Towards an Understanding of the Economy of Johannesburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Annual Report March 2020

INTEGRATED 21020 2020 ANNUAL REPORT SOUTH AFRICA Integrated annual report and annual nancial statements Investec Property Fund Limited Investec Property Fund Limited integrated annual report and nancial statements integrated Property Fund Property Fund Limited GLOSSARY OF TERMS AGM Annual General Meeting AREG L.P AREG Hexagon Co-Invest Vehicle II, LP ASX Australian Securities Exchange AUD Australian Dollar B-BBEE Broad-based black economic empowerment Board Board of directors of IPF CCS Cross-currency swap CGT Capital gains tax CPS Cents per share CSI Corporate social investment DMTN Domestic medium term note Euribor The Euro Interbank offered rate Edcon Edcon Acquisition Proprietary Limited EDT Entrepreneurship Development Trust ERV Expected rental value EUR Euro EV Enterprise value EY Ernst & Young Inc. FECs Forward exchange contracts FVTPL Fair value through profit or loss GAV Gross asset value GBF General banking facility GBP Great British Pound GLA Gross lettable area Group revenue or gross income Revenue from all investments and aggregated on a proportionally consolidated basis Group NOI Group net operating income Hexagon Hexagon Holdco S.a.r.l and Hexagon Holdco S.a.r.l 2 HFS Held for sale HQLA High quality liquid assets IAP Investec Australia Property Fund ICR Interest coverage ratio IPFO Investec Property Fund Offshore Investments Proprietary Limited IFRS International Financial Reporting Standards IRS Interest rate swaps Investec Investec Bank Limited Investec Property or The Manager Investec Property Proprietary Limited IPF -

20201101-Gp-Advert Rand West City Sheriff Service Area.Pdf

RRaanndd WWeesstt CCiittyy SShheerriiffff SSeerrvviiccee AArreeaa !. ELANDSFONTEIN GOLDEN VALLEY MALONY'S EYE Wallis Haven SP DELAREY Hillside AH Oaktree AH Muldersdrift AH VAN WYK'S^MULDERSDRIF Rietfontein AH Cosmo City Noordhang Jukskei Douglasdale Petervale KOESTERSFONTEIN Protea HONINGKLIP Park Molote SP WELTEVREDEN Delarey RESTANT Sonnedal AH DOUGLASDALE R511 HARTEBEESTFONTEIN Reydal AH Ridge AH MULDERSDRIFT North Riding WITKOPPEN ST ZUIKERBOSCHFONTEIN DELAREY REYDAL RIETFONTEIN ZANDSPRUIT North AH VLAKDRIFT N14 SAPS Jackal MIGALSOORD Heuningklip AH K Riding AH L Rietvei AH STERKFONTEIN KRUGERSDORP RIETVALLEI N14 UHLENHORST Creek Golf Bellairs Park RANDBURG Mogale ZUMICK LK Estate MAGALIESBURG STR24 SAPS RIETVALLEI OLIEVENHOUTPOORT Olivedale Bryanston BRYANSTON VLAKFONTEIN City NU DELAREY R28 Rietfontein AH WILGESPRUIT SAPS SAPS Sterkfontein R563 Rant-en-Dal ST Northgate RIETFONTEIN PLATKLIP KAALFONTEIN TARLTON ST Homes Haven Ruimsig Zonnehoewe AH R512 Country WOLVEKRANS Bagale Marabeth HONEYDEW ST Beverley Gardens WELTEVREDEN Beckedan AH WATERVAL Sundowner SAPS AH Rustenburg NU Noord Tres Jolie AH Las^er Northworld Ferndale Bryanbrink Life Park OUDRIF Dan Pienaarville RUIMSIG ^ Wolwekrans GREENWAY Featherbrooke River Club Eljeesee Delporton Alsef AH Park ñ Bromhof BOONS AH Quellerie Park Estate Ruimsig Ruimsig Kensington B SAPS AH STR28 Noordheuwel AH RANDBURG R512 Moodie Hill WELTEVREDEN Vlakplaas AH Eldorado Waterval AH ñ GRENS Helderblom Krugersdorp Eagle Boskruin ST Hurlingham Rangeview Poortview Willowbrook Harveston KN1 KLIPFONTEIN Parkmore BRICKVALE KRUGERSDORP Canyon L VLAKPLAATS AH AH Oatlands Apple AH BOSCHKOP MOADOWNS Game Reserve AH Ambot AH Bordeaux ZANDFONTEIN WITSTINKHOUTBOOM ^KRUGERSDORP AH Ruiterhof Park Amorosa Randpark RANDPARK Glenadrienne SP1 WATERVAL Krugersdorp Kenmare Roodekrans Honeydew Ridge Moret R24 Radiokop HOUTKOP GROENPLAATS ST Boltonia PAARDEPLAATS HORISON Ridge Central ROODEKRANS Wilgeheuwel Randpark Blairgowrie Craighall Randfontein WILGESPRUIT R512 Sandhurst NNOORRTTHH WWEESSTT AVALON !. -

