PINTS, POLITICS and PIETY: the Architecture and Industries of Canongate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch

Art Appreciation Lecture Series 2015 Meet the Masters: Highlights from the Scottish National Gallery The Reverend Robert Walker skating on Duddingston Loch Angus Trumble 15/16 July 2015 Lecture summary: The Reverend Robert Walker skating on Duddingston Loch, c. 1798-1800, has not only become synonymous with the art of Sir Henry Raeburn, but has also assumed the character of an icon of the Scottish enlightenment, and of Scottish painting itself. Ten years ago, in a long article in the Burlington Magazine, Stephen Lloyd cast serious doubt upon the attribution to Raeburn on various grounds, and proposed instead that this action portrait was instead painted by the Frenchman Henri-Pierre Danloux. The ensuing controversy, and rebuttal, has shed much new light on the picture, and indeed the artist, but raises far broader questions as to the relationship between “technical” art history and connoisseurship. What are the limitations of each, and both in sometimes fraught dialogue? If, as is generally accepted, while iconic, The Reverend Robert Walker is a very unusual product of Raeburn’s studio, just how unusual can a picture be, at least in what used to be called an artist’s oeuvre, to raise and justify doubts as to its authorship? What factors, including a relatively secure provenance and close, not to say intense “looking,” may legitimately be marshalled in defence of the longstanding attribution to Raeburn? What is the role of scholarly consensus or, indeed, dissent in these debates? Slide list: 1. Henry Raeburn, The Reverend Robert Walker skating on Duddingston Loch, c. 1798-1800, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh (I shall return again and again to this image) 2. -

1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate's Close Proximity to The

Edinburgh Graveyards Project: Documentary Survey For Canongate Kirkyard --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate’s close proximity to the Palace of Holyroodhouse, which is situated at the eastern end of Canongate Burgh, has been influential on both the fortunes of the Burgh and the establishment of Canongate Kirk. In 1687, King James VII declared that the Abbey Church of Holyroodhouse was to be used as the chapel for the re-established Order of the Thistle and for the performance of Catholic rites when the Royal Court was in residence at Holyrood. The nave of this chapel had been used by the Burgh of Canongate as a place of Protestant worship since the Reformation in the mid sixteenth century, but with the removal of access to the Abbey Church to practise their faith, the parishioners of Canongate were forced to find an alternative venue in which to worship. Fortunately, some 40 years before this edict by James VII, funds had been bequeathed to the inhabitants of Canongate to erect a church in the Burgh - and these funds had never been spent. This money was therefore used to build Canongate Kirk and a Kirkyard was laid out within its grounds shortly after building work commenced in 1688. 1 Development It has been ruminated whether interments may have occurred on this site before the construction of the Kirk or the landscaping of the Kirkyard2 as all burial rights within the church had been removed from the parishioners of the Canongate in the 1670s, when the Abbey Church had became the chapel of the King.3 The earliest known plan of the Kirkyard dates to 1765 (Figure 1), and depicts a rectilinear area on the northern side of Canongate burgh with arboreal planting 1 John Gifford et al., Edinburgh, The Buildings of Scotland: Pevsner Architectural Guides (London : Penguin, 1991). -

The Register of Burials in the Churchyard of Restalrig 1728

lifelii p" I (SCOTTISH RECORD SOCIETY, INDEX TO THE REGISTER OF BURIALS IN THE CHURCHYARD OF RESTALRIG, 1728-1854. c EDITED BY FRANCIS J. GRANT, W.S., ROTHESAY HERALD AND LYON CLERK.- EDINBURGH : t) hos PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY BY JAMES SKINNER & COMPANY 1908. EDINBURGH: PRINTED BY JAMES SKINNER ANU COMPANY. 54- PREFACE. The village of Restalrig is situated in the parish of South Leith and on the eastern outskirts of the city of Edinburgh. It is a place of great antiquity, and in pre-Reformation times its collegiate church was the parish church of Leith. At the Reformation the church, which was dedicated to St. Triduana, was ordered by the General Assembly to be -razed and utterly cast down as a monument of idolatry, and the parishioners ordained to repair to St. Mary's Church at Leith, a sentence which was only too faithfully carried out. The edifice remained a ruin till the year 1836, when the present chapel of ease was constructed out of its remains. Though ceasing to be a place of worship after 1560, the churchyard continued to be a place of sepulchre, and after the disestablish- ment of Episcopacy in 1689 was used by the members of that body as a place of burial when denied the right to conduct service in other places. In 1726, with the sanction of John, Lord Balmerino, and James, Lord Coupar, his son, the proprietors of the Barony, the Friendly Society of Restalrig was constituted, and to its care the ruined church and church- yard were made over. The first members of this Society were Messrs. -

