Panic and Persecution: Witch-Hunting in East Lothian, 1628-1631

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carment's Directory for Dalkeith And

ti i^^mtmi^ki ^1 o m h . PUBLICATION. § FIFTEENTH YEAR OF §\ \ .1 ^^^ l.^j GARMENT'S DIRECTORY hx §alkit| anb district, AND YEAR BOOK FOR •^ 1S9Q. *^ S'R.ICE-THIK.ElEI'lLllTCE. ,^9^^^^^^^:, DALKEITH. Founded 1805, The Oldest Scottish Insurance Office. GALEDONIAK INSURANCE COMPANY. INCOME, £628,674. FUNDS, £2,042,554, CLAIMS PAID EXCEED £5,500,000. LIFE ASSUEANCES AEE GRANTED WITH AND WITHOUT MEDICAL EXAMINATION ON VERY LIBERAL TERMS. Bonuses may le applied to make a whole-cf-life policy pay able diiriiig lifetime. Intermediate Bonuses are allowed. Perfect Non-forfeitable System. Policies in most cases unrestricted as regards Occupation and Foreign Residence or Travel. Claims payable 10 days after proof of death and title. FIRE DEPARTMENT. Security of the Highest Order. Moderate Premiums. Losses Promptly Settled. Surveys made J^ree of Charge. Head Office : 19 aEORGB STREET, EDINBURGH. Agents- IN Dalkeith— GEORGE JACK, S.S.C, Fairfield Place. JOHN GARMENT, 67 High Street. COLIN COCHRANE, Painter, 16 South Street. GEORGE PORTEOUS, 70 High Street ADVERTISEMENTS The Largest and Finest Selection of Music and Musical Instruments in the Kingdom. IMPORTANT. CHEAP AND GOOD PIANOS. THOROUGHLY GUARANTEED. An impression having got abroad that Paterson & Sons only deal in the Higher Class Pianos, they respectfully inform the Public that they keep always in Stock the Largest Selection in Town of the Cheaper Class of Good Sound Cottage Pianos, both New and Second H.and^ and their extensive deahngs with t^^e! • Che^^er Makers of the Best Class, eiiS^lgj;hg,isi|v^b, meet the Require- ments of all Mt^nding Bu^Vrs. -

Gypsy Traveller Site Handbook Old Dalkeith Colliery, Midlothian Welcome

Gypsy Traveller Site Handbook Old Dalkeith Colliery, Midlothian Welcome A 6 1 Welcome to Old Dalkeith Colliery Gypsy Traveller Site. 1 A A1 2 4 The site is situated on the boundary of East and Midlothian 1 near the village of Whitecraig. It is managed by East Lothian A Council. Whitecraig 0 Carberry 2 Your postal address is: 4 7 9 A 0 A6 6 Old Dalkeith A6 8 A 1 Pitch ____ Colliery 24 Old Dalkeith Colliery Dalkeith A 4 68 Midlothian 9 4 0 41 6 6 A EH22 2LZ A B 6 1 4 2 41 4 This handbook lets you know about the services that are B6 available on the site, your occupancy rights and Dalkeith A 6 responsibilities and gives you useful contact information. 8 1 Gypsy Traveller Site Handbook Site facilities Local facilities The site has 20 pitches and is open all year round. The nearest shop and post office are situated in Whitecraig. Please ask the Site Manager about the larger supermarkets Each pitch has: that are situated in Edinburgh, Musselburgh and Dalkeith. The nearest petrol station is situated at Granada Services (off • its own hard standing for parking a caravan and one other the A1 near Old Craighill Junction, by Musselburgh). motor vehicle • an amenity block with a toilet and shower/bath, kitchen area • a hook-up facility to provide electricity to your caravan. None of the pitches are currently adapted for use by people with disabilities. However, our Occupational Therapy service can provide advice and assistance with this. Please contact the Site Manager for further information. -

East Lothian

EAST LOTHIAN | BEAUTIFULLY CRAFTED 2, 3, 4, & 5 BEDROOM HOMES CUSTOMER NOTICE The plans, illustrations, photography, lifestyle images and dimen- sions (metric and imperial) included in this brochure are indica- tive. Computer generated images are from an imaginary viewpoint and are designed to portray the development characteristics rather than serve as an accurate description of properties. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of these details, we operate a policy of continuous product development and therefore individual features and specifications may vary at the discretion of Cruden Homes. We reserve the right to make adjustments to house types and consequently these particulars and the contents thereof do not form or constitute a representation warranty, or part of any contract. Welcome to a world of contrasts Introducing Longniddry Village – a brand-new development from multi award-winning Cruden Homes, in the heart of East Lothian. A gorgeous semi-rural setting with direct road and rail links into the heart of Edinburgh and featuring a unique blend of coach houses, bungalows and generous family villas, ranging in size from two to five bedrooms. Traditional and characterful architecture designed to the latest standards - whatever you’re looking for in your next dream home, you’ll find it here. Longniddry Village is a truly unique development and completely different from anything else currently available for sale in central Scotland. Its 71 homes acknowledge East Lothian’s rich variety of house styles, from coach houses to terraced, semi-detached and detached bungalows and villas. Here, Cruden Homes is creating a development which instantly feels part of this historic setting, with generous gardens and vehicle lanes ensuring welcoming streetscapes along each interconnected avenue. -

Carberry Hill a Hidden History Carberry Hill East Lothian

Queen Mary’s Mount A woodland walk, Visiting Carberry Hill East Lothian a hidden history Carberry Hill Roe deer Carberry Hill, once the home of the Elphinstone family is now owned and managed by the You can visit Carberry Hill all year round. Buccluech Estate. For more information, contact, Mr Cameron Manson, Head Ranger, The mature mixed woodlands are not just a Buccleuch Estates Ltd. great place for a walk, they are home to a host Dalkeith Estate, of birds and animals. Roe deer, foxes, magpies Dalkeith, and green woodpeckers can all be seen if you Midlothian, EH22 2NA. go quietly. You will also find amazing views over Tel: 0131 654 1666 Edinburgh, the Firth of Forth and much of Mid Email: [email protected] and East Lothian. Carberry Hill also has a special place in Scottish history. The woods ring with the echoes of our A woodland walk Celtic ancestors and the defeat of Mary Queen of Registered Charity: SCO181196 Scots. Work your way up the hill to the standing stone at the summit and learn more about why through this place is so special. danielbridge.co.uk, Manson, ELGT Cameron heather christie. Photogrpahy Wildife Design and location photography: history Walks around Carberry Hill Follow the signposts to enjoy a walk around this special place. Take time to look and listen for wildlife - you never know what you might see or hear. The paths can be muddy, so be sure to wear appropriate footwear. To Badger and blue tit Carberry Tower (refreshments) The commemorative stone at Queen Mary’s Mount Views to Edinburgh, East A6124 Lothian and the Carberry Firth of Forth Hill Queen Mary’s Mount Commemorative stone Views to East Lothian hill fort remains Red admiral B6414 Crossgatehall N Look for the E controversial claim 0 metres 50 100 150 200 250 made on the stone An aerial view W S 0 yards 50 100 150 200 250 by the hill fort of the hill fort. -

Architectural Heritage Trail Architectural Heritage Trail

1 Corn Exchange 4 Watch Tower Built in 1854 by public Built in 1827 subscription as the town’s to accommodate armed Corn Market, this was the watchmen looking out biggest indoor grain market for grave robbers. in Scotland. Map Map www.midlothianartist.wordpress.com Old Council Chambers 2 Former Cross Keys Hotel www.iwozheredalkeith.com 5 www.dalkeiththi.co.uk and Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop. Sculpture Edinburgh and Heritage Trail Heritage Heritage Trail Heritage and supported by Midlothian Council Council Midlothian by supported and reside reside residency was funded by Creative Scotland Scotland Creative by funded was residency e Architectural Architectural Architectural Architectural Built in 1882 and supported by Midlothian Training Services. Training Midlothian by supported and Midlothian Council and Historic Scotland Scotland Historic and Council Midlothian Dalkeith Business Renewal, Renewal, Business Dalkeith Heritage Lottery Fund, Fund, Lottery Heritage and extended in 1908 Dalkeith Heritage Dalkeith was funded by by funded was pupils of Kings Park Primary School, Dalkeith. School, Primary Park Kings of pupils as the headquarters of from Dalkeith History Society. Drawings were done by by done were Drawings Society. History Dalkeith from Midlothian Artist in Residence Susan T. Grant, with support support with Grant, T. Susan Residence in Artist Midlothian Conservation Area Regeneration Scheme (CARS) and and (CARS) Scheme Regeneration Area Conservation Dalkeith Town Council Dalkeith Townscape Heritage Initiative (THI), the Dalkeith Dalkeith the (THI), Initiative Heritage Townscape Dalkeith Dalkeith Heritage Dalkeith is a partnership between the the between partnership a is until 1975. here in 1827. in here water. public hanging was was hanging public 1 Cornof Exchangegallons 12,000 4 Watch Tower prison. -

A Singular Solace: an Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000

A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 David William Dutton BA, MTh October 2020 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Stirling for the degree of Master of Philosophy in History. Division of History and Politics 1 Research Degree Thesis Submission Candidates should prepare their thesis in line with the code of practice. Candidates should complete and submit this form, along with a soft bound copy of their thesis for each examiner, to: Student Services Hub, 2A1 Cottrell Building, or to [email protected]. Candidate’s Full Name: DAVID WILLIAM DUTTON Student ID: 2644948 Thesis Word Count: 49,936 Maximum word limits include appendices but exclude footnotes and bibliographies. Please tick the appropriate box MPhil 50,000 words (approx. 150 pages) PhD 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by publication) 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by practice) 40,000 words (approx. 120 pages) Doctor of Applied Social Research 60,000 words (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Business Administration 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Education 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Midwifery / Nursing / Professional Health Studies 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Diplomacy 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Thesis Title: A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 Declaration I wish to submit the thesis detailed above in according with the University of Stirling research degree regulations. I declare that the thesis embodies the results of my own research and was composed by me. Where appropriate I have acknowledged the nature and extent of work carried out in collaboration with others included in the thesis. -

East Lothian Council LIST of APPLICATIONS DECIDED by THE

East Lothian Council LIST OF APPLICATIONS DECIDED BY THE PLANNING AUTHORITY FOR PERIOD ENDING 29th May 2020 Part 1 App No 19/01171/P Officer: Mr David Taylor Tel: 0162082 7430 Applicant The Luxury Experience Company Limited Applicant’s Address Per Ross Hardie 10 Comrie Avenue Dunbar East Lothian EH42 1ZN Agent Agent’s Address Proposal Change of use of business premises (class 4) to office (class 2) and bar (sui generis) (Retrospective) Location 4 Brewery Lane Belhaven Dunbar East Lothian EH42 1PD Date Decided 29th May 2020 Decision Application Refused Council Ward Dunbar Community Council Dunbar Community Council App No 20/00141/P Officer: Ciaran Kiely Tel: 0162082 7995 Applicant Mr & Mrs Antony Hood Applicant’s Address Eelburn House 11 Westerdunes Park Abbotsford Road North Berwick East Lothian EH39 5HJ Agent LAB/04 Architects Agent’s Address Per Lee Johnson 17 Dean Park Longniddry East Lothian EH32 0QR Proposal Alterations, extensions to house, formation of hardstanding areas and installation of gate Location Eelburn House 11 Westerdunes Park North Berwick East Lothian EH39 5HJ Date Decided 29th May 2020 Decision Granted Permission Council Ward North Berwick Coastal Community Council North Berwick Community Council App No 20/00173/P Officer: Ciaran Kiely Tel: 0162082 7995 Applicant Ms E Nicol Applicant’s Address Venross Cottage Monktonhall Road Musselburgh EH21 6SA Agent Capital Draughting Cons Ltd Agent’s Address Per Keith Henderson 40 Dinmont Drive Edinburgh EH16 5RR Proposal Erection of 1 house and associated works Location Garden -

Hibernian Summer Football Camps 2018

HIBERNIAN SUMMER FOOTBALL CAMPS 2018 HIBERNIANCOMMUNITYFOUNDATION.ORG.UK TEL : 0131 656 7062 @HIBSINCOMMUNITY Welcome to the Hibernian Community Foundation’s Football Programme for Summer 2018. This booklet is packed with Hibee activities to make sure the Summer Holiday is active and full of football fun! Numbers are limited and are allocated on a first come–first served basis. 10% discount for siblings and for booking 3 or more weeks (please telephone book). Bookings can be taken over the phone on 0131 656 7062 or book online at www.hiberniancommunityfoundation.org.uk SUMMER AT A GLANCE… Week 1 : 2nd – 6th July : Hibernian Training Centre Camp Week 2 : 9th – 13th July : Hibernian Training Centre Camp Week 2 : 10th – 12th July : Galashiels Training Camp (NB : Tues to Thurs) Week 3 : 16th – 20th July : Advance Player Dev Camp at Hibernian Training Centre Week 3 : 16th – 20th July : North Berwick Training Camp Week 4 : 23rd – 27th July : Hibernian Training Centre Camp Week 4 : 23rd – 27th July : Goalkeepers Only Camp at Hibernian Training Centre Week 5 : 30th July – 3rd August : Girls Only Camp at Hibernian Training Centre Week 5 : 30th July – 3rd August : Hibernian Training Centre Camp Week 6 : 6th – 10th August: Hibernian Training Centre Camp @hibsincommunity @HibernianCommunityFoundation Week 1 : 2nd – 6th July Week 2 : 9th – 13th July Week 4 : 23rd – 27th July Week 5 : 30th July – 3rd August Week 6 : 6th – 10th August HTC CAMP East Mains, Ormiston, Tranent, EH35 5NG Our Hibernian Football Camps are designed for boys and girls of all ages (4-12yrs) and abilities. We aim to provide the highest quality age appropriate football coaching with the emphasis on fun and safety. -

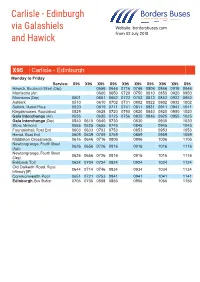

Carlisle - Edinburgh Via Galashiels Website: Bordersbuses.Com and Hawick from 02 July 2018

Carlisle - Edinburgh via Galashiels Website: bordersbuses.com and Hawick From 02 July 2018 X95 Carlisle - Edinburgh Monday to Friday Service: X95 X95 X95 X95 X95 X95 X95 X95 X95 X95 Hawick, Buccleuch Street (Dep) 0556 0646 0716 0746 0806 0846 0916 0946 Morrisons (Arr) 0600 0650 0720 0750 0810 0850 0920 0950 Morrisons (Dep) 0501 0601 0652 0722 0752 0812 0852 0922 0952 Ashkirk 0510 0610 0702 0731 0802 0822 0902 0932 1002 Selkirk, Market Place 0520 0619 0711 0741 0811 0831 0911 0941 1011 Kingsknowes, Roundabout 0529 0628 0720 0750 0820 0840 0920 0950 1020 Gala Interchange (Arr) 0535 0635 0725 0756 0825 0846 0925 0955 1025 Gala Interchange (Dep) 0540 0610 0640 0730 0830 0930 1030 Stow, Memorial 0555 0625 0655 0745 0845 0945 1045 Fountainhall, Road End 0603 0633 0703 0753 0853 0953 1053 Heriot, Road End 0609 0639 0709 0759 0859 0959 1059 Middleton Crossroads 0616 0646 0716 0806 0906 1006 1106 Newtongrange, Fourth Street 0626 0656 0726 0816 0916 1016 1116 (App) Newtongrange, Fourth Street 0626 0656 0726 0816 0916 1016 1116 (Dep) Eskbank Toll 0634 0704 0734 0824 0924 1024 1124 Old Dalkeith Road, Royal 0644 0714 0746 0834 0934 1034 1134 Infirmary [IF] Commonwealth Pool 0651 0721 0753 0841 0941 1041 1141 Edinburgh, Bus Station 0706 0736 0808 0856 0956 1056 1156 X95 Carlisle - Edinburgh Monday to Friday Service:Service: X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 X95X95 HawickCarlisle, Buccleuch, English St, Street The Courts(Dep) [A] 0855 05560955 0646 07161055 0746 08061155 0846 09161255 0946 MorrisonsKingstown (Arr) Road , -

3 Long Row Main Street, Tyninghame, Dunbar 3 Long Row, Main Street, Tyninghame, Dunbar, Eh42 1Xl

3 LONG ROW MAIN STREET, TYNINGHAME, DUNBAR 3 LONG ROW, MAIN STREET, TYNINGHAME, DUNBAR, EH42 1XL A delightful two bedroom cottage located in the picturesque conservation village of Tyninghame East Linton 1.5 miles ■ North Berwick 6 miles ■ Edinburgh 26 miles Acreage 0.11 acres (0.04 hectares) ■ Attractive country cottage with beautiful front and rear gardens ■ Oil-fired central heating ■ Within 3 miles of Tyninghame beach Edinburgh 0131 240 6960 [email protected] SITUATION 3 Long Row is situated in the heart of Tyninghame village, within East Lothian. Tyninghame provides a peaceful yet active village community with a coffee shop and numerous walking routes. The local towns of East Linton, North Berwick, Dunbar and Haddington are all within easy reach and provide a wide range of amenities. The A1 provides good road links both north and south and there are regular rail services to Edinburgh from North Berwick and Drem, and to London from Dunbar. DESCRIPTION This charming cottage has well-proportioned accommodation with two bedrooms. The front and rear gardens are highlights of the property with lawns and flowerbeds. The rear garden is equipped with a wooden shed. Internally, 3 Long Row has scope for modernisation offering the opportunity to add personal touches to suit the purchaser. The shower room has been recently refitted to provide an accessible wet room. ACCOMMODATION Ground Floor: Kitchen, Sitting Room, Master Bedroom, Bedroom 2 and Shower Room. SERVICES, COUNCIL TAX AND ENERGY PERFORMANCE CERTIFICATE Property Water Electricity Drainage Heating Council Tax EPC 3 Long Row Mains Mains Mains Oil Band C E POST CODE EH42 1XL WHAT3WORDS To find this property location to within 3 meters, download and use What3Words and enter the following 3 words: ///sung.implanted.recipient SOLICITORS Turcan Connell, Princes Exchange, 1 Earl Grey St, Edinburgh, EH3 9EE LOCAL AUTHORITY East Lothian Council, John Muir House, Brewery Park, Haddington, East Lothian, EH41 3HA FIXTURES AND FITTINGS No items are included unless specifically mentioned in these particulars. -

Hillview House 1C Main Street, Ormiston EH35 5HA an Attractive and Historic B-Listed Georgian House, Nestled in the Picturesque Village of Ormiston

HILLVIEW HOUSE 1C MAIN STREET, ORMISTON EH35 5HA An attractive and historic B-listed Georgian house, nestled in the picturesque village of Ormiston. GSB Properties 18 Hardgate Haddington EH41 3JS T: 01620 825368 F: 01620 824671 www.gsbproperties.co.uk PROPERTIES Property Hillview House is an attractive and historic B-listed high ceilings and original cornicing is still on display. Georgian house, nestled in the picturesque village Next door, an open plan kitchen, dining and family room of Ormiston. Restored and turned into two flats in awaits. This is the heart of the home and a door leads the 1980s, number 1C is a spacious main door and from here to the back garden. The property also offers ground floor flat, with mature gardens and a garage. 2 double bedrooms. The larger of the 2 has a walk-in The property offers period features and spaciousness wardrobe and a separate room which could be utilised associated with the Georgian era, with the added benefit as a large dressing area or even a study or home office. of being modernised. The large entrance vestibule with There are a further two small rooms just as you enter the original tiling makes a grand first impression. The sitting property, which could be used as a small library or extra room offers double aspect windows, including a large storage space. A bathroom with shower and disabled Ormiston bay window with lovely views over the gardens and the bath, completes the accommodation on offer. The attractive village of Ormiston is set amid the picturesque county of the East Lothian, known for its rolling countryside and rugged, breath-taking coastline. -

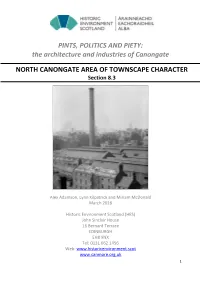

PINTS, POLITICS and PIETY: the Architecture and Industries of Canongate

PINTS, POLITICS AND PIETY: the architecture and industries of Canongate NORTH CANONGATE AREA OF TOWNSCAPE CHARACTER Section 8.3 Alex Adamson, Lynn Kilpatrick and Miriam McDonald March 2016 Historic Environment Scotland (HES) John Sinclair House 16 Bernard Terrace EDINBURGH EH8 9NX Tel: 0131 662 1456 Web: www.historicenvironment.scot www.canmore.org.uk 1 This document forms part of a larger report: Pints, Politics and Piety: the architecture and industries of Canongate. 8.3 NORTH CANONGATE AREA OF TOWNSCAPE CHARACTER Figure 214: Map showing boundary of North Canongate Area of Townscape Character © Copyright and database right 2016 Ordnance Survey licence number 100057073 For the purposes of this survey the North Canongate Area of Townscape Character lies to the north side of the Canongate backlands and is bounded by Cranston Street to the west, Calton Road and part of the railway track to the north and Campbell’s Close to the east. 8.3.1 Lost Sites on the Boundary with North Canongate Area The north side of Canongate was historically a focus for institutions to support its poorer and less fortunate residents. A number of charitable hospitals, poorhouses and correctional institutions were located in, or adjacent to, this part of Canongate burgh. Just outwith the north-western corner of this sector, where the railway line now marks the boundary of the survey area, were the earliest of these charitable institutions: Trinity Kirk and Hospital; and St Paul’s Work (shortened over time to Paul’s Work). These institutions stood on either side of Leith Wynd, a customs port on the edge of Edinburgh town, though not leading directly into the town itself.