2020/21 Integrated Development Plan Review

2020/21 INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN REVIEW 2 An agile and resilient metropolitan government that is people centred 2020/21 INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN REVIEW Our commitment The City of Johannesburg; in the interest of impacting positively on the city and the lives of all who live in it, commits itself to: Adding value by being action-oriented in our engagements; being better informed; responding to the city’s challenges in a visible and proactive manner Being committed civil servants, ready to serve the people of Joburg through sustainable, high- impact interventions that lead to accelerated economic growth for the city and the country (serving as “change makers”/ disrupters”) Ensuring we maintain the future focus of the National Development Plan (NDP), Growing Gauteng Together (GGT) 2030, and the Joburg 2040 Growth and Development Strategy ( GDS) at the core of all we do – delivering with professionalism, customer centricity, effective internal decision making, alignment with King IV principles, and a focus on supporting economic activity and using modern communication channels to improve accountability to communities Being productive – contributing to a productive City Ensuring synergised service delivery with authentic impact – countering a context of a trust deficit, service delivery breakdowns, incoherent links across the City, delivery on a ‘just in time’ principle, a lack of standardisation of how we operate, and inconsistent outcomes inspirational human capital management – focusing on improving staff morale, efficient service -

Medicines and Related Substances Act, 1965 (Act 101 of 1965)

STAATSKOERANT, 27 SEPTEMBER 2013 No. 36879 3 GENERAL NOTICE ALGEMENE KENNISGEWING NOTICE 963 OF 2013 MEDICINES CONTROL COUNCIL CONDITIONS OF REGISTRATION OF A MEDICINE IN TERMS OF THE PROVISIONS OF SECTION 15(7) OF THE MEDICINES AND RELATED SUBSTANCES ACT, 1965 (ACT 101 OF 1965) 1. The applicant shall ensure that the medicine is manufactured and controlled in terms of the current Good Manufacturing Practices as determined by Council 2. The manufacture of this medicine is subject to regular investigation and inspections by the inspectors appointed in terms of Section 26 of the Act, to assess compliance with current Good Manufacturing Practices. 3. The information in the package insert shall be updated on a regular basis to conform to the package insert recently approved by Council. 4. The applicant must comply with all the legal requirements of the Medicines and Related Substances Act, 1965 (Act 101 of 1965). 5. The registration of this medicine shall be subject to review at intervals as determined by Council regardingitsquality, safety and efficacy, and the registration of this medicine may be varied subject to issues Council may deem fit. 6. The first two production batches must be fully validated in terms of the detailed process validation protocol submitted at the time of application for registration, and the validation report must be submitted within a month after completion of the validation. 7. The product may be advertised to the professions only. 8. The provisional shelf-life allocated must be confirmed with stability data over the full shelf-life period on the first two production batches (well-known API) or first three production batches (NCE) in accordance with the Stability Guideline. -

