<Xref Ref-Type="Transliteration" Rid="Trans1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Meccan Era in the Light of the Turkish Writings from the Prophet’S Birth Till the Rise of the Mission - I

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Vol 9 No 6 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Social Sciences November 2018 . Research Article © 2018 Noura Ahmed Hamed Al Harthy. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). The Meccan Era in the Light of the Turkish Writings from the Prophet’s Birth Till the Rise of the Mission - I Dr. Noura Ahmed Hamed Al Harthy Professor of Islamic History, Vice Dean of Scientific Research, University of Bishe, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Doi: 10.2478/mjss-2018-0163 Abstract The prophet’s biography had a supreme place in the Turkish writings. In this vein, the present research’s title is “The Meccan Era in the Turkish Writings from the prophet’s birth till the Prophetic Immigration to Medina”. Therefore in this research, a great amount of information about the Meccan era in the Turkish Writings from the prophet’s birth till the Prophetic Immigration to Medina was collected. It also included prophet’s life before and after the mission till the immigration to Abyssinia, the boycott, passing the second Aqaba Pledge, the Prophet's stand towards some contemporary nations and finally, the conclusion and the list of citied works and references. Before the prophet Muhammad Ibn Abd Allah's (PBUH) birth, the Arabian Peninsula lived in full darkness then it was enlightened by Islam. The prophet (PBUH) was not detached from the universal arena; rather, he was aware of the surrounding nations led by the Persians and Romans during that time. -

Islamic Civilization Experienced a Golden Age Under the Abbasid Dynasty, Which Ruled from the Mid 8Th Century Until the Mid 13Th Century

Included lands & peoples from parts of three continents (Europe, Africa, & Asia) Preserved, blended, & spread Greek, Roman, Indian, Persian & other civilizations. Enjoyed a prosperous golden age with advances in art, literature, mathematics, and science. Spread new learning to Christian Europe. A period of great prosperity or achievement, especially in the arts Islam began in the Arabian Peninsula in the early 7th century CE. It quickly spread throughout the Middle East before moving across North Africa, and into Spain and Sicily. By the 13th century, Islam had spread across India and Southeast Asia. The reasons for the success of Islam, and the expansion of its empire, can be attributed to the strength of the Arab armies, the use of a common language, and fair treatment of conquered peoples Arab armies were able to quickly conquer territory through the use of advanced tactics and the employment of horse and camel cavalry. Islamic rulers were very tolerant of conquered peoples, and welcomed conversion to the Islamic faith. All Muslims must learn Arabic, so they can read the Qur'an, the Islamic holy book. This common language helped to unite many different ethnic groups within the Islamic empire. It also made possible the easy exchange of knowledge and ideas. Islamic civilization experienced a golden age under the Abbasid Dynasty, which ruled from the mid 8th century until the mid 13th century. Under the Abbasids, Islamic culture became a blending of Arab, Persian, Egyptian, and European traditions. The result was an era of stunning -

Islam and Women's Literature in Europe

Islam and Women’s Literature in Europe Reading Leila Aboulela and Ingy Mubiayi Renata Pepicelli Contrary to the perception that Islam is against women and against the European way of life, some Muslim women based in Europe write novels and short stories in which Islam is described as instrument of empowerment in the life of their female characters. No more or not only an element of oppression, religion is portrayed as an element of a new identity for Muslim women who live in Europe. The Translator1 and Minaret2 by Leila Aboulela (Sudan/United Kingdom) and “Concorso”3 by Ingy Mubiayi (Egypt/Italy) are three works that demonstrate how the re-positioning of religion functions in women’s lives and struggles. I will first analyze the two novels written in English by Aboulela, followed by the short story written in Italian by Mubiayi. In The Translator (1999), Aboulela tells the story of Sammar, a young Sudanese woman who follewed her husband, a promising medical student, to Scotland. After her husband dies in a car accident, Sammar is alone in this foreign country. In Aberdeen she spends several painful and lonely years, far from her home and son who, after the terrible accident, lives in Khartoum with her aunt/mother-in-low. During this time, religion, day by day, becomes her only relief. Suddenly she finds work as an Arabic to English translator for an Islamic scholar, Rae, at a Scottish University, and she falls in love with him. Though her love is reciprocated, they have a problem. Rae is not Muslim, and for Sammar, Islam shapes and affects all aspects of life. -

