This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edinburgh PDF Map Citywide Website Small

EDINBURGH North One grid square on the map represents approximately Citywide 30 minutes walk. WATER R EAK B W R U R TE H O A A B W R R AK B A E O R B U H R N R U V O O B I T R E N A W A H R R N G Y E A T E S W W E D V A O DRI R HESP B BOUR S R E W A R U H U H S R N C E A ER R P R T O B S S S E SW E O W H U A R Y R E T P L A HE B A C D E To find out more To travel around Other maps SP ERU W S C Royal Forth K T R OS A E S D WA E OA E Y PORT OF LEITH R Yacht Club R E E R R B C O T H A S S ST N L W E T P R U E N while you are in the Edinburgh and go are available to N T E E T GRANTON S S V V A I E A E R H HARBOUR H C D W R E W A N E V ST H N A I city centre: further afield: download: R S BO AND U P R CH RO IP AD O E ROYAL YACHT BRITANNIA L R IMPERIAL DOCK R Gypsy Brae O A Recreation Ground NEWHAVEN D E HARBOUR D Debenhams A NUE TON ROAD N AVE AN A ONT R M PL RFR G PIE EL SI L ES ATE T R PLA V ER WES W S LOWE CE R KNO E R G O RAN S G T E 12 D W R ON D A A NEWHAVEN MAIN RO N AD STREET R Ocean R E TO RIN K RO IV O G N T IT BAN E SH Granton RA R Y TAR T NT O C R S Victoria Terminal S O A ES O E N D E Silverknowes Crescent VIE OCEAN DRIV C W W Primary School E Starbank A N Golf Course D Park B LIN R OSWALL R D IV DRI 12 OAD Park SA E RINE VE CENT 13 L Y A ES P A M N CR RIMR R O O V O RAN T SE BA NEWHAVEN A G E NK RO D AD R C ALE O Forthquarter Park R RNV PORT OF LEITH & A O CK WTH 14 ALBERT DOCK I HA THE SHORE G B P GRANTON H D A A I O LT A Come aboard a floating royal N R W N L O T O O B K D L A W T A O C O R residence or visit the dockside bars Scottish N R N T A N R E E R R Y R S SC I E A EST E D L G W N O R D T D O N N C D D and bistros; steeped in maritime S A L A T E A E I S I A A Government DRI Edinburgh College I A A M K W R L D T P E R R O D PA L O Y D history and strong local identity. -

North Vorthumberland

Midlothian Vice-county 83 Scarce, Rare & Extinct Vascular Plant Register Silene viscaria Vicia orobus (© Historic Scotland Ranger Service) (© B.E.H. Sumner) Barbara E.H. Sumner 2014 Rare Plant Register Midlothian Asplenium ceterach (© B.E.H. Sumner) The records for this Register have been selected from the databases held by the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. These records were made by botanists, most of whom were amateur and some of whom were professional, employed by government departments or undertaking environmental impact assessments. This publication is intended to be of assistance to conservation and planning organisations and authorities, district and local councils and interested members of the public. Acknowledgements My thanks go to all those who have contributed records over the years, and especially to Douglas R. McKean and the late Elizabeth P. Beattie, my predecessors as BSBI Recorders for Midlothian. Their contributions have been enormous, and Douglas continues to contribute enthusiastically as Recorder Emeritus. Thanks also to the determiners, especially those who specialise in difficult plant groups. I am indebted to David McCosh and George Ballantyne for advice and updates on Hieracium and Rubus fruticosus microspecies, respectively, and to Chris Metherell for determinations of Euphrasia species. Chris also gave guidelines and an initial template for the Register, which I have customised for Midlothian. Heather McHaffie, Phil Lusby, Malcolm Fraser, Caroline Peacock, Justin Maxwell and Max Coleman have given useful information on species recovery programmes. Claudia Ferguson-Smyth, Nick Stewart and Michael Wilcox have provided other information, much appreciated. Staff of the Library and Herbarium at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh have been most helpful, especially Graham Hardy, Leonie Paterson, Sally Rae and Adele Smith. -

