The Natural History of Madagascar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wing Polymorphism in European Species of Sphaeroceridae (Diptera)

ACTA ENTOMOLOGICA MUSEI NATIONALIS PRAGAE Published 17.xii.2012 Volume 52( 2), pp. 535–558 ISSN 0374-1036 Wing polymorphism in European species of Sphaeroceridae (Diptera) Jindřich ROHÁČEK Slezské zemské muzeum, Tyršova 1, CZ-746 46 Opava, Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The wing polymorphism is described in 8 European species of Sphae- roceridae (Diptera), viz. Crumomyia pedestris (Meigen, 1830), Phthitia spinosa (Collin, 1930), Pteremis fenestralis (Fallén, 1820), Pullimosina meijerei (Duda, 1918), Puncticorpus cribratum (Villeneuve, 1918), Spelobia manicata (Richards, 1927), Spelobia pseudonivalis (Dahl, 1909) and Terrilimosina corrivalis (Ville- neuve, 1918). These cases seem to belong to three types of alary polymorphism: i) species with separate macropterous and brachypterous forms – Crumomyia pedestris, Pteremis fenestralis, Pullimosina meijerei; ii) species with a continual series of wing forms ranging from brachypterous to macropterous – Puncticor- pus cribratum, Spelobia pseudonivalis, Terrilimosina corrivalis; iii) similar to the foregoing type but with only slightly reduced wing in the brachypterous form – Phthitia spinosa, Spelobia manicata. The variability of venation of wing polymorphic and brachypterous species of the West-Palaearctic species of Sphaeroceridae was examined and general trends in the reduction of veins during evolution are defi ned. These trends are found to be different in Copromyzinae (C. pedestris) and Limosininae (all other species) where 6 successive stages of reduction are recognized. The fi rst case of a specimen (of Pullimosina meije- rei) with unevenly developed wings (one normal, other reduced) is described in Sphaeroceridae. Causes of the origin of wing polymorphism, variability of wing polymorphic populations depending on geographical and climatic factors, importance of wing polymorphism in the evolution of brachypterous and apterous species and the probable genetic background of wing polymorphism in European species are discussed. -

Identification Key for Mosquito Species

‘Reverse’ identification key for mosquito species More and more people are getting involved in the surveillance of invasive mosquito species Species name used Synonyms Common name in the EU/EEA, not just professionals with formal training in entomology. There are many in the key taxonomic keys available for identifying mosquitoes of medical and veterinary importance, but they are almost all designed for professionally trained entomologists. Aedes aegypti Stegomyia aegypti Yellow fever mosquito The current identification key aims to provide non-specialists with a simple mosquito recog- Aedes albopictus Stegomyia albopicta Tiger mosquito nition tool for distinguishing between invasive mosquito species and native ones. On the Hulecoeteomyia japonica Asian bush or rock pool Aedes japonicus japonicus ‘female’ illustration page (p. 4) you can select the species that best resembles the specimen. On japonica mosquito the species-specific pages you will find additional information on those species that can easily be confused with that selected, so you can check these additional pages as well. Aedes koreicus Hulecoeteomyia koreica American Eastern tree hole Aedes triseriatus Ochlerotatus triseriatus This key provides the non-specialist with reference material to help recognise an invasive mosquito mosquito species and gives details on the morphology (in the species-specific pages) to help with verification and the compiling of a final list of candidates. The key displays six invasive Aedes atropalpus Georgecraigius atropalpus American rock pool mosquito mosquito species that are present in the EU/EEA or have been intercepted in the past. It also contains nine native species. The native species have been selected based on their morpho- Aedes cretinus Stegomyia cretina logical similarity with the invasive species, the likelihood of encountering them, whether they Aedes geniculatus Dahliana geniculata bite humans and how common they are. -

Evaluation of Seedling Tray Drench of Insecticides for Cabbage Maggot (Diptera: Anthomyiidae) Management in Broccoli and Cauliflower

