Load Lines and Freeboard Marks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annexes to Riverdance Report No 18/2009

Annex 1 QinetiQ report on stability investigation of mv Riverdance COMMERCIAL IN CONFIDENCE MV RIVERDANCE Stability Investigation for MAIB August 2009 Copyright © QinetiQ ltd 2009 COMMERCIAL IN CONFIDENCE COMMERCIAL IN CONFIDENCE List of contents 1 Introduction 7 2 Investigation of the MV RIVERDANCE 8 2.1 MV RIVERDANCE Track 8 2.2 Environmental Conditions in the Area of the Incident 9 2.3 Loading Condition and Stability of MV RIVERDANCE 11 2.4 Stability Book Version 12 2.5 Evaluation of the Stability Book 12 2.6 Vessel loading condition 13 3 MV RIVERDANCE - Scenario Assessments 22 3.1 Prior to the incident 22 3.2 Dynamic Stability of MV RIVERDANCE in Stern Seas 22 3.3 The Turn to Starboard 27 3.4 Cargo Shift Prior to and After the Turn to Starboard 30 3.5 Wind Effects 37 3.6 Other potential contributing factors on the vessel angle following the turn 37 3.7 Combined List and Heel after turn - Cumulative effect of downflooding with cargo shift and wind effects 43 3.8 Potential Transfer of Fluid between Heeling Tanks (13) 47 3.9 The attempted re-floating of MV RIVERDANCE 58 3.10 The most likely sequence of events 59 4 Conclusions 63 4.1 Conclusions 63 5 References / Bibliography 66 6 Abbreviations 67 A Loading Conditions 68 A.1 Lightship 68 A.2 Estimated Load Condition 69 A.3 Plus 10% Cargo 70 A.4 Plus 15% Cargo 71 A.5 VCG Up 72 A.6 VCG Up plus 10% Cargo 73 A.7 VCG Up plus 15% Cargo 74 A.8 Cargo Shifted Up 75 A.9 Cargo Shifted Down 76 A.10 Tank states for all loading conditions 77 7 Initial distribution list 79 Page 4 COMMERCIAL IN CONFIDENCE COMMERCIAL IN CONFIDENCE List of Figures Figure 2-1 - MV RIVERDANCE track 9 Figure 2-2 - Water Depth 10 Figure 2-3 - Most likely cargo positioning 19 Figure 3-1- Parametric roll in regular head seas. -

Glossary of Nautical Terms: English – Japanese

Glossary of Nautical Terms: English – Japanese 2 Approved and Released by: Dal Bailey, DIR-IdC United States Coast Guard Auxiliary Interpreter Corps http://icdept.cgaux.org/ 6/29/2012 3 Index Glossary of Nautical Terms: English ‐ Japanese A…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...…..pages 4 ‐ 6 B……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……. pages 7 ‐ 18 C………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………...pages 19 ‐ 26 D……………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………………………..pages 27 ‐ 32 E……………………………………………………………………………………………….……………………….…………. pages 33 ‐ 35 F……………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………….………..……pages 36 ‐ 41 G……………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………...…………pages 42 ‐ 43 H……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….….………………..pages 49 ‐ 48 I…………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………….……….……... pages 49 ‐ 50 J…………………………….……..…………………………………………………………………………………………….………... page 51 K…………………………………………………………………………………………………….….…………..………………………page 52 L…………………………………………………………………………………………………..………………………….……..pages 53 ‐ 58 M…………………………………………………………………………………………….……………………………....….. pages 59 ‐ 62 N……………….........................................................................…………………………………..…….. pages 63 ‐ 64 O……………………………………..........................................................................…………….…….. pages 65 ‐ 67 P……………………….............................................................................................................. pages 68 ‐ 74 Q………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………………….……...…… page 75 R………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………………….………….. -