410 Cumberland Avenue

CENTRAL PARK – WADDELL FOUNTAIN John Manuel, 1914 Waddell Fountain, the classic focal point of Central Park in downtown Winnipeg, is a legacy of one citizen's desire to be remembered and of the ornamental nature of the city's early greenspaces. As rapid growth transformed Winnipeg from a village to an urban centre, the need to reserve open spaces for aesthetic and recreational purposes became evident. In early 1893, City aldermen established a public parks board to create "ornamental squares or breathing spaces" (parks) and landscaped boulevards. Four park sites were acquired within a year, including a l.4 hectare block of land in the northern tip of the Hudson's Bay Company Reserve purchased from the company for $20,000 in cash and debentures. The property, bounded by Cumberland and Qu'Appelle avenues and Edmonton and Carlton streets, was undesirable for development due to poor drainage. Thousands of loads of soil © City of Winnipeg 1988 and manure were brought in to correct the problem and form a base for Central Park's lush lawns. This passive 'ornamental square' soon had walkways and gardens, followed in 1905 by a bandstand and two tennis courts. It also attracted nearby residential development. The Central Park/North Ellice area became a fashionable neighbourhood for professional and business families. The fountain was installed in 1914 to commemorate Emily Margaret Waddell who had come to Winnipeg in the early 1880s with her husband Thomas, a local temperance leader. It also symbolized the Scottish heritage of many early city residents as its design was based on a magnificent, 55-metre Gothic Revival monument to Sir Walter Scott, one of Scotland's best known romantic poets. -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

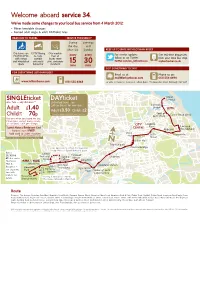

Welcome Aboard Service 34

Welcome aboard service 34. We’ve made some changes to your local bus service from 4 March 2012: • Minor timetable changes. • Revised adult single & adult DAYticket fares. REASONS TO TRAVEL SERVICE FREQUENCY During Evenings the day and Mon-Sat Sunday KEEP UP TO DATE WITH LOTHIAN BUSES Our buses are CCTV filming Our modern For service updates EASYACCESS to help fleet of every every Get real-time departures with ramps combat buses meet follow us on Twitter: from your local bus stop: and wheelchair anti-social strict emissions 15 30 twitter.com/on_lothianbuses mybustracker.co.uk space behaviour standards mins mins GOT SOMETHING TO SAY? FOR EVERYTHING LOTHIAN BUSES Email us at: Phone us on: [email protected] 0131 554 4494 www.lothianbuses.com 0131 555 6363 or write to Customer Services at Lothian Buses, 55 Annandale Street, Edinburgh EH7 4AZ Ocean Terminal Junction Bridge 1.40 3.50 LEITH Foot of Leith Walk Easter Road (foot) CITY Leopold CENTRE Place Lochend Abbeyhill Roundabout West Leith End Marionville Princes St Street Usher Hall Fountainpark Some buses run to or from the Royal Mail Fountainbridge Sorting Office at Sighthill Industrial Estate. Buses Sighthill 25, X25 & Parkhead Industrial Sighthill Terrace Shandon 45 also serve Estate Colleges Hermiston Longstone P&R & Hermiston Bankhead Slateford Station Riccarton – Research Sighthill Roundabout Terminus/ Inglis Green see separate Park Road Water of Leith Mains Rd Mains timetable Riccarton Burtons Visitor Centre leaflets for Riccarton Evening & Sunday buses run via details. (Heriot-Watt) -

1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate's Close Proximity to The