Evaluation of seedling tray drench of insecticides for cabbage maggot (Diptera: Anthomyiidae) management in broccoli and cauliflower Shimat V. Joseph1,*, and Shanna Iudice2 Abstract The larval stages of cabbage maggot, Delia radicum (L.) (Diptera: Anthomyiidae), attack the roots of cruciferous crops and often cause severe eco- nomic damage. Although lethal insecticides are available to controlD. radicum, efficacy can be improved by the placement of residues near the roots where the pest is actively feeding and causing injury. One such method is drenching seedlings with insecticide before transplanting, referred to as “tray drench.” The efficacy of insecticides, when applied as tray drench, is not thoroughly understood for transplants of broccoli and cauliflower. Thus, a series of seedling tray drench trials were conducted on transplants of these 2 vegetables using cyantraniliprole, chlorantraniliprole, clothianidin, bifenthrin, flupyradifurone, chlorpyrifos, and spinetoram in greenhouse and field settings. In the greenhouse trials, the severityD. of radicum feeding injury was significantly lower on broccoli and cauliflower transplants when drenched with clothianidin, bifenthrin, and cyantraniliprole compared with untreated controls. In broccoli field trials, incidence and severity of feeding injury was lower in seedlings drenched with cyantraniliprole and clothianidin, as well as a clothianidin spray at the base of seedlings, than the use of spinetoram, chlorpyrifos, flupyradifurone, and chlorantraniliprole. In a cauliflower field trial, -

The Occurrence of Stalk-Eyed Flies (Diptera, Diopsidae) in the Arabian Peninsula, with a Review of Cluster Formation in the Diopsidae Hans R

Tijdschrift voor Entomologie 160 (2017) 75–88 The occurrence of stalk-eyed flies (Diptera, Diopsidae) in the Arabian Peninsula, with a review of cluster formation in the Diopsidae Hans R. Feijen*, Ralph Martin & Cobi Feijen Catalogue and distribution data are presented for the six Diopsidae species known to occur in the Arabian Peninsula: Sphyracephala beccarii, Chaetodiopsis meigenii, Diasemopsis aethiopica, Diopsis arabica, Diopsis mayae and Diopsis sp. (ichneumonea species group). The biogeographical aspects of their distribution are discussed. Records of Diopsis apicalis and Diopsis collaris are removed from the list for Arabia as these were based on misidentifications. Synonymies involving Diasemopsis aethiopica and Diasemopsis varians are discussed. Only one out of four specimens in the D. elegantula type series proved conspecific with D. aethiopica. The synonymy of D. aethiopica and D. varians is rejected. A lectotype for Diasemopsis elegantula is now designated. D. elegantula is proposed as junior synonym of D. varians. A fly cluster of more than 80,000 Sphyracephala beccarii, observed in Oman, is described. The occurrence of cluster formations in the Diopsidae is reviewed, while a possible explanation is indicated. Hans R. Feijen*, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands. [email protected] Ralph Martin, University of Freiburg, Münchhofstraße 14, 79106 Freiburg, Germany Cobi Feijen, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands Introduction catalogue for Diopsidae, Steyskal (1972) only re- Westwood (1837b) described Diopsis arabica as ferred to Westwood and Hennig as far as Diopsidae the first stalk-eyed fly from the Arabian Peninsula. in Arabia was concerned. -

Insects Commonly Mistaken for Mosquitoes

Mosquito Proboscis (Figure 1) THE MOSQUITO LIFE CYCLE ABOUT CONTRA COSTA INSECTS Mosquitoes have four distinct developmental stages: MOSQUITO & VECTOR egg, larva, pupa and adult. The average time a mosquito takes to go from egg to adult is five to CONTROL DISTRICT COMMONLY Photo by Sean McCann by Photo seven days. Mosquitoes require water to complete Protecting Public Health Since 1927 their life cycle. Prevent mosquitoes from breeding by Early in the 1900s, Northern California suffered MISTAKEN FOR eliminating or managing standing water. through epidemics of encephalitis and malaria, and severe outbreaks of saltwater mosquitoes. At times, MOSQUITOES EGG RAFT parts of Contra Costa County were considered Most mosquitoes lay egg rafts uninhabitable resulting in the closure of waterfront that float on the water. Each areas and schools during peak mosquito seasons. raft contains up to 200 eggs. Recreational areas were abandoned and Realtors had trouble selling homes. The general economy Within a few days the eggs suffered. As a result, residents established the Contra hatch into larvae. Mosquito Costa Mosquito Abatement District which began egg rafts are the size of a grain service in 1927. of rice. Today, the Contra Costa Mosquito and Vector LARVA Control District continues to protect public health The larva or ÒwigglerÓ comes with environmentally sound techniques, reliable and to the surface to breathe efficient services, as well as programs to combat Contra Costa County is home to 23 species of through a tube called a emerging diseases, all while preserving and/or mosquitoes. There are also several types of insects siphon and feeds on bacteria enhancing the environment. -