Going Beyond the BIDVEST GROUP LIMITED BROCHURE 2017 PRODUCTS and SERVICES

THE BIDVEST GROUP LIMITED PRODUCTS AND SERVICES BROCHURE 2017 THE BIDVEST GROUP LIMITED PRODUCTS AND SERVICES Going Beyond THE BIDVEST GROUP LIMITED PRODUCTS AND SERVICES BROCHURE 2017 Welcome to a year of going beyond Bidvest is a leading South African services, trading and distribution group operating in the areas of consumer and industrial products, electrical products, financial services, fishing and materials handling, freight management, office and print solutions, outsourced hard and soft services, travel and aviation services and automotive retailing. Listed on the JSE Limited and with roots firmly established in South Africa, we consistently broaden our product offering through organic and acquisitive growth in local as well as select niche international markets. We unbundled our foodservice operations and separately listed Bid Corporation Limited (Bidcorp) on the JSE on May 30 2016. The successful and value enhancing unbundling has allowed our management team to move forward with a refocused platform from which to pursue growth. As a group, we will benefit from a greater visibility of our continued operations, and their potential values. Entrepreneurship, incentivisation, decentralised management and communication are the keys. We turn ordinary companies into extraordinary performers, delivering strong and consistent shareholder returns in the process. Most importantly, we understand that people create wealth, and that companies only report it. www.bidvest.com Contents WE ARE BIDVEST IFC Bidvest at a glance 02 DIVISIONAL OVERVIEW 04 Bidvest Automotive 06 Bidvest Commercial Products 08 Bidvest Electrical 12 Bidvest Financial Services 14 Bidvest Freight 16 Bidvest Office and Print 18 Bidvest Services 20 Bidvest Namibia 22 Bidvest International 24 TRANSFORMATION AND CSI 26 Transformation 28 CSI 32 ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION 38 Bidvest directory 40 Administration 64 While we employ more than 117 000 people, we run our company with the determination and commitment evident in a small business heart. -

SAARF OHMS 2006 Database Layout

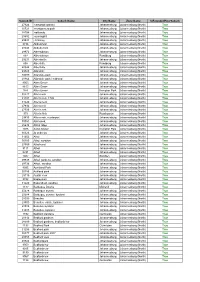

SAARF OUTDOOR MEASUREMENT SURVEY PRIVATE & CONFIDENTIAL Outdoor Database Layout South Africa (GAUTENG & KWAZULU-NATAL) August 2007 FILES FOR COMPUTER BUREAUX Prepared for: - South African Advertising Research Foundation (SAARF) Prepared by: - Nielsen Media Research and Nielsen Outdoor Copyright Reserved Confidential 1 The following document describes the content of the database files supplied to the computer bureaux. The database includes four input files necessary for the Outdoor Reach and Frequency algorithms: 1. Outdoor site locations file (2 – 3PPExtracts_Sites) 2. Respondent file (2 – 3PPExtracts_Respondents) 3. Board Exposures file (2 – Boards Exposure file) 4. Smoothed Board Impressions file (2 – Smoothed Board Impressions File) The data files are provided in a tab separated format, where all files are Window zipped. 1) Outdoor Site Locations File Format: The file contains the following data fields with the associated data types and formats: Data Field Max Data type Data definitions Extra Comments length (where necessary) Media Owner 20 character For SA only 3 owners: Clear Channel, Outdoor Network, Primedia Nielsen Outdoor 6 integer Up to a 6-digit unique identifier for Panel ID each panel Site type 20 character 14 types. (refer to last page for types) Site Size 10 character 30 size types (refer to last pages for sizes) Illumination hours 2 integer 12 (no external illumination) 24 (sun or artificially lit at all times) Direction facing 2 Character N, S, E, W, NE, NW, SE, SW Province 25 character 2 Provinces – Gauteng , Kwazulu- -

Historical Land Planning, Transport Poverty and Sustainable Cities: the Case of Johannesburg

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za (Accessed: Date). Historical land planning, transport poverty and sustainable cities: the case of Johannesburg Dr Michelle Claire Lawton Department of Geography, Environmental Management and Energy Studies Faculty of Science University of Johannesburg Mini-dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree Masters of Science in Environmental Management Supervisor: Mrs Tracey J. McKay Co-Supervisor: Dr June Meeuwis December 2014 ANTI-PLAGIARISM DECLARATION University of Johannesburg Department of Geography, Environmental Management & Energy Studies Title: Dr Full name: Michelle Claire Lawton Student number: 909906451 Course: Mini dissertation MSc in Environmental Management 1. I understand what plagiarism is and am aware of the University’s policy in this regard. 2. I know that plagiarism is wrong. Plagiarism is to present someone else’s ideas as my own. I know that I would plagiarise if I do not give credit to my sources, or if I lift sentences or paragraphs from a book, article or internet source without proper citation. -