Container Crane Transport Options: Self-Propelled Ship Versus Towed Barge

Marine Heavy Transport & Lift 21-21 September 2005, London, UK CONTAINER CRANE TRANSPORT OPTIONS: SELF-PROPELLED SHIP VERSUS TOWED BARGE F. van Hoorn, Argonautics Marine Engineering, USA SUMMARY Container cranes are rarely assembled on the terminal quays anymore. These days, new cranes are delivered fully-erect, complete, and in operational condition. In today’s world economy, these fully-erect container cranes are routinely shipped across the oceans. New cranes are transported from manufacturers to terminals, typically on heavy-lift ships either owned by the manufacturer or by specialized shipping companies. Older cranes, often removed from the quay to make space for newer, bigger cranes, are relocated between ports and typically transported by cargo barges. Although the towed barge option is less expensive from a day rate point of view, additional expenses, such as the heavier seafastenings, higher cargo insurance premium, longer transit time, etc. need to be included in the cost trade-off analysis. Some recent container crane transports on ships and barges are discussed in detail and issues such as design criteria, stowage options, seafastening, etc. are addressed. Figure 1: Heavy-lift ship Swan departing Xiamen, China, with 2 new container cranes for delivery to Mundra, India 1. INTRODUCTION fully-erect container cranes are now routinely transported across the oceans. Most are new cranes, transported from New container cranes are on order for delivery to many their manufacturer to the ports of destination on heavy-lift ports around the world. With quay space a valuable ships either owned by the crane manufacturer or by commodity, the cranes are no longer assembled on the specialized shipping companies. -

Safety Analysis of EMCIP Data – Container Vessels

SAFETY ANALYSIS OF EMCIP DATA ANALYSIS OF MARINE CASUALTIES AND INCIDENTS INVOLVING CONTAINER VESSELS V1.0 September 2020 Safety analysis of EMCIP data – Container vessels Table of Contents 1. Executive summary ............................................................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Acknowledgement ....................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Disclaimer .................................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Why container vessels? .............................................................................................................................. 8 2.1.1 Overview of containership design features ........................................................................................ 10 2.1.2 Classification of Container Vessels .................................................................................................... 12 2.2 The EU framework for Accident Investigation ........................................................................................... 13 2.3 Finding potential safety issues through the analysis of EMCIP data ....................................................... -

Branch's Elements of Shipping/Alan E

‘I would strongly recommend this book to anyone who is interested in shipping or taking a course where shipping is an important element, for example, chartering and broking, maritime transport, exporting and importing, ship management, and international trade. Using an approach of simple analysis and pragmatism, the book provides clear explanations of the basic elements of ship operations and commercial, legal, economic, technical, managerial, logistical, and financial aspects of shipping.’ Dr Jiangang Fei, National Centre for Ports & Shipping, Australian Maritime College, University of Tasmania, Australia ‘Branch’s Elements of Shipping provides the reader with the best all-round examination of the many elements of the international shipping industry. This edition serves as a fitting tribute to Alan Branch and is an essential text for anyone with an interest in global shipping.’ David Adkins, Lecturer in International Procurement and Supply Chain Management, Plymouth Graduate School of Management, Plymouth University ‘Combining the traditional with the modern is as much a challenge as illuminating operations without getting lost in the fascination of the technical detail. This is particularly true for the world of shipping! Branch’s Elements of Shipping is an ongoing example for mastering these challenges. With its clear maritime focus it provides a very comprehensive knowledge base for relevant terms and details and it is a useful source of expertise for students and practitioners in the field.’ Günter Prockl, Associate Professor, Copenhagen Business School, Denmark This page intentionally left blank Branch’s Elements of Shipping Since it was first published in 1964, Elements of Shipping has become established as a market leader. -

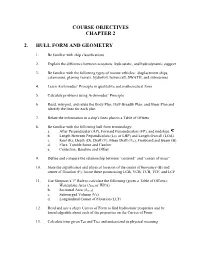

Course Objectives Chapter 2 2. Hull Form and Geometry

COURSE OBJECTIVES CHAPTER 2 2. HULL FORM AND GEOMETRY 1. Be familiar with ship classifications 2. Explain the difference between aerostatic, hydrostatic, and hydrodynamic support 3. Be familiar with the following types of marine vehicles: displacement ships, catamarans, planing vessels, hydrofoil, hovercraft, SWATH, and submarines 4. Learn Archimedes’ Principle in qualitative and mathematical form 5. Calculate problems using Archimedes’ Principle 6. Read, interpret, and relate the Body Plan, Half-Breadth Plan, and Sheer Plan and identify the lines for each plan 7. Relate the information in a ship's lines plan to a Table of Offsets 8. Be familiar with the following hull form terminology: a. After Perpendicular (AP), Forward Perpendiculars (FP), and midships, b. Length Between Perpendiculars (LPP or LBP) and Length Overall (LOA) c. Keel (K), Depth (D), Draft (T), Mean Draft (Tm), Freeboard and Beam (B) d. Flare, Tumble home and Camber e. Centerline, Baseline and Offset 9. Define and compare the relationship between “centroid” and “center of mass” 10. State the significance and physical location of the center of buoyancy (B) and center of flotation (F); locate these points using LCB, VCB, TCB, TCF, and LCF st 11. Use Simpson’s 1 Rule to calculate the following (given a Table of Offsets): a. Waterplane Area (Awp or WPA) b. Sectional Area (Asect) c. Submerged Volume (∇S) d. Longitudinal Center of Flotation (LCF) 12. Read and use a ship's Curves of Form to find hydrostatic properties and be knowledgeable about each of the properties on the Curves of Form 13. Calculate trim given Taft and Tfwd and understand its physical meaning i 2.1 Introduction to Ships and Naval Engineering Ships are the single most expensive product a nation produces for defense, commerce, research, or nearly any other function. -

Chapter 1A Pg 1

METRIC Instructional MANUAL CONTENTS Chapter Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Ship Draft, Trim and Stability Notes 14 3 Draft Survey 30 4 Cargo Deadweight 50 5 Trim and Stability 58 6 Grain Loading 73 7 Rolling Period Test for GM 88 Appendix 94 Draft and Stability Problems and Answers 94 - 1 - CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION PURPOSE 1.1 This Handbook is intended to assist Deck Officers with their loading calculations. Practical solutions are emphasised, and the most common questions about ship loading are answered. 1.2 More detailed knowledge may be obtained from published tomes on the subject which will provide fuller coverage of stability. DESCRIPTION 1.3 Chapter One, Introduction - describes the purpose of the Handbook. There is a summary of the contents of each chapter. An alphabetical listing of abbreviations used, a listing by chapter of formulas, and some recommended materials and equipment for performing ship-loading computations are also included. 1.4 Chapter Two, Ship Draft, Trim and Stability Notes -defines and discusses points and practices which have a practical effect on safe and economic ship loading. 1.5 Chapter Three, Draft Survey - describes in detail, complete with worked examples, the procedure for performing an International Standard Draft Survey. 1.6 Chapter Four, Cargo Deadweight - summarises the main considerations when performing cargo deadweight calculations. Each step in the procedure is then described in detail, complete with worked examples. 1.7 Chapter Five, Trim and stability - summarises the main considerations when performing trim and stability calculations. Each step in the procedures is then described in detail, complete with worked examples. -

SOLAS 2018 Consolidated Edition

SOLAS 2018 Consolidated Edition CHAPTER I GENERAL PROVISIONS PART A-APPLICATION, DEFINITIONS, ETC. Regulation 1 Application* * Refer to MSC-MEPC.5/Circ.8 on Unified interpretation of the application of regulations governed by the building contract date, the keel laying date and the delivery date for the requirements of the SOLAS and MARPOL Conventions. (a) Unless expressly provided otherwise, the present Regulations apply only to ships engaged on international voyages. (b) The classes of ships to which each Chapter applies are more precisely defined, and the extent of the application is shown, in each Chapter. Regulation 2 Definitions For the purpose of the present regulations, unless expressly provided otherwise: (a) Regulations means the regulations contained in the annex to the present Convention. (b) Administration means the Government of the State whose flag the ship is entitled to fly. (c) Approved means approved by the Administration. (d) International voyage means a voyage from a country to which the present Convention applies to a port outside such country, or conversely. (e) A passenger is every person other than: 1 (i) the master and the members of the crew or other persons employed or engaged in any capacity on board a ship on the business of that ship and (ii) a child under one year of age. (f) A passenger ship is a ship which carries more than twelve passengers. (g) A cargo ship is any ship which is not a passenger ship. (h) A tanker is a cargo ship constructed or adapted for the carriage in bulk of liquid cargoes of an inflammable* nature. -

Dangerous Solid Cargoes in Bulk

A selection of articles previously Dangerous solid published by Gard AS cargoes in bulk DRI, nickel and iron ores 3 Contents Carriage of dangerous cargo - Questions to ask before you say yes .............................................. 4 Understanding the different direct reduced iron products ................................................................ 7 Carriage of Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) by Sea - Changes to the IMO Code of Safe Practice for Solid Bulk Cargoes ....................................................................................................... 8 The dangers of carrying Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) .......................................................................... 11 Information required when offered a shipment of Iron fines that may contain DRI (C) ................ 12 Liquefaction of unprocessed mineral ores - Iron ore fines and nickel ore ...................................... 14 Intercargo publishes guide for the safe loading of nickel ore ......................................................... 18 Shifting solid bulk cargoes .................................................................................................................. 19 Cargo liquefaction - An update .......................................................................................................... 22 Cargo liquefaction problems – sinter feed from Brazil ..................................................................... 26 Liquefaction of cargoes of iron ore ................................................................................................... -

