipment for service delivery at its level of care and is staffed with appropriately qualified and committed personnel. -

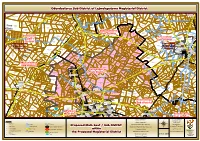

Remote Sensing Study of Soil Hazards for Odendaalsrus in the Free State Province

South African Journal of Geomatics, Vol. 4, No. 2, June 2015 Remote sensing study of soil hazards for Odendaalsrus in the Free State Province Patrick Cole1, Janine Cole2, Souleymane Diop3, Marinda Havenga4 1Council for Geoscience, Pretoria, South Africa, [email protected] 2Council for Geoscience, Pretoria, South Africa, [email protected] 3Council for Geoscience, Pretoria, South Africa, [email protected] 4Council for Geoscience, Pretoria, South Africa, [email protected] DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/sajg.v4i2.7 Abstract Expansive soils are some of the most widely distributed and costly of geological hazards. This study examined ASTER satellite data, combined with standard remote sensing techniques, namely band ratios, in identifying these soils. Ratios designed to detect various clay minerals were calculated and possible expansive soils were detected, especially in the pans. It was also possible to delineate the mudrock that may act as a source for expansive soils. Moisture content clearly affected the ratios and it shows that remote sensing can detect where wetness leads to the development of problem soils. The fact that the area has relatively dry climatic conditions may explain why large areas of the mudrock have not yet weathered to clays. Because the ratios are not unique, results can be ambiguous, so care must be taken in the interpretation phase. 1 Introduction Expansive and collapsible soils are some of the most widely distributed and costly of geological hazards. These soils are characterized by changes in volume and settlement, commonly triggered by water. The use of remote sensing data to identify these problem soils is an attractive option, being able to cover extensive areas for the identification of such hazards in a cost-effective way. -

Pnads295.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Honourable Premier of the Free State 3 Provincial Map, Free State 4 How to use the HIV-911 directory 6 SEARCH BY DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY DC20 Fezile Dabi 9 DC18 Lejweleputswa 15 DC17 Motheo 21 DC19 Thabo Mofutsanyane 31 DC16 Xhariep 39 Acknowledgements 43 Order form 44 Organisational Update Form - Update your organisational details 45 “This directory of HIV-related services in Free State is partially made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the President’s Emergency Plan.The contents are the responsibility of the Centre for HIV/AIDS Networking (through a Sub-Agreement with Foundation for Professional Development) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government” 1 HOW TO USE THE HIV-911 DIRECTORY WHO IS THE DIRECTORY FOR? This directory is for anyone who is seeking information on where to locate HIV/AIDS services and support in Free State. WHAT INFORMATION DOES THE DIRECTORY CONTAIN? Within the directory you will find information on organisations that provide HIV/AIDS-related services and support in each municipality within Free State. We have provided full contact details, an organisational overview and a listing of services for each organisation. Details on a range of HIV-related services are provided, from government clinics that dispense anti-retro- viral drugs (ARVs) and provide Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT), to faith-based and non-governmental interventions and Community Home-based Care and food parcel support programmes. HOW DO I USE THE DIRECTORY? There are close to 200 organisations working in HIV/AIDS in Free State. -

Correction of Notice

Correction of Notice Correction of the notice placed on 8 February 2018 concerning the interruption of bulk electricity supply to Mathjabeng Local Municipality Eskom hereby notifies all parties who are likely to be materially and adversely affected by its intention to interrupt bulk supply to Matjhabeng Local Municipality on 23 March 2018 and continuing indefinitely. Matjhabeng Local Municipality is currently indebted to Eskom in the amount of R1 742 710 459.06 (one billion, seven hundred and forty two million, seven hundred and ten thousand, four hundred and fifty nine rand and six cents) for the bulk supply of electricity, part of which has been outstanding and in escalation since October 2007 (“the electricity debt”). Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd (“Eskom”) is under a statutory obligation to generate and supply electricity to the municipalities nationally on a financial sustainable basis. Matjhabeng Local Municipality’s breach of its payment obligation to Eskom undermines and placed in jeopardy Eskom’s ability to continue the national supply of electricity on a financial sustainable basis. In terms of both the provisions of the Electricity Regulation Act, 4 of 2006 and supply agreement with Matjhabeng Local Municipality, Eskom is entitled to disconnect the supply of electricity of defaulting municipalities of which Matjhabeng Local Municipality is one, on account of non-payment of electricity debt. In order to protect the national interest in the sustainability of electricity supply, it has become necessary for Eskom to exercise its right to disconnect the supply of electricity to Matjhabeng Local Municipality. Eskom recognises that the indefinite disconnection of electricity supply may cause undue hardship to consumers and members of the community, and may adversely affect the delivery of other services.