Poverty and Economics in the Qur'an Author(S): Michael Bonner Source: the Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol

Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the editors of The Journal of Interdisciplinary History Poverty and Economics in the Qur'an Author(s): Michael Bonner Source: The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 35, No. 3, Poverty and Charity: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (Winter, 2005), pp. 391-406 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3657031 Accessed: 27-09-2016 11:29 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the editors of The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, The MIT Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Interdisciplinary History This content downloaded from 217.112.157.113 on Tue, 27 Sep 2016 11:29:33 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Journal of Interdisciplinary History, xxxv:3 (Winter, 2oo5), 39I-4o6. Michael Bonner Poverty and Economics in the Qur'an The Qur'an provides a blueprint for a new order in society, in which the poor will be treated more fairly than before. The questions that usually arise regarding this new order of society concern its historical con- text. Who were the poor mentioned in the Book, and who were their benefactors? What became of them? However, the answers to these apparently simple questions have proved elusive. -

Hostages and the Dangers of Cultural Contact: Two Cases from Umayyad Cordoba*

MARIBEL FIERRO Hostages and the Dangers of Cultural Contact: Two Cases from Umayyad Cordoba* Hostages are captives of a peculiar sort. Rather than having been captured during war, they are in the hands of the enemy as free persons who have temporarily lost their freedom, either because they were given and kept as a pledge (for example, for the fulfilment of a treaty) or in order to act as a substitute for someone who has been taken prisoner1. The prisoner, usually an important person, can regain his or her freedom under certain conditions, usually by the payment of a ransom. When those conditions are fulfilled, the hostage is released. In the medieval period, the taking of hostages was linked to conquest, the establishment of treaties, and the submission of rebels. The Spanish word for »hostage« (rehén, pl. rehenes) derives from the Arabic root r.h.n (which produces, in Classical Arabic, rāhin, pl. rahāʾin)2, and this origin attests to the fact that the practice of taking hostages was widespread in medieval Iberia and more generally in the Mediterranean3. The Muslims had not, however, invented it4. We lack specific studies dealing with hostages in Islamic lands and the procedures related to their taking and release, as well as their life as hostages, in spite of the fact that medieval historical and, more generally, literary sources are full of references to this widespread, persistent, and accepted practice which had advantages for both par- * This paper was undertaken as part of the project »Knowledge, heresy and political culture in the Islamic West (second/eighth–ninth/fifteenth centuries) = KOHEPOCU«, F03049 Advanced Research Grant, European Research Council (2009–2014). -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-12703-6 — Authority and Identity in Medieval Islamic Historiography Mimi Hanaoka Copyright Information More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-12703-6 — Authority and Identity in Medieval Islamic Historiography Mimi Hanaoka Copyright information More Information 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York NY 10013 Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning, and research at the highest international levels of excellence. www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781107127036 © Mimi Hanaoka 2016 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2016 Printed in the United Kingdom by Clays, St Ives plc A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data Names: Hanaoka, Mimi, author. Title: Authority and identity in medieval Islamic historiography : Persian histories from the peripheries / Mimi Hanaoka. Description: New York : Cambridge University Press, 2016. | Series: Cambridge studies in Islamic civilization | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016013911 | ISBN 9781107127036 (Hardback) Subjects: LCSH: Iran–History–640-1256–Historiography. | Iran–History–1256-1500– Historiography. | Turkey–History–To 1453–Historiography. Classification: LCC DS288 .H36 2016 | DDC 955.0072–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016013911 ISBN 978-1-107-12703-6 Hardback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet Web sites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such Web sites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. -