Edinburgh Graveyards Project: Documentary Survey For Canongate Kirkyard --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate’s close proximity to the Palace of Holyroodhouse, which is situated at the eastern end of Canongate Burgh, has been influential on both the fortunes of the Burgh and the establishment of Canongate Kirk. In 1687, King James VII declared that the Abbey Church of Holyroodhouse was to be used as the chapel for the re-established Order of the Thistle and for the performance of Catholic rites when the Royal Court was in residence at Holyrood. The nave of this chapel had been used by the Burgh of Canongate as a place of Protestant worship since the Reformation in the mid sixteenth century, but with the removal of access to the Abbey Church to practise their faith, the parishioners of Canongate were forced to find an alternative venue in which to worship. Fortunately, some 40 years before this edict by James VII, funds had been bequeathed to the inhabitants of Canongate to erect a church in the Burgh - and these funds had never been spent. This money was therefore used to build Canongate Kirk and a Kirkyard was laid out within its grounds shortly after building work commenced in 1688. 1 Development It has been ruminated whether interments may have occurred on this site before the construction of the Kirk or the landscaping of the Kirkyard2 as all burial rights within the church had been removed from the parishioners of the Canongate in the 1670s, when the Abbey Church had became the chapel of the King.3 The earliest known plan of the Kirkyard dates to 1765 (Figure 1), and depicts a rectilinear area on the northern side of Canongate burgh with arboreal planting 1 John Gifford et al., Edinburgh, The Buildings of Scotland: Pevsner Architectural Guides (London : Penguin, 1991). -

Lochs & Castles with a Local | Privately Guided Tours Scotland | 4

scotland.nordicvisitor.com SCOTTISH LOCHS & CASTLES WITH A LOCAL ITINERARY DAY 1 DAY 1: ARRIVAL IN EDINBURGH Upon your arrival in Edinburgh, you will be greeted by a private driver who will take you to your hotel in the city centre. For those arriving early in the day, we recommend spending the afternoon walking through the city, strolling along the Royal Mile and exploring the Old Town and New Town, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. There are also plenty of museums and landmarks to visit within the city centre, including the majestic Edinburgh Castle. Included: Entrance to Edinburgh Castle Spend the night in Edinburgh Attractions: Calton Hill, Edinburgh, Edinburgh Castle, Edinburgh New Town, Edinburgh Old Town, The Grassmarket, The Royal Mile & St Giles Cathedral DAY 2 DAY 2: WELCOME TO THE HIGHLANDS Today your guide will pick you up from your hotel in a comfortable vehicle to start your private tour. On the way you’ll have the option to go for a walk at the picturesque Hermitage and the Highland Folk Museum inside the Cairngorms National Park. Arriving near Inverness, you can visit the Battlefield of Culloden Moor, to see where the last battle on British soil occurred in 1746. Nearby you could also roam around Clava Cairns, a series of tombs and standing stones dating back roughly 4,000 years. Spend the night in Inverness area. Driving distance: 151 miles / 243 km Average travel & exploring duration: estimated 8-9 hours Attractions: Cairngorms National Park, Clava Cairns, Culloden Battlefield & Visitor Centre, Highland Folk Museum, Inverness, The Hermitage DAY 3 DAY 3: LOCH NESS, CASTLES & BRAVEHEART COUNTRY Today’s drive will take you back to Edinburgh (you also have the option to end your tour in Glasgow in the optional activities below), via Fort William and Braveheart Country. -