Netflorist Designated Area List.Pdf

Subrub ID Suburb Name City Name Zone Name IsExtendedHourSuburb 27924 carswald kyalami Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30721 montgomery park Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28704 oaklands Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28982 sunninghill Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29534 • bramley Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 8736 Abbotsford Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28048 Abbotts ford Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29972 Albertskroon Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 897 Albertskroon Randburg Johannesburg (North) True 29231 Albertsville Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 898 Albertville Randburg Johannesburg (North) True 28324 Albertville Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29828 Allandale Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30099 Allandale park Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28364 Allandale park / midrand Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 9053 Allen Grove Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 8613 Allen Grove Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 974 Allen Grove Kempton Park Johannesburg (North) True 30227 Allen neck Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 31191 Allen’s nek, 1709 Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 31224 Allens neck Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 27934 Allens nek Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 27935 Allen's nek Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 975 Allen's Nek Roodepoort Johannesburg (North) True 29435 Allens nek, rooderport Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30051 Allensnek, Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28638 -

Gauteng Johannesburg Main Seat of Johannesburg Central Magisterial

# # !C # # # ## ^ !C# !.!C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C# # # # # # !C # ^ # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # !C # # !C # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # ## # !C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # #!C # !C # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # ^ # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # ##^ !C # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # ## # # # #!C # !C# # # ##!C # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C !C # # # # # # # # !C # # #!C # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # ### !C # # !C # # # # !C # ## ## ## !C # # !C # !. # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # ### # # # # # # # # # # !C ## # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # !C !C### # # # ## # !C # # # # # !C# # # # # # # !C # # # # !C # ^ # # # !C # ^ # # ## !C # # # !C #!C ## # # # # # # ## # # # # # ## # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # -

Industrial Nodes: Bringing Jobs Closer to People in Townships?

SUPPORT TOWNSHIP ECONOMIES SERIES #3 PROGRAMME What are Industrial Nodes? Nancefeld Industrial Nodes are areas that are zoned for industrial and light manufacturing activity, intended to enable efcient and efective delivery of core services required for business Industrial nodes: – in the process, enhancing their scope for growth. Over the years, many such hubs have been developed – some dating back bringing jobs closer to several decades. In Gauteng, the Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development (CCRED) surveyed 26 such nodes. people in townships? Within Industrial Nodes, there is an expectation that ‘agglomeration Under apartheid, townships were This edition of the Township Economy efects’ will enhance productivity, designed to exist at a distance Series of the Cities Support Programme due to the greater efciencies from economic opportunities, explores these questions, with a focus and economies of scale that arise as dormitory towns for labour. on case studies of Industrial Nodes when many frms operate in As a result, transport costs as adjacent to townships in Gauteng, in close proximity to each other. So, well as the time spent traveling particular, Aeroton, Nancefeld, and for example, such proximity – or add economic and social costs to Devland – all of which are close to agglomeration – of frms is expected the cost of labour: with both these Soweto, Eldorado Park and Orange to create efciencies in the delivery of public costs reducing aggregate productivity. Farm. services such as electricity, water and public ome strategies to address transport. In the process, such hubs also this focus on improved, more create economies of scale for support frms in afordable transport linkages. -

Gauteng Soweto Sub District of Johannesburg Central Magisterial

# # !C # # # # # ^ !C # !.!C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C# # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # # !C # #^ # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # ^ # # !C # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # #!C # # # # # # !C# # ##!C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # !C # #!C # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ### # !C # # !C # # # # !C # # ## ## !C # # !C !. # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # ^ # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # !C !C## ## # # # # # !C # # # # !C# # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # ^ # # # !C # ^ # # !C # # # # !C #!C ## # # # # # # # # # ## # # # ## # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # #