Trust Trail: Scientific York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Walls but on the Rampart Underneath and the Ditch Surrounding Them

A walk through 1,900 years of history The Bar Walls of York are the finest and most complete of any town in England. There are five main “bars” (big gateways), one postern (a small gateway) one Victorian gateway, and 45 towers. At two miles (3.4 kilometres), they are also the longest town walls in the country. Allow two hours to walk around the entire circuit. In medieval times the defence of the city relied not just on the walls but on the rampart underneath and the ditch surrounding them. The ditch, which has been filled in almost everywhere, was once 60 feet (18.3m) wide and 10 feet (3m) deep! The Walls are generally 13 feet (4m) high and 6 feet (1.8m) wide. The rampart on which they stand is up to 30 feet high (9m) and 100 feet (30m) wide and conceals the earlier defences built by Romans, Vikings and Normans. The Roman defences The Normans In AD71 the Roman 9th Legion arrived at the strategic spot where It took William The Conqueror two years to move north after his the rivers Ouse and Foss met. They quickly set about building a victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. In 1068 anti-Norman sound set of defences, as the local tribe –the Brigantes – were not sentiment in the north was gathering steam around York. very friendly. However, when William marched north to quell the potential for rebellion his advance caused such alarm that he entered the city The first defences were simple: a ditch, an embankment made of unopposed. -

Micklegate Soap Box Run Sunday Evening 26Th August and All Day Bank Holiday Monday 27Th August 2018 Diversions to Bus Services

Micklegate Soap Box Run Sunday evening 26th August and all day Bank Holiday Monday 27th August 2018 Diversions to bus services Bank Holiday Monday 27th August is the third annual Micklegate Run soap box event, in the heart of York city centre. Micklegate, Bridge Street, Ouse Bridge and Low Ousegate will all be closed for the event, with no access through these roads or Rougier Street or Skeldergate. Our buses will divert: -on the evening of Sunday 26th August during set up for the event. -all day on Bank Holiday Monday 27th August while the event takes place. Diversions will be as follows. Delays are likely on all services (including those running normal route) due to increased traffic around the closed roads. Roads will close at 18:10 on Sunday 26th, any bus which will not make it through the closure in time will divert, this includes buses which will need to start the diversion prior to 18:10. Route 1 Wigginton – Chapelfields – will be able to follow its normal route throughout. Route 2 Rawcliffe Bar Park & Ride – will be able to follow its normal route throughout. Route 3 Askham Bar Park & Ride – Sunday 26th August: will follow its normal route up to and including the 18:05 departure from Tower Street back to Askham Bar Park & Ride. The additional Summer late night Shakespeare Theatre buses will then divert as follows: From Askham Bar Park & Ride, normal route to Blossom Street, then right onto Nunnery Lane (not serving the Rail Station into town), left Bishopgate Street, over Skeldergate Bridge to Tower Street as normal. -

Reducing the Risk of Flooding

reducing the risk of flooding A guide to our flood defence schemes in York x73694_EA_p10_sb.indd 1 10/3/09 08:31:28 We are the Environment Agency. It’s our job to look after your environment and make it a better place – for you, and for future generations. Your environment is the air you breathe, the water you drink and the ground you walk on. Published by: Environment Agency Rivers House 21 Park Square South Leeds LS1 2QG Tel: 08708 506 506 Email: [email protected] www.environment-agency.gov.uk February 2009 © Environment Agency All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. x73694_EA_p8_vw.indd 2 24/2/09 16:33:09 Flooding is a natural occurrence. we can’t always stop flooding but we can help to prevent it. We aim to reduce the risk of flooding by managing land, rivers, coastal systems and flood defences. While we do everything we can to reduce the chance of flooding, it is a natural process and can never be completely eliminated. Environment Agency Protecting York from flooding 1 x73694_EA_p9_sb.indd 1 5/3/09 18:11:21 reducing the risk During a flood, we issue flood warnings. We also control our systems such as flood gates and barriers What is the ‘normal’ and we clear obstructions that may cause hazards. level of water in York? The normal water level (sometimes We use the latest technology to monitor river levels, rainfall, tides and sea called the normal summer water conditions, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. -

Lendal Bridge Trial – Month One (September 2013) Data Release

Lendal Bridge Trial – Month One (September 2013) Data Release Foreword: The Lendal Bridge trial is a bold experiment to tackle city centre congestion, a problem which continues to impact on residents, businesses and visitors. The aim of the trial is to reduce the volume of traffic in the corridor between the rail station and St Leonard‟s place, enabling improvements to bus services, creating a more pleasant environment for pedestrians and cyclists, thereby attracting people into the city. In the longer term this will underpin the city centre commercial and retail economies. The assessment of the success, or otherwise, of the trial will be based on the evaluation of a wide range of data Evaluation: The Council (CYC) has appointed ITS to undertake independent evaluation of the Lendal Bridge trial. The success, or otherwise, of the trial is based on a number of Evaluation Criteria, broadly based on CYC‟s five priorities to: Create jobs and grow the economy, Get York moving, Build strong communities, Protect vulnerable people, and Protect the environment. The lead indicators are those where it might be expected to see a change (either positive or negative) during the trial period. Please note that not all of the evaluation data this is available at this early stage of the trial. Summary of Observations: Overall the traffic network has responded well to the restriction, with preliminary results from automatic counters indicating decreases in traffic volumes on some key routes against increases on others. Preliminary results from automatic traffic counters indicate increases in traffic on Foss Islands Road and Clifton Bridge, with Leeman Road and the A1237 experiencing a small decrease in traffic volumes. -

Creating the Slum: Representations of Poverty in the Hungate and Walmgate Districts of York, 1875-1914

Laura Harrison Ex Historia 61 Laura Harrison1 University of Leeds Creating the slum: representations of poverty in the Hungate and Walmgate districts of York, 1875-1914 In his first social survey of York, B. Seebohm Rowntree described the Walmgate and Hungate areas as ‘the largest poor district in the city’ comprising ‘some typical slum areas’.2 The York Medical Officer of Health condemned the small and fetid yards and alleyways that branched off the main Walmgate thoroughfare in his 1914 report, noting that ‘there are no amenities; it is an absolute slum’.3 Newspapers regularly denounced the behaviour of the area’s residents; reporting on notorious individuals and particular neighbourhoods, and in an 1892 report to the Watch Committee the Chief Constable put the case for more police officers on the account of Walmgate becoming increasingly ‘difficult to manage’.4 James Cave recalled when he was a child the police would only enter Hungate ‘in twos and threes’.5 The Hungate and Walmgate districts were the focus of social surveys and reports, they featured in complaints by sanitary inspectors and the police, and residents were prominent in court and newspaper reports. The area was repeatedly characterised as a slum, and its inhabitants as existing on the edge of acceptable living conditions and behaviour. Condemned as sanitary abominations, observers made explicit connections between the physical condition of these spaces and the moral behaviour of their 1 Laura ([email protected]) is a doctoral candidate at the University of Leeds, and recently submitted her thesis ‘Negotiating the meanings of space: leisure, courtship and the young working class of York, c.1880-1920’. -

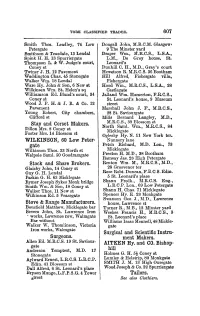

Stay and Corset Makers. WILKINSON, 60 Low Peter- Gate Stock And

YORK CLASSIFIED TRADES. 607 Smith Thos. Leadley, 74 Low Dougall John, M.B.C.M. Glasgow' Petergate 9 The Minster yard Smithson & Teasdale, 13 Lendal Draper Wm., M.R.C.S., L.S.A., Spink H. H. 13 Spurriergate L.M., De Grey house, St. Thompson L. & W, Judge's court, Leonard's Coney st Dunhill C. H., M.D., Gray's court Twiner J. H. 12 Pavement Hewetson R M.RC.S. 36 Bootham Waddington Chas. 45 Stonegate Hill Alfred, Fishergate villa, Walker Wm. 18 Lendal Fishergate Ware Hy. John & Son, 6 New st Hood Wm., M.R.C.S., L.S.A., 28 Wilkinsen Wm. St. Helen's sq Castlegate Williamson Ed. Bland's court, 34 Jalland Wm. Hamerton, F.R.C.S., Coney st St. Leonard's house, 9 Museum Wood J. P. H. & J. R. & Co. 12 street Pavement Marshall John J. F., M.R.C.S., Young Robert, City chambers, 28 St. Saviourgate Clifford st Mills Bernard Langley, M.D., M.RO.S., 39 Blossom st Stay and Corset Makers. North Sam!. Wm., M.R.C.S., 84 Dillon Mrs. 8 Coney st Micklegate Foster Mrs. 14 Blossom st Oglesby Hy. N. 11 New York ter. WILKINSON, 60 Low Peter- Nunnery lane gate Petch Richard, M.D. Lon., 73 Wilkinson Thos. 33 North st Micklegate Walpole Sam!. 50 Goodramgate Preston H. M.D., 38 Bootham Ramsay Jas. 23 High Petergate Stock and Share Brokers. Renton Wm. M., M.R.C.S., M.D., Glaisby John, 14 Coney st 28 Grosvenor ter Guy G. H. Lendal Rose Robt. -

MINT YARD York Conservation Management Plan

MINT YARD York Conservation Management Plan FINAL DRAFT Simpson & Brown Architects With Addyman Archaeology August 2012 Contents Page 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 2.0 INTRODUCTION 11 2.1 Objectives of the Conservation Plan ...............................................................................11 2.2 Study Area ..........................................................................................................................11 2.3 Heritage Designations.......................................................................................................13 2.4 Structure of the Report......................................................................................................14 2.5 Adoption & Review...........................................................................................................15 2.6 Other Studies......................................................................................................................15 2.7 Limitations..........................................................................................................................15 2.8 Orientation..........................................................................................................................15 2.9 Project Team .......................................................................................................................15 2.10 Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................16 2.11 Abbreviations and Definitions.........................................................................................16 -

John Carr of York 1723 – 1807 Bruce Speed November 2019

The Life and Work of John Carr of York 1723 – 1807 Bruce Speed November 2019 John Carr by William Beechey 1791 HAREWOOD Garden Front as modified by Sir Charles Barry The iconic Henry Flitcroft frontage of WENTWORTH WOODHOUSE. Carr took over and completed the project, designing the Stables and Riding School, lodges, the Rockingham Mausoleum and Keppel’s Column over 50 years. THE CRESCENT, BUXTON, Carr’s favourite, the drawings for which his hand rests on his portrait CROFT BRIDGE, RIVER TEES, 1795, one many designed by Carr. Carr’s Birthplace near Wakefield Huthwaite Hall, Thurgoland 1748, Carr’s first Photograph by Stephen Richards for use under Creative Commons Licence Huthwaite Hall, Thurgoland, as it is today FARNLEY HALL, CARR’S GEORGIAN ADDITION TO JACOBEAN MANSION FARNLEY HALL Group visit in April 2019 Kirby Hall, Little Ouseburn designed by Roger Morris and the Earl of Burlington, gave Carr project management experience, 1748 -55 Photo from The Life and Works of John Carr of York by Brian Wragg. Enclosure of the Pikeing Well was Carr’s first project for the City of York. ALBION STREET, SKELDERGATE, the site of Carr’s Garden. The house was demolished in the 1940’s KNAVESMIRE STANDHOUSE. Carr’s design won against strong competition with the support of the Marquis of Rockingham, leading to long involvement with the family. 2ND MARQUIS OF ROCKINGHAM After Joshua Reynolds WENTWORTH WOODHOUSE THE BARAOQUE MANSION OF 1725 WENTWORTH WOODHOUSE HAREWOOD Garden Front of Carr’s most important Yorkshire house HAREWOOD NEWBY HALL, Carr turned the building making the east front the entrance and added the wing for the gallery. -

19-02672-FULM Northern House Presentation

Planning Committee To be held remotely on 24th February 2021 at 4:30pm City of York Council Planning Committee Meeting - 24th February 2021 1 19/02672/FULM - Northern House, Rougier Street, York Demolition of 1 - 9 Rougier Street and erection of 10 storey building, with roof terraces, consisting of mixed use development including 211 apartments (Use Class C3), offices (Use Class B1), visitor attraction (Use Class D1), with associated landscaping and public realm improvements City of York Council Planning Committee Meeting - 24th February 2021 2 Location Plan City of York Council Planning Committee Meeting - 24th February 2021 3 Existing View from City Walls City of York Council Planning Committee Meeting - 24th February 2021 4 Existing View – Rougier Street City of York Council Planning Committee Meeting - 24th February 2021 5 Existing View – Rougier Street North West End City of York Council Planning Committee Meeting - 24th February 2021 6 Existing View – Tanner’s Moat from City Walls City of York Council Planning Committee Meeting - 24th February 2021 7 Existing View – View of All Saints from Station Road/City Walls City of York Council Planning Committee Meeting - 24th February 2021 8 Existing View from Lendal Tower City of York Council Planning Committee Meeting - 24th February 2021 9 Existing View from Museum Street City of York Council Planning Committee Meeting - 24th February 2021 10 Existing View from City Screen City of York Council Planning Committee Meeting - 24th February 2021 11 Existing View from North Street City of York -

