Place-Based Oppositions to Development Projects Along the Ganges River and Their Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office of Mela Adhikari Kumbh, Mela Control Bhawan, C.C.R., Har Ki Pauri, Haridwar

Office of Mela Adhikari Kumbh, Mela Control Bhawan, C.C.R., Har Ki Pauri, Haridwar COMPETITION FOR LOGO DESIGN OF KUMBH MELA 2021 Haridwar 24th December 2019 The Government of Uttarakhand proposes to have a Logo for the Kumbh Mela- 2021 to be selected through open public competition. Accordingly, all Interested persons / parties (both Professional artists and Non-professionals) are hereby invited to participate in a Competition for design of the ‘Logo for Kumbh Mela-2021’. Winner will be awarded with appropriate prize money. Submission of Entries: Interested persons may send their entries via E-mail latest by 1800 hours on 25th January 2020. Entries received via any other medium and after the stipulated time shall not be entertained. The entries should be sent with subject line in submission E-Mail “Haridwar Kumbh Mela-2021 Logo Competition”. The entry should be accompanied by a brief explanation of the Design in Hindi & English Both and how it best symbolizes the Kumbh Mela-2021 and also the bio-data of the applicant. The guidelines for preparing entries, other conditions are available on the website of the Mela Adhikari (Kumbh), Haridwar https://haridwarkumbhmela2021.com & NIC Haridwar https://haridwar.nic.in Deepak Rawat, Mela Adhikari (Kumbh), Haridwar Kumbh Mela, 2021 Logo Design Competition Overview The Kumbh Mela is one of the world's largest religious gatherings. The next Kumbh Mela is scheduled to be held in Haridwar from January 2021 to April 2021. Nearly 15 crore Pilgrims are expected to visit the holy city of Haridwar during the Mela. In addition to Indian Pilgrims, the Kumbh Mela receives visitors from across the globe. -

HINDU PILGR HINDU PILGRIMAGE TOUR 15 Days / 14 Nights

HINDU PILGRIMAGE TOU R 15 Days / 14 Nights PLACES COVERED : Delhi - Haridwar - Yamunotri - Uttarkashi - Gangotri - Rudraprayag - Kedarnath - Badrinath – Delhi ITINERARY: DAY 01: ARRIVE DELHI On arrival our representative shall meet you at the airport to welcome you and transfer to hotel. Overnight hotel. Guide Map of Delhi DAY 02 DELHI Today full day city tour covering – Qutab Minar, Laxmi Narayan Temple – The Place of Gods, India Gate - The memorial of martyrs, Parliament House – The Government Headquarters. In the afternoon take a city tour of Old Delhi covering Jama Masjid - The largest mosque in Asia, Red Fort - The red stone magic, Humayun Tomb, Gandhi memorial – The memoir of father of the nation. Overnight hotel. Guide Map of Uttaranchal DAY 03 DELHI – HARIDWAR Today we shall drive you to Haridwar. On arrival check in into hotel. Later we shall take you for a visit to the Har – Ki – Pauri, enjoy the “AARTI” in the evening. Later back to hotel for overnight stay at the hotel. DAY 04 HARIDWAR – SYANA CHATTI Today we shall drive you to Syana Chatti – a scenic spot on the banks of River Yamuna. Overnight hotel. DAY 05 SYANA CHATTI – YAMNOTRI – SYANA CHATTI 5kms By Road & 13 Kms trek one side. Drive to Hanuman Chatti, trek start to Yamun otri & Back. Overnight stay at Syana Chatti. Hanuman Chatti: The confluence of Hanuman Ganga & Yamuna River. Yamunotri Temple: Maharani Gularia of Jaipur built the temple in the 19th Century. It was destroyed twice in the present century and rebuilt again. Surya Kund: There are a Number of thermal springs in the vicinity of the temple, which flows into numerous pools. -

Yamunotri Gangotri Yatra (DT #259)

