Powers Inherent in Sovereignty: Indians, Aliens, Territories, and the Nineteenth Century Origins of Plenary Power Over Foreign Affairs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Front Matter

1_McKnight_FM_McKnight.qxd 7/10/13 12:13 PM Page vii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Contents Preface to the Paperback Edition ix Acknowledgments xvii Introduction 1 1 Assembling the “Official Truth” of Dallas 8 2 Creating the Warren Commission 30 3 Oswald in Mexico—Seven Days That Shook the Government 60 4 The Warren Commission Behind Closed Doors 89 5 The Warren Commission Confronts the Evidence 108 6 The Warren Commission’s “Smoking Guns” 128 7 The JFK Autopsy 153 8 Birth of the “Single-Bullet” Fabrication 181 9 Politics of the “Single-Bullet” Fabrication 213 10 FBI Blunders and Cover-Ups in the JFK Assassination 247 11 Senator Russell Dissents 282 12 Was Oswald a Government “Agent”? 298 13 JFK, Cuba, and the “Castro Problem” 330 Conclusion 354 Appendix A. FBI Damage Control Tickler 363 Appendix B. J. Lee Rankin’s Memorandum 366 Appendix C. A Brief Chronology and Summary of the Commission’s Case against Oswald 369 vii 1_McKnight_FM_McKnight.qxd 7/10/13 12:13 PM Page viii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. viii ContentsReproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Notes 373 Selected Bibliography 455 Index 463 A photograph section appears following page 236. 1_McKnight_FM_McKnight.qxd 7/10/13 12:13 PM Page ix © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Preface to the Paperback Edition Conspiracy is central to Breach of Trust—but it is not a conspiracy tale about who killed President Kennedy. -

RIPON For(.JM COMMENTARY

RIPON fOR(.JM COMMENTARY COMMENTARY The I rani:lII Crisis 2 Piercing the Myth of Soviel Superiority 4 Theodore Jacqucney 5 PR ES IDENTIAL SPOTLIGHT John Connally's Big Poli tical C:unble: A New U.S. Pol icy 6 for the Midd le East EDITORS NOTE 7 The The Palestinian Question and Iranian American Interests in the 8 Middle East Crisis A View From Amman 11 BOOK REVIEW Chea p Oil : How To Break 12 ew IIllernational events in the last three decades have OPEC seared the American psyche like the mass kidnapping Fof the American embassy staff by theocratic led mobs POLITICAL POTPOURRI 13 in Tehran. As we go 10 publication. this crisis remains 3t a fever pilch with the ultimate fate of the hostages still quite BUREAUCRACY uncerl3in. MARCHES ON 16 Yet not since the Japanese surpri se attack on Pearl ~la rbor has there been such a virtual unan imity of America n resolve to sta nd up 10 an adversary. Public reticence for direct U.S, intervention secrns linked almost exclusively to concern for KIPON fOK~M the safe return of the hostages. Should any harm befall Ihe hostages. the dovish position in Ame rican politics might be Ed itor: Arthul M. /l ill II to seizc Ayatollah Khomeini and his Revolutionary Council ElIccu\ivc Editor: Sleven D. ljl'cngood Art Director: Elizabeth Lee (The Graphic Tuna) for U.S. convened intern ational war crimes tribunals pur TilE RIPON FORUM (l5SN 0035-5526) is published month suant to the Nuremberg and Eichmann precedents. More in ly (except for the March/April and July/ August combined terventionist alternatives migh t range from U.S. -

Congressional Retraction of Federal Court Jurisdiction to Protect the Reserved Powers of the States: the Helms Prayer Bill and a Return to First Principles

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Villanova University School of Law: Digital Repository Volume 27 Issue 5 Article 7 1982 Congressional Retraction of Federal Court Jurisdiction to Protect the Reserved Powers of the States: The Helms Prayer Bill and a Return to First Principles James McClellan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Courts Commons Recommended Citation James McClellan, Congressional Retraction of Federal Court Jurisdiction to Protect the Reserved Powers of the States: The Helms Prayer Bill and a Return to First Principles, 27 Vill. L. Rev. 1019 (1982). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol27/iss5/7 This Symposia is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. McClellan: Congressional Retraction of Federal Court Jurisdiction to Protect 1981-82] CONGRESSIONAL RETRACTION OF FEDERAL COURT JURISDICTION TO PROTECT THE RESERVED POWERS OF THE STATES: THE HELMS PRAYER BILL AND A RETURN TO FIRST PRINCIPLES JAMES MCCLELLAN t S INCE THE EARLIEST DAYS OF THE WARREN COURT, countless bills have been introduced in Congress which would deny the federal courts jurisdiction over a great variety of subjects ranging from busing to abortion.' The exceptions clause of article III of the Constitution provides Congress with the authority to enact such bills. 2 While none of these proposed bills has been enacted into law, it is noteworthy that two have passed at least one house of Congress, and that both of these have sought to deny all federal courts, including the Supreme Court, jurisdiction over certain cases arising under the fourteenth amendment. -