Post-Office Annual Directory

frt). i pee Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/postofficeannual182829edin n s^ 'v-y ^ ^ 9\ V i •.*>.' '^^ ii nun " ly Till [ lililiiilllliUli imnw r" J ifSixCtitx i\ii llatronase o( SIR DAVID WEDDERBURN, Bart. POSTMASTER-GENERAL FOR SCOTLAND. THE POST OFFICE ANNUAL DIRECTORY FOR 18^8-29; CONTAINING AN ALPHABETICAL LIST OF THE NOBILITY, GENTRY, MERCHANTS, AND OTHERS, WITH AN APPENDIX, AND A STREET DIRECTORY. TWENTY -THIRD PUBLICATION. EDINBURGH : ^.7- PRINTED FOR THE LETTER-CARRIERS OF THE GENERAL POST OFFICE. 1828. BALLAN'fVNK & CO. PRINTKBS. ALPHABETICAL LIST Mvtt% 0quaxt&> Pates, kt. IN EDINBURGH, WITH UEFERENCES TO THEIR SITUATION. Abbey-Hill, north of Holy- Baker's close, 58 Cowgate rood Palace BaUantine's close, 7 Grassmrt. Abercromby place, foot of Bangholm, Queensferry road Duke street Bangholm-bower, nearTrinity Adam square. South Bridge Bank street, Lawnmarket Adam street, Pleasance Bank street, north, Mound pi. Adam st. west, Roxburgh pi. to Bank street Advocate's close, 357 High st. Baron Grant's close, 13 Ne- Aird's close, 139 Grassmarket ther bow Ainslie place, Great Stuart st. Barringer's close, 91 High st. Aitcheson's close, 52 West port Bathgate's close, 94 Cowgate Albany street, foot of Duke st. Bathfield, Newhaven road Albynplace, w.end of Queen st Baxter's close, 469 Lawnmar- Alison's close, 34 Cowgate ket Alison's square. Potter row Baxter's pi. head of Leith walk Allan street, Stockbridge Beaumont place, head of Plea- Allan's close, 269 High street sance and Market street Bedford street, top of Dean st. -

Monumental Guidebooks 'In State Care' R W Munro*

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 115 (1985), 3-14 Monumental guidebooks 'in State care' R W Munro* SUMMARY A new series of guidebooks to Scottish monuments in State care is being produced by the Historic Buildings and Monuments Directorate of the Scottish Development Department. The origin and progress Government-sponsoredof guidebooks Scotlandin consideredare chiefly from pointthe of view of the non-expert user or casual visitor. INTRODUCTION Five years is not a long time in the history of an ancient monument, but in that period there has bee transformationa whicy b y h visitorwa e th n historii o st Governmencn i sitew sno t car helpee ear d to understand what they see. A new series of guidebooks and guide-leaflets is part of the continuing proces f improveo s d 'presentation' whic bees hha n carrie t ove yeare dou th r s successivelM H y yb Office of Works, the Ministry of Works (later of Public Building and Works), the Department of the Environment finallSecretare d th an , y yb Statf yo Scotlanr efo d acting throug Scottise hth h Develop- ment Department. One does not need to be particularly 'ancient' to have seen that rather bewildering procession of office, ministr departmend yan t pas rapin si d order acros bureaucratie sth c stage. Only since 197s 8ha the Scottish ful e Officlth responsibilitd eha y for wha bees tha n called 'our monumental heritagea '- useful blanket term which appears to cover the definitions of 'monument' and 'ancient monument' enshrined in the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act of 1979 (Maclvor & Fawcett 1983, 20). -

PASSAGES of MEDICAL HISTORY. Edinburgh Medicine, 1750-1800.*

PASSAGES OF MEDICAL HISTORY. Edinburgh Medicine, 1750-1800.* By JOHN D. COMRIE, M.A., B.Sc., M.D., F.R.C.P.Ed. In my ten-minute talk last May about the Edinburgh medical school I dealt with the founding of the Royal College of Physicians, the botanic garden, and the expansion of the Town's College into the University of Edinburgh through the establishment of a medical faculty in 1726. In the second half of the eighteenth century the medical school at Edinburgh became much more than a local institution, and not only attracted students from all over the British Isles, but was the chief centre to which men desiring to study medicine had recourse from the newly-founded British colonies through- out the world. Several of the teachers were men who attained great reputations. Dr Robert Whytt succeeded John Rutherford as professor both of the theory and practice of medicine in 1747, and was appointed largely because he was interested in medical research, a rare pursuit in those days. Stone in the bladder was a serious and frequent complaint which attracted great public interest and produced many reputed solvents for these calculi. Whytt had carried out an elaborate series of experiments in the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh with lime water, which he found to have a considerable power in disintegrating calculi, and he had published A n Essay on the Virtues of Lime Water and Soap in the Cure of the Stone. The treatment upon which he finally settled was to administer daily by the mouth water. He an ounce of soap and three pints or more of lime also published An Essay on the Vital and Other Involuntary Motions of Animals which brought him into conflict with the great Albrecht von Haller and gained him prominent notice on the Continent. -