Yamunotri Gangotri Yatra (DT #259) Price: 0.00 => Pilgrimage => India => 06 Nights / 07 Days => Breakfast, Sightseeing, Accomodation, Transfers Overview Day 01: Delhi - Haridwar (230 kms/6-7hrs) HT : 314 MTS.Arrival Delhi Airport / Delhi Railway Station, Meet Assist further drive to Haridwar. Transfer to your Hotel. If time permits visit Bharat Mata Mandir, Bhuma Niketan, India Temple, Pawan Dham, Doodhadhari Temple others. Later visit Har-ki-Pauri for Ganga Aarti. The 'Aarti' worship of the Ganga after sunset and the floating 'dia' (lamp) is a moving ritual.Back to your hotel, Night halt.Haridwar, lying at the feet of Shiva's hills, i.e., Shivaliks, in the Haridwar district of Uttaranchal Pradesh, is a doorway. Suryavanshi prince Bhagirath performed penance here to salvage the souls of his ancestors who had perished due to the curse of sage Kapila. The penance was answered and the riverGangatrickled forth forms Lord Shiva's locks and its bountiful water revived the sixty thousand sons of king Sagara. In the traditional of Bhagirath, devout Hindus stand in the sacred waters here, praying for salvation of their departed elder. It is doorway to the sources of the Ganga and the Yamuna, 3000 to 4500 meters up into the snowy ranges of the central Himalayas.Weather - Generally hot in summer, the temperature ranges from 35-40 degree Celsius, Winter: The Days are pleasantly cool but the nights are cold, temp ranges from 20 deg to 05 deg.Day 02: Haridwar - Barkot (210kms/7-8hr) HT : 1352 MTS.Drive to Barkot via Mussoorie, enroute visit Kempty Fall (Suggestible to have your lunch at Kempty fall as further no good restaurants are available before Badkot). -

Comprehensive Mobility Plan for Dehradun

COMPREHENSIVE MOBILITY PLAN FOR DEHRADUN - RISHIKESH – HARIDWAR METROPOLITAN AREA May 2019 Comprehensive Mobility Plan For Dehradun - Rishikesh – Haridwar Metropolitan Area Quality Management Report Prepared Report Report Revision Date Remarks By Reviewed By Approved By 2018 1 Ankush Malhotra Yashi Tandon Mahesh Chenna S.Ramakrishna N.Sheshadri 10/09/2018 Neetu Joseph (Project Head) (Reviewer) Nishant Gaikwad Midhun Sankar Mahesh Chenna Neetu Joseph Nishant Gaikwad S.Ramakrishna N.Sheshadri 2 28/05/2019 Hemanga Ranjan (Project Head) (Reviewer) Goswami Angel Joseph TABLE OF CONTENTS Comprehensive Mobility Plan for Metropolitan Area focusing Dehradun-Haridwar-Rishikesh TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMARY...........................................................................................i 1 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 14 1.1 Study Background ......................................................................................................................... 14 1.2 Need for Comprehensive Mobility Plan ........................................................................................ 15 1.3 Objectives and Scope of the Study ................................................................................................ 16 1.4 Study Area Definition .................................................................................................................... 19 1.5 Structure of the Report ................................................................................................................ -

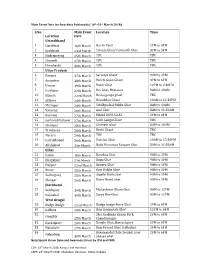

S.No Location Main Event Date Location Time Uttarakhand 1

Main Event Date for Swachhta Pakhwada ( 16th-31st March 2018) S.No Main Event Location Time Location Date Uttarakhand 1 Haridwar 16th March Har ki Pauri 2PM to 6PM 2 Rishikesh 23rd March Triveni Ghat/ Parmarth Ghat 3PM to 5PM 3 Rudraprayag 25th March TBC TBC 4 Chamoli 27th March TBC TBC 5 Uttrakashi 30th March TBC TBC Uttar Pradesh 6 Kanpur 17th March Sarsaiya Ghaat 9AM to 2PM 7 Anupshar 18th March Bacchi Gaon Ghaat 3PM to 6PM 8 Unnao 19th March Buxer Ghat 12PM to 2:30PM 9 Fatehpur 20th March Om Ghat, Bhetaura 8AM to 10AM 10 Bijnore 22nd March Bairaj ganga ghaat TBC 11 Bithoor 24th March Brumbhut Ghaat 10AM to 12:30PM 12 Mirzapur 24th March Vindhyachal Pakka Ghat 8AM to 10AM 13 Varanasi 26th March Assi Ghat 8AM to 11:30AM 14 Kannauj 27th March MAHA DEVI GHAT 2PM to 4PM 15 Garhmukteshwar 27th March Garh Ganga Ghaat TBC 16 Ghazipur 28th March Chitnath Ghat 8AM to 10AM 17 Vrindavan 28th March Keshi Ghaat TBC 18 Narora 29th March TBC TBC 19 Farrukhabad 30th March Panchal Ghat 10AM to 12:30PM 20 Allahabad 31st March Bada Hanuman Sangam Ghat 8AM to 11:30AM Bihar 21 Patna 18th March Barahua Ghat 9AM to 1PM 22 Bhagalpur 21st March Kupa Ghat 9AM to 1PM 23 Hajipur 22nd March Konara Ghat 9AM to 1PM 24 Buxar 25th March Ram Rekha Ghat 9AM to 1PM 25 Sultanganj 25th March Ajgaibi Nath Ghat 9AM to 1PM 26 Munger 26th March Kasta Harni Ghat 9AM to 1PM Jharkhand 27 Sahibganj 19th March Multeshwar Dham Ghat 9AM to 12PM 28 Rajmahal 30th March Surya Dev Ghat 9AM to 12PM West Bengal 29 Budge Budge 22nd March Budge budge Ferry Ghat 2PM to 6PM 30 Kolkata 24th March Baje Kadamtala Ghat 12PM to 4PM 31 Shri Arabinda Kanan Park, 2PM to 6PM Hooghly 25th March Chandarnagar 32 Barackpore 26th March Gandhi Ghat, Barrackpore 2PM to 6PM 33 Halishahr 27th March Ram Prasad Ghat, Halisahar 2PM to 6PM 34 Karamandal Club Ground, near 2PM to 6PM Nabadwip 30th March Shasan Ghat Note:Special Shram Daan and Awareness Drives by CISF and CRPF CISF: 18th March 2018: Kanpur and Haridwar CRPF: 24th March 2018: Allahabad, Varanasi., Patna, Kolkata . -