University of Lo Ndo N Soas the Umayyad Caliphate 65-86

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SOAS THE UMAYYAD CALIPHATE 65-86/684-705 (A POLITICAL STUDY) by f Abd Al-Ameer 1 Abd Dixon Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philoso] August 1969 ProQuest Number: 10731674 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731674 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2. ABSTRACT This thesis is a political study of the Umayyad Caliphate during the reign of f Abd a I -M a lik ibn Marwan, 6 5 -8 6 /6 8 4 -7 0 5 . The first chapter deals with the po litical, social and religious background of ‘ Abd al-M alik, and relates this to his later policy on becoming caliph. Chapter II is devoted to the ‘ Alid opposition of the period, i.e . the revolt of al-Mukhtar ibn Abi ‘ Ubaid al-Thaqafi, and its nature, causes and consequences. The ‘ Asabiyya(tribal feuds), a dominant phenomenon of the Umayyad period, is examined in the third chapter. An attempt is made to throw light on its causes, and on the policies adopted by ‘ Abd al-M alik to contain it. -

Tafsīr Surah Al-Kafirun

Tafsīr Surah al-Kafirun By Haider Hobbollah Transcribed and translated by Syed Ali Imran (Canada) Names, Reasons of Revelation The chapter has been referred to in three ways in Islamic works: 1. Surah al-Kāfirūn 2. Surah al-Juḥd – since Juḥd means rejection, this name was probably given due to the rejection that appears in the later verses 3. Surah al-Muqashqisha – some have called both this and Surah Ikhlās together as al-Muqashqishatān. Qashqasha means to sweep away and abandon something, and the chapter is given this name because of the rejection (barā’ah) mentioned in the verses. A group of disbelievers in Makkah, including al-Ḥārith b. Qays al-Sahmī, al-‘Āṣ b. Wā’il, al-Walīd b. Mughīrah, Umayyah b. Khalaf and others, came to the Prophet (p) and said to him, why do you not worship what we worship, and we will worship what you worship for a time period, after which we will see whose god and worship is better, who sees the results of their worship soon after. If your god and worship are better then that will be a moment of pride for the Quraysh and we will take a share of it, but if you (p) find that our gods and worship are better then you shall take a share of it. As per historical reports, the Prophet (p) rejected their offer. This chapter was revealed and the Prophet (p) left the Masjid al-Ḥarām and recited it in front of the people. This is the popular report describing the reasons for the chapter’s revelation, both in Sunnī and Shī’ī texts, the latter works including traditions from the Ahl al-Bayt (a) as well. -

What Is (Un)Islamic About Islamic Politics?

What is (un)Islamic about Islamic Politics? Copyright 2003 Nelly Lahoud Introduction Islamists believe that their political ideology and activismare Islamic.1 [1] Islamic politics carries the sense that there is an Islamic way of going about applying Islam to political affairs, and that this way is morally and politically superior to other forms of rule because it is a divinely inspired system. This paper questions the claimed authenticity and absence of ambiguity in such claims. It argues that there is more to the term �Islamic' than those properties claimed by the proponents of this idea. It probes certain hermeneutic and religio‐historical assumptions in the Islamic tradition, following two different and (roughly) independent aspects: the first questions conventional assumptions about Scripture and the assumed links between Scripture, authority and Islamic authenticity. The second accepts conventional beliefs and shows that even from this angle, there does not exist a consensus or a uniform position on how to go about Islamic political rule. In probing what is conventionally assumed to be �Islamic' in relation to political rule, it is not intended to deny the significance of the �Islamic' category in �Islamic politics' or for that matter 1 [1] The Islamists are the proponents of Islamism, a political current that attributes ideological dimension to the religion of Islam. It has claimed a monopoly over Islam by professing to be faithful to God's revealed law in the Qur'an and His messenger Muhammad's teachings as illustrated in the Hadith. to create/impose yet another arbitrary category in its place. Rather, the purpose is to open a space within which one is able to question and debate the various conventional divisions and qualifiers. -

Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : the Role of Al-Azhar, Al-Medina and Al-Mustafa Masooda Bano Editor

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eCommons@AKU eCommons@AKU Exploring Muslim Contexts ISMC Series 3-2015 Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Masooda Bano Editor Keiko Sakurai Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_emc Recommended Citation Bano, M. , Sakurai, K. (Eds.). (2015). Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Vol. 7, p. 242. Available at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_emc/9 Shaping Global Islamic Discourses Exploring Muslim Contexts Series Editor: Farouk Topan Books in the series include Development Models in Muslim Contexts: Chinese, “Islamic” and Neo-liberal Alternatives Edited by Robert Springborg The Challenge of Pluralism: Paradigms from Muslim Contexts Edited by Abdou Filali-Ansary and Sikeena Karmali Ahmed Ethnographies of Islam: Ritual Performances and Everyday Practices Edited by Badouin Dupret, Thomas Pierret, Paulo Pinto and Kathryn Spellman-Poots Cosmopolitanisms in Muslim Contexts: Perspectives from the Past Edited by Derryl MacLean and Sikeena Karmali Ahmed Genealogy and Knowledge in Muslim Societies: Understanding the Past Edited by Sarah Bowen Savant and Helena de Felipe Contemporary Islamic Law in Indonesia: Shariah and Legal Pluralism Arskal Salim Shaping Global Islamic Discourses: The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Edited by Masooda Bano and Keiko Sakurai www.euppublishing.com/series/ecmc -

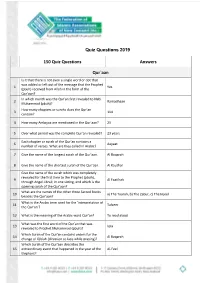

Quiz Questions 2019

Quiz Questions 2019 150 Quiz Questions Answers Qur`aan Is it that there is not even a single word or dot that was added or left out of the message that the Prophet 1 Yes (pbuh) received from Allah in the form of the Qur’aan? In which month was the Qur’an first revealed to Nabi 2 Ramadhaan Muhammad (pbuh)? How many chapters or surahs does the Qur’an 3 114 contain? 4 How many Ambiyaa are mentioned in the Qur’aan? 25 5 Over what period was the complete Qur’an revealed? 23 years Each chapter or surah of the Qur’an contains a 6 Aayaat number of verses. What are they called in Arabic? 7 Give the name of the longest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Baqarah 8 Give the name of the shortest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Kauthar Give the name of the surah which was completely revealed for the first time to the Prophet (pbuh), 9 Al Faatihah through Angel Jibrail, in one sitting, and which is the opening surah of the Qur’aan? What are the names of the other three Sacred Books 10 a) The Taurah, b) The Zabur, c) The Injeel besides the Qur’aan? What is the Arabic term used for the ‘interpretation of 11 Tafseer the Qur’an’? 12 What is the meaning of the Arabic word Qur’an? To read aloud What was the first word of the Qur’an that was 13 Iqra revealed to Prophet Muhammad (pbuh)? Which Surah of the Qur’an contains orders for the 14 Al Baqarah change of Qiblah (direction to face while praying)? Which Surah of the Qur’aan describes the 15 extraordinary event that happened in the year of the Al-Feel Elephant? 16 Which surah of the Qur’aan is named after a woman? Maryam -

Controversies Over Islamic Origins

Controversies over Islamic Origins Controversies over Islamic Origins An Introduction to Traditionalism and Revisionism Mun'im Sirry Controversies over Islamic Origins: An Introduction to Traditionalism and Revisionism By Mun'im Sirry This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Mun'im Sirry All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6821-0 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6821-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................................... vii Introduction: Celebrating the Diversity of Perspectives ............................ ix Chapter One ................................................................................................ 1 The Problem of Sources as a Source of Problems Sources of the Problem ......................................................................... 5 Towards a Typology of Modern Approaches ..................................... 20 Traditionalist and Revisionist Scholarship .......................................... 37 Faith and History ...............................................................................