Proceedings Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

PROCEEDINGS SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND. HUNDRED AND SECOND SESSION, 1881-82. ANNIVERSARY MEETING, SOtJi November 1881. PEOFBSSOS DUNS, D.D., Vice-President Chaire th n i ,. A Ballot having been taken, the following Gentlemen recom- mended by the Council were unanimously elected HONOKAKY FELLOW e Societth f So y :— Dr. LUDWIG LINDENSCHMIDT, Director of the Romisch-Gernianischen Central Museum, Maintz. Professor OLAF RYGH, Director of the National Museum of the Royal University, Christiania. Professor VIECHOW, Royal University, Berlin. Colonel HENRY YULE, Royal Engineers. The following Gentlemen were duly elected Fellows :— WILLIAM TBAQUAIH DICKSON, W.S. GEORGE GRAY, Solicitor, Glasgow. FREDERICK WALTER HADWEN, Kebroyd, Halifax. JAMES MAXTONE GHAHAME f Cultoc[uheyo , , Crieff. Rev. JAMES FORBES LEITH, Paris. VOL. xvr. A PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, NOVEMBER 30, 1881. KENNETH MACDONALD, Town Clerk of Inverness. HENRY COCKBURN MACANDREW, Sheriff Clerk of Inverness-shire. DAVID MACRITOHIE, C.A., Nort . AndrehSt w Street. Rev. JOHN OLIVER, Belhaven, Dunbar. Rev. ROBERT PAUL, F.C. Manse, Dollar. JOH . NREIDJ , Advocate, Queen' Lord san d Treasurer's Remembrancer in Exchequer for Scotland. ALEXANDER GEORGE REID, Solicitor, Auchterarder. Eev. W. ROBERTSON SMITH, 20 Duke Street. Office-Bearftre Th e ensuinth r fo s g year were electe follows da s :— President. THE MOST HON. THE MARQUESS OF LOTHIAN, K.T. ' Vice-Presidents. Rev. THOMAS MACLAUCHLAN, LL.D. R. W. COCHRAN-PATRICK, LL.D., M.P. The Right Hon. The EARL OF STAIR. Councillors. Sir J. NOEL PATON, Kt, LL.D., R.S.A., ^Representing the FRANCIS ABBOTT, ) Board f Trustees.o Professor NORMAN MACPHEHSON, LL.D. Captai . L.W THOMAS. -

Edinburgh's Urban Enlightenment and George IV

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Edinburgh’s Urban Enlightenment and George IV: Staging North Britain, 1752-1822 Student Dissertation How to cite: Pirrie, Robert (2019). Edinburgh’s Urban Enlightenment and George IV: Staging North Britain, 1752-1822. Student dissertation for The Open University module A826 MA History part 2. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2019 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Redacted Version of Record Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Edinburgh’s Urban Enlightenment and George IV: Staging North Britain, 1752-1822 Robert Pirrie LL.B (Hons) (Glasgow University) A dissertation submitted to The Open University for the degree of MA in History January 2019 WORD COUNT: 15,993 Robert Pirrie– A826 – Dissertation Abstract From 1752 until the visit of George IV in 1822, Edinburgh expanded and improved through planned urban development on classical principles. Historians have broadly endorsed accounts of the public spectacles and official functions of the king’s sojourn in the city as ersatz Highland pageantry projecting a national identity devoid of the Scottish Lowlands. This study asks if evidence supports an alternative interpretation locating the proceedings as epochal royal patronage within urban cultural history. Three largely discrete fields of historiography are examined: Peter Borsay’s seminal study of English provincial towns, 1660-1770; Edinburgh’s urban history, 1752-1822; and George IV’s 1822 visit.