A Singular Solace: an Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000

A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 David William Dutton BA, MTh October 2020 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Stirling for the degree of Master of Philosophy in History. Division of History and Politics 1 Research Degree Thesis Submission Candidates should prepare their thesis in line with the code of practice. Candidates should complete and submit this form, along with a soft bound copy of their thesis for each examiner, to: Student Services Hub, 2A1 Cottrell Building, or to [email protected]. Candidate’s Full Name: DAVID WILLIAM DUTTON Student ID: 2644948 Thesis Word Count: 49,936 Maximum word limits include appendices but exclude footnotes and bibliographies. Please tick the appropriate box MPhil 50,000 words (approx. 150 pages) PhD 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by publication) 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by practice) 40,000 words (approx. 120 pages) Doctor of Applied Social Research 60,000 words (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Business Administration 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Education 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Midwifery / Nursing / Professional Health Studies 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Diplomacy 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Thesis Title: A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 Declaration I wish to submit the thesis detailed above in according with the University of Stirling research degree regulations. I declare that the thesis embodies the results of my own research and was composed by me. Where appropriate I have acknowledged the nature and extent of work carried out in collaboration with others included in the thesis. -

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook Illustrations of Edinburgh and other material collected by Sir Daniel Wilson, some of which he used in his Memorials of Edinburgh in the olden time (Edin., 1847). The following list gives possible sources for the items; some prints were published individually as well as appearing as part of larger works. References are also given to their use in Memorials. Quick-links within this list: Box I Box II Box III Abbreviations and notes Arnot: Hugo Arnot, The History of Edinburgh (1788). Bann. Club: Bannatyne Club. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated: W. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated in a series of views [ca. 1840]. Beauties of Scotland: R. Forsyth, The Beauties of Scotland (1805-8). Billings: R.W. Billings, The Baronial and ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland (1845-52). Black (1843): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1843). Black (1859): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1859). Edinburgh and Mid-Lothian (1838). Drawings by W.B. Scott, engraved by R. Scott. Some of the engravings are dated 1839. Edinburgh delineated (1832). Engravings by W.H. Lizars, mostly after drawings by J. Ewbank. They are in two series, each containing 25 numbered prints. See also Picturesque Views. Geikie, Etchings: Walter Geikie, Etchings illustrative of Scottish character and scenery, new edn [1842?]. Gibson, Select Views: Patrick Gibson, Select Views in Edinburgh (1818). Grose, Antiquities: Francis Grose, The Antiquities of Scotland (1797). Hearne, Antiquities: T. Hearne, Antiquities of Great Britain illustrated in views of monasteries, castles and churches now existing (1807). Heriot’s Hospital: Historical and descriptive account of George Heriot’s Hospital. With engravings by J. -

Kirkcudbright and Wigtown M R C Eet , the Iver Ree , with Its Estuary Broadening Into M Wigtown Bay , for S the Eastern Boundary of Wigtown

CA M B R I D G E UNIVE RSITY P RES S onhon FE ER LA NE E. C . Zfli : TT , 4 R C. CLA Y , M A NA G E m N ND L D o ba Qlalwtm an b M MI L LA A CO . T ‘ fi p, , fi ahm s : A C . < tific t : . M NT S N LT D . ran o J . D E O S , filokyo : M A R UZ E N - K A BUS H I KI - KA I S H A k qa ek KIRKC UD BRIG HT SHI RE A ND WIG T OWN SHIRE by WILLIA M kBA RM ONTH , G i - - r th o n P ub lic S ch o o l, G a teh o use o f Fleet With Ma s D a ams an d Illust atio n s p , i gr , r CA MBRID G E A T TH E UNI VE RSI T Y P RES S 1 9 2 0 CONTENTS P A G E S hi re O l Coun t a n d . y The rigin of Gal oway , k c d Wi town Kir u bright , g Gen eral Chara cteristics Si z e B d . Shape . oun aries Su rface a n d General Featu res R ivers a n d Lak es Geo logy Natural History Al on g th e Co ast h G a in s a n d o e B ea c es a . R aised . Coast l L ss s Lightho uses Clim ate e—R c c Peopl a e , Diale t , Population Agriculture M ct M e a n d M anufa ures , in s inerals Fish eries a n d d , Shipping Tra e Hi sto ry A n tiquities vi C ONTENTS — Architec ture (a ) Ecc lesiasti cal — Archi tecture (b) Milita ry — Archite cture (c) Dom esti c a n d Municipal Co m m uni catio n s Administration a n d Divisions Roll of Ho nour The Chi ef To wns a n d Vl lla ges ILLUST RAT IONS P A GE Glenlu ce Abbey o r ck o k o P tpatri , l o ing S uth R o ck s near Lo ch Enoch Lo ch Enoch a n d Merric k Head of Loch Troo l The Cree at Ma ch erm o re Ca rlin wa r k o c o g L h , Castle D uglas M d o o c Neldri ck en The ur er H le , L h On e o f B Tro o l the uchan Falls . -

Issue 7 Biography Dundee Inveramsay

The Best of 25 Years of the Scottish Review Issue 7 Biography Dundee Inveramsay Edited by Islay McLeod ICS Books To Kenneth Roy, founder of the Scottish Review, mentor and friend, and to all the other contributors who are no longer with us. First published by ICS Books 216 Liberator House Prestwick Airport Prestwick KA9 2PT © Institute of Contemporary Scotland 2021 Cover design: James Hutcheson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-8382831-6-2 Contents Biography 1 The greatest man in the world? William Morris Christopher Small (1996) 2 Kierkegaard at the ceilidh Iain Crichton Smith Derick Thomson (1998) 9 The long search for reality Tom Fleming Ian Mackenzie (1999) 14 Whisky and boiled eggs W S Graham Stewart Conn (1999) 19 Back to Blawearie James Leslie Mitchell (Lewis Grassic Gibbon) Jack Webster (2000) 23 Rescuing John Buchan R D Kernohan (2000) 30 Exercise of faith Eric Liddell Sally Magnusson (2002) 36 Rose like a lion Mick McGahey John McAllion (2002) 45 There was a man Tom Wright Sean Damer (2002) 50 Spellbinder Jessie Kesson Isobel Murray (2002) 54 A true polymath Robins Millar Barbara Millar (2008) 61 The man who lit Glasgow Henry Alexander Mavor Barbara Millar (2008) 70 Travelling woman Lizzie Higgins Barbara Millar (2008) 73 Rebel with a cause Mary -

Newsletter No.31

SBAA Newsletter No. 31 – April 2017 http://www.scottishbrewingarchive.co.uk/ web site [email protected] e-mail ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Welcome: Welcome to April’s Newsletter of the Scottish Brewing Archive Association. Please read it all. “View from the Chair” It would appear winter is over for another year, or so it would seem. To welcome the warmer weather, this month's SBAA Newsletter contains details of our events programme, so please take note of the dates for your diary. The first brewery visit is on the 16th May, so please contact promptly to book a place. Once again I would ask you to write in with your comments or any information you think would be of interest. It may be just your ideas. Be good to hear from you. John Martin Programme of SBAA Events: The following are the dates of visits and events planned during this year. If you wish to attend please contact John Martin by either phoning 0131 441 7718 or by e-mail [email protected] Numbers to be confirmed at least one week before the date. 16th May at 2:00pm Edinburgh Beer Factory The SBAA have been granted a 50% discount. Price of our visit is £7.50, which includes 2 drinks, a brewer-led tour, and a tutored tasting of unfiltered beer straight from the tank and a £5 voucher to spend in the gift shop. 15th June at 2:30om Broughton Brewery Dependent on numbers we may hire a mini-bus. 6th -8th July Scottish Real Ale Festival at the Corn Exchange in Edinburgh We normally staff a table to help promote the SBAA and need volunteers to help with this. -

The Edinburgh Graveyards Project

The Edinburgh Graveyards Project A scoping study to identify strategic priorities for the future care and enjoyment of five historic burial grounds in the heart of the Edinburgh World Heritage Site The Edinburgh Graveyards Project A scoping study to identify strategic priorities for the future care and enjoyment of ve historic burial grounds in the heart of the Edinburgh World Heritage Site Greyfriar’s Kirkyard, Monument No.22 George Foulis of Ravelston and Jonet Bannatyne (c.1633) Report Author DR SUSAN BUCKHAM Other Contributors THOMAS ASHLEY DR JONATHAN FOYLE KIRSTEN MCKEE DOROTHY MARSH ADAM WILKINSON Project Manager DAVID GUNDRY February 2013 1 Acknowledgements his project, and World Monuments Fund’s contribution to it, was made possi- ble as a result of a grant from The Paul Mellon Estate. This was supplemented Tby additional funding and gifts in kind from Edinburgh World Heritage Trust. The scoping study was led by Dr Susan Buckham of Kirkyard Consulting, a spe- cialist with over 15 years experience in graveyard research and conservation. Kirsten Carter McKee, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Architecture at Edinburgh University researching the cultural, political, and social signicance of Calton Hill, undertook the desktop survey and contributed to the Greyfriars exit poll data col- lection. Thomas Ashley, a doctoral candidate at Yale University, was awarded the Edinburgh Graveyard Scholarship 2011 by World Monuments Fund. This discrete project ran between July and September 2011 and was supervised by Kirsten Carter McKee. Special thanks also go to the community members and Kirk Session Elders who gave their time and knowledge so generously and to project volunteers David Fid- dimore, Bob Reinhardt and Tan Yuk Hong Ian. -

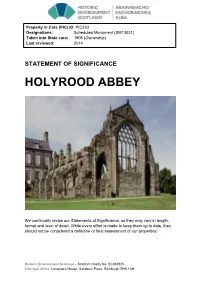

Holyrood Abbey Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC223 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13031) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HOLYROOD ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HOLYROOD ABBEY SYNOPSIS The Augustinian Abbey of Holyrood was founded by David I in 1128 as a daughter-house of Merton Priory (Surrey). By the 15th century the abbey was increasingly being used as a royal residence – James II was born there in 1430 - and by the time of the Protestant Reformation (1560) much of the monastic precinct had been subsumed into the embryonic Palace of Holyroodhouse. -

Open Space Audit 2016

Open Space Audit December 2016 Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Purpose of Audit 1 3 Audit Information and Classification 1 4 Audit Reference Tables (2016) 9 Public Parks and Gardens 9 Playspace 20 Residential Amenity greenspace 32 Green Corridor 53 Other Semi-natural Greenspace 66 Semi-natural Park 71 Playing Field 74 Bowling Green 78 Golf Course 82 Tennis Court 84 Churchyards 87 Cemeteries 88 Allotments 90 Civic Space 93 Summary (2016) 95 5 Audit Reference Tables (2009) Large Private Gardens and Grounds 96 Private Pleasure Gardens 97 Schools 99 Institutions 104 Business Amenity 106 Transport Amenity 107 Other Sports 108 Other Functional Greenspace - Other 109 Front cover: Leith Links Edinburgh Open Space Audit 1 Introduction 1.1 The Open Space Audit (2016) updates the Council’s first Open Space Audit, which was published in 2009. It classifies all significant open space within the urban areas of Edinburgh and its western settlements. It has been prepared by the Council in line with Scottish Planning Policy and Planning Advice Note (PAN) 65 and is updated every five years. 2 Purpose of Audit 2.1 The audit is an important step in preparing an open space strategy for the Council area. It provides basic information about the amount and quality of different types of open space. It makes it possible to set appropriate standards for quantity, quality and accessibility of open space, and to identify where these standards are being met and where they are not. Such an understanding allows priorities for change in open space to be chosen within a long-term, strategic context. -

Glimpse of Edinburgh & Beyond — 8 Days, 7 Nights

The Old Anchorage, Lochranza, Isle of Arran, Scotland “Our Britain - Your Choice” USA Cell Phone: 972 877 0082 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.britainbychoice.com Britain by Choice is your resource for travel in Scotland, England, Ireland Wales, northern France and Italy. With 25 years experience, programs have been developed over the years. We can also customize an itinerary to suit client’s special needs and interests. All itineraries are designed to ensure the minimum number of hotel changes. Glimpse of Edinburgh & Beyond — 8 days, 7 nights Commencing Daily from March to November Seasonal Pricing from $1445 (3 star) or $1745 (4 star) per person Tour #: S-8 HIGHLIGHTS 7 nights 3* or 4* accommodation 7 full Scottish Breakfasts 1 Scottish Evening & Banquet Round Trip Airport transfers 2 Walking Tours of old Edinburgh Scottish Heritage Pass 3 Full day Rabbies small group tours 2 day Royal Edinburgh Tour 1 day Forth Bridges and boat cruise tour Edinburgh Castle Day 1: Arrive Edinburgh International Airport for private transfer to either Attractions on “The Royal Mile” the 3 star Cairn Hotel or 4 star Mercure Princes St., for 7 nights, with a full Royal Mile Closes Scottish breakfast each morning. This afternoon (1:00pm) take the 2 hour Camera Obscura Mercat Tours Secrets of the Royal Mile walking tour of the western end of Tolbooth Kirk the Royal Mile. A 7 day Scottish Heritage Pass, providing expedited entry to Writers Museum over 130 major sites across across Scotlad is provided. Evening at leisure. Gladstones Land Day 2: Day 1 of the Royal Edinburgh Hop on Hop Off Tour, including entry to The Signet Library the Castle, Palace of Holyrood House and the Royal Yacht Britannia.