Hemkund Sahib

Bhimtal Kausani Binsar Hemkund Sahib Auli Bhimtal, a serene hill station, is a popular destination lying at about 25 kms Called as 'Switzerland of India' by Mahatma Gandhi, the beautiful hill station, Binsar is located at a distance of about 30 kms from Almora; it used to be the Hemkund Sahib is located at an altitude of 4329 m amid pristine environs. A 5 Auli is a beautiful ski town that can be reached by road, or by ropeway from from Nainital . Watch the flock of ducks revelling in the crystal clear water of Kausani opens up the panaroma of Someshwar Valley on the one side and summer capital of the Chand kings. The place gets its name from the famous to 6 hours steep climb from Ghanghria would bring one to this holy spot. With Joshimath. Its terrain is considered to be excellent for skiing, even by Bhimtal lake. With a picturesque location in the midst of green kumaoni hills, it Garur and Baijnath Katyuri Valley on the others. it was his favourite home 16th century Bineshwar Mahadev Temple. snow - capped peaks and glaciers all around, its clear waters reflect the international standards. The facility is available in winter, while in summer it is reasonably pleasant in summers ; makes for a great holiday, nevertheless. within the mountains; he stayed at the Anashakti Ashram for Yoga in early 20th surroundings. One of the most important pilgrimage spots for Sikhs and assumes a very picturesque look. Nandadevi and Kamet are a visual delight One of the largest lakes in the state, Bhimtal was named after Bhim, a century, and commented that Kausani was the perfect resort for seekers of Hindus, Hemkund Sahib houses a Gurudwara; the Lakshman temple lies when viewed from the lap of Auli Bugyal. -

Assessment of Noise Pollution in Haridwar City of Uttarakhand State, India During Kumbh Mela 2010 and Its Impact on Human Health

AL SCI 293 UR EN T C A E N F D O N U A N D D A E I Journal of Applied and Natural Science 2 (2): 293-295 (2010) T L I O P N P A JANS ANSF 2008 Assessment of noise pollution in Haridwar city of Uttarakhand State, India during Kumbh Mela 2010 and its impact on human health S. Madan* and Pallavi Department of Environmental Sciences, Kanya Gurukula Mahavidhyalaya, Gurukula Kangri Vishwavidyalaya, Haridwar- 249404, INDIA. *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract:The present study was carried to investigate the noise level at four different locations of Haridwar viz. Singh Dwar, Rishikul, Chandi ghat and Har Ki Pauri during Kumbh Mela 2010. During normal days maximum noise levels were recorded at Chandi ghat i.e. 87.11±0.45 dB (A) in the evening hours and minimum noise levels were recorded at Har Ki Pauri i.e. 60.8±0.89 dB (A) in the morning hours. While during festival days maximum noise levels were at Har Ki Pauri i.e. 88.4 ± 1.65 dB (A) in the evening respectively and Rishikul the least being 54.93±0.53 dB (A) in the morning hours. Noise levels in all the areas were found to be above the ambient noise standard. These high noise levels may have induced headache, annoyance, lack of concentration and other varied effects on human health. Keywords: Kumbh Mela, Noise levels, Ambient noise, Haridwar INTRODUCTION MATERIALS AND METHODS Noise is a potential hazard to health, communication and Study Sites: The present study was conducted from enjoyment of social life slowly, but surely noise is January-2010 to March-2010 during the religious Khumb becoming an unjustifiable interference and imposition Mela with the help of portable precision sound level meter upon human comfort, health and quality of life. -

Duration: 11 Nights / 12 Days Places Covered: Delhi

Duration: 11 Nights / 12 Days Places Covered: Delhi - Rishikesh - Barkot - Yamunotri - Uttarkashi - Gangotri - Guptkashi - Kedarnath - Pipalkoti - Badrinath - Srinagar - Haridwar - Delhi Day 01: Delhi - Rishikesh (230 kms/6hrs) In the morning drive from Delhi to Rishikesh. Halt for enrooted lunch at Marwari Point. Continue your drive and upon arrival check- in at the hotel. In the evening view Ganga Aarti the pleasant ritual of worshipping the Ganga at Parmarth Niketan and stay overnight at the hotel. Day 02: Rishikesh - Barkot (200 kilometers/7hr) After breakfast drive to Barkot via Mussoorie visiting Kempty Falls on the way. Continue your drive until you reach Barkot and upon arrival check-in at the hotel. Day 03: Barkot - Yamunotri - Barkot - 36kms drive & 7kms Trek (one side) In the morning trip will start by driving to Janki Chatti; the holy thermal spring and start trek to Yamunotri wherein you have an option to either walk or sit on horseback or by Doli at your own cost. Arrive Yamunotri: It is the source of Yamuna River and the place of the Goddess Yamuna. The Yamunotri Dham is the blessed journey at the height of 3293 meters at Uttarkashi district in Uttarakhand dedicated to Goddess Yamuna. After taking bath in Jamunabai Kund’s warm water and having “Darshan” of pious “Yamunaji” return to Hanumanchatti. Later drive back to Barkot. Overnight stay at Hotel. Hanuman Chatti: Considered to be a popular trekking spot and is one of the thrilling climb in the rocky terrain, located 13 kilometers away from the Yamunotri temple offers splendid beauty to the visitors as this peaceful place is spotted at the confluence of the magnificent rivers Yamuna and Hanuman Ganga. -

DO DHAM YATRA 7 Days/6 Nights

DO DHAM YATRA 7 Days/6 Nights- 1 night Haridwar, 2 Night Guptakashi, 2 Nights Joshimath, 1 Night Rishikesh Description In the folds of the snow-covered reaches of the lofty Garhwal Himalayas in Uttarakhand are located the sacred Hindu shrines of Badrinath, Kedarnath, Gangotri and Yamunotri. They together form the Char Dham or the Four Holy Shrines. The region is referred as the land of the gods in the ancient Puranas. Scores of pilgrims visit the shrines by trekking arduously along the mountain paths, all for a communion with the divine. Over the centuries, these sites have been described in sacred scriptures as the very places where devotees could earn the merits of all the pilgrimages put together. Subsequently, temples were built at these sanctified sties for all and sundry. Tour Highlights Haridwar Haridwar or hari- dwar in hindi literally means gateway to god. This holy place is a famous religious destination that invites people of various faith and background. Haridwar depicts Indian culture and civilization in its full effect. Haridwar opens the doors to char dham or the four religious centers badrinath, kedaenath, gangotri and yamunotri. Badrinath Snuggled between two famous mountain ranges, Nar and Narayan, Badrinath is situated in the Chamoli district of Uttarakhand. It is the famous Char Dham pilgrimage in Uttarakhand. The term ‘Badrinath’ means ‘the place where berries grow in abundance’. Legend has it that two sages, Nar and Narayan, performed severe penance to please Lord Page 1/6 Shiva. Famous for the holy shrine of Lord Badri, this holy abode of Lord Vishnu is visited by people for its omnipresent spirituality and beauty. -