Congressional. Record

. CONGRESSIONAL. RECORD. PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE FORTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS. SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE. SENATE. Maryland-Arthur P. Gorman and James B. Groome. Massachusetts-Henry L. Dawes and George F. Hoar. MoNDAY, October 10, 1881. Michigan-Omar D. Conger and Thomas W. Ferry. In Minnesota-Alonzo J. Edgerton and Samuel J. R. McMillan. pursuance of the proclamation of September 23, 1881, issued by Missi.sBippi-Jamea Z. George and Lucius Q. C. Lamar. President Arthur (James A. Garfield, the late President ofthe United M'us&uri-Francis M. Cockrell and George G. Vest. Sta.tes, having died on the 19th of September, and the powers and Nebraska-Alvin Saunders and Charles H. VanWyck. duties of the office having, in. conformity with the Constitution, de Nevada-John P. Jones. volved upon Vice-President Arthur) the Senate convened to-day in New Hampshire-Henry W. Blair and Edward H. Rollins. special session at the Capitol in the city of Washington. New Jersey-John R. McPherson and William J. Sewell. PRAYER. North Carolina-Matt. W. Ransom and Zebulon B. Vance. Rev. J. J. BULLOCK, D. D., Chaplain to the Senate, offered the fol Ohio-George H. Pendleton and John Sherman. lowing prayer : Oregon-La Fayette Grover and James H. Slater. Almighty God, our heavenly Father, in obedience to the call of the Pennsylvania-James Donald Cameron and John I. Mitchell. President of the United States, we have met together this day. We Rhode Island-Henry B. Anthony. meet under circumstances of the greatest solemnity, for since our last S&uth Carolina-M. -

Three Federalisms Randy E

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2007 Three Federalisms Randy E. Barnett Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/fwps_papers/23 This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/fwps_papers THREE FEDERALISMS RANDY E. BARNETT* ABSTRACT: Debates over the importance of “federalism” are often obscured by the fact that there are not one, but three distinct versions of constitutional federalism that have arisen since the Founding: Enumerated Powers Federalism in the Founding era, Fundamental Rights Federalism in the Reconstruction era, and Affirmative State Sovereignty Federalism in the post-New Deal era. In this very short essay, my objective is to reduce confusion about federalism by defining and identifying the origin of each of these different conceptions of federalism. I also suggest that, while Fundamental Rights Federalism significantly qualified Enumerated Powers Federalism, it was not until the New Deal’s expansion of federal power that Enumerated Powers Federalism was eviscerated altogether. To preserve some semblance of state discretionary power in the post-New Deal era, the Rehnquist Court developed an ahistorical Affirmative State Sovereignty Federalism that was both under- and over-inclusive of the role of federalism that is warranted by the original meaning of the Constitution as amended. In my remarks this morning, I want to explain how there are, not one, but three distinct versions of federalism that have developed since the Founding. -

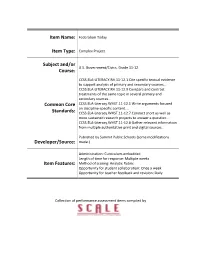

History SS Federalism Today Complex Project

Item Name: Federalism Today Item Type: Complex Project Subject and/or U.S. Government/Civics, Grade 11-12 Course: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources… CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.9 Compare and contrast treatments of the same topic in several primary and secondary sources… Common Core CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.1 Write arguments focused on discipline-specific content…. Standards: CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.7 Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects to answer a question… CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.8 Gather relevant information from multiple authoritative print and digital sources… Published by Summit Public Schools (some modifications Developer/Source: made.) Administration: Curriculum-embedded Length of time for response: Multiple weeks Item Features: Method of scoring: Analytic Rubric Opportunity for student collaboration: Once a week Opportunity for teacher feedback and revision: Daily Collection of performance assessment items compiled by Overview This learning module will prepare you to write an argument over which level of government, federal or state, should have the authority and power when making and executing laws on controversial issues. You will research an issue of your choice, write an argument in support of your position, and then present it to a panel of judges. Standards AP Standards: APS.SOC.9-12.I Constitutional Underpinnings of United States Government APS.SOC.9-12.I.D - Federalism Objective: Understand the implication(s) -