Burmese Amber Taxa

Burmese (Myanmar) amber taxa, on-line supplement v.2021.1 Andrew J. Ross 21/06/2021 Principal Curator of Palaeobiology Department of Natural Sciences National Museums Scotland Chambers St. Edinburgh EH1 1JF E-mail: [email protected] Dr Andrew Ross | National Museums Scotland (nms.ac.uk) This taxonomic list is a supplement to Ross (2021) and follows the same format. It includes taxa described or recorded from the beginning of January 2021 up to the end of May 2021, plus 3 species that were named in 2020 which were missed. Please note that only higher taxa that include new taxa or changed/corrected records are listed below. The list is until the end of May, however some papers published in June are listed in the ‘in press’ section at the end, but taxa from these are not yet included in the checklist. As per the previous on-line checklists, in the bibliography page numbers have been added (in blue) to those papers that were published on-line previously without page numbers. New additions or changes to the previously published list and supplements are marked in blue, corrections are marked in red. In Ross (2021) new species of spider from Wunderlich & Müller (2020) were listed as being authored by both authors because there was no indication next to the new name to indicate otherwise, however in the introduction it was indicated that the author of the new taxa was Wunderlich only. Where there have been subsequent taxonomic changes to any of these species the authorship has been corrected below. -

Diptera, Acroceridae

Accepted Manuscript Anchored phylogenomics unravels the evolution of spider flies (Diptera, Acro- ceridae) and reveals discordance between nucleotides and amino acids Jessica P. Gillung, Shaun L. Winterton, Keith M. Bayless, Ziad Khouri, Marek L. Borowiec, David Yeates, Lynn S. Kimsey, Bernhard Misof, Seunggwan Shin, Xin Zhou, Christoph Mayer, Malte Petersen, Brian M. Wiegmann PII: S1055-7903(18)30223-9 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.08.007 Reference: YMPEV 6254 To appear in: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution Received Date: 5 April 2018 Revised Date: 3 August 2018 Accepted Date: 7 August 2018 Please cite this article as: Gillung, J.P., Winterton, S.L., Bayless, K.M., Khouri, Z., Borowiec, M.L., Yeates, D., Kimsey, L.S., Misof, B., Shin, S., Zhou, X., Mayer, C., Petersen, M., Wiegmann, B.M., Anchored phylogenomics unravels the evolution of spider flies (Diptera, Acroceridae) and reveals discordance between nucleotides and amino acids, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution (2018), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.08.007 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. Anchored phylogenomics unravels the evolution of spider flies (Diptera, Acroceridae) and reveals discordance between nucleotides and amino acids Jessica P. -

Zootaxa, Diptera, Opomyzoidea

Zootaxa 1009: 21–36 (2005) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1009 Copyright © 2005 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Curiosimusca, gen. nov., and three new species in the family Aul- acigastridae from the Oriental Region (Diptera: Opomyzoidea) ALESSANDRA RUNG, WAYNE N. MATHIS & LÁSZLÓ PAPP (AR) Department of Entomology, 4112 Plant Sciences Building, University of Maryland, College Park, Mary- land 20742, United States. E-mail: [email protected]. (WNM) Department of Entomology, NHB 169, PO BOX 37012, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, United States. E-mail: [email protected]. (LP) Zoological Department, Hungarian Natural History Museum, Baross utca 13, PO BOX 137, 1431 Budapest, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract A new genus, Curiosimusca, and three new species (C. khooi, C. orientalis, C. maefangensis) are described from specimens collected in the Oriental Region (Malaysia, Thailand). Curiosimusca is postulated to be the sister group of Aulacigaster Macquart and for the present is the only other genus included in the family Aulacigastridae (Opomyzoidea). Morphological evidence is presented to document our preliminary hypothesis of phylogenetic relationships. Key words: Aulacigastridae, Diptera, systematics, Oriental Region Introduction While preparing a monograph on the family Aulacigastridae (Rung & Mathis in prep.), we discovered several specimens of enigmatic flies from Malaysia and Thailand. The speci- mens from Malaysia had been identified and labeled as “possibly Aulacigastridae.” Our subsequent study of these specimens has revealed them to be the closest extant relatives of Aulacigaster Macquart, which until now has been the only recently included genus in the family Aulacigastridae. -

1 U of Ill Urbana-Champaign PEET

U of Ill Urbana-Champaign PEET: A World Monograph of the Therevidae (Insecta: Diptera) Participant Individuals: CoPrincipal Investigator(s) : David K Yeates; Brian M Wiegmann Senior personnel(s) : Donald Webb; Gail E Kampmeier Post-doc(s) : Kevin C Holston Graduate student(s) : Martin Hauser Post-doc(s) : Mark A Metz Undergraduate student(s) : Amanda Buck; Melissa Calvillo Other -- specify(s) : Kristin Algmin Graduate student(s) : Hilary Hill Post-doc(s) : Shaun L Winterton Technician, programmer(s) : Brian Cassel Other -- specify(s) : Jeffrey Thorne Post-doc(s) : Christine Lambkin Other -- specify(s) : Ann C Rast Senior personnel(s) : Steve Gaimari Other -- specify(s) : Beryl Reid Technician, programmer(s) : Joanna Hamilton Undergraduate student(s) : Claire Montgomery; Heather Lanford High school student(s) : Kate Marlin Undergraduate student(s) : Dmitri Svistula Other -- specify(s) : Bradley Metz; Erica Leslie Technician, programmer(s) : Jacqueline Recsei; J. Marie Metz Other -- specify(s) : Malcolm Fyfe; David Ferguson; Jennifer Campbell; Scott Fernsler Undergraduate student(s) : Sarah Mathey; Rebekah Kunkel; Henry Patton; Emilia Schroer Technician, programmer(s) : Graham Teakle Undergraduate student(s) : David Carlisle; Klara Kim High school student(s) : Sara Sligar Undergraduate student(s) : Emmalyn Gennis Other -- specify(s) : Iris R Vargas; Nicholas P Henry Partner Organizations: Illinois Natural History Survey: Financial Support; Facilities; Collaborative Research Schlinger Foundation: Financial Support; In-kind Support; Collaborative Research 1 The Schlinger Foundation has been a strong and continuing partner of the therevid PEET project, providing funds for personnel (students, scientific illustrator, data loggers, curatorial assistant) and expeditions, including the purchase of supplies, to gather unknown and important taxa from targeted areas around the world. -

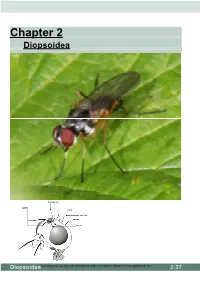

Chapter 2 Diopsoidea

Chapter 2 Diopsoidea DiopsoideaTeaching material only, not intended for wider circulation. [email protected] 2:37 Diptera: Acalyptrates DIOPSOI D EA 50: Tanypezidae 53 ------ Base of tarsomere 1 of hind tarsus very slightly projecting ventrally; male with small stout black setae on hind trochanter and posterior base of hind femur. Postocellar bristles strong, at least half as long as upper orbital seta; one dorsocentral and three orbital setae present Tanypeza ----------------------------------------- 55 2 spp.; Maine to Alberta and Georgia; Steyskal 1965 ---------- Base of tarsomere 1 of hind tarsus strongly projecting ventrally, about twice as deep as remainder of tarsomere 1 (Fig. 3); male without special setae on hind trochanter and hind femur. Postocellar bristles weak, less than half as long as upper orbital bristle; one to three dor socentral and zero to two orbital bristles present non-British ------------------------------------------ 54 54 ------ Only one orbital bristle present, situated at top of head; one dorsocentral bristle present --------------------- Scipopeza Enderlein Neotropical ---------- Two or three each of orbital and dorsocentral bristles present ---------------------Neotanypeza Hendel Neotropical Tanypeza Fallén, 1820 One species 55 ------ A black species with a silvery patch on the vertex and each side of front of frons. Tho- rax with notopleural depression silvery and pleurae with silvery patches. Palpi black, prominent and flat. Ocellar bristles small; two pairs of fronto orbital bristles; only one (outer) pair of vertical bristles. Frons slightly narrower in the male than in the female, but not with eyes almost touching). Four scutellar, no sternopleural, two postalar and one supra-alar bristles; (the anterior supra-alar bristle not present). Wings with upcurved discal cell (11) as in members of the Micropezidae. -

Notable Invertebrates Associated with Fens

Notable invertebrates associated with fens Molluscs (Mollusca) Vertigo moulinsiana BAP Priority RDB3 Vertigo angustior BAP Priority RDB1 Oxyloma sarsi RDB2 Spiders and allies (Arachnida:Araeae/Pseudoscorpiones) Clubiona rosserae BAP Priority RDB1 Dolomedes plantarius BAP Priority RDB1 Baryphyma gowerense RDBK Carorita paludosa RDB2 Centromerus semiater RDB2 Clubiona juvensis RDB2 Enoplognatha tecta RDB1 Hypsosinga heri RDB1 Neon valentulus RDB2 Pardosa paludicola RDB3 Robertus insignis RDB1 Zora armillata RDB3 Agraecina striata Nb Crustulina sticta Nb Diplocephalus protuberans Nb Donacochara speciosa Na Entelecara omissa Na Erigone welchi Na Gongylidiellum murcidum Nb Hygrolycosa rubrofasciata Na Hypomma fulvum Na Maro sublestus Nb Marpissa radiata Na Maso gallicus Na Myrmarachne formicaria Nb Notioscopus sarcinatus Nb Porrhomma oblitum Nb Saloca diceros Nb Sitticus caricis Nb Synageles venator Na Theridiosoma gemmosum Nb Woodlice (Isopoda) Trichoniscoides albidus Nb Stoneflies (Plecoptera) Nemoura dubitans pNotable Dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata ) Aeshna isosceles RDB 1 Lestes dryas RDB2 Libellula fulva RDB 3 Ceriagrion tenellum N Grasshoppers, crickets, earwigs & cockroaches (Orthoptera/Dermaptera/Dictyoptera) Stethophyma grossum BAP Priority RDB2 Now extinct on Fenland but re-introduction to undrained Fenland habitats is envisaged as part of the Species Recovery Plan. Gryllotalpa gryllotalpa BAP Priority RDB1 (May be extinct on Fenland sites, but was once common enough on Fenland to earn the local vernacular name of ‘Fen-cricket’.) -

Diptera) Diversity in a Patch of Costa Rican Cloud Forest: Why Inventory Is a Vital Science

Zootaxa 4402 (1): 053–090 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2018 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4402.1.3 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C2FAF702-664B-4E21-B4AE-404F85210A12 Remarkable fly (Diptera) diversity in a patch of Costa Rican cloud forest: Why inventory is a vital science ART BORKENT1, BRIAN V. BROWN2, PETER H. ADLER3, DALTON DE SOUZA AMORIM4, KEVIN BARBER5, DANIEL BICKEL6, STEPHANIE BOUCHER7, SCOTT E. BROOKS8, JOHN BURGER9, Z.L. BURINGTON10, RENATO S. CAPELLARI11, DANIEL N.R. COSTA12, JEFFREY M. CUMMING8, GREG CURLER13, CARL W. DICK14, J.H. EPLER15, ERIC FISHER16, STEPHEN D. GAIMARI17, JON GELHAUS18, DAVID A. GRIMALDI19, JOHN HASH20, MARTIN HAUSER17, HEIKKI HIPPA21, SERGIO IBÁÑEZ- BERNAL22, MATHIAS JASCHHOF23, ELENA P. KAMENEVA24, PETER H. KERR17, VALERY KORNEYEV24, CHESLAVO A. KORYTKOWSKI†, GIAR-ANN KUNG2, GUNNAR MIKALSEN KVIFTE25, OWEN LONSDALE26, STEPHEN A. MARSHALL27, WAYNE N. MATHIS28, VERNER MICHELSEN29, STEFAN NAGLIS30, ALLEN L. NORRBOM31, STEVEN PAIERO27, THOMAS PAPE32, ALESSANDRE PEREIRA- COLAVITE33, MARC POLLET34, SABRINA ROCHEFORT7, ALESSANDRA RUNG17, JUSTIN B. RUNYON35, JADE SAVAGE36, VERA C. SILVA37, BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR38, JEFFREY H. SKEVINGTON8, JOHN O. STIREMAN III10, JOHN SWANN39, PEKKA VILKAMAA40, TERRY WHEELER††, TERRY WHITWORTH41, MARIA WONG2, D. MONTY WOOD8, NORMAN WOODLEY42, TIFFANY YAU27, THOMAS J. ZAVORTINK43 & MANUEL A. ZUMBADO44 †—deceased. Formerly with the Universidad de Panama ††—deceased. Formerly at McGill University, Canada 1. Research Associate, Royal British Columbia Museum and the American Museum of Natural History, 691-8th Ave. SE, Salmon Arm, BC, V1E 2C2, Canada. Email: [email protected] 2.