IBEF Presentataion

UTTARAKHAND THE SPIRITUAL SOVEREIGN OF INDIA For updated information, please visit www.ibef.org July 2017 Table of Content Executive Summary .…………….….…….3 Advantage State ……..……………………4 Uttarakhand Vision ……………….……….5 Uttarakhand – An Introduction …….……..6 Annual State Budget 2015–16 ………….16 Infrastructure Status ...............................17 Business Opportunities ……..………......41 Doing Business in Uttarakhand …………58 State Acts & Policies …….………...........63 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Evolving . Uttarakhand has witnessed massive growth in capital investments due to a conducive industrial policy and industrialisation generous tax benefits. Therefore, Uttarakhand is one of the fastest growing states in India. The state’s GSDP facilitating growth increased at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.38% during 2011-12 to 2016-17. The state is situated in the foothills of Himalayas. The presence of several hill stations, wildlife parks, Thriving tourism pilgrimage places & trekking routes make Uttarakhand an attractive tourist destination. Inflow of foreign tourists into the state increased from 101.97 thousand in 2014-15 to 105.88 thousand in 2015-16. Hydropower generation . Uttarakhand is being developed as an ‘energy state’ to tap the hydropower electric potential of over 25,000 potential MW. During 2016-17, hydropower generation installed capacity in the state was recorded to be 1,815.69 MW. Forest sector on . Forest area covers about 71.05% of the state. The state’s forest revenues increased at a CAGR of 9.5% growth path between 2004-05 and 2013-14 and reached US$ 64.67 million in 2014-15. Floriculture and . Uttarakhand has almost all agro-geo climatic zones, which provide commercial opportunities for floriculture horticulture and horticulture. -

Uttarakhand Tourism Development Board Pt.Deendayal Upadhaya Paryatan Bhawan Near ONGC Helipad, Garhi Cantt, Dehradun, Uttarakhand 248001

Uttarakhand Tourism Development Board Pt.Deendayal Upadhaya Paryatan Bhawan Near ONGC Helipad, Garhi Cantt, Dehradun, Uttarakhand 248001. Email: [email protected]; Tel: +91-135 255 9987, Fax: +91-135 – 2559988 CHAR DHAM YATRA Destinations: Haridwar, Yamunotri, Gangotri, Kedarnath, Badrinath Duration: 10 nights, 11 days Distance: Over 2,000 km from Delhi For Family and Group Travel Experiences: Trekking Budget: Approx INR 35,000 (per person, by road) Start Day 01 DELHI TO HARIDWAR Start from Delhi as early as possible so that you reach Haridwar by afternoon. Check into your hotel take some rest and in the evening, visit Har Ki Pauri Ghat to enjoy the serene Ganga aarti (a divine ritual). Walk around the temple and enjoy the evening breeze, the tolling of bells and holy chants. Retire to bed early. Car: Haridwar is connected to other parts of India with a wide network of roads. From Delhi, the distance is around 220 km and it takes about five to six hours by road. There are several refreshment stops on the way and it’s a smooth drive. Train: Haridwar Railway Station connects to a lot of cities across India. Airport: Jolly Grant Airport is 37 km from Haridwar. It connects to all major cities in India. Day 02 HARIDWAR TO BARKOT Have breakfast and leave early for Barkot. You will take the route via Dehradun and Mussoorie. En route, stop at Kempty Falls and then continue the drive to Barkot. Keep about an hour extra in hand to explore Kempty Falls and the several beautiful stops along the way to click photographs. -

Uttarakhand Tourism Development Master Plan 2007 - 2022

Government of India Government of Uttarakhand United Nations Development Programme World Tourism Organization Uttarakhand Tourism Development Master Plan 2007 - 2022 Final Report Volume I - Executive Summary April 2008 Uttarakhand Tourism Development Master Plan Executive Summary Table of Contents Volume 1 - Executive Summary 1. Introduction and Background 6 2. Current Tourism Scenario in Uttarakhand 10 3. Tourism Zones 15 4. Strategies 30 5. Implementing Strategies by Actions and Interventions 73 6. Action Plans 101 Volume 2 - Main Report Acknowledgements The following constitutes a list of persons who have contributed towards the formulation of Uttarakhand Tourism Development Master Plan in one or the other way. The consultant team would like to express its appreciation of the valuable contributions made by the many people met along the way in the progression of the master plan work in Delhi, Dehradun and not least during the many field trips in the Garhwal and Kumaon Regions. 1. From Ministry of Tourism, Government of India Dr. S. Banerjee, Secretary Mr. Sanjay Kothari, Additional Director General Mr. Rajesh Talwar, Assistant Director General 2. From State Government of Uttarakhand Hon. Prakash Pant, Minister for Tourism and Religious Works Mr. I. K. Pande, Additional Chief Secretary and Principal Secretary of Tourism Mr. Rakesh Sharma, Principal Secretary of Tourism Ms. Hemlata Dondiyal, Additional Secretary, Tourism Mr. Amarendra Sinha, Secretary Ms. Vibha Puri Das, Principal Secretary & Commissioner, Forest & Rural Development Mrs. Vena Seshechi, Chief Conservator of Forests, Forest Department Mr. S. Ramaswamy, Secretary & Commissioner, Transport Mr. Ahatrughna Singh, Secretary, Power, Housing & Urban Development Mr. L. H. Indrasiri, Director, Information Systems & GIS Mr.