Federalism in the Constitution

Federalism in the Constitution As you read each paragraph, answer the questions in the margin. The United States is one country—but it’s also a bunch of states. You When creating the Constitution, what could almost say it’s a group of states that are, well, united. When we things did we need our central created the Articles of Confederation, each state already had its own government to be able to do? government and court system, so the new Americans weren’t exactly running amok. But if the new United States was going to be able to deal with other nations, it needed one government that would speak for the entire country. It also needed one central government to do things like declare war on other countries, keep a military, and negotiate treaties with other countries. There also needed to be federal courts where citizens from different states could resolve their disputes. So, the Founders created the Constitution to do those things. Define federalism. The United States Constitution created a central government known as the federal government. The federal government deals with issues that affect the entire country. Each state also has its own state government that only handles the affairs of that state. This division of power between a central government and state governments is called federalism. The federal government gets all of its power from the Create a Venn Diagram, with labels, that shows Constitution. These federal powers are listed in the the relationship between the federal powers, Constitution. In order to keep the federal government from reserve powers, and concurrent powers. -

Outline of United States Federal Indian Law and Policy

Outline of United States federal Indian law and policy The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to United States federal Indian law and policy: Federal Indian policy – establishes the relationship between the United States Government and the Indian Tribes within its borders. The Constitution gives the federal government primary responsibility for dealing with tribes. Law and U.S. public policy related to Native Americans have evolved continuously since the founding of the United States. David R. Wrone argues that the failure of the treaty system was because of the inability of an individualistic, democratic society to recognize group rights or the value of an organic, corporatist culture represented by the tribes.[1] U.S. Supreme Court cases List of United States Supreme Court cases involving Indian tribes Citizenship Adoption Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield, 490 U.S. 30 (1989) Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl, 530 U.S. _ (2013) Tribal Ex parte Joins, 191 U.S. 93 (1903) Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez, 436 U.S. 49 (1978) Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield, 490 U.S. 30 (1989) South Dakota v. Bourland, 508 U.S. 679 (1993) Civil rights Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191 (1978) United States v. Wheeler, 435 U.S. 313 (1978) Congressional authority Ex parte Joins, 191 U.S. 93 (1903) White Mountain Apache Tribe v. Bracker, 448 U.S. 136 (1980) California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians, 480 U.S. 202 (1987) South Dakota v. Bourland, 508 U.S. 679 (1993) United States v. -

Lloyd Bentsen Interview I

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION The LBJ Library Oral History Collection is composed primarily of interviews conducted for the Library by the University of Texas Oral History Project and the LBJ Library Oral History Project. In addition, some interviews were done for the Library under the auspices of the National Archives and the White House during the Johnson administration. Some of the Library's many oral history transcripts are available on the INTERNET. Individuals whose interviews appear on the INTERNET may have other interviews available on paper at the LBJ Library. Transcripts of oral history interviews may be consulted at the Library or lending copies may be borrowed by writing to the Interlibrary Loan Archivist, LBJ Library, 2313 Red River Street, Austin, Texas, 78705. LLOYD BENTSEN ORAL HISTORY, INTERVIEW I PREFERRED CITATION For Internet Copy: Transcript, Lloyd Bentsen Oral History Interview I, 6/18/75, by Michael L. Gillette, Internet Copy, LBJ Library. For Electronic Copy on Diskette from the LBJ Library: Transcript, Lloyd Bentsen Oral History Interview I, 6/18/75, by Michael L. Gillette, Electronic Copy, LBJ Library. GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS SERVICE Gift of Personal Statement By LLOYD BENTSEN to the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library In accordance with Section 507 of the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act of 1949, as amended. (44 U.S.C. 397) and regulations issued thereunder (41 CFR 101-10), I, Lloyd Bentsen, hereinafter referred to as the donor, hereby give, donate, and convey to the United States of America for deposit in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library, and for administration therein by the authorities thereof, a tape and a transcript of a personal statement approved by me and prepared for the purpose of deposit in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library. -

Challenge Bowl 2020

Notice: study guide will be updated after the December general election. Sponsored by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Challenge Bowl 2020 High School Study Guide Sponsored by the Challenge Bowl 2020 Muscogee (Creek) Nation Table of Contents A Struggle To Survive ................................................................................................................................ 3-4 1. Muscogee History ......................................................................................................... 5-30 2. Muscogee Forced Removal ........................................................................................... 31-50 3. Muscogee Customs & Traditions .................................................................................. 51-62 4. Branches of Government .............................................................................................. 63-76 5. Muscogee Royalty ........................................................................................................ 77-79 6. Muscogee (Creek) Nation Seal ...................................................................................... 80-81 7. Belvin Hill Scholarship .................................................................................................. 82-83 8. Wilbur Chebon Gouge Honors Team ............................................................................. 84-85 9. Chronicles of Oklahoma ............................................................................................... 86-97 10. Legends & Stories ...................................................................................................... -

Opening Brief of Intervenors-Appellants Elizabeth Trojan, David Delk, and Ron Buel