Traditional Butchers

FOR SALE TRADITIONAL BUTCHERS 19 LENDAL, YORK, YO1 8AQ ESTABLISHED FOOD BASED BUSINESS WITH EXCELLENT REPUTATION SUITABLE FOR AN OWNER OCCUPIER OR ESTABLISHED OPERATION CITY CENTRE LOCATION BENEFITTING FROM HIGH LEVELS OF FOOTFALL FULLY EQUIPPED UNIT WITH A NET INTERNAL AREA OF 26.84 SQ.M (289 SQ.FT) BUSINESS FOR SALE - £49,500 LEASE, GOODWILL AND FIXTURES & FITTINGS VIEWING: STRICTLY BY APPOINTMENT WITH THE SOLE SELLING AGENTS 20 CASTLEGATE, YORK, YO1 9RP TEL: 01904 659990 FAX: 01904 612910 E-MAIL : [email protected] WEB: WWW.BARRYCRUX.CO.UK Barry Crux & Company Limited Registered Office: 20 Castlegate, York, YO1 9RP Registered in England No. 7198539 VAT Reg No. 500 9839 50 Barry Crux & Company is the trading name of Barry Crux & Company Limited. DESCRIPTION FIXTURES & FITTINGS The business is situated in an attractive retail unit with display The business is being sold as a fully fitted out and equipped trading window onto Lendal and provides a retail area, food preparation unit, save as the commercial oven located within the food space, toilet facility and yard with walk-in cold store. preparation area. The business was opened in 2016 and has built a fantastic reputation SERVICES since, being well-known for supplying a range of high-quality pies, Mains water, 3-phase electricity and drainage are connected. pastries and pork products. The business has been run successively under full management and provides an excellent opportunity for an LOCAL AUTHORITY owner operator or established business to build upon that success. City of York Council. The trading name of the business is specifically excluded from the sale. -

UNIQUE FREEHOLD OPPORTUNITY for SALE Potential for Alternative Use Subject to Planning Shipton Road

22 LENDAL YORK, YO1 8DA UNIQUE FREEHOLD OPPORTUNITY FOR SALE Potential for alternative use subject to planning Shipton Road Wigginton Road Wigginton Malton Road Clifton Haxby Road Stockton Lane Burton Stone Lane Water End Penley’s Grove Street Hewarth Road DARLINGTON SCARBOROUGH A19 A1036 (A1M) RIVER FOSS (A64) Bootham St John St Gillygate Monkgate Tang Hall Lane Jewbury James Street Foss Bank Low Petergate Layerthorpe Foss Islands Road Melrosegate RIVER OUSE Stonegate Leeman Road 24 MILES TO Station Road LEEDS Fossgate Peasholme Green Piccadilly A1036 Navigation Road Castlegate HARROGATE Walmgate YORK RAILWAY Micklegate LOCATION Tower St STATION Skeldergate St Deny’s Road York is an internationally renowned tourist A59 destination and an attractive, historic A1036 cathedralA1079 city. It is located approximatelyHULL 1 HR & 50 MINS TO Hull Road Paragon Street LONDON VIA TRAIN Kent St 200 miles north of London, 24 miles Blossom Street Fishergate north-east of Leeds and 85 miles south Heslingtonof Newcastle. Road There are regular train A59 services to London that take under 1 hour and 50 minutes. Scarcroft Road LEEDS (A64) The retail market in York remains one A1036 of the strongest in the country. Latest research estimate 6.9 million visitors to VISITORS SPEND Barbican Road York per year, spending in the region of £564 million. York is home to a major £564 MILLION PER YEAR Albemarle Road university and benefits from a catchment A19 population of approximately 488,000 of Knavesmire Road Bishopthorpe Road which 294,000 regard York as their main shopping destination. York benefits from great variety with the prime trading areas of Coney Street, Davygate, High Ousegate and Parliament Street complementing the tourist streets of 6.9M VISITORS Stonegate, Low Petergate and The Shambles. -

The York (Station Avenue/ Lendal Bridge/Museum Street)

#TRO 385 BB BB/SN Updated 5 August 2013 THE YORK (STATION AVENUE/ LENDAL BRIDGE/MUSEUM STREET) (LOCAL BUS PRIORITY) (EXPERIMENTAL) TRAFFIC ORDER 2013 THE YORK (STATION AVENUE/LENDAL BRIDGE/MUSEUM STREET) (LOCAL BUS PRIORITY) (EXPERIMENTAL) TRAFFIC ORDER 2013 City of York Council, (the Council), in exercise of powers under Sections 9, 10 and Schedule 9 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 (the Act) and of all other enabling powers and after consultation with the Chief Officer of Police in accordance with Schedule 9 of the Act and being satisfied that for avoiding danger or the likelihood of danger arising to persons or other traffic using the roads to which this Order relates where access for a class of vehicle is prohibited for more than eight hours in twenty four it is requisite that Section 3(1)(b) of the Act should not apply to the Order, hereby makes the following Order: PART I - GENERAL CITATION 1. This Order may be cited as The York (Station Avenue/Lendal Bridge/Museum Street) (Local Bus Priority) (Experimental) Traffic Order 2013 and shall come into effect on the 27th day of August 2013 and expire on the 26th day of February 2015. INTERPRETATION 2. (1) (a) The Interpretation Act 1978 shall apply to this Order as it applies to an Act of Parliament. (b) Where a provision of this Order is in conflict with a provision contained in a previous order the provision of this Order shall prevail. (c) The headings and indices to this Order, other than those headings to the Schedules which are not enclosed in brackets, are included for reference only and do not form part of this Order.