Ship Knowledge Questions

Ship Knowledge Questions PUBLISHED BY: All rights reserved. Great care has been taken with the DOKMAR Maritime Publishers BV No part of this publication may be investigation of prior copyright. In P.O.Box 5052 reproduced, stored in a retrieval case of omission the rightful CLaimant 4337RC Vlissingen, The Netherlands. system or transmitted in any form or is requested to inform the publishers. by any means, including electronic, © Copyright 2016, 9th edition mechanical, by photocopy, through Great care has been taken with the Dokmar, Vlissingen, recording or otherwise, without prior compilation of the text. However, mis- The Netherlands written permission of the publisher. takes may occur for which Dokmar accepts no responsibility. ISBN: 978-90-71500-32-9 QUESTIONS 1 For an easy, fun way to help you learn shipping rela- 1 ted terms, download "Ship Knowledge" from the Apple Appstore, or from Google Play and Start. 2 48. What is the sheer? 1 Principal dimensions 49. Why does the sheer in fore and aft ship give the vessel extra reserve buoyancy? 50. What is the camber? 51. What is the rise of floor? 1.1 Definitions 52. What is the bilge radius? 1. What is Length over all? 2. What means length between perpendiculars? 3. What means Loadline? 1.3 Proportions 4. What means Construction Waterline? 53. Name a number of ship's proportions related to the ratio of 5. What means 'moulded dimensions'? vessel main dimensions. 6. What is freeboard? 54. What is a usual L/B-ratio for a freighter? 7. What is a perpendicular? 55. Why is a small L/B-ratio unfavourable for the manoeuvrability? 8. -

Load Line Rules

RUSSIAN MARITIME REGISTER OF SHIPPING LOAFORD SEA-GOIN LINE GRULE SHIPS S Saint-Petersburg Edition 2017 Load Line Rules for Sea-Going Ships of Russian Maritime Register of Shipping have been approved in accordance with the established approval procedure and come into force on 1 January 2017. The present twentieth edition of the Rules is based on the nineteenth edition of 2016 taking into account the additions and amendments developed immediately before publication. The unified requirements, interpretations and recommendations of the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS) and the relevant resolutions of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) have been taken into consideration. The Rules are published in electronic format and hard copy in Russian and English. In case of discrepancies between the Russian and English versions, the Russian version shall prevail. ISBN 978-5-89331-352-9 © POCCHHCKHH MopcKofi peracTp CyHOXOflCTBa, 2017 As compared to the previous edition (2016), the twentieth edition contains the following amendments. LOAD LINE RULES FOR SEA-GOING SHIPS 1. Editorial amendments have been made. CONTENTS LOAD LINE RULES FOR SEA-GOING SHIPS 1 General 5 5 Special requirements for ships engaged in 1.1 Scope of application 5 international voyages which are assigned 1.2 Definitions and explanations 7 timber freeboards 43 1.3 Areas of navigation 10 5.1 Conditions of assignment of timber 1.4 Scope of survey and certificates 10 freeboards 43 1.5 General technical requirements 13 5.2 Calculation of minimum timber 2 Load line marking on ships engaged in freeboards 44 international voyages 14 6 Load lines of ships of 24 m in length and more 2.1 Deck line and load line mark 14 not engaged in international voyages 2.2 Lines to be used with load line mark. -

Extreme Waves and Ship Design

10th International Symposium on Practical Design of Ships and Other Floating Structures Houston, Texas, United States of America © 2007 American Bureau of Shipping Extreme Waves and Ship Design Craig B. Smith Dockside Consultants, Inc. Balboa, California, USA Abstract Introduction Recent research has demonstrated that extreme waves, Recent research by the European Community has waves with crest to trough heights of 20 to 30 meters, demonstrated that extreme waves—waves with crest to occur more frequently than previously thought. Also, trough heights of 20 to 30 meters—occur more over the past several decades, a surprising number of frequently than previously thought (MaxWave Project, large commercial vessels have been lost in incidents 2003). In addition, over the past several decades, a involving extreme waves. Many of the victims were surprising number of large commercial vessels have bulk carriers. Current design criteria generally consider been lost in incidents involving extreme waves. Many significant wave heights less than 11 meters (36 feet). of the victims were bulk carriers that broke up so Based on what is known today, this criterion is quickly that they sank before a distress message could inadequate and consideration should be given to be sent or the crew could be rescued. designing for significant wave heights of 20 meters (65 feet), meanwhile recognizing that waves 30 meters (98 There also have been a number of widely publicized feet) high are not out of the question. The dynamic force events where passenger liners encountered large waves of wave impacts should also be included in the (20 meters or higher) that caused damage, injured structural analysis of the vessel, hatch covers and other passengers and crew members, but did not lead to loss vulnerable areas (as opposed to relying on static or of the vessel.