FILED July 12, 2019 04:42 AM Appellate Court Records IN THE SUPREME COURT THE STATE OF OREGON In the Matter of Validation Proceeding To Determine the Regularity and Legality of Multnomah County Home Rule Charter Section 11.60 and Implementing Ordinance No. 1243 Regulating Campaign Finance and Disclosure. MULTNOMAH COUNTY, Petitioner-Appellant, and ELIZABETH TROJAN, MOSES ROSS, JUAN CARLOS ORDONEZ, DAVID DELK, JAMES OFSINK, RON BUEL, SETH ALAN WOOLLEY, and JIM ROBISON, Intervenors-Appellants, and JASON KAFOURY, Intervenor, v. ALAN MEHRWEIN, PORTLAND BUSINESS ALLIANCE, PORTLAND METROPOLITAN ASSOCIATION OF REALTORS, and ASSOCIATED OREGON INDUSTRIES, Intervenors-Respondents Multnomah County Circuit Court No. 17CV18006 Court of Appeals No. A168205 Supreme Court No. S066445 OPENING BRIEF OF INTERVENORS-APPELLANTS ELIZABETH TROJAN, DAVID DELK, AND RON BUEL On Certi¡ ed Appeal from a Judgment of the Multnomah County Circuit Court, the Honorable Eric J. Bloch, Judge. caption continued on next page July 2019 LINDA K. WILLIAMS JENNY MADKOUR OSB No. 78425 OSB No. 982980 10266 S.W. Lancaster Road KATHERINE THOMAS Portland, OR 97219 OSB No. 124766 503-293-0399 voice Multnomah County Attorney s Office 855-280-0488 fax 501 SE Hawthorne Blvd., Suite 500 [email protected] Portland, OR 97214 503-988-3138 voice Attorney for Intervenors-Appellants [email protected] Elizabeth Trojan, David Delk, and [email protected] Ron Buel Attorneys for Petitioner-Appellant Multnomah County DANIEL W. MEEK OSB No. 79124 10949 S.W. 4th Avenue GREGORY A. CHAIMOV Portland, OR 97219 OSB No. 822180 503-293-9021 voice Davis Wright Tremaine LLP 855-280-0488 fax 1300 SW Fifth Avenue, Suite 2400 [email protected] Portland, OR 97201 503-778-5328 voice Attorney for Intervenors-Appellants [email protected] Moses Ross, Juan Carlos Ordonez, James Ofsink, Seth Alan Woolley, Attorney for Intervenors-Resondents and Jim Robison i TABLE OF CONTENTS I. -

Broadway East (Running North and South)

ROTATION OF DENVER STREETS (with Meaning) The following information was obtained and re-organized from the book; Denver Streets: Names, Numbers, Locations, Logic by Phil H. Goodstein This book includes additional information on how the grid came together. Please email [email protected] with any corrections/additions found. Copy: 12-29-2016 Running East & West from Broadway South Early businessman who homesteaded West of Broadway and South of University of Denver Institutes of Higher Learning First Avenue. 2000 ASBURY AVE. 50 ARCHER PL. 2100 EVANS AVE.` 2700 YALE AVE. 100 BAYAUD AVE. 2200 WARREN AVE. 2800 AMHERST AVE. 150 MAPLE AVE. 2300 ILIFF AVE. 2900 BATES AVE. 200 CEDAR AVE. 2400 WESLEY AVE. 3000 CORNELL AVE. 250 BYERS PL. 2500 HARVARD AVE. 3100 DARTMOUTH 300 ALAMEDA AVE. 2600 VASSAR AVE. 3200 EASTMAN AVE. 3300 FLOYD AVE. 3400 GIRARD AVE. Alameda Avenue marked the city 3500 HAMPDEN AVE. limit until the town of South 3600 JEFFERSON AVE. Denver was annexed in 3700 KENYON AVE. 1894. Many of the town’s east- 3800 LEHIGH AVE. west avenues were named after 3900 MANSFIELD AVE. American states and 4000 NASSAU AVE. territories, though without any 4100 OXFORD AVE. clear pattern. 4200 PRINCETON AVE. 350 NEVADA PL. 4300 QUINCY AVE. 400 DAKOTA AVE. 4400 RADCLIFF AVE. 450 ALASKA PL. 4500 STANFORD AVE. 500 VIRGINIA AVE. 4600 TUFTS AVE. 600 CENTER AVE. 4700 UNION AVE. 700 EXPOSITION AVE. 800 OHIO AVE. 900 KENTUCKY AVE As the city expanded southward some 1000 TENNESSEE AVE. of the alphabetical system 1100 MISSISSIPPI AVE. disappeared in favor 1200 ARIZONA AVE.